|

Explorers, Scientists &

Inventors

Explorers, Scientists &

Inventors

Musicians, Painters &

Artists

Musicians, Painters &

Artists

Poets, Writers &

Philosophers

Poets, Writers &

Philosophers

Native Americans & The Wild

West

Native Americans & The Wild

West

First Ladies

First Ladies

Popes

Popes

Troublemakers

Troublemakers

Historians

Historians

Archaeologists

Archaeologists

Royal Families

Royal Families

Tribes & Peoples

Tribes & Peoples

Assassinations in History

Who

got slain, almost slain, when, how,

why, and by whom?

Go to the

Assassination Archive

Go to the

Assassination Archive

Online History Dictionary A - Z

All-Time Records in

History

What was the

bloodiest battle, the battle with the least

casualties, who was the greatest military leader?

Go to

Records in History

Go to

Records in History

The Divine Almanac

Who all roamed the heavens in

olden times? The Who's Who of

ancient gods.

Check out

the Divine Almanac

Check out

the Divine Almanac

French Revolution Glossary A-Z

::

Ancien Régime

Ancien régime is French for Old Rule,

also translated as Old Order, and refers

to the government, the political and social

order of France before the Revolution.

:: Calendar

or rather French

Republican Calendar

The French Republican Calendar was the official

timetable of the French from September 22, 1792,

until December 31, 1805.

For the French

revolutionary soul, the Gregorian Calendar, the

one we are using today, reminded too much of

religion.

On October 5,

1793, the

National Convention

decided to use the Republican Calendar instead

of the Gregorian Calendar.

National Convention

decided to use the Republican Calendar instead

of the Gregorian Calendar.

On that day, the

Republican Calendar was put in place

retroactively. The first day of the first year

of this calendar was the date of the

proclamation of the Republic — September 22,

1792.

September 22,

1792, was 1 Vendémiaire, year I.

Weeks were

replaced by décades of ten days. Each of

the twelve months had exactly 30 days, or 3

décades.

At the end of the

360 days, five public holidays were added and a

sixth day every fourth year, to celebrate the

sanculottide.

The 12 months of

the Republican Calendar were poetically named

with reference to agriculture and climate:

Vendémiaire

(vintage)

September 22 to October 21

Brumaire

(mist)

October 22 to November 20

Frimaire

(frost)

November 21 to December 20

Nivôse (snow)

December 21 to January 19

Pluviôse

(rain)

January 20 to February 18

Ventôse (wind)

February 19 to March 20

Germinal

(seedtime)

March 21 to April 19

Floréal

(blossom)

April 20 to May 19

Prairial

(meadow)

May 20 to June 18

Messidor

(harvest)

June 19 to July 18

Thermidor

(heat)

July 19 to August 17

Fructidor

(fruits)

August 18 to September 16

Here is an excellent French Republican

Calendar Converter put up by Stephen P.

Morse:

Go to

Stephen's French

Calendar converter

Stephen's French

Calendar converter

::

Committee

of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety was established

on April 6, 1793. There were 9, and later

12, members of this committee, who were to be re-elected

each month.

The National

Convention thought it would be a good idea to set up

this committee in order to be able to more

effectively coordinate measures against foreign

and domestic threats.

First president of

the Committee was

Georges

Danton, who was a

moderate. Too moderate, people thought, and in

July 1793, he was replaced by Georges

Danton, who was a

moderate. Too moderate, people thought, and in

July 1793, he was replaced by

Robespierre and

other men of Robespierre's caliber.

Robespierre and

other men of Robespierre's caliber.

Power thus

centralized in the hands of a few

radicals, the Committee became bigger than

its creator and introduced the Reign of Terror. Georges Danton himself ended up on

the guillotine in April 1794.

The power and

importance of the Committee of Public Safety

faded after Robespierre's execution in July

1794.

However, it still

had power over matters regarding foreign affairs

and war. In March 1796, for example, the

Committee decided to make Napoleon commander of

the army of Italy.

::

Consulate

The Consulate was the French government from

1799 to 1804.

Officially, three consuls ( Napoleon,

Napoleon,

Emmanuel-Joseph

Sieyès, and Emmanuel-Joseph

Sieyès, and  Pierre-Roger Ducos) were in power.

Unofficially, Napoleon was the only one in

charge. Pierre-Roger Ducos) were in power.

Unofficially, Napoleon was the only one in

charge.

In 1804, Napoleon

decided to drop the pretense and declared

himself emperor.

:: Corvée

The unpaid labor that you owed to your lord

(seigniorial corvée) or to your king

(royal corvée) if you were a vassal.

The word derives

from Latin corrogata opera, which means

requested work.

A French peasant

who lived in the year 800 was obliged to work

180 days per year for free for his lord.

In time, free

labor for a lord was replaced by a tax.

Louis XIV

brought back a royal corvée for road and

highway constructions.

