|

Washington Stating the Reason for Jay's Nomination: Peace With Britain

Jay Treaty — November 19, 1794

Also: Jay's Treaty,

John Jay's Treaty, or Treaty of London

Formally:

Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation

|

|

This is the main article.

Go

here for the

transcript of

the Jay Treaty.

transcript of

the Jay Treaty.

And here for its official

appendix.

appendix.

|

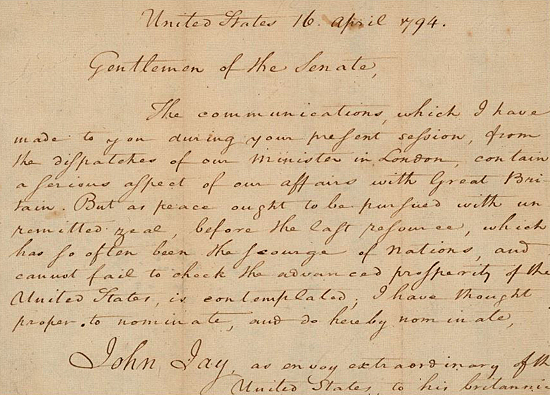

Image Above

President George

Washington's nomination of John Jay as Envoy

Extraordinary to his Britannic Majesty, April

16, 1794:

"But as peace

ought to

be pursued with unremitted* zeal [...] I have

thought proper to nominate John Jay, as envoy

extraordinary from the United States to his

Britannic majesty."

* unremitted =

without remission; incessant

Why Was the

Jay Treaty Negotiated in the First Place?

The United States wanted Great Britain to:

:: Evacuate British military

presence in the

Old Northwest, which

was officially U.S. territory since 1783.

Old Northwest, which

was officially U.S. territory since 1783.

:: Stop

impressment.

impressment.

:: Stop

the confiscation of American ships and their cargo.

::

Guarantee free international trade.

::

Return abducted slaves.

Great Britain wanted the United States to:

:: Allow British debt collectors

to go after pre-revolutionary debts.

::

Return confiscated property to their

pro-British (Loyalists, Americans who sided

with Great Britain during the war) owners.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Yes,

almost exactly the same issues had been

dealt with eleven years prior in

the

Treaty of Paris 1783.

Treaty of Paris 1783.

The more recent

grievances regarding international trade and

navigation stemmed from the war between France

and Britain, which commenced on February 1,

1793. (See

French Revolutionary Wars)

French Revolutionary Wars)

The U.S. was happy

to trade with both nations, but Britain targeted

neutral American ships that carried cargo to

France or French territories.

(See

British Order-in-Council

of June 8, 1793, and

British Order-in-Council

of June 8, 1793, and

November 6, 1793)

November 6, 1793)

What Was

Washington's Pickle?

On February 1, 1793, France

declared war on Great Britain and the United Provinces.

Check this event in the timeline of the French

Revolutionary Wars

Check this event in the timeline of the French

Revolutionary Wars

Pro-British Americans (such as Secretary of the Treasury

Alexander

Hamilton) and pro-French Americans (such as Secretary of State

Alexander

Hamilton) and pro-French Americans (such as Secretary of State

Thomas

Jefferson) urged Washington to take action according to

their respective political preferences.

Thomas

Jefferson) urged Washington to take action according to

their respective political preferences.

However, the United States was

officially neutral. Moreover, as a fledgling nation, the

United States' political and economic independence were

vulnerable, while its military was

still recuperating from the war.

officially neutral. Moreover, as a fledgling nation, the

United States' political and economic independence were

vulnerable, while its military was

still recuperating from the war.

Washington's objective was to continue business with both

Britain and France, while remaining impartial in foreign

politics.

To this end,

Washington sent a diplomat to Great Britain who was

pro-British and pro-peace: Chief Justice John Jay.

Was John Jay the Right Man for the Job?

John Jay was one of the

Founding

Fathers.

