|

For Those Who Read Instruction Manuals: Before and After

The

Guillotine

The

French Revolution

introduced many new concepts and designs. Some were kept,

some were forgotten.

French Revolution

introduced many new concepts and designs. Some were kept,

some were forgotten.

One of these new

ideas was the guillotine, and it was

definitely a keeper.

|

|

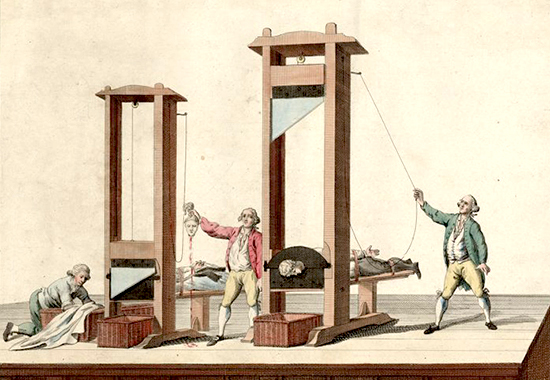

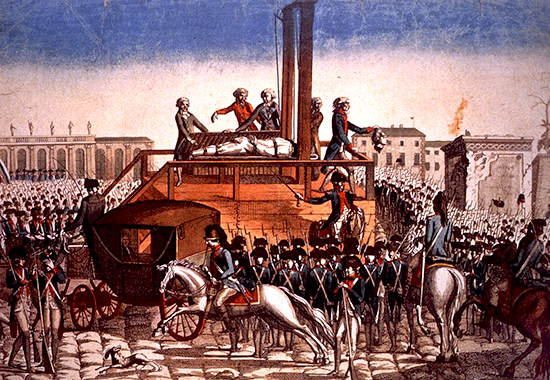

Image Above

Egte

afbeelding van de guillôtine te Parys

Authentic image of

the guillotine in Paris.

Print, Amsterdam

(?), 1795

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département

Estampes et photographie |

In fact, in France, the guillotine was in use from 1792

until 1981.

It was a great success and adopted by

other European states. Even Greece and Hanover had one.

Why Was the

Guillotine Invented?

The guillotine was

invented to make capital punishment a humane experience, as opposed to the

horrors of the tortures of the wheel or the

stake, the unreliable beheading by sword, or the infamy of hanging.

But there was another

revolutionary aspect to it, and that was equality of the death penalty.

Beheading, usually

by sword, was

considered a privilege and reserved for the nobles. The

average criminal was hung or worse.

With the introduction of

the guillotine came the abolition of privileges on

death row.

The Device

The guillotine was a device for

decapitation, invented to execute capital punishment as

swiftly and as neatly as possible.

The apparatus separated head

from body by a

heavy blade that fell down between two upright

posts that were joined by a crossbeam.

Similar

Instruments

Beheading had been a popular way

of execution since people could carry sticks. In time,

decapitation typically involved

swords, axes, or hatchets of sorts.

Inventing a contraption for the

purpose was the logical next step. In England, there

was the

Halifax Gibbet, for

example.

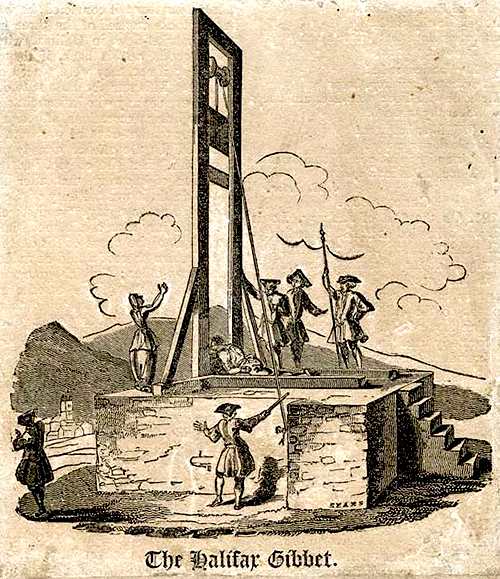

The Halifax

Gibbet, Halifax, Yorkshire

Copyright Calderdale

Council

What was the difference between

the Halifax Gibbet and the common gibbet?

