|

Explorers, Scientists &

Inventors

Explorers, Scientists &

Inventors

Musicians, Painters &

Artists

Musicians, Painters &

Artists

Poets, Writers &

Philosophers

Poets, Writers &

Philosophers

Native Americans & The Wild

West

Native Americans & The Wild

West

First Ladies

First Ladies

Popes

Popes

Troublemakers

Troublemakers

Historians

Historians

Archaeologists

Archaeologists

Royal

Families

Royal

Families

Tribes & Peoples

Tribes & Peoples

Assassinations in History

Who

got slain, almost slain, when, how,

why, and by whom?

Go to the

Assassination Archive

Go to the

Assassination Archive

Online History Dictionary A - Z

Voyages in History

When did what

vessel arrive with whom onboard and where

did it sink if it didn't?

Go to the

Passage-Chart

Go to the

Passage-Chart

The Divine Almanac

Who all roamed the heavens in

olden times? The Who's Who of

ancient gods.

Check out

the Divine Almanac

Check out

the Divine Almanac

|

|

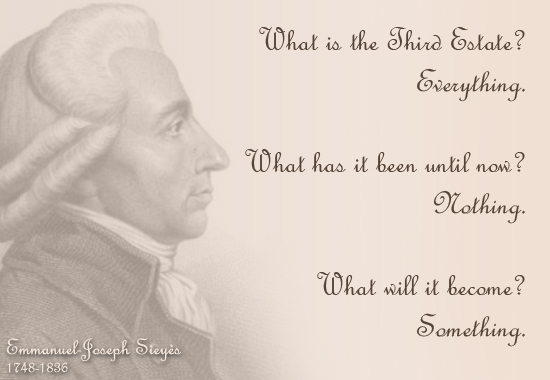

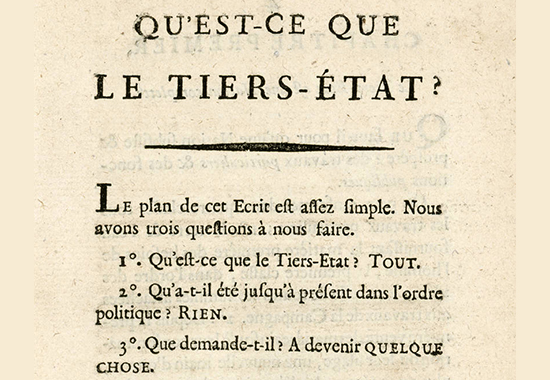

January 1789 —

In his pamphlet What Is the Third Estate?

Sieyès argues that the Third Estate is, in fact, the French

people.

What Is the Third Estate? 1789

In January 1789,

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès wrote his pamphlet

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès wrote his pamphlet

Qu'est-ce que le tiers état?

(What Is the

Third Estate?)

Go here for

the French original.

the French original.

Here is an excerpt translated into

English:

|

|

What is necessary

that a nation should subsist and prosper?

Individual effort and public functions.

[Individual Efforts]

All individual efforts may be included in four

classes:

(1) Since the earth and the waters

furnish crude products for the needs of man, the

first class, in logical sequence, will be that

of all families which devote themselves to

agricultural labor.

(2) Between the first sale

of products and their consumption or use, a new

manipulation, more of less repeated, adds to

these products a second value more or less

composite. In this manner human industry

succeeds in perfecting the gifts of nature, and

the crude product increases twofold, tenfold,

one hundred-fold in value. Such are the efforts

of the second class.

(3) Between production and

consumption, as well as between the various

stages of production, a group of intermediary

agents establish themselves, useful both to

producers and consumers; these are the merchants

and brokers: the brokers who, comparing

incessantly the demands of time and place,

speculate upon the profit of retention and

transportation; merchants who are charged with

distribution, in the last analysis, either at

wholesale or at retail. This species of utility

characterizes the third class.

(4) Outside of

these three classes of productive and useful

citizens, who are occupied with real objects of

consumption and use, there is also need in a

society of a series of efforts and pains, whose

objects are directly useful or agreeable to the

individual. This fourth class embraces all those

who stand between the most distinguished and

liberal professions and the less esteemed

services of domestics.

|

Such are the efforts which sustain society. Who

puts them forth? The Third Estate.

[Public Functions]

Public functions may be classified equally well,

in the present state of affairs, under four

recognized heads: the sword, the robe, the

church, and the administration. It would be

superfluous to take them up one by one, for the

purpose of showing that everywhere the Third

Estate attends to nineteen-twentieths of them,

with this distinction; that it is laden with all

that which is really painful, with all the

burdens which the privileged classes refuse to

carry. Do we give the Third Estate credit for

this? That this might come about, it would be

necessary that the Third Estate should refuse to

fill these places, or that it should be less

ready to exercise their functions. The facts are

well known. Meanwhile they have dared to impose

a prohibition upon the order of the Third

Estate. They have said to it: "Whatever may be

your services, whatever may be your abilities,

you shall go thus far; you may not pass beyond!"