Louis XIV

brought back a royal corvée for road and

highway constructions.

In 1787,

Louis XVI

decided that the royal corvée had to be

paid in form of a tax, which was added to your

regular tax, the taille.

Louis XVI

decided that the royal corvée had to be

paid in form of a tax, which was added to your

regular tax, the taille.

In 1789, the

Constituent Assembly

abolished the corvée.

Constituent Assembly

abolished the corvée.

Today, spoiled

French teenagers still complain about corvée

when told to clean up their rooms. But only the

educated ones.

::

Directory

The Directory (French: Directoire) was

the French government from November 1795 to

November 1799. It had been created by the

National Convention, which prepared its

constitutional foundation. National Convention, which prepared its

constitutional foundation.

The Directory had

two chambers: The lower house, also called the

Council of Five Hundred, or

Conseil de Cinq-Cents,

with 500 delegates, and the Council of Elders,

or Conseil des Anciens, with 250

delegates.

The 500 were to

suggest laws, the 250 were to approve them.

Executive authority was in the hands of five

directors, elected by both chambers. These

directors were Barras,

Rewbell,

Lareveillère,

Letourneur,

and  Carnot.

Carnot.

The Directory was

a complete disaster because it was corrupt and

had no teeth, i.e. it could not implement or

enforce its own decisions.

On September 4,

1797, the Directory had royalists and other

undesired individuals not only banned from the

administration but also deported, just to be

sure. This was the

Coup of

18 Fructidor, year V. Executive

in charge was General

Augereau.

Napoleon was

behind the coup that ended the Directory on

November 9-10, 1799, also called the

Coup

of 18-19 Brumaire, year VIII.

The  Consulate became the new government of

France.

Consulate became the new government of

France.

The Conseil des

Cinq-Cents existed from October 27, 1795 -

December 26, 1799.

::

Émigrés

French aristocrats who emigrated because of the

French Revolution and who tried to re-establish

their power from abroad. French nobles in exile.

::

Estates-General

Also called the States

General (French: États-Généraux

or simply États), this was an assembly of

deputies from the three estates, also called the

three orders:

the clergy

(First Estate)

the nobility

(Second Estate)

the commons

(Third Estate)

The Estates-General existed under the French

monarchy and met more or less regularly to

discuss matters of public interest. Their powers

were advisory only.

The

Estates-General assembled for the first time on

April 10, 1302, prompted by French

King Philip IV the Fair

who needed support in his struggle with

Pope Boniface VIII.

The

Estates-General assembled for the last time on

May 5, 1789,

at Versailles.

May 5, 1789,

at Versailles.

Technically, they

met once more on July 9, 1789, only to confirm

the creation of the

National Assembly

(Assemblée Nationale), that had been proclaimed on

June 17, 1789.

::

Ferme Générale

The Ferme Générale, or General Tax

Farm, was an organization

that collected indirect taxes for the King.

The lease for the

royal permission to collect was awarded every

six years.

The Ferme Générale

employed its tax collectors, the

fermiers-généraux, or farmers-general.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert

created the Ferme Générale in 1681. It

was abolished in 1791.

::

Gabelle

The gabelle, or gabela, was a tax

on salt established back in 1341 under

Philip VI of Valois.

By 1789, the salt

tax had become a ridiculously unequal tax in

France.

Here is a map:

Map Gabelle France 1789

The gabelle

was abolished in 1790.

Here is

more about the

gabelle.

more about the

gabelle.

:: Girondists

A Girondist, or Girondin, was a member of the

moderate republican party of France from 1791 to

1793. Their policy was also referred to as

Girondism.

It's leaders were

the deputies from Gironde, a department located

in southwestern France. See map

Gironde

Department, France 1790

:: Jacobins

A Jacobin was a member of the radical Jacobin

Club, the most famous political group of the

French Revolution, associated with extreme views

and violence. The Jacobins led the French

Revolutionary government from mid-1793 to

mid-1794. Their goal was absolute equality.

The Jacobins

started out calling themselves the Society of

the Friends of the Constitution (from 1789

to 1792) and then switched to become the

Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Liberty and

Equality (from 1792 to 1794.)

The name Jacobins

derives from their club house, a former convent

of the Dominicans, who built it near the church

of Saint Jacques (Saint Jacobus or Saint James)

in Paris.

One of the Jacobin

leaders was

Maximilien

de Robespierre. Another famous

member of the Jacobins was Maximilien

de Robespierre. Another famous

member of the Jacobins was

Napoleon. Napoleon.

In the National

Convention, the Jacobins were known as the

Montagnards.

:: La Plaine (The Plain)

La Plaine were those deputies in the National

Convention who were seated on the floor and

had the majority. Members of La Plaine were mostly moderate.

At first, La

Plaine voted with the Girondins, but later, when it

came to Louis XVI's execution, with the

Montagnards. In the end, they acted against the

Montagnards and against the Committee of Public

Safety.