Originally, the gibbet

was synonymous with gallows. Later, it referred to gallows

with dead bodies of criminals hung from it in chains after

execution.

In Scotland, it was

The Maiden that

stood proudly at Edinburgh from 1564 to

1710.

Ironically, James Douglas,

who was the 4th Earl of Morton and the man who invented

The Maiden, ended up on it in 1578. More irony to come.

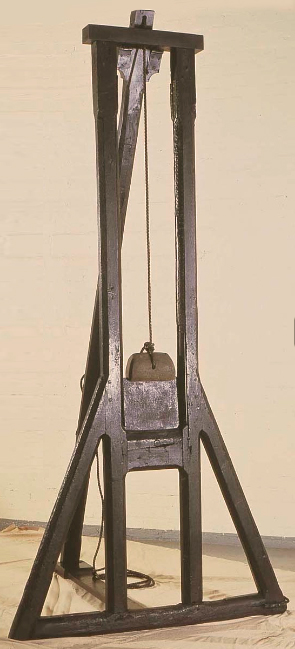

Here is the Scottish Maid:

The Maiden

National Museum of

Scotland

Similar devices were developed all

across Europe, for example by the Germans (who called it diele or

hobel), the Dutch (who brought it to East India),

the Italians (who called it mannaia), the

Russians, the Poles, the Danes, etc.

It was not uncommon, however, that

it took three or four attempts to finish the job. This hacking was generally undesired and to be avoided

if possible.

The guillotine was different in

that it made a swift and clinical cut. Welcome to advanced

beheading.

Who Invented the

Guillotine?

You would think the name gives

it away, but the French doctor and politician

Joseph Ignace Guillotin did not invent

it. He only recommended to develop it.

In a nutshell, Dr. Guillotin had

nothing to do with the plan, the instructions, or

the construction of the instrument that carried his name.

The surgeon

Antoine Louis (born 1723, died in Paris in 1792)

invented the guillotine on paper. The piano maker

Tobias Schmidt (also

spelled Schmitt) built it.

|

|

|

|

|

The Idea |

The Plan |

The Works |

|

Dr. Guillotin |

Dr. Louis |

Mr. Schmidt |

Nicknames

First called Louisette, or

Louison (after Antoine Louis),

it was later nicknamed La Veuve (The Widow), Le Glaive de la

Liberté (The Sword of Freedom), Le Rasoir National

(The National Razor), or Sainte Guillotine.

All of these nicknames were eventually

forgotten in favor of La Guillotine.

Agreeing on

Equality

Dr. Guillotin (born at Saintes

in 1738, died at Paris in 1814) was professor of anatomy at the

University of Paris.

In 1789, Guillotin represented the

Third

Estate as deputy of Paris to the

Third

Estate as deputy of Paris to the

Estates General, then to the Estates General, then to the

National Constituent Assembly.

National Constituent Assembly.

Joseph Ignace Guillotin 1738-1814

Copyright Académie nationale de

médecine

Human rights were a big concern

of the revolutionaries, at least at first, and on August 26, 1789

The Declaration of the Rights of Man

and of the Citizen, or in French The Declaration of the Rights of Man

and of the Citizen, or in French

Declaration des Droits de l'Homme et

du Citoyen, was adopted by the National

Constituent Assembly. Declaration des Droits de l'Homme et

du Citoyen, was adopted by the National

Constituent Assembly.

Article 8 of the Declaration

read:

"La loi ne doit établir que des peines strictement et évidemment

nécessaires."

In other

words:

"The

Law must prescribe only the punishments that are strictly and

evidently necessary."

In the October 9, 1789 session of the National Constituent

Assembly, Dr. Guillotin proposed that all death sentences

should be carried out by beheading, regardless of the

perpetrator's social state or professional rank.

