|

The True Grandeur of Nations

Go here for more about

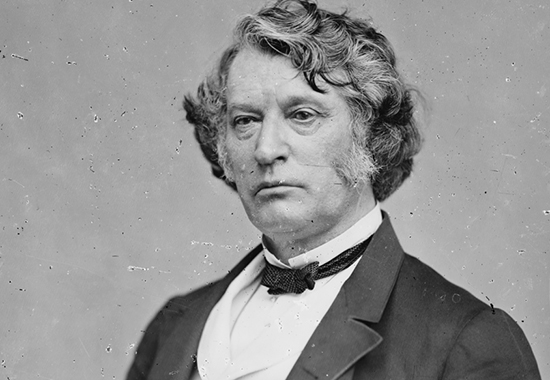

Charles Sumner.

Charles Sumner.

Go here for more about

Charles Sumner's Grandeur of Nations

speech.

Charles Sumner's Grandeur of Nations

speech.

It follows the full text transcript of

Charles Sumner's The True Grandeur of Nations

speech, delivered before the authorities of the city of

Boston on July 4, 1845.

This is page 1 of

2 of Sumner's speech.

Go to page 2.

Go to page 2.

|

In obedience to an

uninterrupted usage of our community, we have

all, on this Sabbath of the Nation, put aside

the common cares of life, and seized a respite

from the never-ending toils of labor, to meet in

gladness and congratulation, mindful of the

blessings transmitted from the Past, mindful

also, I trust, of the duties to the Present and

the Future. May he who now addresses you be enabled so to direct your minds, that you shall not

seem to have lost a day ! |

THE NATIONAL ANNIVERSARY, AND ITS DUTIES

All hearts turn first to the Fathers of the Republic. Their venerable forms rise before us, in

"the procession of successive generations. They

come from the frozen rock of Plymouth, from

the wasted bands of Raleigh, from the heavenly

companionship of William Penn, from the anxious

councils of the Revolution, and from all those

fields of sacrifice, on which, in obedience to the

Spirit of their Age, they sealed their devotion to

duty with their blood. They speak to us, their

children: " Cease to vaunt yourselves of what

you do, and of what has been done for you. Learn

to walk humbly, and to think meekly of yourselves.

Cultivate habits of self-sacrifice and of devotion to

duty. Never aim at aught which is not BIGHT,

persuaded that without this, every possession and

all knowledge will become an evil and a shame ;

and may these words of ours be always in your

minds. Strive to increase the inheritance which

we have bequeathed ; bearing in mind always, that,

if we excel you in virtue, such a victory will be to

us a mortification, while defeat will bring happiness. In this way, you may

conquer us. Nothing is more shameful for a man,

than to found his title to esteem, not on his

own merits, but on the fame of his ancestors.

The Glory of the Fathers is doubtless to their

children a most precious treasure ; but to enjoy

it without transmission to the next generation, and without any addition, this is the height of

imbecility. Following these counsels, when your

days are finished on earth, you will come to join us,

and we shall receive you as friends receive friends ;

but if you neglect our words, expect no happy

greeting then from us." *

* This is borrowed

almost literally from the words attributed by

Plato to the Fathers of Athens, in the beautiful

funeral discourse of the Menezenus.

Honor to the

memory of our Fathers ! May the turf lie gently

on their sacred graves ! Not in words only, but

in deeds also, let us testify our reverence for

their name. Let us imitate what in them was

lofty, pure, and good ; let us from them learn

to bear hardship and privation. Let us, who now

reap in strength what they sowed in weakness, study to enhance the inheritance we have

received. To do this, we must not fold our hands

in slumber, nor abide content with the Past. To

each generation is committed its peculiar task ;

nor does the heart, which responds to the call of

duty, find respite except in the world to come.

Be ours, then, the task which, in the order of

Providence, has been cast upon us ! And what is

this task? How shall we best perform our appointed part ? What can we do, to

make our coming welcome to our Fathers in the skies, and draw

to our memory hereafter the homage of a grateful

posterity? How may we add to the inheritance

received ? The answer cannot fail to interest all,

particularly on this festival, when we celebrate

the Nativity of the Republic. In truth, it well

becomes the patriot citizen, on this anniversary,

to consider the national character, and how it may

be advanced as the good man dedicates his

birthday to meditation on his life, and to aspiration for its improvement. Avoiding, then, all

customary exultation in the abounding prosperity

of the land, and in that Freedom, whose influence

is widening to the uttermost circles of the earth,

let us turn our thoughts on the character of our

country, and humbly endeavor to learn what we must

do, to the end that the Republic may best secure the

rights and happiness of the people committed to

its care ; that it may perform its part in the

World's History ; that it may fulfill the aspirations of generous hearts ; and, practising that

righteousness which exalteth a Nation, thus attain to the heights of True Grandeur.

TRUE GRANDEUR OF NATIONS NOT IN WAR

With this aim, and believing that I can in no

other way so fitly fulfill the trust reposed in me when I was selected as the

voice of Boston, on this welcome Anniversary, I

propose to consider what, in our age, are the

true objects of National Ambition what is truly

National Honor National Glory WHAT is THE TRUE GRANDEUR OP

NATIONS. I would not depart from the modesty

that becomes me, but I am not without hope that

I may contribute something to rescue these

terms, now so powerful over the minds of men,

from the mistaken objects to which they are applied, from deeds of War, and

the extension of empire, that they may be

reserved for works of JUSTICE and BENEFICENCE.

The subject may be

novel, on an occasion like the present; but it

is comprehensive and transcendant in importance.

It raises us to the contemplation of things that are not temporary or

local in character ; but which belong to all ages

and countries ; which are as lofty as Truth, as

universal as Humanity. Nay, more ; it practically

concerns the general welfare, not only of our own

cherished Republic, i>ut of the whole Federation

of Nations. At this moment, it derives a peculiar

and urgent interest from transactions in which

we are unhappily involved. On the one side, by

an act of unjust legislation, extending our power

over Texas, we have endangered Peace with

Mexico ; while, on the other, by the petulant

assertion of a disputed claim to a remote territory beyond the Rocky Mountains, we have

kindled anew, on the hearth of our Mother Country, the smothered fires of hostile strife. Mexico

and England both aver the determination to vindicate what is called the National Honor; and

our Government now calmly contemplates the

dread Arbitrament of War, provided it cannot

obtain what is called an honorable Peace.*

* The official

paper at Washington has said, "We presume the

negotiation is really resumed, and will be

prosecuted in this city, and not in London, to

some definite conclusion peaceably, we should

hope but we wish for no peace but an honor" able

peace."

Far be from our country and our age the sin and

shame of contests hateful in the sight of God and

all good men, having their origin in no righteous

though mistaken sentiment, in no true love of

country, in no generous thirst for fame, that last

infirmity of noble minds ; but springing in both

cases from an ignorant and ignoble passion for new

territories ; strengthened, in one case, by an unnatural desire, in this land of boasted freedom, to

fasten by new links, the chains which promise soon

to fall from the limbs of the unhappy slave ! In

such contests, God has no attribute which can join

with us. Who believes that the National Honor

will be promoted by a war with Mexico, or a war

with England? What just man would sacrifice a

single human life, to bring under our rule both

Texas and Oregon? An ancient Roman, a stranger

to Christian truth, touched only by the relations of

fellow-countryman, and not of. fellow-man said, as

he turned aside from a career of Asiatic conquest,

that he would rather save the life of a single citizen, than become master of all the dominions of

Mithridates.