Alongside Hamilton and

Madison, he

wrote the

Federalist Papers

that promoted the ratification of the

Madison, he

wrote the

Federalist Papers

that promoted the ratification of the

Constitution.

Constitution.

Alongside

Adams and

Adams and

Franklin, Jay was part of the 1783

Paris peace committee. He negotiated and signed the

Franklin, Jay was part of the 1783

Paris peace committee. He negotiated and signed the

Treaty of Paris.

Treaty of Paris.

From 1784 to 1789 Jay was Secretary of Foreign Affairs

(today's Secretary of State.)

In 1789, Washington

made him the first chief justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Yet, Jay's nomination as special envoy was not unopposed.

On Saturday, April 19, 1794, the

U.S. Senate considered the motion,

That

any communications to be made to the Court

of Great Britain may be made through our

Minister now at that Court, with equal

facility and effect, and at much less

expense... and that such an appointment is

at present inexpedient and unnecessary.

That to

permit Judges of the Supreme Court to hold

at the same time any other office or

employment, emanating from and holden at the

pleasure of the Executive, is contrary to

the spirit of the Constitution, and, as

tending to expose them to the influence of

the Executive, is mischievous and impolite.

After this motion passed in the

negative with 10 Yeas and 17 Nays, Senate voted to

agree to Jay's nomination with 18 Yeas and 8 Nays.

Who Signed the

Jay Treaty?

Chief Justice

of the Supreme Court

John Jay

for

the United States

under  President George

Washington

President George

Washington

and

Foreign

Secretary

William Wyndham

Grenville, Lord Grenville

for Great Britain

under King George

III

When Was the

Treaty

Signed and Ratified?

Jay and Grenville signed at

London on November 19, 1794.

The United States ratified the treaty on

August 14, 1795.

Great Britain ratified the

treaty on October 28, 1795.

Ratifications were exchanged at

London on October 28, 1795.

Why the

Delay Between Signing and Ratifying?

The treaty was signed at London and arrived on Edmund Randolph's (Secretary of State) desk in

Philadelphia at 7 p.m. on March 7, 1795. At this time, the

U.S. Senate was not in session.

Why the Senate?

The U.S. Constitution gives the

president power to make treaties if two-thirds of the Senate

agree. In addition, the Senate may amend a treaty or adopt

changes to a treaty.

The Constitution reads,

He shall have

Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of

the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two

thirds of the Senators present concur;

The Senate convened on June 8,

1795, and deliberated for two weeks.

On June 24, 1795, it passed the following resolution of ratification by a vote of 20 to 10,

meaning it just passed with the required two-thirds

majority:

Resolved, two-thirds of the Senate

concurring therein, that they do consent to,

and advise the President of the United

States, to ratify the treaty of amity,

commerce, and navigation, between his

Britannic Majesty and the United States of

America, concluded at London, the 19th day

of November, 1794, on condition that there

be added to the said treaty an article,

whereby it shall be agreed to suspend the

operation of so much of the 12th article, as

respects the trade which his said Majesty

thereby consents may be carried on, between

the United States and his islands in the

West Indies, in the manner, and on the terms

and conditions therein specified.

And the Senate recommend to the President to

proceed, without delay, to further friendly

negotiations with his Majesty, on the

subject of the said trade, and of the terms

and conditions in question.

Washington simply pinned this

Additional Article to

the treaty, and ratified it on

August 14, 1795.

Additional Article to

the treaty, and ratified it on

August 14, 1795.

Did Britain Have

a Problem With the Additional Article?

No. The U.S. ratified

treaty arrived in London

in October 1795. From London,

John Quincy Adams

reported on November 14, 1795:

John Quincy Adams

reported on November 14, 1795:

The additional Article, suspending the clause in the twelfth

article according to the ratification of the Senate, was

agreed to without difficulty.