Here are the minutes:

|

From the

National Assembly

Archives parlementaires

9 octobre 1789

page 393

M. Guillotin,

membre de l'Assemblée, a proposé d'ajouter

aux articles décrétés les six articles qui

suivent relatifs aux suppliciés (1) :

Art. 29. Les

mêmes délits seront punis par le même genre

de supplice, quels que soient le rang et

l'état du coupable.

Art. 30. Dans

tous les cas où la loi prononcera la peine

de mort contre un accusé, le supplice sera

le même, quelle que soit la nature du délit

dont il se sera rendu coupable. Le criminel

aura la tête tranchée.

Art. 31. Le

crime étant personnel, le supplice d'un

coupable n'imprimera aucune flétrissure à sa

famille. L'honneur de ceux qui lui

appartiennent ne sera nullement entaché, et

tous continueront d'être également

admissibles à toutes sortes de professions,

d'emplois et dignités.

Art. 32.

Quiconque osera reprocher à un citoyen le

supplice d'un de ses proches, sera puni de .

. .

Art. 33. La

confiscation des biens des condamnés ne

pourra jamais avoir lien, ni être prononcée

en aucun cas.

Art. 34. Le

corps d'un homme supplicié sera délivré à sa

famille, si elle le demande; dans tous les

cas, il sera admis à la sépulture ordinaire,

et il ne sera fait sur le registre aucune

mention du genre de mort.

|

At the session of

December 1,

1789, Guillotin gave a long speech in which he again

suggested that there should be only one kind of punishment

for capital crimes. But this time, he also proposed

to replace the executioner's arm with the action of a

machine.

"With this machine,"

he explained,

"I'll take off your head in the blink of an

eye and you don't suffer."

The Assembly had a nervous giggle

and took down his amended suggestions. Here is an excerpt:

|

Art. II. Dans

tous les cas où la loi prononcera la peine

de mort contre un accusé, le supplice sera

le même, quelle que soit la nature de délit

dont il se sera rendu coupable: le criminel

sera décapité. Il le sera par l'effet d'un

simple mécanisme.

Or in other

words:

Art. II. In

all cases in which the law pronounces the

death penalty against a defendant, the

punishment will be the same, regardless of

the nature of the offense of which he is

guilty: the criminal will be beheaded. It

will be by means of a simple mechanism.

|

Guillotin's proposals were discussed

right after his speech, and some felt that by using his machine, the

people could get accustomed to bloodshed,

whereas the use of fire or the rope would

prevent that.

But it had been a

long day, and Guillotin didn't have a prototype

or a description of his "machine" in his pocket.

So the debate got shelved for the moment.

Agreeing on

Beheading

In mid-1791, the discussion

to reform the Penal Code was in full

swing. So far, the

Assembly only decreed equality of punishment.

On June 3, 1791, the

decapitation for the death penalty was demanded by

Félix Le

Pelletier, which was basically a repetition of Guillotin's

proposition. This time, the Assembly adopted it.

On September 25, 1791, the new

Penal Code

was adopted.

|

The Penal Code

The Penal Code, or in French Code

Pénal, was a set of rules

governing violations and criminal responsibility. Its first

version was adopted in France on September 25, 1791.

::

Background

In the second half of the 18th

century appeared a current against the justice of the Ancien Régime,

which implemented cruel, unorganized, and

arbitrary punishments. In addition, the perpetrators received different

penalties depending on their status.

In 1764, the Italian

Cesare Beccaria

wrote on Des délits et des peines, or On Crimes and

Punishments.

Beccaria said that a sentence must be

"proportionate to the offense and determined by the law,"

and it should not be unnecessary or cruel. He rejected torture and the death penalty.

His work was translated into

French in 1765, and French philosophers were delighted.

|

|

Cesare

Beccaria

1738-1794 |

Dei delitti

e delle pene

Crimes and Punishment |

::

The New Penal Code

In September 1789, the

Constituent Assembly created a Comité pour la réforme de la

jurisprudence criminelle, or Committee for the reform of

criminal jurisprudence, which developed a Penal Code,

supplementing the law of January 21, 1790, on offenses and

crimes.