A war with Mexico

would be mean and cowardly ; with England it

would be bold at least, though parricidal. The

heart sickens at the murderous attack upon an

enemy, distracted by civil feuds, weak at home,

impotent abroad ; but it recoils in horror from

the deadly shock between children of a common

ancestry, speaking the same language, soothed in

infancy by the same words of love and tenderness, and hardened into vigorous manhood under

the bracing influence of institutions drawn from the

same ancient founts of freedom. Curam acuebat,

quod adversus Latinos bellandum erat, lingua, mori

bus, annorum genere, institutis ante omnia militaribus, congruentes; milites militibus, centurionibus

centuriones, tribuni tribunis compares, collegceque,

iisdem pracesidiis, scepe iisdem manipulis permixti

fuerant.*

* Liv. VIII. c. 6.

IN OUR AGE THERE CAN BE NO PEACE THAT IS NOT

HONORABLE ; THERE CAN BE NO WAR THAT IS NOT

DISHONORABLE. The True Honor of a Nation is to

be found in deeds of Justice and Beneficence,

securing and advancing the happiness of its

people, inconsistent with War. In the clear eye

of Christian judgment, vain are its victories ;

infamous are its spoils. He is the benefactor,

and worthy of Honor, who brings, comfort where

before was . wretchedness ; who dries the tear

of sorrow ; who pours oil into the wounds of the

unfortunate ; who feeds the hungry and clothes

the naked ; who does H V. justice ; who

enlightens the ignorant ; who unlooses the

fetter of the slave ; who, by virtuous genius,

in art, in literature, in science, enlivens and

exalts the hours of life ; who, by word, or

action, inspires a love for God and for man.

This is the Christian hero; this is the man of

Honor in a Christian land. He is no benefactor,

nor deserving of Honor, whatever his worldly

renown, whose life is passed in feats of brute

force ; who renounces the great law of Christian

brotherhood ; whose vocation is blood. Well may

old Sir Thomas Browne exclaim, " The world does

not know its Greatest Men ; " for thus far it

has chiefly discerned the violent brood of

battle, the armed men springing up from the dragon's teeth sown by Hate, and cared little for the

Truly Good Men, children of Love, guiltless of

their country's blood, whose steps on earth have

been noiseless as an angel's wing.

It must not be disguised that this standard differs

from that of the world down to this day. The voice

of man is yet given to praise of military chieftains ;

and the honors of victory are chanted even by the

lips of woman. The mother, while rocking her

infant on the knee, stamps upon his tender mind, at

that age more impressible than wax, the images of

War ; she nurses his slumbers with its melodies ;

pleases his waking hours with its stories ; and

selects for his playthings the plume and the sword.

From the child is formed the man ; and who can

weigh the influence of a mother's spirit on the

opinions of later life ? The mind which trains the

child is like the hand that commands the end of a

long lever; a gentle effort at that time suffices to

heave the enormous weight of succeeding years.

As the boy advances to youth, he is fed like

Achilles, not on honey and milk only, but on bear's

flesh and lion's marrow. He draws the nutriment

of his soul from a literature, whose beautiful fields

have been moistened by human blood. Fain would

I offer my tribute to the Father of Poetry, standing

with harp of immortal melody, on the misty mountain-top of distant antiquity ;

to those stories of courage and sacrifice which

emblazon the annals of Greece and Rome ; to the

fulminations of Demosthenes and the splendors of Tully ; to the sweet

verse of Virgil and the poetic prose of Livy. Fain

would I offer my tribute to the new literature, which

shot up in modern times as a vigorous forest from

the burnt site of ancient woods ; to the passionate

song of the Troubadour of France, and the Minnesinger of Germany ; to the thrilling ballad of Spain,

and the delicate music of the Italian lyre. But

from all these has breathed the breath of War, that

has swept the heart-strings of thronging generations

of men !

And when the youth becomes a man, his country

invites his service in War, and holds before his

bewildered imagination the prizes of worldly Honor.

For him is the pen of the historian, and the verse

of the poet. His soul is taught to swell at the

thought that he also is a soldier ; that his name

shall be entered on the list of those who have borne

arms for their country'; and perhaps he dreams that

he too, may sleep, like the Great Captain of Spain,

with a hundred trophies over his grave. The law

of the land throws its sanction over this madness.

The contagion spreads beyond those on whom is

imposed any positive obligation. Peaceful citizens

volunteer to appear as soldiers, and to affect in dress,

arms, and deportment, what is called " the pride,

pomp, and circumstance of glorious war." The ear-piercing fife has today filled our streets, and we

have come to this Church on this National Sabbath,

by the thump of drum, and with the parade of

bristling bayonets.

It is not strange, then, that the Spirit of War

still finds a home among us ; nor that its Honors

continue to be regarded. All this may seem to give

point to the bitter philosophy of Hobbes, who

declared that the natural state of mankind was war,

and to sustain the exulting language of the soldier

in our own day, who has said, " War is the condition of this world. From

man to the smallest insect, all are at strife,

and the glory of arms, which cannot be obtained

without the exercise of honor, fortitude,

courage, obedience, modesty, and temperance, excites the brave man's patriotism, and is a

chastening correction of the rich man's pride." *

This is broad and bold. In different mood, another

British general is reported as saying, " Why, man,

do you know that a grenadier is the greatest character in this world ; " and, after a moment's pause, with

the added emphasis of an oath, " and I believe, in

the next too." f All these spoke in harmony. If

one is true, then all are true.

* Napier, Penins. War, VI. 688.

Southey's Colloquies on the Progress of Society, vol. i. p. 211.

Alas ! in the existing relations of nations, the infidel

philosopher, and the rhetorical soldier, to say

nothing of the giddy general, find too much

support for a theory which slanders human

nature, and insults the goodness of God. It is true that there

are impulses in us which unhappily tend to strife.

There are propensities, that we have in common

with the beast, which, if not kept in subordination

to what in man is human, or, perhaps, divine, will

break forth in outrage. This is the predominance

of the animal qualities. Hence come wars and

fightings, and the false glory which crowns such

barbarism. But the Christian elevation of nations,

as of individuals, may well be determined by the

extent to which these evil dispositions are restrained. Nor does the Christian teacher ever

perform his high office more truly than when, recognizing the supremacy of the moral and intellectual faculties, he calls upon nations, as upon

individuals, to declare independence of the bestial

propensities, to abandon practices founded on these

propensities, and in every way to beat down that

profane spirit which is the genius of war. In making this appeal, he will be startled by the fact, as

discreditable as important, that, while the municipal law of each Christian nation discarding the Arbitrament of Force provides a judicial tribunal

for the determination of controversies between individuals, International law expressly establishes the

Arbitrament of War for the determination of controversies between nations.

Here, then, in unfolding the True Grandeur of

Nations, we encounter a practice, or custom, sanctioned by the Law of Nations, and constituting a

part of that law, which exists in defiance of principles, such as no individuals can disown. If it is

wrong and , inglorious in individuals to consent

and agree to determine their petty controversies

by combat, it must be equally wrong and inglorious

for nations to consent and agree to determine their

vaster controversies by combat. Here is a positive,

precise, and specific evil, of gigantic proportions

inconsistent with all that is truly honorable making within the sphere of its influence all True

Grandeur impossible and it does not proceed

from any uncontrollable impulses of our nature,

but is expressly established and organized by law.

DEFINITION OF WAR

As all citizens are parties to municipal law, and

are responsible for its institutions, so are all the

Christian nations parties to International Law,

and responsible for its provisions. By recognizing

these provisions, nations consent and agree beforehand to the Arbitrament of War, precisely as citizens, by recognizing Trial by Jury, consent and

agree beforehand to the latter tribunal. As to

understand the true nature of Trial by Jury, we

first repair to the municipal law by which it is

established : so, to understand the true nature of

the Arbitrament of War, we must first repair to the

Law of Nations.