What Was Agreed

Upon in the Jay Treaty?

|

:: |

Britain will have withdrawn all its troops from

U.S. soil by June 1, 1796.

|

|

:: |

Free trade between British and U.S.

territories in North America

|

|

:: |

A

joint survey of the upper Mississippi

River, followed by amicable

negotiations

|

|

:: |

The

Treaty of

Paris made the St.

Croix River part of the mutual

border. Commissioners will decide

which river that is.

Treaty of

Paris made the St.

Croix River part of the mutual

border. Commissioners will decide

which river that is.

|

|

:: |

The U.S. will compensate British

creditors for losses occasioned by legal

impediments to the collection of debts

contracted prior to 1783.

Commissioners will ascertain how much the U.S.

will have to pay.

|

|

:: |

Maritime claims:

Great Britain will compensate American citizens for illegal captures of their

vessels by British subjects.

The U.S. will compensate British

citizens for illegal captures of

their vessels or merchandize within

their their jurisdiction or by vessels

armed in their ports.

Commissioners will ascertain the

payable amounts.

|

|

:: |

Free trade between British

territories in Europe and the U.S.

|

|

:: |

Limited trade between British

territories in the East Indies and the U.S.

|

|

:: |

Regulations on privateering as well

as on how to proceed when vessels

are captured on suspicion of having

enemy's property or contraband

goods.

|

|

:: |

Subjects or citizens of one party

shall not accept commission from a

foreign state at war with the other.

|

What Did

Washington Think of the Jay Treaty?

George Washington

to Secretary of State, Edmund Randolph, July 22,

1795:

My opinion respecting the treaty, is

the same now that it was: namely, not

favorable to it, but that it is better to

ratify it in the manner the Senate have

advised (and with the reservation already

mentioned), than to suffer matters to remain

as they are, unsettled.

Implementation

and Debate About Treaty Power

On February 29, 1796, President

Washington proclaimed the Jay Treaty in effect.

On March 1, 1796,

he forwarded it to Congress for legislative

implementation.

In other words,

implementing the treaty required money, and according to the U.S.

Constitution, Section 9,

No

Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but

in Consequence of Appropriations made by

Law;

Thus, the House of Representatives began debate on the appropriation bill

on March 2, 1796.

At least that was

the plan. The Constitution

was brand-new, and nearly no precedence at all

could be referred to, so the debate immediately

shifted towards the extend of treaty power.

If the House

has to decide whether to accept or reject an appropriation

bill, shouldn't the House be authorized to

review instructions presented to the

negotiator and other relevant papers and

notes?

If treaties

are considered "law," wouldn't it follow

that the House is required to pass their appropriation bills,

and that it would be actually against the

law not to do so?

How can the

president conduct meaningful negotiations if

there's a chance that the House will refuse

the allocation of funds necessary for a

treaty's execution?

These were the

Debates in the House of Representatives of the

United States, During the First Session of the

Fourth Congress Upon the Constitutional Powers

of the House with Repect to Treaties (Philadelphia: Printed for

Benj. Franklin Bache by Bioren & Madan,

1796), which have been made accessible online by multiple

sources.

Finally, the debate shifted back to the

appropriation bill at hand, and on April 30,

1796, it passed by a whisker, with a vote of 51 to 48.

Was the Jay

Treaty Good or Bad for the U.S.?

Although the Jay Treaty was wildly

unpopular, it achieved Washington's main objective — it calmed Anglo-American

relations.

At least for now. For the next

clash see the

War of 1812.

War of 1812.

But in the meantime, the

U.S. economy benefited enormously from the continued

peace with Britain.

In Donald R. Hickey's The War

of 1812, he points out that the Jay Treaty ...

... allowed

American commerce — and hence the American

economy — to flourish. American exports,

which stood at $33 million in 1794, soared

to $94 million in 1801, and the entire

nation basked in the resulting prosperity.

But was that enough?

Impressment, for example, was

not addressed by the treaty, and became a major issue within

a decade.

