|

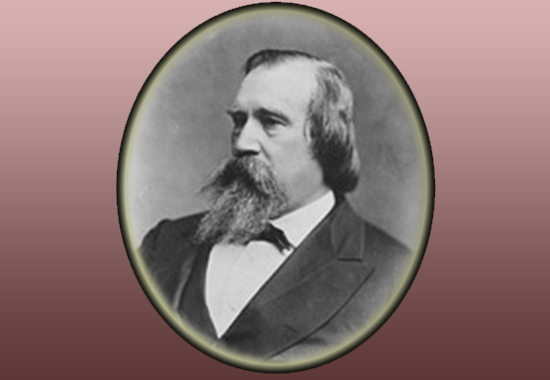

Lucius Q.C. Lamar Speaks in the

House of Representatives

On Sumner and the South

Go here for more about

Lucius Q.C. Lamar.

Lucius Q.C. Lamar.

Go here for more about

Charles Sumner.

Charles Sumner.

Go here for

Lucius Lamar's On Sumner and the

South speech.

Lucius Lamar's On Sumner and the

South speech.

It follows an excerpt from the transcript of

Lucius Q.C. Lamar's speech On Sumner and the

South, delivered in the House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. -

April 25, 1874.

It was certainly a

gracious act on the part of Charles Sumner

toward the South, tho unhappily it jarred on the

sensibilities of the people at the other extreme

of the Union, to propose to erase from the

banners of the national army the mementoes of

the bloody internal struggle which might be

regarded as assailing the pride or wounding the

sensibilities of the Southern people. The

proposal will never be forgotten by that people

so long as the name of Charles Sumner lives in

the memory of man.

But while it

touched the heart and elicited her profound

gratitude, her people would not have asked of

the North such an act of self-renunciation.

Conscious that they themselves were animated by

devotion to constitutional liberty, and that the

brightest pages of history are replete with

evidences of the depth and sincerity of that

devotion, they can but cherish the recollection

of the battles fought and the victories won in

defense of their hopeless cause; and respecting,

as all true and brave men must respect, the

martial spirit with which the men of the North

vindicated the integrity of the Union, and their

devotion to the principles of human freedom,

they do not ask, they do not wish the North to

strike the mementoes of heroism and victory from

either records or monuments or battle-flags.

They would rather that both sections should

gather up the glories won by each section, not

envious, but proud of each other, and regard

them as a common heritage of American valor. Let

us hope that future generations, when they

remember the deeds of heroism and devotion done

on both sides, will speak, not of Northern

prowess or Southern courage, but of the heroism,

courage and fortitude of the Americans in a war

of ideas—a war in which each section signalized

its consecration to the principles, as each

understood them, of American liberty and of the

Constitution received from their fathers.

Charles Sumner in

life believed that all occasion for strife and

distrust between the North and South had passed

away, and there no longer remained any cause for

continued estrangement between those two

sections of our common country. Are there not

many of us who believe the same thing? Is not

that the common sentiment, or if not, ought it

not to be, of the great mass of our people,

North and South? Bound to each other by a common

constitution, destined to live together under a

common government, forming unitedly but a single

member of the great family of nations, shall we

not now at last endeavor to grow toward each

other once more in heart, as we are indissolubly

linked to each other in fortunes? Shall we not,

while honoring the memory of this great champion

of liberty, this feeling sympathizer with human

sorrow, this earnest pleader for the exercise of

human tenderness and heavenly charity, lay aside

the concealments which serve only to perpetuate

misunderstandings and distrust, and frankly

confess that on both sides we most earnestly

desire to be one—one not merely in political

organization; one not merely in community of

language, and literature, and traditions, and

country; but more and better than all that, one

also in feeling and in heart?

Am I mistaken in

this? Do the concealments of which I speak still

cover animosities, which neither time nor

reflection nor the march of events have yet

sufficed to subdue? I can not believe it. Since

I have been here I have scrutinized your

sentiments, as expressed not merely in public

debate, but in the abandon of personal

confidence. I know well the sentiments of these

my Southern friends, whose hearts are so

infolded that the feeling of each is the feeling

of all; and I see on both sides only the seeming

of a constraint which each apparently hesitates

to dismiss.

The

South—prostrate, exhausted, drained of her

life-blood as well as her material resources,

yet still honorable and true—accepts the bitter

award of the bloody arbitrament without

reservation, resolutely determined to abide the

result with chivalrous fidelity. Yet, as if

struck dumb by the magnitude of her reverses,

she suffers on in silence. The North, exultant

in her triumph and elevated by success, still

cherishes, as we are assured, a heart full of

magnanimous emotions toward her disarmed and

discomfited antagonist; and yet, as if under

some mysterious spell, her words and acts are

words and acts of suspicion and distrust. Would

that the spirit of the illustrious dead, whom we

lament to-day, could speak from the grave to

both parties to this deplorable discord, in

tones which would reach each and every heart

throughout this broad territory: My countrymen!

know one another and you will love one another.

More History

|