|

The True Grandeur of Nations

Go here for more about

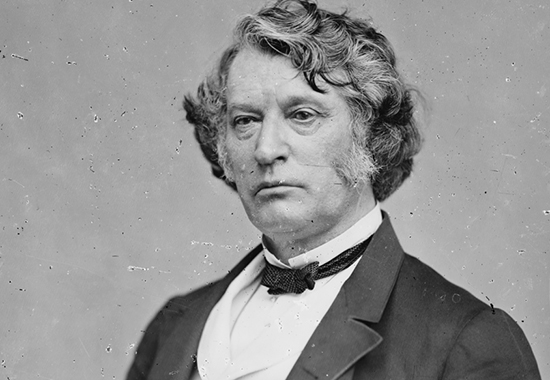

Charles Sumner.

Charles Sumner.

Go here for more about

Charles Sumner's Grandeur of Nations

speech.

Charles Sumner's Grandeur of Nations

speech.

It follows the full text transcript of

Charles Sumner's The True Grandeur of Nations

speech, delivered before the authorities of the city of

Boston on July 4, 1845.

This is page 2 of

2 of Sumner's speech.

Go to page 1.

Go to page 1.

And this benign sentiment commends itself, alike

to the Christian who is told to render good for

evil, and to the universal heart of man. But who

that confesses its truth can vindicate a resort

to force, for the sake of honor?

It seems that in

ancient Athens, as in unchristianized Christian

lands, there were sophists who urged that to

suffer was unbecoming a man, and would draw down

incalculable evil. The following passage, which

I translate with scrupulous literalness, will

show the manner in which the moral cowardice of

these persons of little faith was rebuked by

him, whom the gods pronounced wisest of men : "These things being so, let us inquire what it is

you reproach me with ; whether it is well said,

or not, that I, forsooth, am not able to

assist either myself, or any of my friends or my

relations, or to save them from the greatest

dangers, but that, like the outlaws, I am at the

mercy of any one, who may choose to smite me on

the temple and this was the strong point in your

argument or take away my property, or drive me

out of the city, or (to take the extreme case)

kill me ; now, according to your argument, to be

so situated is the most shameful thing of all. But my view

is, a view many times expressed already, but there

is no objection to its being stated again, my view,

I say, is, O Callicles, that to be struck unjustly on the temple is not most

shameful, nor to have my body

mutilated, nor my purse cut; but to strike me and

mine unjustly, and to mutilate me and to cut my

purse is more shameful and worse ; and stealing, too,

and enslaving, and housebreaking, and in general,

doing any wrong whatever to me and mine, is more

shameful and worse for him who does the wrong, than

for me who suffer it. These things thus established

in the former arguments, as I maintain, are secured

and bound, even if the expression be somewhat

too rustical, with iron and adamantine arguments, and unless you, or someone

more vigorous than you, can break them, it is

impossible for any one, speaking otherwise than I now' speak, to speak well:

since, for my part, I always have the same thing to say,

that I know not how these things are, but that of all

whom I have ever discoursed with as now, not one is

able to say otherwise without being ridiculous"*

* Gorgias, cap.

lxiv.

Such

is the wisdom of Socrates, as reported by Plato ; and

it has found beautiful expression in the verse of an

English poet, who says :

Dear as freedom is, and in my heart's just

Esteem prized above all price, myself

Had rather be the slave, and wear the chains,

Than fasten them on him.

The modern point of honor did not obtain a place

in warlike antiquity. Themistocles at Salamis

did not send a cartel to the Spartan commander,

when threatened by a blow. " Strike, but hear,"

was the response of that firm nature, which felt

that True Honor was gained only in the

performance of duty. It was in the depths of

modern barbarism, in the age of chivalry, that

this sentiment shot up in the wildest and most

exuberant fancies. Not a step was taken without

reference to it. No act was done which had not

some point tending to the " bewitching duel."

And every stage in the combat, from the

ceremonial of its beginning, to its deadly

close, was measured by this fantastic law.