Writers, of transcendent genius and learning, have

defined this Arbitrament, and laid down the rules

by which it is governed, constituting a complex

code, with innumerable subtle provisions, regulating

the resort to it, and the manner in which it shall

be conducted, called the Laws of War. In these

quarters, we catch our first authentic glimpse

of its folly and wickedness. War is called by

Lord Bacon, " One of the highest Trials of

Right, when princes and states, that acknowledge

no superior upon earth, shall put themselves

upon the justice of God for the deciding of

their controversies, by such success as it shall

please Him to give on either side." (Works, vol.

iii. p. 40.) This definition of the English

philosopher has been adopted by the American

jurist, Chancellor Kent, in his authoritative Commentaries on American Law (vol. i.

p. 46). The Swiss Professor, Vattel, whose work

is regarded as an important depository of the Law

of Nations, defines War as " that state in which we

prosecute our rights by Force" (Book III. ch. i.

1.) In this, he very nearly follows the eminent

Dutch authority, Bynkershoek, who says : "Bellum est eorum, qui suae potestatis sunt ; juris

sui persequendi ergo, concertatio per vim vel dolum."

(Qucest. Jur. Pub. Lib. I. ch. vi.) Mr. Whewell,

who has done so much to illustrate philosophy in

all its departments, says, in his recent work on

the elements of Morality and Polity, " Though

War is appealed to, because there is no other

ULTIMATE TRIBUNAL to which states can have recourse, it is appealed to for justice" (Vol. ii.

1146.) And in our country, Dr. Lieber says,

in a work abounding in learning and sagacious

thought (Political Ethics, vol. ii. 643), that War

is a mode of obtaining rights, a definition which

hardly differs in form from that of Vattel and

Bynkershoek.

In harmony with these definitions, let me define

the Evil which I now arraign. War is a public

armed contest between nations, under "the sanction

of International Law, to establish JUSTICE between

them; as, for instance, to determine a disputed

boundary line, or the title to territory.

This definition,

it will be perceived, is confined to contests

between nations. It is restrained to International War. It carefully excludes the

question, so often agitated, of the right of

revolution, and that other question, on which

the friends of Peace sometimes differ, the right

of personal self-defense. It does not in any way

involve the question, of the right to employ

force in the administration of justice, or in the conservation of domestic quiet.

It is true that the term defensive is always

applied to Wars in our day. And it is creditable

to the moral sense of nations, that they feel constrained to allege this seeming excuse, although

its absurdity is attested by the fact, that it is

advanced equally by each belligerent party. It

is unreasonable to suppose that War can arise in

the present age, under the sanctions of International Law, except to determine an asserted right.

Whatever may have been its character in periods

of barbarism, or when invoked to repel an incursion

of robbers or pirates the enemies of the human

race War becomes in our day, among all the

nations who are parties to existing International

Law, simply a mode of litigation, or of deciding a

Lis Pendens, between these nations. It is a mere

TRIAL OF RIGHT. It is an appeal for justice to

Force. The Wars that now lower from Mexico

2*

and from England are of this character. On the

one side, we assert a title to Texas, which is disputed; and on the other, we

assert a title to Oregon, which is disputed. It

is only according to " martial logic," or the

"flash language" of a dishonest patriotism, that the Ordeal by Battle in these causes

can be regarded, on either side, as defensive War.

Nor did the threatened War with France in 1834

promise to assume any different character. Its

professed object was to secure the payment of five

million dollars in other words, to determine by

this Ultimate Tribunal a simple question of justice.

And, going back still further in our history, the

avowed purpose of the War declared by the United

States against Great Britain in 1812, was to obtain

from the latter Power an abandonment of her claim

to search American vessels. Unrighteous as was

this claim, it is plain that War was here invoked

only as a Trial of Right.

But it forms no part of my purpose to consider

individual Wars in the Past, except so far as necessary by way of example. My

aim is above this. I wish to expose the

irrational, cruel, and impious custom of War, as

sanctioned by the Law of Nations. On this account, I resort to that supreme

law, for my definition. And here, let me be understood as planting myself on this definition. This is

the foundation of the argument which I venture to

submit.

ORDER OF TREATMENT

When we have

considered, in succession, first, the character

of War; secondly, the miseries it produces ; and, thirdly, its utter and shameful insufficiency, as a mode of determining justice,

we may be able to decide, strictly and logically,

whether it must not be ranked with crimes from

which no True Honor can spring, to individuals

or nations, but rather condemnation and shame.

It will then be important, in order to appreciate

this Evil, and the necessity for its overthrow, to

pass in review the various prejudices by which War

is sustained, and especially that most pernicious

prejudice, in obedience to which, uncounted sums

are diverted from purposes of Peace to PREPARATIONS FOR WAR.

THE ANIMAL CHARACTER OF WAR

I. And first, as to the character of War, or that

part of our nature in which it has its origin. Listen to the voice of the ancient poet of Boeotian

Ascra :

This is the law for mortals, ordained by the Ruler of Keayen ;

Fishes and Beasts and Birds of the air devour each other ;

JUSTICE dwells not among them ; only to MAN has he given

JUSTICE the Highest and Best.*

* Hesiod, Works

and Days, v. 276-279 . Cicero also says : Neque ulla re longius absumus a natura ferarum, in quibus in

esse fortitudinern ssepe dicimus, ut in equis, in leonibus ; justitiarn, equitatem, bonitatem non dicimus. De Offic. Lib. L cap. 16.

These words of the early Hesiod exhibit the distinction

between man and the beast ; but this very

distinction belongs to the present discussion.

The first idea that rises to the mind, is, that

War is a resort to brute Force, whereby

each nation strives to overpower the other.

Reason, and the divine part of our nature, in

which alone we differ from the beast, in which

alone we approach the Divinity, in which alone

are the elements of justice, the professed

object of War, are dethroned. It is, in short, a

temporary adoption, by men, of the character of beasts, emulating their ferocity, rejoicing

like them in blood, and seeking, as with a lion's

paw, to hold an asserted right. In more recent

days, this character of War is somewhat disguised,

by the skill and knowledge which it employs ; it

is, however, still the same, made more destructive

by the genius and intellect which have become its

servants. The primitive poets, in the unconscious

simplicity of the world's childhood, make this boldly

apparent. The heroes of Homer are likened in

rage to the ungovernable fury of animals, or to

things devoid of reason or affection. Menelaus

presses his way through the crowd, " like a beast."

Sarpedon is aroused against the Argives, "as a

lion against the crooked-horned oxen ; " and afterwards rushes forward, " like a lion nourished on

the mountains for a long time famished for want

of flesh, but whose courage compels him to go even

to the well-guarded sheepfold." The great Telamonian Ajax in one and the same passage is likened

to " a beast," " a tawny lion," and " an obstinate

ass ; " and all the Greek chiefs, the flower of the

camp, are described as ranged about Diomed, " like

raw-eating lions, or wild boars whose strength is

irresistible." Even Hector, the hero in whom

cluster the highest virtues of polished War, is

called by the characteristic term, " the tamer of

horses ; " and one of his renowned feats in battle,

indicating brute strength only, is where he takes

up and hurls a stone, which two of the strongest

men could not easily put into a wagon ; and he

drives over dead bodies and shields, while the axle

is defiled by gore, and the guard about the seat,

sprinkled from the horse's hoofs, and from the tires

of the wheels ; and, in that most admired passage

of ancient literature, before returning his child, the

young Astyanax, to the arms of the wife he is

about to leave, he invokes the gods for a single

blessing on the boy's head, "that he may excel his

father, and bring home bloody spoils, his enemy

being slain, and so make glad the heart of his

mother!"

From the early fields of modern literature, as

from those of antiquity, similar illustrations might

be gathered, all showing the unconscious degradation of the soldier, who, in the

pursuit of justice, renounces the human character, to assume that of the

beast. Henry V., as represented by our own Shakespeare, in the spirit-stirring

appeal to his troops, says :

When the blast

of war blows in our ears, Then imitate the

action of the tiger.

This is plain and

frank, and reveals the true character of War.