Certain rare exceptions, properly regarded, are

but a mockery, and the terms which are indulged

in on such occasions, one insult the more.

If this exclusion is a social crime against the

Third Estate; if it is a veritable act of

hostility, could it perhaps be said that it is

useful to the public weal? Alas! who is ignorant

of the effects of monopoly? If it discourages

those whom it rejects, is it not well known that

it tends to render less able those whom it

favors? It is not understood that every

employment from which free competition is

removed, becomes dearer and less effective?

In setting aside any function whatsoever to

serve as an appanage for a distinct class among

citizens, is it not to be observed that it is no

longer the man alone who does the work that it

is necessary to reward, but all the unemployed

members of that same caste, and also the entire

families of those who are employed as well as

those who are not? Is it not to be remarked that

since the government has become the patrimony of

a particular class, it has been distended beyond

all measure; places have been created, not on

account of the necessities of the governed, but

in the interests of the governing, etc., etc.?

Has not attention been called to the fact that

this order of things, which is basely and—I even

presume to say—beastly respectable with us, when

we find it in reading the History of Ancient

Egypt or the accounts of Voyages to the Indies,

is despicable, monstrous, destructive of all

industry, the enemy of social progress; above

all degrading to the human race in general, and

particularly intolerable to Europeans, etc.,

etc.? But I must leave these considerations,

which, if they increase the importance of the

subject and throw light upon it, perhaps, along

with the new light, slacken our progress.

It suffices here to have made it clear that the

pretended utility of a privileged order for the public service is

nothing more than a chimera; that with it all that which is

burdensome in this service is performed by the Third Estate; that

without it the superior places would be infinitely better filled;

that they naturally ought to be the lot and the recompense of

ability and recognized services, and that if privileged persons have

come to usurp all the lucrative and honorable posts, it is a hateful

injustice to the rank and file of citizens and at the same time a

treason to the public.

Who then shall dare to say that the Third Estate

has not within itself all that is necessary for

the formation of a complete nation? It is the

strong and robust man who has one arm still

shackled. If the privileged order should be

abolished, the nation would be nothing less, but

something more. Therefore, what is the Third

Estate? Everything; but an everything shackled

and oppressed. What would it be without the

privileged order? Everything, but an everything

free and flourishing. Nothing can succeed

without it, everything would be infinitely

better without the others.

It is not sufficient to show that privileged

persons, far from being useful to the nation,

cannot but enfeeble and injure it; it is

necessary to prove further that the noble order

does not enter at all into the social

organization; that it may indeed be a burden

upon the nation, but that it cannot of itself

constitute a nation.

In the first place, it is not possible in the

number of all the elementary parts of a nation

to find a place for the caste of nobles. I know

that there are individuals in great number whom

infirmities, incapacity, incurable laziness, or

the weight of bad habits render strangers to the

labors of society. The exception and the abuse

are everywhere found beside the rule. But it

will be admitted that the less there are of

these abuses, the better it will be for the

State. The worst possible arrangement of all

would be where not alone isolated individuals,

but a whole class of citizens should take pride

in remaining motionless in the midst of the

general movement, and should consume the best

part of the product without bearing any part in

its production. Such a class is surely estranged

to the nation by its indolence.

The noble order is not less estranged from the

generality of us by its civil and political

prerogatives.

What is a nation? A body of associates, living

under a common law, and represented by the same

legislature, etc.

It is not evident that the noble order has

privileges and expenditures which it dares to

call its rights, but which are apart from the

rights of the great body of citizens? It departs

there from the common order, from the common

law. So its civil rights make of it an isolated

people in the midst of the great nation. This is

truly imperium in imperia.

In regard to its political rights, these also it

exercises apart. It has its special

representatives, which are not charged with

securing the interests of the people. The body

of its deputies sit apart; and when it is

assembled in the same hall with the deputies of

simple citizens, it is none the less true that

its representation is essentially distinct and

separate: it is a stranger to the nation, in the

first place, by its origin, since its commission

is not derived from the people; then by its

object, which consists of defending not the

general, but the particular interest.

The Third Estate embraces then all that which

belongs to the nation; and all that which is not

the Third Estate, cannot be regarded as being of

the nation.

What is the Third Estate?

It is the

whole.

From: Modern

History Sourcebook (Fordham) and Roy Rosenzweig Center who in turn

draws from

Merrick Whitcomb, ed., Translations and

Reprints from the Original Sources of European

History, vol. 6 (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania History Department, 1899), 32–35.

More History

|