Nobody can forget the humorous picture of the

progress of quarrel to a duel, through the seven

degrees of Touchstone, in As You Like It. But

the degradation, in which the law of honor has

its origin, may be illustrated by an authentic

incident from the life of its most brilliant

representative. The Chevalier Bayard, the

cynosure of chivalry, the knight without fear

and without reproach, in a contest with the Spaniard Don Alonzo

de Soto Mayor, by a feint struck him such a blow in

the throat, that the weapon, despite the gorget, penetrated four fingers deep. The wounded Spaniard

gasped and struggled until they both rolled on the

ground, when Bayard, drawing his dagger, and

thrusting its point in the nostrils of his foe, exclaimed, " Senor Don Alonzo, surrender, or you are

a dead man ; " a speech which appeared superfluous,

as the second of the Spaniard cried out, " Senor

Bayard, he is dead ; you have conquered." The

French knight would have given one hundred thousand crowns for the opportunity to spare that life ;

but he now fell upon his knees, kissed the ground

three times, and then dragged his dead enemy out of

the camp, saying to the second, " Senor Don Diego,

have I done enough ? " To which, the other piteously

replied, " Too much, senor, for the honor of Spain ! "

when Bayard very generously presented him with

the corpse, although it was his right, by the law of

honor, to dispose of it as he thought proper ; an act

which is highly commended by the chivalrous Brantome, who thinks it difficult to say which did most

honor to the faultless knight not dragging the

body ignominiously by a leg out of the field, like the

carcass of a dog, or condescending to fight while

laboring under an ague !

If such a transaction conferred honor on the

brightest son of chivalry, we may understand from

it something of the real character of an age, the

departure of which has been lamented with such

touching but inappropriate eloquence. Do not condescend to draw a comprehensive rule of conduct

from a period like this. Let the fanaticism of

honor stay with the daggers, swords, and weapons

of combat by which it was guarded ; let it appear

only with its inseparable American companions, the

bowie-knife and the pistol !

I would that our standard of conduct were derived, not from the degradation of our nature,

though it affect the semblance of sensibility and

refinement, but from the loftiest attributes of man,

from truth, from justice, from duty; and may this

standard, while governing our relations to each

other, be recognized also among the nations ! Alas ! when shall we behold the

dawning of that happy day, harbinger of infinite

happiness beyond, in which nations, like

individuals, shall feel that it is better to

receive a wrong than to do a wrong.

Apply this

principle to our relations at this moment with England. Suppose that proud monarchy,

refusing all submission to Negotiation or Arbitration, should absorb the whole territory of Oregon

into her own overgrown dominions, and add, at the

mouth of the Columbia River, a new morning drumbeat to the national airs with which she has encircled

the earth ; who, then, is in the attitude of Truest

Honor, England appropriating, by an unjust act,

what is not her own, or the United States, the

victim of the injustice?

A FALSE PATRIOTISM

5. There is still another influence which stimulates War, and interferes with the natural attractions

of Peace ; I refer to a selfish and exaggerated prejudice of country, leading to

its physical aggrandizement, and political

exaltation, at the expense of other countries,

and in disregard of justice. Nursed by the

literature of antiquity, we have imbibed the

narrow sentiment of heathen patriotism.

Exclusive love for the land of birth was a part

of the religion of Greece and Rome. It is an

indication of the lowness of their moral nature,

that this sentiment was so material as well as

exclusive in character. The Oracle directed the

returning Roman to kiss his mother, and he

kissed the Mother Earth. Agamemnon, according to

AEschylus, on regaining his

home, after a perilous separation of more than ten

years, at the siege of Troy, before addressing family,

friend, or countryman, salutes Argos :

By your leave, lords, first Argos I salute.

The schoolboy cannot forget the cry of the victim

of Verres, which was to stay the descending fasces

of the lictor, " I am a Roman citizen ; " nor those

other words echoing through the dark Past, " How

sweet to die for country ! " Of little avail that

nobler cry, " I am a man ; " or that Christian ejaculation, swelling the soul, " How sweet to die for

duty ! " The beautiful genius of Cicero, at times

instinct with truth almost divine, did not ascend to

that highest heaven, where is taught, that all mankind are neighbors and kindred, and that the relations of fellow-countryman are less holy than those

of fellow-man. To the love of universal man may

be applied those words by which the great Roman

elevated his selfish patriotism to a virtue when he

said, that country alone embraced all the charities of

all. *

* De Offic. Lib. 1, cap. xvii. It is curious to observe how Cicero

puts aside that expression of true Humanity, which fell from

Terence, Humani nikila me alienum puto. He says, Est enim

difficilis cura rerum alienarum. De Offic. Lib. 1, cap. ix.

Attach this admired phrase to the single idea

of country, and you will see how contracted are its

charities, compared with that world-wide circle in

which our neighbor is the suffering man, though at

the farthest pole. Such a sentiment would dry up

those fountains, whose precious waters now diffuse

themselves in distant unenlightened lands, bearing

the blessings of truth to the icy mountains of Greenland and the coral islands of the Pacific sea.

