|

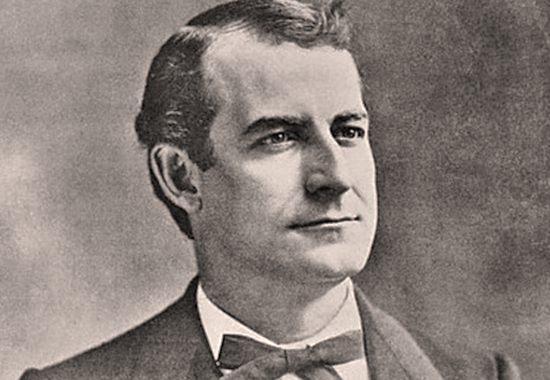

PROMOTING ALTRUISM -

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN 1906

The White Man's Burden

|

Our English

friends, under whose flag we meet tonight,

recalling |

that this is the

anniversary of our nation's birth, would

doubtless pardon us if our rejoicing contained

something of self-congratulation, for it is at

such times as this that we are wont to review

those national achievements which have given to

the United States its prominence among the

nations.

But I hope I shall not be thought lacking in

patriotic spirit if, instead of drawing a

picture of the past, bright with heroic deeds

and unparalleled in progress, I summon you

rather to a serious consideration of the

responsibility resting upon those nations which

aspire to premiership.

This line of

thought is suggested by a sense of propriety as

well as by recent experiences. By a sense of

propriety because such a subject will interest

the Briton as well as the American, and by

recent experiences because they have impressed

me not less with our national duty than with the

superiority of Western over Eastern

civilization.

Asking your attention to such a theme, it is not

unfitting to adopt a phrase coined by a poet to

whom America as well as England can lay some

claim, and take for my text The White Man's

Burden.

Take up the White Man's burden

In

patience to abide

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By

open speech and simple

An hundred times made plain

To seek another's profit

And work another's gain.

Thus sings

Kipling, and, with the exception of the third

line of the meaning of which I am not quite

sure, the stanza embodies the thought which is

uppermost in my mind tonight.

No one can travel

among the dark-skinned races of the Orient

without feeling that the white man occupies an

especially favored position among the children

of men, and the recognition of this fact is

accompanied by the conviction that there is a

duty inseparably connected with the advantages

enjoyed.

There is a white

man's burden, a burden which the white man

should not shirk even if he could, a burden

which he could not shirk even if he would. That

no one "liveth unto himself or dieth unto

himself" has a national as well as an individual

application. Our destinies are so interwoven

that each exerts an influence directly or

indirectly upon all others.

Among the blessings which the Christian nations

are at this time able, and in duty bound, to

carry to the rest of the world, I may mention

five: education, knowledge of the science of

government, arbitration as a substitute for war,

appreciation of the dignity of labor, and a high

conception of life.

In India, in the Philippines, in Egypt, and even

in Turkey, statistics show a gradual extension

of education, and I trust I will be pardoned if

I say that neither the armies nor the navies,

nor yet the commerce of our nations, have given

us so just a claim to the gratitude of the

people of Asia as have our schoolteachers, sent,

many of them, by private rather than by public

funds.

The Christian nations must lead the movement for

the promotion of peace not only because they are

enlisted under the banner of the Prince of

Peace, but also because they have attained such

a degree of intelligence that they can no longer

take pride in a purely physical victory.

Our country has reason to congratulate itself

upon the success of President Roosevelt in

hastening peace between Russia and Japan.

Through him our nation won a moral victory more

glorious than a victory in war. King Edward has

also shown himself a promoter of arbitration,

and a large number of members of Parliament are

enlisted in the same work. It means much that

the two great English speaking nations are thus

arrayed on the side of peace.

Society has passed through a period of

aggrandizement, the nations taking what they had

the strength to take and holding what they had

the power to hold. But we are already entering a

second era, an era in which the nations discuss

not merely what they can do, but what they

should do, considering justice to be more

important than physical prowess. In tribunals

like that of The Hague the chosen

representatives of the nations weigh questions

of right and wrong, and give a small nation an

equal hearing with great and a decree according

to conscience. This marks an immeasurable

advance.

But is another step yet to be taken? Justice

after all is cold and pulseless, a negative

virtue. The world needs something warmer, more

generous. Harmlessness is better than

harmfulness, but positive helpfulness is vastly

superior to harmlessness, and we still have

before us a larger, higher destiny of service.

Even now there are signs of the approach of this

third era, not so much in the actions of

governments as in the growing tendency of men

and women in many lands to contribute their

means, in some cases their lives, to the

intellectual, moral awakening of those who sit

in darkness. Nowhere are these signs more

abundant than in our own beloved land. Before

the sun sets on one of these new centers of

civilization it arises upon another.

While in America and in Europe there is much to

be corrected and abundant room for improvement,

there has never been so much altruism in the

world as there is today, never so many who

acknowledge the indissoluble tie that binds each

to every other member of the race. I have felt

more pride in my own countrymen than ever before

as I have visited the circuit of schools,

hospitals, and churches which American money has

built around the world. The example of the

Christian

nations, though but feebly reflecting the light

of the Master, is gradually reforming society.

On the walls of the temple at Karnak an ancient

artist carved a picture of an Egyptian king. He

is represented as holding a group of captives by

the hair, one hand raising a club as if to

strike them. No king would be willing to confess

himself

so cruel today. In some of the capitals of

Europe there are monuments built from, or

ornamented with, cannon taken in war. That form

of boasting is still tolerated, but let us hope

that it will in time give way to some emblem of

victory which will imply helpfulness rather than

slaughter.

More History

|

|