I need not dwell on the moral debasement that

must ensue. The passions are unleashed like so

many blood-hounds, and suffered to rage. All the

crimes which fill our prisons stalk abroad, plaited

with the soldier's garb, and unwhipt of justice.

Murder, robbery, rape, arson, theft, are the sports

of this fiendish Saturnalia, when

The gates of mercy shall be all shut up,

And the fleshed soldier, rough and hard of heart,

In the liberty of bloody hand shall range

With conscience wide as hell.

Such is the foul

disfigurement which War produces in man, of whom it has been so beautifully

said, " How noble in reason, how infinite in faculties ! in form and moving, how express and admirable ! in action, how like an angel ! in apprehension,

how like a god ! "

CONSEQUENCES OP WAR, AND ITS HORRORS

II. The immediate effect of War is to sever all

relations of friendship and commerce between the

belligerent nations, and every individual thereof,

impressing upon each citizen, or subject, the character of enemy. Imagine this change between England and the United States. The innumerable ships

of the two countries, the white doves of commerce,

bearing the olive of peace, are driven from the sea,

or turned from their proper purpose to be ministers

of destruction ; the threads of social and business

intercourse, so carefully woven into a thick web,

are suddenly snapped asunder ; friend can no longer

communicate with friend ; the twenty thousand

letters, which are speeded each fortnight from this

port alone, can no longer be sent ; and the human

affections, of which they are the precious expression,

seek in vain for utterance. Tell me, you who have

friends and kindred abroad, or who are bound to

foreigners by more worldly relations of commerce,

are you prepared for this rude separation ?

This is little, compared with what must follow.

It is but the first portentous shadow of the disastrous eclipse, the twilight usher of thick darkness,

covering the whole heavens as with a pall, broken

only by the blazing lightnings of battle and siege.

These horrors redden every page of history ;

while, to the scandal of humanity, they have never

wanted historians to describe them, with feelings

kindred to those by which they were inspired. The

demon that has drawn the sword, has also guided

the pen. The favorite chronicler of modern

Europe, Froissart while bestowing his equal

admiration upon braver}'" and cunning, upon the

courtesy which pardoned, as upon the rage which

caused the flow of blood in torrents dwells with

especial delight on "beautiful captures," " beautiful

rescues," " beautiful prowesses," and " beautiful

feats of arms ; " and he wantons in picturing the

assaults of cities, " which, being soon gained by

force, were robbed, and put to the sword without

mercy, men, and women, and children, while the

churches were burnt." *

* Froissart, c.

178, p. 68.

This was in a barbarous

age. But popular writers, in our own day, dazzled

by false ideas of greatness, at which reason and

Christianity blush, do not hesitate to dwell on similar scenes with terms of

rapture and eulogy. Even the beautiful soul of

Wilberforce, which sighed " that the bloody laws

of his country sent many unprepared into another

world," by capital punishment, could hail the slaughter of Waterloo, on

the Sabbath that he held so holy, by which thousands were hurried into eternity, as " a splendid

victory." *

* Life of

Wilberforce, IV. 256, 261.

My present purpose is, less to judge the writer,

than to expose the horrors on horrors which he

applauds. At Tarragona, above six thousand human beings, almost all defenseless,

men and women, gray hairs and infant innocence,

attractive youth and wrinkled age, were

butchered by the infuriate troops in one night,

and the morning sun rose upon a city whose

streets and houses were inundated with blood.

And yet this is called " a glorious exploit."

*

* Alison, Hist, of

French Rev. VIII. 114.

Here was a conquest by the French. At

a later day, Ciudad Rodrigo was stormed by the

British ; when in the license of victory, there ensued a savage scene of plunder and violence, while

shouts and screams on all sides, mingled fearfully

with the groans of the wounded. The churches

were desecrated, the cellars of wine and spirits

were pillaged; fire was wantonly applied to the

city ; and brutal intoxication spread in every direction. Only when the drunken men dropped from

excess, or fell asleep, was any degree of order

restored ; and yet the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

is pronounced " one of the most brilliant exploits

of the British army." *

* Alison,

Hist. VIII. 189.

This " beautiful feat of

arms " was followed by the storming of Badajoz,

in which the same scenes were enacted again, with added atrocities. Let the

story be told in the words of a partial

historian, who saw what he so eloquently

describes. " Shameless rapacity, brutal

intemperance, savage lust, cruelty and murder,

shrieks and piteous lamentations, groans,

shouts, imprecations, the hissing of fire

bursting from the houses, the crashing of doors

and windows, and the report of muskets used in

violence, resounded for two days and nights in

the streets of Badajoz ! On the third, when the

city was sacked, when the soldiers were exhausted by their excesses, the tumult

rather subsided than was quelled ! The wounded

were then looked to, the dead disposed of." *

* Napier, History

of Penins. War, IV. 431.

The same terrible War affords another instance

of the atrocities of a siege, which cries to Heaven

for judgment. For weeks before the surrender of

Saragossa, the deaths were from four to five hundred daily ; the living were

unable to bury the dead, and thousands of

carcasses, scattered in streets and court-yards,

or piled in heaps at the doors of churches, were

left to dissolve in their own corruption, or be

licked up by the flames of the burning houses.

The city was shaken to its foundation, by

sixteen thousand shells thrown during the

bombardment, and the explosion of forty-five

thousand pounds of powder in the mines ; while

the bones of forty thousand persons, of every

age and both sexes, bore dreadful testimony to

the unutterable cruelty of War.

These might seem

to be pictures from the age of Alaric, Scourge

of God, or of Attila, whose boast was, that the grass did not grow where his horse

had set his foot ; but no ! they belong to our own

times. They are portions of the wonderful but

wicked career of him who stands forth as the foremost representative of worldly Grandeur. The

heart aches, as we follow him and his marshals

from field to field of Satanic Glory,* finding everywhere, from Spain to Russia, the same carnival of

woe.

*A living poet of

Italy, who will be placed by his prose among the

great names of his country's literature, in a

remarkable ode, which, he has thrown on the

Urn of Napoleon, leaves to posterity to judge

whether his career of battle was True Glory.

Fu vera gloria? Aiposteri

L'ardua sentenza. -

Manzoni, II Cinque Maggio.

When men learn to appreciate moral Grandeur, the easy sentence

will be rendered.

The picture is various, yet identical in character. Suffering, wounds, and death in every form,

fill the terrible canvas. What scene more dismal

than that of Albuera, with its horrid piles of corpses,

while all night the rain pours down, and river,

hill, and forest, on each side, resound with the

cries and groans of the dying ? What scene more

monumental than that at Salamanca, where, long

after the great battle, the ground, strewn with

fragments of casques and cuirasses, was still blanched by the skeletons of those

who fell? What catalogue of horror more complete

than the Russian campaign? At every step there

is war, and this is enough ; soldiers black with

powder ; bayonets bent with the violence of the

encounter ; the earth ploughed with cannon-shot;

trees torn and mutilated ; the dead and dying ; wounds and

agony; fields covered with broken carriages, outstretched horses, and mangled bodies ; while disease, sad attendant on military suffering, sweeps

thousands from the great hospitals of the army,

and the multitude of amputated limbs, which there

is no time to destroy, accumulate in bloody heaps,

filling the air with corruption. What tongue, what

pen, can describe the bloody havoc at Borodino,

where, between rise and set of a single sun, more

than one hundred thousand of our fellow-men, equaling in number the population

of this whole city, sank to earth, dead or

wounded? Fifty days after the battle, no less

than twenty thousand are found, stretched where

they gasped out their breath, and the whole

plain is strewn with half-buried carcasses of men and horses, intermingled with garments

dyed in blood, and bones gnawed by dogs and vultures. Who can follow the French army, in dismal

retreat, avoiding the spear of the pursuing Cossack,

only to sink beneath the sharper frost and ice, in

a temperature below zero, on foot, without shelter for the body, famishing on horse-flesh and a

miserable compound of rye and snow-water ? With

a fresh array, the war is continued against new

forces under the walls of Dresden ; and as the

emperor after indulging in royal supper with the

king of Saxony rides over the field of battle, he

sees ghastly new-made graves, with hands and arms

projecting, stark and stiff, above the earth. And

shortly afterwards, when shelter is needed for the

troops, the order is given to occupy the Hospitals

for the Insane, saying, " turn out the mad."