It has been a part

of the policy of rulers to encourage this

exclusive patriotism ; and the people of modern

times have all been quickened by the feeling of

antiquity. I do not know that any one nation is

in a condition to reproach another with this

patriotic selfishness. All are selfish. Men are

taught to live, not for mankind, but only for a

small portion of mankind. The pride, vanity, ambition,

brutality even, which all rebuke in individuals, are

accounted virtues when displayed in the name of a

country. Among us, the sentiment is active, while

it derives new force from the point with which it has

been expressed. An officer of our Navy, one of the

heroes nurtured by War, whose name has been

praised in churches, going beyond all Greek, all

Roman example, exclaims, " Our country, be she

right or wrong; " a sentiment dethroning God and

enthroning the devil, whose flagitious character

must be rebuked by every honest heart. Unlike

this officer was the virtuous Andrew Fletcher, of Saltoun, in the days of the English Revolution, of

whom it was said, that he " would lose his life to

serve his country, but would not do a base thing

to save it." Better words, or more truly patriotic,

have never been uttered. " Our country, our whole

country, and nothing but our country," are other

words which, falling first from the lips of an eminent

American, have often been painted on banners, and

echoed by the voices of innumerable multitudes.

Cold and dreary, narrow and selfish, would be this

life, if nothing but our country occupied our souls ;

if the thoughts that wander through eternity, if the

infinite affections of our nature, were restrained to

that spot of earth where we have been placed by the

accident of birth.

I do not inculcate indifference to country. We

incline by a natural sentiment to the spot where we

were born, to the fields that witnessed the sports of

childhood, to the seat of youthful studies, and to

the institutions under which we have been trained.

The finger of God

writes all these things indelibly upon the heart

of man, so that in the anxious extremities of death, he reverts in fondness to early

associations, and longs for a draught of cold water

from the bucket in his father's well. This sentiment

is independent of reflection, for it begins before

reflection, grows with our growth, and strengthens

with our strength. It is blind in nature ; and therefore, it is a duty to watch that it does not absorb

and pervert the whole character. In the moral

night which has enveloped the world, nations lived

ignorant and careless of the interests of others,

which they imperfectly saw ; but the thick darkness

is now scattered, and we begin to discern the distant mountain-peaks of other lands, all gilded by

the beams of morning. "We find that God has not

placed us on this earth alone ; that there are others,

equally with us, children of his protecting care.

The curious spirit goes further, and while recognizing an inborn sentiment of attachment to the

place of birth, inquires into the nature of the allegiance due to the State. According to the old idea,

still too much received, man is made for the State,

and not the State for man. Far otherwise is the

truth. The State is an artificial body, intended for

the security of the people. How constantly do we

find, in human history, that the people have been

sacrificed for the State ; to build the Roman name,

to secure for England the trident of the sea. This is

to sacrifice the greater to the less ; for the False

Grandeur of earth, to barter life and the soul itself.

Not that I love country less, but Humanity more,

do I now, on this National Anniversary, plead the

cause of a higher and truer patriotism. I cannot

forget that we are men, by a more sacred bond than

we are citizens ; that we are children of a common

Father more than we are Americans.

Recognizing this truth, the seeming diversities of

nations, separated only by the accident of mountain, river, or sea, all disappear, and the various

people of the globe stand forth as brothers members of one great Human Family. Discord in this

family is treason to God ; while all War is nothing

else than civil war. In vain do we restrain this

odious term, importing so much of horror, to the

petty dissensions of a single nation. It belongs as

justly to the feuds between nations, when referred

to the umpirage of battle. The soul trembles

aghast, as we contemplate fields drenched in fraternal gore, where the happiness of homes has been

shivered by the unfriendly arms of neighbors, and

kinsman has sunk beneath the steel nerved by a

kinsman's hand. This is civil war, which stands

accursed forever in the calendar of time. But the

Muse of History, in the faithful record of the future

transactions of nations, inspired by a loftier justice,

and touched to finer sensibilities, will extend to the

general sorrows of Universal Man the sympathy still

profusely shed for the selfish sorrow of country,

while it pronounces international War to be civil

War, and the partakers in it traitors to God and

enemies to man.