::

Lettre de Cachet

Cachet is the French word for stamp

or seal.

By means of a

lettre de cachet, a letter with the royal

seal and co-signed by a secretary of state, the

King could summon anyone anywhere willy-nilly.

Some of these

letters put individuals into prison without

trial or hearing (see

Bastille),

some summoned political bodies of people to

assemble or to appear before His Royal Highness. Bastille),

some summoned political bodies of people to

assemble or to appear before His Royal Highness.

The lettres de

cachet appeared in the mid-sixteenth century

and were used, at first, exceptionally. Later,

their usage grew proportionally to the usage of

royal absolutism.

Originally, the

King issued these letters because he felt like

doing so. Later, more and more individuals sent

applications for such a letter.

As a police

officer in Paris you could apply for lettres

de cachet to keep your streets crime free,

the advantage being a, if not necessarily just

but speedy incarceration process. In the 18th

century, lieutenants of the police have been

using these lettres more than 60,000

times.

Families could

seek a lettre de cachet for their

"libertine son", "unfaithful husband",

"promiscuous wife", or simply "insane uncle"

etc.

Under

King Louis XV,

who ruled 1715-1774, the lettre de cachet

was in demand like it had never been before. A

massive amount of ministers was required to go

through these applications and to approve or

deny them.

King Louis XV,

who ruled 1715-1774, the lettre de cachet

was in demand like it had never been before. A

massive amount of ministers was required to go

through these applications and to approve or

deny them.

Criticism grew,

accusing the monarchy of targeting innocent

victims of private vendettas and family feuds.

The arbitrary use of the lettres de cachet

became a symbol of intolerable absolutism.

The

Constituent Assembly

abolished the lettre de cachet in 1790,

carefully seeing to it that a good number of

those imprisoned at the time would stay where

they were.

Constituent Assembly

abolished the lettre de cachet in 1790,

carefully seeing to it that a good number of

those imprisoned at the time would stay where

they were.

::

Montagnards

A Montagnard (French for Mountain Man)

was a Jacobin in the National Convention, and so

called because they were seated on the higher

benches at the convention.

::

National Assembly

The National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale)

grew out of the

Estates-General,

a solely advisory council to the King.

Estates-General,

a solely advisory council to the King.

The National

Assembly was established by the Third Estate on

June

17, 1789, and became the first French

revolutionary parliament. June

17, 1789, and became the first French

revolutionary parliament.

It existed from

June 17 to

July 9, 1789,

when its legitimacy was confirmed by the First

and the Second Estate, and it was renamed

National Constituent

Assembly.

July 9, 1789,

when its legitimacy was confirmed by the First

and the Second Estate, and it was renamed

National Constituent

Assembly.

The National

Constituent Assembly was active until September

30, 1791. On October 1, 1791, the

Legislative Assembly,

became its successor.

National Assembly — Achievements:

Abolition of

feudal privileges

August 4, 1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

August 26, 1789

Nationalization of Church property

November 2, 1789

Civil Constitution

of the Clergy

July 12, 1790

Prohibition of

strikes and workers' unions

Le Chapelier Law, June 14, 1791

Constitution

of 1791

Accepted by the King on September 14, 1791

Penal Code

Penal Code

September 25, 1791

And here is a list of the

presidents of the National

Assembly 1789-1791.

presidents of the National

Assembly 1789-1791.

::

National Convention

The French National Convention (Convention

Nationale) was the government of France from

September 21, 1792 until October 26, 1795.

The National

Convention replaced the Legislative Assembly (Assemblée

Législative,) which had been in session from

October 1, 1791, to September 21, 1792.

This assembly, the

National Convention,

consisted of 749 elected deputies. They met for

the first time on September 21, 1792, and

immediately abolished the monarchy. The very

next day they established the French Republic.

Altogether, the

National Convention issued 15,414 decrees.

National Convention — Timeline & Factions:

- From September 1792 to May 1793, the National

Convention was overshadowed by the power struggle

between the

Montagnards and the Montagnards and the

Girondins. Girondins.

- The Girondins

lost and the Montagnards controlled the National

Convention from June 1793. They set up the

Committee of Public Safety, which dominated the

National Convention until July 1794. Committee of Public Safety, which dominated the

National Convention until July 1794.

- The

Reign of

Terror ruled from September 5, 1793, to July 27,

1794, during which a suspect had no rights

whatsoever and people were executed by the

bunch.

Reign of

Terror ruled from September 5, 1793, to July 27,

1794, during which a suspect had no rights

whatsoever and people were executed by the

bunch.

- The Committee

became too radical for many moderate members of

the National Convention from the center, also

called The Plain (La Plaine) and was

toppled by them. This was the

Revolution

of 9 Thermidor, year II, or July

27, 1794.