WAR ILLUSTRATED BY SIEGE OF GENOA

Why follow further in this career of blood?

There is one other picture of the atrocious, though

natural consequences of War, occurring almost

within our own day, that I would not omit. Let

me bring to your mind Genoa, called the Superb,

City of palaces, dear to the memory of American

childhood as the birthplace of Christopher Columbus, and one of the spots first enlightened by the

morning beams of civilization, whose merchants

were princes, and whose rich argosies, in those

early days, introduced to Europe the choicest

products of the East, the linen of Egypt, the

spices of Arabia, and the silks of Samarcand.

She still sits in queenly pride, as she sat then,

her mural crown studded with towers, her

churches rich with marble floors and rarest pictures, her palaces of ancient doges and admirals yet spared by the hand of Time, her close

streets, thronged by one hundred thousand inhabitants, at the feet of the maritime Alps, as they

descend to the blue and tideless waters of the

Mediterranean Sea, leaning with her back against

their strong mountain-sides, overshadowed by the

foliage of the fig-tree and the olive, while the

orange and the lemon fill with their perfume the

air where reigns perpetual spring. Who can contemplate such a city without delight? Who can

listen to the story of her sorrows without a pang ?

In the last autumn of the last century, the

armies of the French Republic, which had dominated over Italy, were driven from their conquests,

and compelled, with shrunk forces, to seek shelter

under Massena, within the walls of Genoa. After

various efforts by the Austrian general on the

land, aided by a bombardment from the British

fleet in the harbor, to force the strong defences by

assault, the city was invested by a strict blockade.

All communication with the country was cut off,

while the harbor was closed by the ever-wakeful

British watch-dogs of war. Besides the French

troops, within the beleagured and unfortunate city,

were the peaceful unoffending inhabitants, more

than those of Boston in number. Provisions soon

become scarce ; scarcity sharpens into want, till fell

Famine, bringing blindness and madness in her

train, rages like an Erinnys. Picture to yourself

this large population, not pouring out their lives in

the exulting rush of battle, but wasting at noonday,

the daughter by the side of the mother, the husband

by the side of the wife. When grain and rice fail,

flaxseed, millet, cocoas, and almonds are ground by

handmills into flour, and even bran, baked with

honey, is eaten not to satisfy, but to deaden hunger.

During the siege, but before the last extremities, a

pound of horse-flesh is sold for thirty-two cents ; a

pound of bran for thirty cents ; a pound of flour

for $1.75. A single bean is soon sold for four

cents, and a biscuit of three ounces for $2.25, and

none are finally to be had. The wretched soldiers,

after devouring all the horses, are reduced to the

degradation of feeding on dogs, cats, rats, and

worms, which are eagerly hunted in the cellars and

common sewers. Happy were now, exclaims an

Italian historian, not those who lived, but those

who died ! The day is dreary from hunger ; the

night more dreary still, from hunger accompanied

by delirious fancies. Recourse is had to herbs,

monk's rhubarb, sorrel, mallows, wild succory.

People of every condition, women of noble birth

and beauty, seek on the slope of the mountain

within the defences, those aliments which nature

destined solely for the beasts. A scrap of cheese

and scanty vegetables are all that can be afforded

to the sick and wounded, those sacred stipendiaries

of human charity. Men and women, in the last

anguish of despair, fill the air with groans and

shrieks ; some in spasms, convulsions, and contortions, gasping their expiring breath on the unpitying stones of the streets ; alas ! not more unpitying

than man. Children, whom a dying mother's arms

had ceased to protect, the orphans of an hour,

with piercing cries, seek in vain the compassion of

the passing stranger ; but none pity or aid. The

sweet fountains of sympathy are all closed by the

selfishness of individual distress. In the general

agony, some precipitate themselves into the sea,

while the more impetuous rush from the gates, and

impale their bodies on the Austrian bayonets.

Others still (pardon the dire recital !) are driven

to devour their shoes and the leather of their

pouches ; and the horror of human flesh so far

abates, that numbers feed like cannibals on the

corpses about them.*

*This account has been drawn from the animated sketches

of Botta (History of Italy, under Napoleon, vol. i. cap. i.), Alison (History of French Rev., vol. iv. cap. xxx.), and Arnold

(Modem History, lee. iv.). The humanity of the latter is particularly aroused to

condemn this most atrocious murder of innocent

people, and he suggests, as a sufficient remedy,

a modification of the Laws of War, permitting all non-combatants to

withdraw from a blockaded town ! In this way, they may be

spared a languishing death by starvation ; but they must desert

firesides, pursuits, all that makes life dear, and become homeless

exiles, a fate little better than the former. It is strange that

Arnold's pure soul and clear judgment did not recognize the

truth, that the whole custom or institution of War is unrighteous

and unlawful, and that the horrors of this siege are its natural

consequence. Laws of War ! Laws in what is lawless ! rules of

wrong! There can be only one law of War; that is the great

law, which pronounces it unwise, unchristian, and unjust.

At this stage, the French general capitulated,

claiming and receiving what are called " the honors

of War ; " but not before twenty thousand innocent

persons, old and young, women and children, having

no part or interest in the contest, had died the most

horrible of deaths. The Austrian flag floated over

the captured Genoa but a brief span of time ; for

Bonaparte had already descended, like an eagle

from the Alps, and in less than a fortnight afterwards, on the plains of Marengo, shattered, as

with an iron mace, the Austrian empire in Italy.

DESOLATE HOMES

But wasted lands, famished cities, and slaughtered armies are only a part of " the purple testament

of bleeding war." Every soldier is connected

with others, as all of you, by dear ties of

kindred, love, and friendship. He has been

sternly summoned from the embrace of family. To him, there

is, perhaps, an aged mother, who has fondly hoped

to lean her decaying frame upon his more youthful

form; perhaps a wife, whose life has been just

entwined inseparably with his, now condemned to

wasting despair ; perhaps sisters, brothers. As he

falls on the field of war, must not all these rush with

his blood ? But who can measure the distress that

radiates as from a bloody sun, penetrating innumerable homes? Who can give the

gauge and dimensions of this incalculable

sorrow? Tell me, ye who feel the bitterness of

parting with dear friends -and kindred, whom you

watch tenderly till the last golden sands are

run out and the great hour-glass is turned, what

is the measure of your anguish? Your friend

departs, soothed by kindness and in the arms of Love ; the soldier gasps

out his life with no friend near, while the scowl of

Hate darkens all that he beholds, darkens his own

departing soul. Who can forget the anguish that

fills the bosom and crazes the brain of Leonora, in

the matchless ballad of Burger, when seeking in

vain among returning squadrons for her lover left

dead on Prague's ensanguined plain? But every

field of blood has many Leonoras. Every war has

its desolate homes, as is most vividly pictured by

a master poet of antiquity, whose verse is an argument.*

* Agamemnon of AEschylus

; Chorus. This is from the beautiful translation by John Symmons.

But through the bounds of Grecia's land,

Who sent her sons for Troy to part,

See mourning, with much suffering heart,

On each man's threshold stand,

On each sad hearth in Grecia's land. Well may her soul with grief be rent; She

well remembers whom she sent, She sees them

not return ;

Instead of men, to each man's home,

Urns and ashes only come,

And the armor which they wore ;

Sad relics to their native shore.