THE GENERAL COST OF WAR

6. I might here pause, feeling that those of my

hearers who have kindly accompanied me to this

stage, would be ready to join in the condemnation

of War, and hail Peace, as the only condition becoming the dignity of human nature. But there is

still one other consideration, which yields to none

of the rest in importance ; perhaps it is more important than all. It is at once cause and effect,

the cause of much of the feeling in favor of War,

and the effect of this feeling. I refer to the costly

PREPARATIONS FOR WAR in time of Peace. And

here is an immense practical evil, requiring an immediate remedy. Too much time cannot be taken

in exposing its character.

I shall not dwell upon the immense cost of War

itself. That will be present to the minds of all, in

the mountainous accumulations of debt, piled like

Ossa upon Pelion, with which Europe is pressed to

the earth. According to the most recent tables to

which I have access, the public debt of the different

European nations, so far as known, amounts to the

terrific sum of $6,387,000,000, all the growth of

War ! It is said that there are throughout these

states, 17,900,000 paupers, or persons subsisting at

the expense of the country, without contributing to

its resources. If these millions of public debt,

forming only a part of what has been wasted in

War, could be apportioned among these poor, it

would give to each, $375, a sum which would place

all above want, and which is about equal to the

average wealth of each inhabitant of Massachusetts.

The public debt of Great Britain reached, in 1839,

to $4,265,000,000, the growth of War since 1688 !

This amount is nearly equal, according to the

calculations of Humboldt, to the sum-total of

all the treasures reaped from the harvest of gold

and silver in the mines of Spanish America,

including Mexico and Peru, since the first discovery of our hemisphere by

Christopher Columbus ! It is much larger than

the mass of all the precious metals, which at

this moment form the circulating medium of the

world ! It is sometimes rashly said by those who

have given little attention to this subject,

that all this expenditure is widely distributed,

and therefore beneficial to the people ; but

this apology does not bear in mind that it is

not bestowed in any productive industry, or on

any useful object. The magnitude of this waste

will appear by a contrast with other

expenditures. For instance, the aggregate

capital of all the joint-stock companies in

England, of which there was any known record in

1842, embracing canals, docks, bridges,

insurance companies, banks, gas-lights, water,

mines, railways, and other miscellaneous objects, was about $835,000,000; a sum which has

been devoted to the welfare of the people, but how

much less in amount than the War Debt ! For the

six years ending in 1836, the average payment for

interest on this debt was about $140,000,000 annually. If we add to this sum, $60,000,000 during

this same period paid annually to the army r navy,,

and ordnance, we shall have $200,000,000 as the

annual tax of the English people, to pay for former

wars and to prepare for new. During this same

period, there was an annual appropriation of only $20,000,000 for all the civil

purposes of the Government. It thus appears that War absorbed ninety

cents of every dollar that was pressed by heavy

taxation from the English people, who seem

almost to sweat blood ! What fabulous monster,

or chimera dire, ever raged with a maw so ravenous?

The remaining ten cents sufficed to maintain the

splendor of the throne, the administration of

justice, and the diplomatic relations with foreign

powers, in short, all the proper objects of a

Christian Nation.*

* I have relied

here and in subsequent pages upon Mc Culloch's Commercial Dictionary; The Edinburgh Geography,

founded on the works of Malte Brun and Balbi ; and the Calculations of Mr. Jay,

in Peace and War, p. 16, and hi his Address

before the Peace Society, pp. 28, 29.

COST OF PREPARATIONS IN TIME OP PEACE

Thus much for the general cost of War. Let us

now look exclusively at the Preparations for War

in time of peace. It is one of the miseries of War,

that, even in Peace, its evils continue to be felt by

the world, beyond any other by which poor suffering

Humanity is oppressed. If Bellona withdraws from

the field, we only lose sight of her flaming torches ;

the bay of her dogs is heard on the mountains, and

civilized man thinks to find protection from their

sudden fury, only by enclosing himself in the barbarous armor of battle. At this moment, the Christian

nations, worshipping a symbol of common brotherhood, live as in intrenched camps, with armed watch,

to prevent surprise from each other. Recognizing

the custom of War as a proper Arbiter of Justice,

they hold themselves perpetually ready for the

bloody umpirage.

It is difficult,

if not impossible, to arrive at any exact estimate of the cost of these Preparations,

ranging under four different heads, Standing

Army ; Navy ; Fortifications and Arsenals ; and

Militia, or irregular troops.