After the overthrow of the

Committee, the Girondins were recalled to the

convention.

The National

Convention was replaced by the

Directory in

November 1795.

Directory in

November 1795.

::

Parlement

A judicative, administrative, and political

institution in France during the Middle Ages and

under the

ancien régime.

ancien régime.

Not to be confused with the English

parliament. (nervous chuckle)

The parlements

represented the nation while the  Estates General

was not in session.

Estates General

was not in session.

Its members

(referred to as legislative representatives,

judges, magistrates, or Nobles of the Robe) were

expected to register royal edicts, thus writing

them into law. But they could refuse to do so,

in which case the king could still overrule

their decision via mail (lettre de jussion)

or in person (lit de justice).

And it would sound

like this,

"Il

n'appartient point à mon parlement de douter

de mon pouvoir, ni de celui que je lui ai

confié."

In other words:

"It does not

belong to my parliament to doubt my power,

nor that in which I have invested it."

The king could also direct someone to stage a

lit de justice in His Majesty's name.

Lit de justice,

by the way, means literally translated bed of

justice, referring to the original seat that

was created with great pomp for the king when he

visited the parlement in the 14th

century. It was a pimped out portable throne, including

platform, seat, drapes, canopy, and

fleur-de-lis

wall coverings.

fleur-de-lis

wall coverings.

The parlements did not have the power to

create laws on behalf of the nation.

Other than "law

making," the parlements were judges of

civil and criminal cases, in fact, they were the

highest courts of justice, the supreme courts.

In 1789, the jurisdiction

of the parlement of Paris covered a third

of the kingdom, and France had 13 sovereign

courts plus 4 minor courts (Artois, Alsace,

Roussillon, Corsica).

Here is the map

Laws, Courts, Parlements -

France 1789

Depending on the

issue at hand, there were next to the

parlements a few other supreme courts, such

as the

Chambre des Comptes,

the

Chambre des Comptes,

the

Cour des Aides,

the Cour des Monnaies,

and the Châtelet.

Cour des Aides,

the Cour des Monnaies,

and the Châtelet.

::

Sansculottes

A Sansculotte, or Sans-Culotte, was a supporter of the French

Revolution from the poorer or lower class.

Culottes

were knee-breeches worn by the upper classes.

The lower class wore pantalons, or long

trousers. Sans is French for without.

The Sansculottes were associated with an extreme

radical and militant view. Hence, it was also

possible to run into people from the upper class who shared

these views and called themselves Sansculottes

while wearing culottes.

Just FYI, today's culottes look like

this:

Victoria's Secret Boxer Culottes

And if someone

today describes you as being culotté

(adjective), you're being sassy, cheeky, or

daring.

|

|

La Liberté ou la Mort ! – Liberty or

Death!

French Revolution 1789–1799

The French Revolution is also called The Revolution of 1789.

|

|

Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood

was one of the mottos in the French Revolution. Such honorable

goals, however, could not prevent the gruesome

Reign of Terror.

Reign of Terror.

The Revolution also introduced the

guillotine, the infamous device for decapitation, in 1792.

guillotine, the infamous device for decapitation, in 1792.

Image Above

La Liberté ou la Mort ! – Liberty or Death

Gouache by Jean-Baptiste Lesueur,

who lived 1749-1826, and who created this artwork around 1792.

Formerly attributed to Pierre-Etienne

Lesueur.

Underneath it reads on the left:

"LE CRIS FRANCAIS / Des Citoyens de

tous états se rencontrant dans les rues / se réunissoient, et

poussoient ensemble le terrible cris de / La Liberté ou la Mort."

And on the right it reads:

"Départ pour les frontières d'un

Citoyen / Volontaire, accompagné de sa femme, de ses / enfants et

d'une parente son cousin Le / serrurier porte le Havresac."

In other words:

The French cry / Citizens of all

estates come together in the streets / they gather and shout out

unitedly the terrible cry of / Liberty or Death.

A citizen's departure to the frontiers

/ A volunteer, accompanied by his wife, his / children and a

relative his cousin The / locksmith carries the knapsack.

Musée Carnavalet

|

What Caused the French Revolution?

The immediate cause of the French Revolution was France's financial

crisis after having supported the

American Revolution against

Britain.

American Revolution against

Britain.

France was broke. Which lead to the question, Who should come up

with the money — the clergy, the nobility, or the common people?

Which lead to the question, Shouldn't these three social groups be

treated equally when it comes to paying taxes? Which lead to the

question, If everyone is equal, what's a king doing in France?

People were done with the monarchy and wanted a change. (Ironically,

the monarchy returned to power in 1814 with

Louis XVIII.) Louis XVIII.)

But revolutions are never as simple as that.

In a nutshell, the French Revolution was the result of many economical and social

problems.