For Mars, the barterer of the lifeless clay,

Who sells for gold the slain,

And holds the scale in battle's doubtful day,

High balanced o'er the plain,

From Ilium's walls for men returns

Ashes and sepulchral urns ;

Ashes wet with many a tear,

Sad relics of the fiery bier.

Round the full urns the general groan

Goes, as each their kindred own.

One they mourn in battle strong,

And one, that 'mid the armed throng

He sunk in glory's slaughtering tide,

And for another's consort died.

******

Others they mourn whose monuments stand

By Ilium's wall on foreign strand ;

"Where they fell, in beauty's bloom,

There they lie in hated tomb ;

Sunk beneath the massy mound,

In eternal chambers bound.

WAR INEFFECTUAL TO ESTABLISH JUSTICE

III. But all these

miseries are to no purpose. War is utterly

ineffectual to secure or advance the object

which it professes to seek. The wretchedness which it entails, contributes to no end, helps

to establish no right, and, therefore, in no respect

determines justice between the contending nations.

The fruitlessness and vanity of War appear in

the great conflicts by which the world has been

lacerated. After long struggle, where each nation

inflicts and receives incalculable injury, peace has

been gladly obtained on the basis of the condition

before the War, known as the Status ante Bellum.

I cannot better illustrate this point, than by the

familiar example humiliating to both countries

of the last war with Great Britain, the professed

object of which was to obtain from the latter Power

a renunciation of her insolent claim to impress

our seamen. The greatest number of American

seamen officially alleged to be compulsorily serving

in the British navy was about eight hundred. To

overturn this injustice, the Arbitrament of War

was invoked, and the whole country was doomed

for more than three years to its accursed blight.

American commerce was driven from the seas ;

the resources of the land were drained by taxation ; villages on the Canadian

frontier were laid in ashes ; the metropolis of

the Republic was captured, while gaunt distress raged everywhere within

our borders. Weary at last with this rude Trial,

our Government appointed Commissioners to treat

for Peace, with these specific instructions: "Your

first duty will be to conclude peace with Great

Britain ; and you are authorized to do it, in case

you obtain a satisfactory stipulation against

impressment, one which shall

secure under our flag protection to the crew. If

this encroachment of Great Britain is hot

provided against, the United States have

appealed to arms ! in vain" *

impressment, one which shall

secure under our flag protection to the crew. If

this encroachment of Great Britain is hot

provided against, the United States have

appealed to arms ! in vain" *

* American State

Papers, vol. vii. p. 577.

Afterwards, finding small chance of extorting

from Great Britain a relinquishment of the

unrighteous claim, and foreseeing only an

accumulation of calamities from an inveterate prosecution of the War,

our Government directed their negotiators, in concluding a treaty of Peace, " to omit any stipulation

on the subject of impressment" The instructions

were obeyed, and the Treaty that once more restored to us the blessings of Peace, so rashly cast

away, but now hailed with an intoxication of joy,

contained no allusion to impressment, nor did it

provide for the surrender of a single American

sailor detained in the British navy. Thus, by the

confession of our own Government, " the United

States had appealed to arms IN VAIN. "

All this is the natural result of an appeal to War,

in order to establish justice. Justice implies the

exercise of the judgment in the determination of

right. Now War not only supersedes the judgment,

but delivers over the pending question to superiority

of force, or to chance.

Superior Force may end in conquest ; this is its

natural consequence ; but it cannot adjudicate any

right. We expose the absurdity of its Arbitrament, when, by a familiar phrase of sarcasm, we

speak of the right of the strongest excluding, of

course, all idea of right, except that of the lion, as

he springs upon a weaker beast ; of the wolf, as he

tears in pieces the lamb ; of the vulture, as he

fattens upon the dove. The grossest spirits will

admit that this is not justice.

But the battle is not always to the strong. Superiority

of Force is often checked by the proverbial

contingencies of War. Especially are such contingencies

revealed in rankest absurdity, where nations, as

is their acknowledged custom, without regard to

their respective forces, whether weaker or

stronger, voluntarily appeal to this mad Umpirage. Who can measure beforehand the currents

of the heady fight? In common language, we speak

of the chances of battle ; and soldiers whose lives

are devoted to this harsh vocation, yet call it a

game. The Great Captain of our age, who seemed

to drag victory at his chariot-wheels, in a formal

address to his officers, on entering Russia, says,

" In war, fortune has an equal share with ability

in procuring success." *

* Alison, VIII.

346.

The famous victory of

Marengo, accident of an accident, wrested unexpectedly at the close of the day from a foe, who

at an earlier hour was successful, taught him the

uncertainty of War. Afterwards, in bitterness of

spirit, when his immense forces had been shivered,

and his triumphant eagles driven back with broken

wing, he exclaimed, in that remarkable conversation recorded by the Abbee de Pradt : " Well, this

is War. High in the morning, low enough at

night. From a triumph to a fall, is often but a

step." *

* Ib. IX. 239.

The same sentiment is repeated by the

military historian of the Peninsular campaigns,

when he says : " Fortune always asserts her supremacy in War ; and often

from a slight mistake, such disastrous

consequences flow, that, in every age and in

every nation, the uncertainty of wars has been

proverbial ; " *

* J Napier,

IV. 687.

and again, in

another place, considering the conduct of

Wellington, the same military historian, who is

an unquestionable authority, confesses : " A few hours' delay, an accident, a turn of fortune, and he would have been

foiled ! Ay ! but this is War, always dangerous and uncertain, an ever-rolling wheel, and armed

with scythes." *

* Napier IV 477.

And can intelligent man look for

justice to an ever-rolling wheel armed with scythes?

Chance is written on every battlefield. It may

be discerned less in the conflict of large masses,

than in that of individuals, though equally present

in each. How capriciously the wheel turned when

the fortunes of Rome were staked on the combat

between the Horatii and Curiatii ! and who, at

one time, could have augured that the single Horatius, with two slain brothers

on the field, would overpower the three living

enemies? But this is not alone. In all the

combats of history, involving the fate of

individuals or nations, we learn to revolt at

the frenzy which carried questions of property,

of freedom, or of life, to a judgment so

uncertain and senseless.

THE TRIAL BY BATTLE

During the early

modern centuries, and especially in the moral

night of the dark ages, the practice extensively

prevailed throughout Europe, of submitting controversies, whether of individuals or

communities, to this adjudication. I pass over the

custom of Private War, though it aptly illustrates

the subject, stopping merely to join in that delight,

which, at a time of ignorance, before this mode

of determining justice had gradually yielded to the

ordinances of monarchs and an advancing civilization, hailed its temporary suspension, as

The Truce of God; and I come at once to the Judicial

Combat, or TRIAL BY BATTLE. In this custom, or

institution, as in a mirror, we may behold the

hideousness of War.

Trial by Battle

was a formal and legitimate mode of deciding

controversies, principally between individuals. Like other ordeals, by burning plough-shares, by holding hot iron, by dipping the hand in

hot water or hot oil and like the great Ordeal of

War it was a presumptuous appeal to Providence, under an apprehension and hope, that

Heaven would give the victory to him who had the

right. Its object was precisely the professed object

of War, the determination of Justice. It was sanctioned by Municipal Law as an Arbitrament

for individuals ; as War to the scandal of civilization

is still sanctioned by International Law, as an

Arbitrament for nations. Men, says the brilliant

Frenchman, Montesquieu, subject to rules even

their prejudices ; and Trial by Battle was surrounded by artificial regulations of multifarious

detail, constituting an extensive system, determining how and when it should be waged ; as War is

surrounded by a complex code, known as the Laws

of War.

No question was too sacred, grave, or recondite

for this Tribunal. The title of an abbey to a neighboring church, in France, was decided by it ; and

an emperor of Germany, according to a faithful

ecclesiastic, " desirous of dealing honorably with

his people and nobles " (mark here the standard of

honor !), waived the judgment of the court on a

grave question of law, as to the descent of property,

and referred it to champions. Human folly did not

stop here. In Spain, a subtle point of theology

was submitted to the same determination. But

Trial by Battle was not confined to particular countries or to rare occasions.