The Penal Code was adopted by

the deputies on September 25, 1791. Now,

same crimes

were punishable by same penalties regardless

of rank or status.

regardless of the nature

of the offense, the death penalty will only be given in one

form: by decapitation and without torture.

the crime is personal,

the offender's family will not be given infamy.

heresy, magic, and

suicide, for which one did a trial in memory of the

deceased, all these "imaginary crimes" are done with.

The Penal Code was in effect until

Napoleon made some amendments in 1810. (He gave the judge

the option to rule between a minimum and a maximum sentence, for

example.)

|

The National Constituent

Assembly was the French Government until September 30, 1791. On October 1,

1791, the

Legislative Assembly, became its successor.

Legislative Assembly, became its successor.

Agreeing on the

Guillotine

The method of decapitation was

not yet adopted and the death row had to wait until the

administration got their paper work together.

At the

end of 1791, the

Legislative Assembly charged a committee with the task of

studying and building a machine that cut heads.

The committee,

in turn, approached Doctor Antoine Louis of the

Academy de Chirurgie, asking for

his recommendation on the method of beheading.

On March 7, 1792, Louis' advice was

forwarded to the committee.

Bust of

Antoine Louis 1723-1792

Copyright Académie nationale de

médecine

On March 20, 1792, the Legislative

Assembly rendered a decree. The new instrument was adopted.

On March 25, 1792, it was sanctioned by

the King.

So far so good.

But the machine had yet to be

built and perhaps perfected.

At the time had settled at Paris a German,

a man from Strasbourg, now France. His name was

Tobias

Schmidt. A piano maker by trade, Schmidt agreed

to be the carpenter

Louis needed. Based on Louis' instructions, Schmidt crafted the

guillotine and received 824 livres for the

job.

Dress Rehearsal

The first guillotine was

taken to the Bicêtre hospital and three corpses were

decapitated. Apparently, some live sheep had been

previously practiced upon as well.

The experiments turned out

satisfactory.

The First Cut

The new instrument worked for

the first time on April 25, 1792.

It was erected on the Place de Grève

in Paris

for the execution of a robber, Nicolas Jacques Pelletier,

who had attacked a person on October 14, 1791, with several

hits of the stick which resulted in the victim's death.

The first political

guillotinade took place after the

fall of the monarchy on August 10, 1792.

See

First Terror.

First Terror.

The Dramatic Guillotine

Contrary to

earlier concern that

people could get accustomed to too much bloodshed, it was felt that the

quickness of the execution and the lack of visibility took

away from the demonstrative character of restorative

punishment reserved for the enemies of the revolution.

earlier concern that

people could get accustomed to too much bloodshed, it was felt that the

quickness of the execution and the lack of visibility took

away from the demonstrative character of restorative

punishment reserved for the enemies of the revolution.

Thus, the revolutionaries

decided to make a show of it, a theatrical ritual with a

permanent exhibition of the scaffold, slow arrival of the

cart with the prisoners (usually a two-wheeled cart called

the tumbrel),

display of the severed head etc.

Besides the one that was

installed in the market places, portable guillotines

were available that could be brought into the chambers of sentenced

sick offenders.

With the serial

executions of the

Great Terror in June 1794, the

guillotine

earned its dire reputation by producing endless streams of

blood, cheered by hysterical spectators.

Great Terror in June 1794, the

guillotine

earned its dire reputation by producing endless streams of

blood, cheered by hysterical spectators.

After the

Revolution of 9 Thermidor

on July 27, 1794, which ended the Reign of Terror, the

guillotine became a symbol of the barbaric terror of the Republic.

Revolution of 9 Thermidor

on July 27, 1794, which ended the Reign of Terror, the

guillotine became a symbol of the barbaric terror of the Republic.

The

Unpretentious Guillotine

Subsequently, the instrument was

gradually withdrawn from the public eye, away from the

center of the capital.