France Before the Revolution

The Country

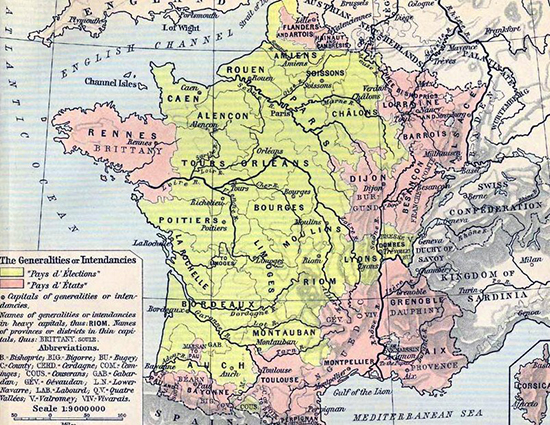

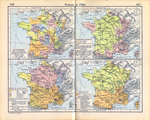

Before the French Revolution, France looked like this on a map:

France before the

Revolution

Click to enlarge

His Majesty the King

The King of France had absolute powers. He was

responsible to God alone, which could heighten his sense of

accountability, but effectively meant

nothing if it didn't.

With God or without, it had become common practice in law making to

consult with His Majesty's ministers.

What were their powers? They could refuse to register the king's

edicts. It was frowned upon not to consider the opinion of his

parlement. But in the end, the King could always overrule his

minister's veto with impunity.

France had no written constitution. Royal power was executed

according to tradition.

The Administration

In 1789, France was divided

into 34 généralités, each one taken care of by a royal

intendant. Here is a map of the generalities or intendancies:

Map of the generalities (généralités) or intendancies

and their capitals.

Click to enlarge.

The French Nation

In 1789, France was the most populated country in Europe.

France represented one sixth of the European population. By 1914, it

was less than one tenth, and in 1950 one fourteenth.

Eighteenth century France had a population of about 26,000,000

people. Around 21,000,000 of them depended on farming.

French society was a social order of privileges.

If you were male and a member of the clergy

(First Estate)

you belonged to a group of about 120,000

people, but you

owned 1/10 of the land. But you had to be a

bishop. There was not much money in being

just a regular priest.

If you were male or female and belonged to the

nobility (Second Estate) you belonged to a group of around

250,000 to 400,000 people,

but you owned 1/5 of the land.

If you were anything else (Third Estate) chances were

50/50 that you couldn't read. Although you

guys owned over 1/4 of the land, it stood in

no proportion to the number of your

population and it was by no means enough to

feed all of you. The Third Estate

represented at least 96% of the French

nation.

Many offices could

be bought or inherited. Attached to these offices came ennoblement

and tax privileges.

And speaking of taxes and tolls, smuggling was rampant to such an

extent that in 1783 a wall was built encircling Paris.

See also

Taxation in

Pre-Revolutionary France.

Taxation in

Pre-Revolutionary France.

The Revolution Builds — Brief Summary

After supporting the Colonists in the

American Revolution

(1775-1783,) France

faced serious national debts. Representatives of clergy, nobility,

and the common people (also called the Third Estate) met at Versailles to discuss their options.

American Revolution

(1775-1783,) France

faced serious national debts. Representatives of clergy, nobility,

and the common people (also called the Third Estate) met at Versailles to discuss their options.

Conflict of interests made negotiations impossible. The deputies of

the Commons finally declared they were prepared to proceed alone,

and, on June 17, 1789, formed a

National Assembly. National Assembly.

The king,

Louis XVI, was not pleased and locked them out of their meeting hall.

Louis XVI, was not pleased and locked them out of their meeting hall.

This prompted the Commons to occupy Louis' indoor tennis court,

taking an oath not to leave until a written constitution had been

agreed upon. This was the Tennis Court Oath

of June 20, 1789.

The Tennis Court Oath, June 20, 1789*

Le Serment du Jeu de Paume, le 20 juin 1789

In the center standing on a table is the astronomer

Jean-Sylvain Bailly, who was

appointed president of the Third Estate on May 5, 1789. He reads the

text of the oath.

Oil on canvas by Jacques-Louis David, who lived

1748-1825.

Musée Carnavalet

*

Please note that the official English

title of this painting might be misleading, especially if you are

into sports. Tennis and Jeu de Paume are obviously not

the same thing.

For

more see here. Thanks Marleen for kindly prodding me

to double clarify this.

On July 10, 1789, the National Assembly was renamed

National Constituent Assembly.

On July 11, 1789, the king fired his popular finance minister,

Jacques Necker.

Jacques Necker.

What Started the French Revolution?