(See

Impressment, for example, was

not addressed by the treaty, and became a major issue within

a decade.

(See  Why Was the War of 1812 Fought?)

Why Was the War of 1812 Fought?)

And the French, of course, were completely

miffed.

After having signed a military as well

as a commercial treaty with the U.S. in 1778, and helping the Americans

win their Revolution, the Jay Treaty was more than a slap in

the French face.

Consequently, the French

confiscated American merchant ships, which caused financial

loss in the millions, and the undeclared

Quasi War

was fought from 1798 to 1800.

Quasi War

was fought from 1798 to 1800.

Controversy: Why Didn't Jay Come Home With a

Better Treaty?

So, why wasn't John Jay able to

negotiate a stronger treaty, a treaty more favorable to the

United States?

Two reasons:

One, Britain was at war with

revolutionary France, which not only threatened an invasion,

but also to radically turn traditional British values

upside down. Britain, therefore, had bigger worries than

maintaining amicable ties with the U.S., a rather

weak military power at the time. In other words, the

United States wanted something from Britain, not the other

way round, which made for a weak bargaining position.

Two, pro-British Secretary of the Treasury Alexander

Hamilton assured British Minister to the United

States, George Hammond, that the

United States would not join European powers in an armed

neutrality against Britain. Hamilton's angle? Trade with Britain

takes priority over friendly connections with France. This

meddling effectively rendered one of Jay's "or else" arguments moot.

All things considered, the

U.S. came out with a pretty good treaty.

Arguing against the above is:

One, while it is true that

Britain had bigger worries, it certainly wasn't keen on

adding yet another enemy. Britain would have been interested in an amicable

treaty with the U.S.

Two, the U.S. joining the

European armed neutrality was not really a concern of

the British, whose maritime power was superior and far from

exhausted. The U.S. navy was weak, and joining the European

armed neutrality would have been a logistical nightmare for

the States.

So far the Jay Treaty controversy.

How was the Jay Treaty received

in the States?

Outrage

Back in the U.S., pro-French citizens and

politicians were scandalized alike. Francophile Jefferson called

the Jay Treaty "a

millstone round our necks."

And speaking of necks...

In his book Presidential

Courage - Brave Leaders and How They Changed America,

Michael R. Beschloss notes,

The

protest was spreading. When Hamilton

defended Jay's Treaty in front of New York's

City Hall, people threw rocks, leaving his

face bloody. [...] In Boston Harbor, mobs

set a British ship aflame.

In Philadelphia, they cried, "Kick this

damned treaty to hell!"

Spearing a copy of Jay's pact with a sharp

pole, the revelers marched it to Minister

Hammond's house, burned it on his doorstep

and broke his windows, with Hammond and his

family cowering inside.

Thomas

Jefferson had not seen the American "public

pulse beat so full" on "any subject since

the Declaration of Independence."

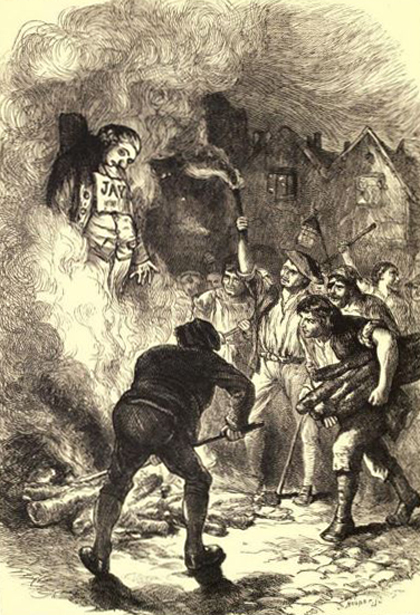

Furthermore, in several

cities, public frustration was communicated by burning effigies of John Jay.

Burning Jay's Effigy

Cassell's

History of the United States by Edmund Ollier

Vol. II, Cassell, Petter & Galpin

Was all this outrage justified?