In 1832, it was

placed at the city gates.

In 1851, before the entrance of

the prison.

In 1872, the scaffold on which it was perched

was abolished.

From 1939, it was only used

indoors of

detention places.

The End of a

Performance

The guillotine was used in France well

into the 20th century. But only eight executions took place between 1965

and, the last one, in 1977.

France

outlawed capital punishment and abandoned the use of the guillotine on October 9,

1981. Here is the law:

Abolition of the Death Penalty in

France, 1981 - PDF

9 Octobre 1981 : Abolition de la peine de mort

Famous People on

the Guillotine — Chronologically

French

King Louis XVI was

guillotined on January 21, 1793.

King Louis XVI was

guillotined on January 21, 1793.

Execution of King Louis XVI

at Paris, 1793

Print by unknown artist

Bibliothèque nationale

de France

Adam Philippe de Custine

(French general) was guillotined on August 27, 1793.

Adam Philippe de Custine

(French general) was guillotined on August 27, 1793.

French

Queen Marie Antoinette

was guillotined on October 16, 1793.

Queen Marie Antoinette

was guillotined on October 16, 1793.

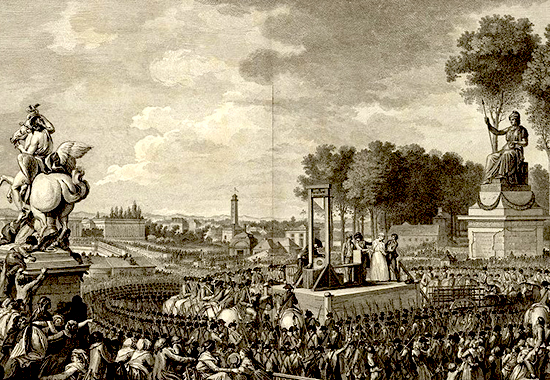

Execution of

Queen Marie-Antoinette at Paris, 1793

Engraving by Isidore-Stanislas Helman

©

Bibliothèque municipale de Versailles

Jacques

Pierre Brissot

(leader of the

Girondins) was guillotined on October 31,

1793.

Girondins) was guillotined on October 31,

1793.

Jean Nicolas

Houchard

(French general) was guillotined on November 17, 1793.

Armand Louis

de Gontaut, duc de Biron

(French general) was guillotined on December 31, 1793.

Jacques

René Hébert (main man of the

sansculottes,

supporter of the

sansculottes,

supporter of the

Reign of Terror) was

guillotined on March 24, 1794. Reign of Terror) was

guillotined on March 24, 1794.

Georges Danton

(First President of the

Georges Danton

(First President of the

Committee of Public Safety) was guillotined on April 5, 1794.

Committee of Public Safety) was guillotined on April 5, 1794.

Camille

Desmoulins (supported the

storming of the

bastille, the abolition of the monarchy, but dared to

criticize the Committee of Public Safety) was guillotined on

April 5, 1794.

storming of the

bastille, the abolition of the monarchy, but dared to

criticize the Committee of Public Safety) was guillotined on

April 5, 1794.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier

(French chemist and tax farmer) was guillotined on May 8,

1794.

Princess

Elizabeth of France (Louis XVI's baby sister) was

guillotined on May 10, 1794.

Maximilien de Robespierre (major contributor of

guillotine candidates) was guillotined on July 28, 1794.

Maximilien de Robespierre (major contributor of

guillotine candidates) was guillotined on July 28, 1794.

Antoine Quentin

Fouquier-Tinville (public prosecuter of the

Revolutioanry Tribunal who put Marie-Antoinette, Brissot,

Desmoulins, and Hébert on the guillotine) was guillotined on

May 7, 1795.

François Noël Babeuf (communist

revolutionary) was guillotined on

May 27, 1797.

François Noël Babeuf (communist

revolutionary) was guillotined on

May 27, 1797.

Voilà, the

history of the guillotine.

More History

|