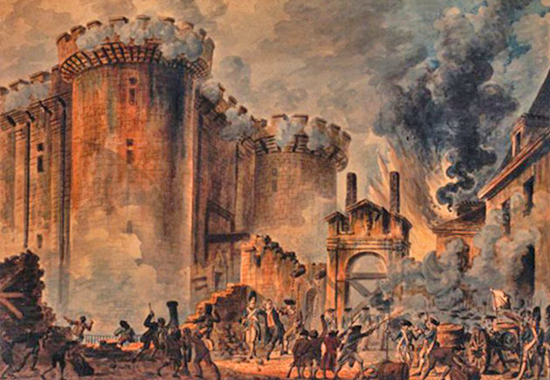

The French Revolution officially begun with the

Storming of

the Bastille on July 14, 1789.

A mob stormed the

Bastille

prison in Paris and demanded from the guards to hand over the arms

and ammunition that were stored there.

The guards refused, the mob

wouldn't take a no for an answer and captured the prison, thus proving that power resided with the people.

The days of the

ancien régime were over.

ancien régime were over.

La Prise de la

Bastille (The Storming of the Bastille)

Illustrated in the

center of the painting is the arrest of

Bernard

Rene Jourdan,

the Marquis de Launay. He was the

last governor of the Bastille.

The mob had him lynched later that day.

Painting

by

Jean-Pierre-Louis-Laurent Houel, 1789.

Bibliothèque

Nationale de France

Here is more on the

Bastille, its history, its

prisoners,

and what it stood for.

Bastille, its history, its

prisoners,

and what it stood for.

The Great Fear of July 1789

Rumors of a conspiracy by the king and the aristocracy prompted

peasants to pillage and burn the houses of nobles and to destroy

feudal records.

This became known as the Great Fear of July 1789. These

developments led

to the abolishment of the feudal regime and the adoption of the

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.

One of the new laws of this declaration seized lands from the Roman

Catholic Church in order to pay the national debt. Additionally, the

church was subjected to severe reorganization.

Pope Pius VI was not amused.

Pope Pius VI was not amused.

King Louis didn't show himself cooperative and the people of Paris

decided to pay him a visit at his castle at Versailles, forcing the

royal family to relocate to the Tuileries Palace at Paris. These were the

October Days (October 5 and 6, 1789.)

CENTRAL

EUROPE 1789

Click map to enlarge

The French Revolution Runs Its Course

Compared with 1789, the year 1790 seemed all in all more harmonious for the French, especially with a

draft of the constitution in their pocket, and with patriotic events

like the

Festival of the Federation

being held etc.

But in 1791,

Louis XVI made a big

mistake when he tried to flee the country.

Louis XVI made a big

mistake when he tried to flee the country.

This act showed everyone who still had doubts, that Louis secretly

desired that the Austrian and Prussian armies would help him restore

absolutism. He was caught, forced to return, and the little

credibility that he had left was gone for good.

Meanwhile, the monarchies of neighboring nations were alarmed by the French

Revolution.

In France, war was desired by royalists and revolutionists alike

because they believed it would rally the nation to their respective

causes.

France declared war against Austria in 1792 and the

French Revolutionary Wars began. French Revolutionary Wars began.

Originally, France experienced reverses, and these made the

French population susceptible to the ideas of extremists. The revolution

turned radical.

The French Republic was proclaimed. The king was tried for treason

and executed. Countless arrests of royalist and supposed

sympathizers followed.

The news of the advance of the

Coalition added panic to radical.

The killing of more than a thousand political prisoners within six

days in 1792 became known as the

Coalition added panic to radical.

The killing of more than a thousand political prisoners within six

days in 1792 became known as the

September Massacres and indicated what was

still to come. September Massacres and indicated what was

still to come.

July 28:

Liberty

Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix

Louvre

Image Above

This painting was created by Delacroix

in 1831. "July 28" refers to July 28, 1830, which puts it in the

middle of the  July Revolution.

The July Revolution was fought for three days — from July 27 to July 29,

1830.

July Revolution.

The July Revolution was fought for three days — from July 27 to July 29,

1830.

How does this painting relate to the

French Revolution?

Let the smart people from the Louvre

explain:

The allegory

of Liberty is personified by a young woman

of the people wearing the Phrygian cap, her

curls escaping onto her neck. Vibrant,

fiery, rebellious, and victorious, she

evokes the Revolution of 1789, the

sans-culotte, and popular sovereignty. In

her raised right hand is the red, white, and

blue flag, a symbol of struggle that unfurls

toward the light like a flame.

...

The towers of

Notre Dame represent liberty and

Romanticism — as they did for  Victor Hugo — and

situate the action in Paris. Their position

on the left bank of the Seine is inexact,

and the houses between the Cathedral and the

river are pure products of the painter's

imagination.

Victor Hugo — and

situate the action in Paris. Their position

on the left bank of the Seine is inexact,

and the houses between the Cathedral and the

river are pure products of the painter's

imagination.

...

This realistic and innovative work, a symbol

of Liberty and the pictorial revolution, was

rejected by the critics, who were used to

more classical representations of reality.

...