It prevailed everywhere in Europe, superseding

in many places all other ordeals and even trials

by proofs, and extending not only to criminal

matters, but to questions of property. Like War in our day, its justice and fitness

as an Arbitrament were early doubted or condemned. Luitprand, a king of the Lombards,

in Italy, during that middle period which

belongs neither to ancient nor to modern times,

in a law bearing date 713, expresses his

distrust of it as a mode of determining justice

; but the monarch is compelled to add that,

considering the custom of his Lombard people, he

cannot forbid the impious law. His words deserve

emphatic mention : Propter consuetudinem gentis nostrse Longobardorum legem impiam vetare nonpossumus.*

* Muratori, Rerum

Italic. Script, t. 2, p. 65.

The appropriate epithet

by which he branded Trial by Battle is the important bequest of the royal Lombard to a distant

posterity. For this, the name of the lawgiver

will be cherished, with grateful regard, in the

annals of civilization.

This custom received another blow from Rome.

At the latter part of the thirteenth century, Don Pedro of Aragon, after

exchanging letters of defiance with Charles of

Anjou, proposed to the latter a personal combat,

which was accepted, on condition that Sicily

should be the prize of success.*

*Sismondi,

Histoire des Fran9, VIII. 338-340.

Each called down upon himself all the

vengeance of Heaven, and the last dishonor, if, at

the appointed time, he failed to appear before the

Seneschal of Aquitaine, or, in case of defeat, if

he refused to consign Sicily undisturbed to the

victor. While the two champions were preparing

for the .lists, the pope, Martin IV., protested with

all his power against this new Trial by Battle,

which staked the sovereignty of a kingdom, a feudatory of the Holy See, on a wild stroke of chance.

By a papal bull, dated at Civita Vecchia, April 5th,

1283, he threatened excommunication to either of

the princes, who proceeded to a combat which he

pronounced criminal and abominable. By a letter

of the same date, the Pope announced to Edward I.

of England, Duke of Aquitaine, the agreement of

the two princes, which he most earnestly declared

to be full of indecency and rashness, hostile to the

concord of Christendom, and careless of Christian

blood ; and he urged upon the English monarch to

spare no effort to prevent the combat menacing

him with excommunication, and his territories

with interdict, if it should take place. Edward refusing to guarantee the safety of the combatants in

Aquitaine, the parties retired without consummating their duel. The judgment of the Holy See,

which thus accomplished its immediate object,

though not in terms directed to the suppression of

the custom of Trial by Battle, remains, nevertheless, from its peculiar energy

of language, in perpetual testimony against it.

ST. LOUIS ABOLISHES TRIAL BY BATTLE IN FRANCE

To a monarch of

France belongs the honor of first interposing

the royal authority, for the entire suppression

within his jurisdiction, of this impious custom,

so universally adopted, so dear to the nobility,

and so profoundly rooted in the institutions of

the Feudal Age. And here let me pause with

reverence, as I mention the name of St. Louis, a

prince, whose unenlightened errors may find easy

condemnation in an age of larger toleration and

wider knowledge, but whose firm and upright

soul, whose exalted sense of justice, whose

fatherly regard for the happiness of his people, whose respect

for the rights of others, whose conscience, void of

offence before God and man, make him foremost

among Christian rulers, and the highest example

for a Christian prince or a Christian people, in

one word, a model of True Greatness. He was of

angelic conscience, subjecting all that he did to the

single and exclusive test of moral rectitude, disregarding every consideration of worldly advantage,

every fear of worldly consequence.

His soul, thus

tremblingly sensitive to questions of right, was

shocked by the judicial combat. It was a sin, in

his sight, thus to tempt God, by demanding of

him a miracle, whenever judgment was pronounced.

From these intimate convictions sprung a royal

Ordinance, first promulgated at a Parliament

assembled in 1260:

"We forbid to

all persons throughout our dominions the

TRIAL BY BATTLE ; and instead of battles, we establish proofs by

witnesses; and we do not take away the other good

and loyal proofs which have been used in lay courts

to this day.

* * *

AND THESE BATTLES

WE ABOLISH IN OUR DOMINIONS FOREVER." *

* Guizot, Histoire

de la Civilization en France, IV. 162-164.

Such were the restraints on the royal authority,

that this Ordinance did not extend to the

demesnes of the barons and feudatories of the

realm, being confined in its operation to those

of the king. But where the power of the

sovereign did not reach, there he labored by

example, influence, and express intercession ;

treating with many of the great vassals, and

inducing them to renounce this unnatural usage.

Though for many years later it vexed some parts

of France, its overthrow commenced with the

Ordinance of St. Louis.

Honor and

blessings attend the name of this truly

Christian king; who submitted all his actions to

the Heaven-descended sentiment of duty ; who began a long and illustrious reign, by renouncing and

restoring a portion of the conquests of his predecessor, saying to those about him, whose souls did not

ascend to the height of his morality, " I know that

the predecessors of the king of England have lost

by the right of conquest the land which I hold ;

and the land which I give him, I do not give because I am bound to him or his heirs, but to put

love between my children and his children, who are

cousins-german; and it seems to me that what I

thus give, I employ to good purpose ! " *

* I b. IV. 151.

Honor

to him who never grasped by force or cunning any

new acquisition ; who never sought advantage from the turmoil and dissension of his neighbors, but

studied to allay them ; who, first of Christian

Princes, rebuked the Spirit of War, saying to those

who would have him profit by the strifes of others, "Blessed are the

Peacemakers;" * who, by an immortal Ordinance,

abolished Trial by Battle throughout his

dominions ; who executed equal justice to all,

whether his own people, or neighbors, and in the

extremity of his last illness on the sickening

sands of Tunis, among the bequests of his

spirit, enjoined on his son and successor, " in

maintaining justice, to be inflexible and loyal,

turning neither to the right hand nor to the

left ! " **

* Benoist soient tuit li apaiseur.

Joinville, p. 143.

** Sismondi, Histoire des France. VIII. 196.

TRIAL BY BATTLE ABOLISHED IN ENGLAND

To condemn Trial by Battle, no longer requires

the sagacity above his age of the Lombard monarch, or the intrepid judgment of the Sovereign

Pontiff, or the ecstatic soul of St. Louis. An incident of history, as curious

as it is authentic, illustrates this point, and shows the certain progress of

opinion. This custom, as a part of the common

law of England, was partially restrained by Henry

II., and rebuked at a later day by Elizabeth.

Though fallen into desuetude, quietly overruled by

the enlightened sense of successive generations, yet,

to the disgrace of English jurisprudence, it was not

legislatively abolished till almost in our own day,

as late as 1817, when the right to it was

openly claimed in Westminster Hall. An ignorant

man charged with murder, whose name, Abraham

Thornton, is necessarily connected with the

history of this monstrous usage, being proceeded

against by the ancient process of appeal,

pleaded, when brought into court, as follows : "

Not guilty, and I am ready to defend the same by

my body ; " and thereupon taking off his glove,

he threw it upon the floor. The appellant not

choosing to accept this challenge, abandoned his

proceedings. The bench, the bar, and the whole

kingdom were startled by the outrage ; and at

the next session of parliament, Trial by Battle

was abolished in England. On introducing a bill for this purpose, the Attorney-General remarked, in appropriate terms, that "if

the party had persevered, he had no doubt the

legislature would have felt it their imperious duty

to interfere, and pass an ex post facto law to prevent

so degrading a spectacle from taking place."*

* Annual Register,

vol. Ixi. p. 52 (1819) ; Blackstone, Com. Ill

337, Chitty's note.

