|

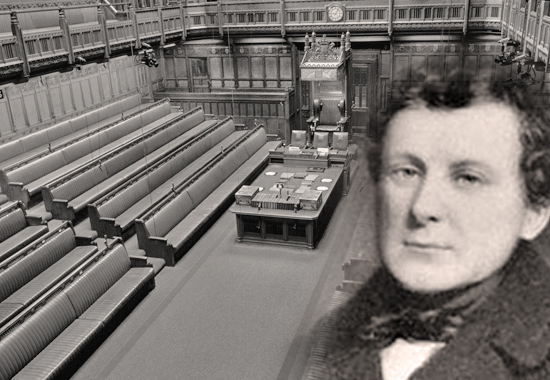

DANIEL O'CONNELL AND THE HOUSE OF

COMMONS

Justice for Ireland

Go here for more about

Daniel O'Connell.

Daniel O'Connell.

Go here for more about

Justice for Ireland speech.

Justice for Ireland speech.

It follows the full text transcript of

Daniel O'Connell's Justice for Ireland speech, delivered

in the House of Commons, London, United Kingdom - February

4, 1836.

|

It appears to me

impossible to suppose that the House will

consider me presumptuous in wishing to be heard

for a short time on this question, especially

after the distinct manner in which I have been

alluded to in the course of the debate. |

If I had no other

excuse, that would be sufficient; but I do not

want it. I have another and a better, the

question is one in the highest degree

interesting to the people of Ireland.

It is, whether we

mean to do justice to that country, whether we

mean to continue the injustice which has been

already done to it, or to hold out the hope that

it will be treated in the same manner as England

and Scotland. That is the question.

We know what lip

service is. We do not want that. There are some

men who will even declare that they are willing

to refuse justice to Ireland; while there are

others who, though they are ashamed to say so,

are ready to consummate the iniquity, and they

do so.

England never did

do justice to Ireland, she never did. What we

have got of it we have extorted from men opposed

to us on principle, against which principle they

have made us such concessions as we have

obtained from them.

The right

honorable baronet opposite [Sir Robert Peel]

says he does not distinctly understand what is

meant by a principle. I believe him. He

advocated religious exclusion on religious

motives. He yielded that point at length, when

we were strong enough to make it prudent for him

to do so.

Here am I calling

for justice to Ireland. But there is a coalition

tonight, not a base unprincipled one, God

forbid! It is an extremely natural one. I mean

that between the right honorable baronet and the

noble lord the member for North Lancashire [Lord

Stanley]. It is a natural coalition, and it is

impromptu, for the noble lord informs us he had

not even a notion of taking the part he has

until the moment at which he seated himself

where he now is.

I know his candor.

He told us it was a sudden inspiration which

induced him to take part against Ireland. I

believe it with the most potent faith, because I

know that he requires no preparation for voting

against the interests of the Irish people.

[Groans.] I thank you for that groan, it is just

of a piece with the rest.

I regret much that

I have been thrown upon arguing this particular

question, because I should have liked to have

dwelt upon the speech which has been so

graciously delivered from the throne today, to

have gone into its details, and to have pointed

out the many great and beneficial alterations

and amendments in our existing institutions

which it hints at and recommends to the House.

The speech of last

year was full of reforms in words, and in words

only. But this speech contains the great leading

features of all the salutary reforms the country

wants, and if they are worked out fairly and

honestly in detail, I am convinced the country

will require no further amelioration of its

institutions, and that it will become the envy

and admiration of the world. I, therefore, hail

the speech with great satisfaction.

It has been observed that the object of a king's

speech is to say as little in as many words as

possible. But this speech contains more things

than words. It contains those great principles

which, adopted in practice, will be most

salutary not only to the British Empire, but to

the world.

When speaking of

our foreign policy, it rejoices in the

cooperation between France and this country. But

it abstains from conveying any ministerial

approbation of alterations in the domestic laws

of that country which aim at the suppression of

public liberty, and the checking of public

discussion, such as a call for individual

reprobation, and which I reprobate as much as

any one.

I should like to

know whether there is a statesman in the country

who will get up in this House and avow his

approval of such proceedings on the part of the

French government. I know it may be done out of

the House amid the cheers of an assembly of

friends. But the government have, in my opinion,

wisely abstained from reprobating such measures

in the speech, while they have properly exulted

in such a union of the two countries as will

contribute to the national independence and the

public liberty of Europe.

Years are coming over me, but my heart is as

young and as ready as ever in the service of my

country, of which I glory in being the

pensionary and the hired advocate. I stand in a

situation in which no man ever stood yet. The

faithful friend of my country, its servant, its

stave, if you will, I speak its sentiments by

turns to you and to itself.

I require no

£

2o,ooo,ooo on

behalf of Ireland. I ask you only for justice.

Will you, can you, I will not say dare you,

refuse, because that would make you turn the

other way. I implore you, as English gentlemen,

to take this matter into consideration now,

because you never had such an opportunity of

conciliating.

Experience makes

fools wise. You are not fools, but you have yet

to be convinced. I cannot forget the year 1825.

We begged then as we would for a beggar's boon.

We asked for emancipation by all that is sacred

amongst us, and I remember how my speech and

person were treated on the Treasury Bench, when

I had no opportunity of reply.

The other place

turned us out and sent us back again, but we

showed that justice was with us. The noble lord

says the other place has declared the same

sentiments with himself, but he could not use a

worse argument. It is the very reason why we

should acquiesce in the measure of reform, for

we have no hope from that House. All our hopes

are centered in this, and I am the living

representative of those hopes.

I have no other

reason for adhering to the ministry than because

they, the chosen representatives of the people

of England, are anxiously determined to give the

same measure of reform to Ireland as that which

England has received. I have not fatigued

myself, but the House, in coming forward upon

this occasion.

I may be laughed

and sneered at by those who talk of my power,

but what has created it but the injustice that

has been done in Ireland? That is the end and

the means of the magic, if you please, the

groundwork of my influence in Ireland.

If you refuse

justice to that country, it is a melancholy

consideration to me to think that you are adding

substantially to that power and influence, while

you are wounding my country to its very heart's

core; weakening that throne, the monarch who

sits upon which, you say you respect; severing

that union which, you say, is bound together by

the tightest links, and withholding that justice

from Ireland which she will not cease to seek

till it is obtained; every man must admit that

the course I am taking is the legitimate and

proper course. I defy any man to say it is not.

Condemn me

elsewhere as much as you please, but this you

must admit. You may taunt the ministry with

having coalesced me, you may raise the vulgar

cry of "Irishman and Papist" against me, you may

send out men called ministers of God to slander

and calumniate me. They may assume whatever garb

they please, but the question comes into this

narrow compass.

I demand, I

respectfully insist, on equal justice for

Ireland, on the same principle by which it has

been administered to Scotland and England. I

will not take less. Refuse me that if you can.

More History

|