It is now

perceived as a universal work — a

representation of romantic and revolutionary

fervor, heir to the historical painting of

the 18th century and forerunner of Picasso's

Guernica in the 20th.

And if you are wondering why Liberty couldn't get her shaving

together, or why the other guy lost sock and pants,

go to the

official site of the Louvre and

read all about it. official site of the Louvre and

read all about it.

Back to the French Revolution of 1789.

The Reign of Terror

Extreme revolutionary actions triggered counterrevolutionary unrest.

This, in turn, was met with even more brutality.

During two years of terror (July 1792 to July 1794) approx. 300,000

suspects were arrested and 16,594 individuals had been condemned to

death by the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Among them was former

Queen Marie Antoinette. Queen Marie Antoinette.

All in all, the victims of the two years of terror were approx.

35,000 to 40,000.

Strictly speaking, the Reign of Terror

refers to the phase from

September 5, 1793, to

September 5, 1793, to

July 28, 1794.

July 28, 1794.

Many died in prison or were killed without trial. Meanwhile, the

revolutionary government had launched a mass military recruitment

(August 1793) and

became victorious at war (the

French Revolutionary Wars.) French Revolutionary Wars.)

The Reign of Terror, now spearheaded by

Robespierre, kept

gaining momentum.

Robespierre, kept

gaining momentum.

Between June 10 and July 21, 1794, also called the

Great Terror, the

terror reached its peak. Within these six weeks, the

Revolutionary Tribunal had 2,554 persons guillotined. Soon,

Robespierre himself was guillotined.

Resistance broke out in form of the White Terror led by the

royalists.

The

Directory, notorious for its corruption, became the new

revolutionary government. This government maintained power for the

remaining four years of the Revolution.

Directory, notorious for its corruption, became the new

revolutionary government. This government maintained power for the

remaining four years of the Revolution.

1769 - 1789

France

What Ended the French Revolution?

By a coup, on November 9-10, 1799,

Napoleon

became First Consul of France and proclaimed the

end of the Revolution. This also

ended the Napoleon

became First Consul of France and proclaimed the

end of the Revolution. This also

ended the

Directory.

Directory.

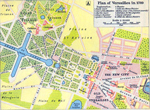

And here's a map of Paris during the Revolution:

MAP OF PARIS DURING

THE REVOLUTION

Click to enlarge

Key Events of the French Revolution — Brief

Timeline

1789, May 5 - The Estates-General (États

généraux) opens session at Versailles.

1789, June 17 -

Formation of the

National Assembly. Unofficially, the

Revolution has just begun.

Formation of the

National Assembly. Unofficially, the

Revolution has just begun.

1789, June 20 -

Tennis Court Oath.

Declared goal to switch from absolute

monarchy to constitutional monarchy.

Hence, a written constitution was

needed.

1789, June 27 -

Louis XVI

orders the clergy and the nobility to

join with the Third Estate in the

National Assembly.

Louis XVI

orders the clergy and the nobility to

join with the Third Estate in the

National Assembly.

1789, July 14 - Storm of the

Bastille.

The Revolution officially begins.

Bastille.

The Revolution officially begins.

1789, August 4 - Abolition of privileges

and the feudal regime.

1789, August 26 and 27 -

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen,

a draft of a constitution.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen,

a draft of a constitution.

1789, October 5 and 6 - The royal family has

to move from Versailles to Paris.

1790, July 14 -

Festival of the

Federation (Fête de la Fédération)

1791, June 21 - The king and his family

try to flee

the country. They are caught at Varennes

and brought back to Paris.

1791, July 17 -

Champs-de-Mars Shooting

(Fusillade du Champs-de-Mars)

1791, August 27 - Austria and Prussia

issue their

Declaration of Pillnitz in

which they call on all European monarchs

to aid in the restoration of the French

monarchy.

1791, September 13 - King Louis XVI

accepts the new constitution. The next

day, he signs it in front of the

National Assembly.

1792, April 20 - War declaration against Austria. The

French Revolutionary Wars

begin.

French Revolutionary Wars

begin.

1792, June 13 - Recall of the Girondin ministers

1792, August 10 - Storming of the Tuileries. Overthrow of the monarchy. France is now a

republic. The First Terror

begins.

1792, August 13 - The royal family is thrown into the Temple

prison.

1792, September 2-6 - September Massacres

1792, September 21 - Formal abolition of the monarchy. The

National

Convention is the new

government of France. National

Convention is the new

government of France.

1792, September 22 - Proclamation of Republic.

First day of the

French Republican Calendar.

French Republican Calendar.

Today is 1 Vendémiaire, year I.

1792, December 25 -

Louis XVI

signs his

Louis XVI

signs his

Last Will

Last Will

1793, January 21 - Execution of

Louis XVI

Louis XVI

1793, March 11 - The

Wars of the Vendée

begin.

Wars of the Vendée

begin.