These words aptly portray the impression which

Trial by Battle excites in our day. Its folly

and wickedness are apparent to all. As we revert

to those early periods in which it prevailed,

our minds are impressed by the general barbarism

; we recoil with horror from the awful

subjection of justice to brute force ; from the

impious profanation of God in deeming him

present at these outrages ; from the moral

degradation out of which they sprang, and which

they perpetuated ; we involve ourselves in

self-complacent virtue, and thank God that we

are not as these men, that ours is an age of light,

while theirs was an age of darkness !

ONE AND THE SAME LAW OF RIGHT FOR NATIONS

AND INDIVIDUALS

But do not forget, fellow-citizens, that this criminal and impious custom, which we all condemn in

the case of individuals, is openly avowed by our

i own country, and by the other countries of the 'great Christian Federation

nay, that it is expressly established by International Law as the

proper mode of determining justice between nations ; while the feats of

hardihood by which it is waged, and the triumphs

of its fields, are exalted beyond all other

labors, whether of learning, industry, or benevolence, as a well-spring of Glory.

Alas ! upon our own heads be the judgment of

barbarism, which we pronounce upon those that

have gone before ! At this moment, in this period

of light, while to the contented souls of many the

noonday sun of civilization seems to be standing

still in the heavens, as upon Gibeon, the relations

between nations continue to be governed by the

odious rules of brute violence, which once predominated between individuals. The

dark ages have not yet passed away ; Erebus and

black Night, born of Chaos, still brood over the

earth ; nor can we hail the clear day, until the

hearts of the nations are touched, as the hearts

of individual men, and all acknowledge one

and the same Law of Right.

Who has told you,

fond man ! thus to find Glory in an act when

performed by a nation which you condemn as a

crime or a barbarism when committed by an

individual ? In what vain conceit of wisdom and

virtue do you find this incongruous morality?

Where is it declared that God, who is no

respecter of persons, is a respecter of multitudes ? Whence do you draw these partial laws of

a powerful and impartial God ? Man is immortal ;

but States are mortal. He has a higher destiny

than States. Can States be less amenable to

the supreme moral law ? Each individual is an

atom of the mass. Must not the mass, in its conscience, be like the individuals of which it is composed? Shall the mass, in relations with other

masses, do what individuals in relations with each

other may not do? As in the physical creation, so

in the moral, there is but one rule for individuals

and masses. It was the lofty discovery of Newton,

that the simple law, which determines the fall of an

apple, prevails everywhere throughout the Universe

ruling each particle in reference to every other

particle, whether large or small reaching from

earth to heaven, and controlling the infinite motions

of the spheres ; so, with equal scope, another simple law, the Law of Right, which binds the individual, binds also two or three when gathered

together ; binds conventions and congregations of

men ; binds villages, towns, and cities ; binds

states, nations, and empires ; clasps the whole

human family in its sevenfold embrace ; nay, more,

Beyond the flaming bounds of place and time,

The living throne, the sapphire blaze,

it binds the

angels of Heaven, the Seraphim, full of love,

the Cherubim, full of knowledge ; above all, it

binds, in self-imposed bonds, a just and omnipotent

God. This is the law, of Which the ancient poet

sings, as Queen alike of mortals and immortals. It

is of this, and not of any earthly law, that Hooker

speaks in that magnificent period which sounds

like an anthem ; "Of law, no less can be said,

than that her seat is the bosom of God, her voice

the harmony of the world ; all things in Heaven

and earth do her homage, the very least as feeling

her care, the greatest as not exempted from her

power ; both angels and men, and creatures of

what condition soever, though each in different

sort and manner, yet all with uniform consent admiring her as the mother of their peace and joy."

Often quoted, and justly admired, sometimes as the

finest sentence of our English speech, this grand

declaration cannot be more justly invoked than to

condemn the pretension of one law for individuals

and another for nations.

Stripped of all delusive apologies, and tried by

that comprehensive law under which nations are

set to the bar like common men "War falls from Glory into barbarous guilt. It takes its place among

bloody transgressions, while its flaming honors are

turned into shame. Painful to existing prejudices

as it may be, we must learn to abhor it, as we

abhor similar transgressions by a vulgar offender.

Every word of reprobation, which the enlightened

conscience now fastens upon the savage combatant

in Trial by Battle, or which it applies to the unhappy being, who, in murderous duel, takes the

life of his fellow-man, belongs also to the nation

that appeals to War. Amidst the thunders which

made Sinai tremble, God declared, " Thou shalt not

kill ; " and the voice of these thunders, with this

commandment, has been prolonged to our own

day in the echoes of Christian churches. What

mortal shall restrain the application of these

words? Who on earth is empowered to vary or

abridge the commandments of God? Who shall

presume to declare, that this injunction was directed, not to nations, but to individuals only ;

not to many, but to one only ; that one man may

not kill, but that many may ; that one man may

not slay in duel, but that a nation may slay a

multitude in the duel of war ; that it is forbidden

to each individual to destroy the life of a single

human being, but that it is not forbidden to a

nation to cut off by the sword a whole people ?

We are struck with horror and our hair stands on

end at the report of a single murder ; we think of

the soul that has been hurried to its final account ;

we seek the murderer ; and the State puts forth all

its energies to secure his punishment. Viewed in

the unclouded light of truth, what is War but

organized murder ; murder of malice aforethought ;

in cold blood ; under the sanctions of an impious

law; through the operation of an extensive machinery of crime ; with innumerable hands ; at incalculable cost of money; by subtle contrivances

of cunning and skill ; or amidst the fiendish atrocities of the savage brutal assault ?

The Scythian,

undisturbed by the illusion of military Glory,

snatched a phrase of justice from an

acknowledged criminal, when he called Alexander " the greatest robber in the world." And

the Roman satirist, filled with similar truth,

in pungent words, touched to the quick that

flagrant unblushing injustice which dooms to

condign punishment the very guilt, that in another sphere, and

on a grander scale, under the auspices of a nation,

is hailed with acclamation.

Ille crucem sceleris pretium tulit, hie diadema.*

* Juvenal, lat.

xiii. 105.

Mankind, blind to the real character of War, while

condemning the ordinary malefactor, may continue

yet a little longer to crown its giant actors with

Glory. A generous posterity may pardon to unconscious barbarism the atrocities which they have

waged ; but the whole custom and it is of this

that I speak though sanctioned by existing law,

cannot escape the unerring judgment of reason and

religion. The outrages which, under solemn sanctions of law, it permits and invokes for professed

purposes of justice, cannot be authorized by any

human power ; and they must rise in overwhelming

judgment, not only against those who wield the

weapons of Battle, but more still against all who

uphold its monstrous Arbitrament.

THE ST. LOUIS OF THE NATIONS

When, oh ! when shall the St. Louis of the

Nations arise the Christian ruler, or Christian

people, who, in the spirit of True Greatness, shall

proclaim, that henceforward forever the great Trial

by Battle shall cease; that "these battles" shall

be abolished throughout the Commonwealth of civilization ; that a spectacle so degrading shall

never

be allowed again to take place ; and that it is the

duty of Nations, involving of course the highest

policy, to establish love between each other, and, in

all respects, at all times, with all persons, whether

their own people or the people of other lands, to be

governed by the sacred Law of Right, as between

man and man. May God speed the coming of that

day !

OBSTACLES

I have already alluded, in the early part of this

Address, to some of the obstacles encountered by

the advocate of Peace. One of these is the war-like tone of the literature, by which our minds are

formed. The world has supped so full with battles,

that all its inner modes of thought, and many of

its rules of conduct, seem to be incarnadined with

blood ; as the bones of swine, fed on madder, are

said to become red. But I now pass this by,

though a fruitful theme, and hasten to other topics.

I propose to consider in succession, very briefly,

some of those prejudices, which are most powerful

in keeping alive the custom of War.

BELIEF THAT WAR IS A NECESSITY

1. One of the most important is the prejudice

founded on a belief in its necessity. When War is