On October 5,

1795, John Quincy Adams wrote that,

The

treatment of Mr. Jay is certainly such as

does no honor to the American name.

It

appears to me evident enough, that very

little of the outcry of which the treaty is

made the pretence is meant to bear against

that instrument.

There

is a combination of personal envy of the

man, of factious enmity against the

government, and of eternal foreign influence

operating unseen, all assuming the mark of

pure and exalted patriotism, to impose upon

the people; that the mask should be assumed

is neither new nor strange; but that it

should still answer its purpose would be

surprising, if any thing could surprise.

Arbitration

The three Jay Treaty Commissions

marked the birth of modern international arbitration.

The St. Croix River Commission

(Article V) was a success. On October 25, 1798, it

proclaimed the northern branch of the Schoodiac River as the

official border. By doing so, the commissioners not only

ended years of bickering with a final decision, but also

with a compromise. Which might or might not have been their

job. But it sure solved the issue.

This commission had three

commissioners: Thomas Barclay for Britain, David Howell for

the U.S., and Egbert Benson.

The British Debts Commission

(Article VI) was a fiasco due to the fact that the fifth

commissioner voted 100% pro-Britain. On January 8, 1802,

Great Britain

and the United States annulled Article VI of the Jay Treaty, and

Britain accepted a lump sum of £600,000.

This commission had five

commissioners: Thomas Macdonald and Henry Pye Rich for

Britain, Thomas Fitzsimons and James Innes (died and

replaced by Samuel Sitgreaves) for the U.S., and John

Guillemard.

The Maritime Commission

(Articles VII and VIII) was a success. They were done on

February 24, 1804, having awarded American claimants a total

of $11,650,000, and British claimants a total of

$143,428.14.

This commission had five

commissioners: John Nicholl and John Antsey for Britain,

Christopher Gore and William Pinkney for the U.S., and John

Trumbull.

Read more in Richard B. Lillich's

The Jay Treaty Commissions.

The Jay Treaty Commissions.

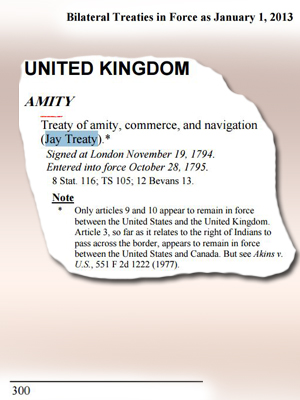

Is the Jay

Treaty Still in Force?

Yes, it is. At least part of it.

Here is a peek into

A List of Treaties and

Other International

Agreements of the

United States in Force

on January 1, 2013, provided by the United States Department of State.

This publication lists treaties and other international

agreements of the United States on record in the

Department of State on January 1, 2013, which had not

expired by their own terms or which had not been

denounced by the parties, replaced, superseded by other

agreements, or otherwise definitely terminated.

The Note reads: "Only articles 9 and 10 appear to remain in force

between the United States and the United

Kingdom. Article 3, so far as it relates to the

right of Indians to pass across the border,

appears to remain in force between the United

States and Canada."

And here you can check

all treaties currently in force**.

all treaties currently in force**.

** (archived content 2010)

Jay Treaty

Trivia

::

Original Copy

The Department of

State does not have a signed original of the Jay Treaty in

its archives.

Washington sent

Britain a ratified original, but at the exchange

of ratifications, Britain gave back their

ratification on a lousy copy. See more in

Hunter Miller's Notes

from Avalon.

Hunter Miller's Notes

from Avalon.

:: Additional Article

The date of the additional article

is not May 4, 1796.

The additional

article was recited textually in each

instrument of ratification, but was not

otherwise drawn up or signed; in 8 Statutes

at Large, 130, the date thereof is given

erroneously as May 4, 1796.

Again, more from the same

Hunter Miller.

Hunter Miller.

Maps

1783-1803

United States

1792 Europe

More History

|