1793, June 2 - Fall of the Brissotins (Girondins)

1793, June 24 -

Constitution of the Year I

1793, July 13 -

Charlotte Corday, a

Girondin, assassinates Montagnard leader

Jean-Paul Marat in his bath.

Jean-Paul Marat in his bath.

The

Assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday

Oil on canvas by Paul Baudry, who lived

1828-1886

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

1793, September 5 - July 27, 1794 - The Reign of

Terror

1793, September 10 - The National

Convention decrees the Revolutionary

Government until peace is restored.

1793, September 17 - The

Law of Suspects

is passed, authorizing the

creation of revolutionary tribunals to

try those suspected of treason against

the Republic and to punish those

convicted with death.

1793, October 5 - The French republican calendar replaces the

Gregorian calendar. It is implemented retroactively and will be used

until January 1, 1806.

1793, October 16 - Execution of

Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette.

1793, December 4 - The National Convention confirms the creation of

the Revolutionary Government by passing the

Law of 14 Frimaire, year II.

1794, June 8 -

Festival of the Supreme Being (Fête

de l’Être Suprême)

Festival of the Supreme Being (Fête

de l’Être Suprême)

1794, June 10 - Beginning of the Great

Terror

1794, July 28 - Execution of

Robespierre

Robespierre

1795, May 20 - Insurrection of the

Sansculottes

1795, August 22 - Constitution of the year

III

1795, October 27 - The Conseil des Cinq-Cents replaces the

Convention Nationale

1795, October 31 - Inauguration of the

Directory

Directory

1796, April 10 - Beginning of the

Italian Campaign.

Italian Campaign.

1797, September 4 - Coup d'état of 18

Fructidor, year V. Encouraged by Napoleon, the Directory

eliminates the royalists from the government.

1798, May 11 - Coup d'état of 22 Floréal,

year VI. The Directory invalidates half of all elections

to eliminate the Jacobins.

1798, July - Beginning of the

Egypt Campaign.

Egypt Campaign.

1799, November 9

Napoleon takes power

(Coup d'Etat du 18 Brumaire).

The Revolution ends. The Directory is

replaced by the Napoleon takes power

(Coup d'Etat du 18 Brumaire).

The Revolution ends. The Directory is

replaced by the

Consulate.

Consulate.

Political Aftershocks, Mini-Revolutions, and

Coups Following July 14, 1789

Filtered from

the list above, the following events

redefined or challenged the government.

December 4,

1793

Law of 14 Frimaire, year II

The

National Convention

establishes the Revolutionary government.

National Convention

establishes the Revolutionary government.

July 27, 1794

Revolution of 9

Thermidor, year II

The

National Convention ends the Reign of

Terror that was created and kept alive by the Committee

of Public Safety.

National Convention ends the Reign of

Terror that was created and kept alive by the Committee

of Public Safety.

May 20, 1795

Revolt of

1 Prairial, year III

The uprising of the

Sansculottes.

Sansculottes.

September 4, 1797

Coup of 18

Fructidor, year V

The

Directory extracts royalists and other

undesired individuals from the

administration.

Directory extracts royalists and other

undesired individuals from the

administration.

May 11, 1798

Coup of

22 Floréal,

year VI

The

Directory

monkeys with the election results to get rid

of the Jacobins.

Directory

monkeys with the election results to get rid

of the Jacobins.

November 9-10, 1799

Coup of 18-19

Brumaire, year VIII

The Directory ends, the

Consulate begins.

Consulate begins.

May 18, 1804

Proclamation of the Empire

The Consulate declares

Napoleon I Bonaparte

Emperor of France.

Napoleon I Bonaparte

Emperor of France.

French Revolutionary Slipper

Liberty Heels at the Musées de France

More Timelines

Here is a different

French

Revolution Timeline,

illustrating the revolution in the stream of

time alongside the American Revolution and

the American Civil War. French

Revolution Timeline,

illustrating the revolution in the stream of

time alongside the American Revolution and

the American Civil War.

And here are the detailed timelines:

French Revolution

Timeline: 1789

French Revolution

Timeline: 1789

French Revolution

Timeline: 1790

French Revolution

Timeline: 1790

French Revolution

Timeline: 1791

French Revolution

Timeline: 1791

French Revolution timelines for the years

1792-1799 are combined with the French

Revolutionary Wars timelines:

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1792

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1792

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1793

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1793

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1794

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1794

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1795

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1795

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1796

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1796

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1797

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1797

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1798

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1798

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1799

French Revolutionary

Wars Timeline - 1799

See also

Governments

of France Governments

of France

And maybe

Forms of Government

Forms of Government

And here is a chart of the

French armies from

1791-1802, their creation, their

commanders, their timeline.

French armies from

1791-1802, their creation, their

commanders, their timeline.

More French Revolution Maps

1789 France

1789 Paris

1789

Revolutionary Paris

1789

Versailles

1790 France

More History

|