The number of soldiers now affecting to keep the

peace of European Christendom, as a Standing

Army, without counting the Navy, is upwards of

two millions. Some estimates place it as high as

three millions. The army of Great Britain exceeds

300,000 men ; that of France, 350,000 ; that of Russia, 730,000, and is reckoned by some as high as

1,000,000 ; that of Austria, 275,000 ; that of Prussia,

150,000. Taking the smaller number, and supposing

these two millions to require for their annual support an average sum of only

$150 each, the result would be $300,000,000, for

their sustenance alone ; and reckoning one

officer to ten soldiers, and allowing to each of the latter an English shilling a day,

or $87 a year, for wages, and to the former an average salary of $500 a year, we shall have for the

pay of the whole no less than $256,000,000, or an

appalling sum-total, for both sustenance and pay, of

$556,000,000. If the same calculation be made,

supposing the forces three millions, the sum-total

will be $835,000,000 ! But to this enormous sum

another still more enormous must be added, on account of the loss sustained by the withdrawal of two

millions of hardy, healthy men, in the bloom of life,

from useful, productive labor. It is supposed that

it costs an average sum of $500 to rear a soldier ;

and that the value of his labor, if devoted to useful

objects, would be $150 a year. The Christian

Powers, therefore, in setting apart two millions of

men, as soldiers, sustain a loss of $1,000.000,000 on

account of their training ; and $300,000,000 annually, on account of their labor, in addition to the

millions already mentioned as annually expended

for sustenance and pay. So much for the cost of

the standing army of European Christendom in

time of Peace.

Glance now at the Navy of European Christendom. The Royal Navy of Great Britain consists at

present of 557 ships of all classes ; but deducting

such as are used for convict ships, floating chapels,

coal depots, the efficient navy embraces 88 sail of

the line; 109 frigates; 190 small frigates, corvettes, brigs, and cutters, including packets ; 65

steamers of various sizes ; 3 troop-ships and yachts ;

in all, 455 ships. Of these, there were in commission,

in 1839, 190 ships, carrying in all 4,202 guns. The

number of hands was 34,465. The Navy of France,

though not comparable in size with that of England,

is of vast force. By royal ordinance of 1st January, 1837, it was fixed in time of peace at 40 ships

of the line, 50 frigates, 40 steamers, and 19 smaller

vessels ; and the amount of crews, in 1839, was

20,317 men. The Russian Navy consists of two

large fleets in the Gulf of Finland and the Black

Sea ; but the exact amount of their force and their

available resources has been a subject of dispute

among naval men and publicists. Some idea of the

size of the navy may be derived from the number of

hands. The crews of the Baltic fleet amounted, in

1837, to not less than 30,800 men ; and those of the

fleet in the Black Sea to 19,800, or altogether

50,600, being nearly equal-to those of England and

France combined. The Austrian Navy embraced, in

1837, 8 ships of the line, 8 frigates, 4 sloops,

6 brigs, 7 schooners or galleys, and a quantity of

smaller vessels ; the number of men in its service, in

1839, was 4,547. The Navy of Denmark embraced,

at the close of 1837, 7 ships of the line, 7 frigates,

5 sloops, 6 brigs, 3 schooners, 5 cutters, 58 gun-

boats, 6 gun-rafts, and three bomb-vessels, requiring about 6,500 men. The Navy of Sweden and

Norway consisted recently of 238 gunboats, 11

ships of the line, 8 frigates, 4 corvettes, 6 brigs,

with several smaller vessels. The Navy of Greece

is 32 ships of war, carrying 190 guns and 2,400

men. The Navy of Holland, in 1839, was 8 ships

of the line, 21 frigates, 15 corvettes, 21 brigs, and

95 gunboats. Of the immense cost of all these

mighty Preparations for War, it is impossible to

give an accurate idea. But we may lament that

means, so gigantic, should be applied by European

Christendom to the erection, in time of Peace, of

such superfluous wooden walls !

In the Fortifications and Arsenals of Europe,

crowning every height, commanding every valley,

and frowning over every plain and every sea, wealth

beyond calculation has been sunk. Who can tell

the immense sums expended in hollowing out, for

purposes of War, the living rock of Gibraltar?

Who can calculate the cost of all the Preparations

at Woolwich, its 27,000 cannons, and its hundreds

of thousands of small arms ? France alone contains

upwards of one hundred and twenty fortified places.

And it is supposed that the yet unfinished fortifications of Paris have cost upward of fifty millions of

dollars!

The cost of the Militia, or irregular troops, the

Yeomanry of England, the National Guards of

Paris, and the Landwehr and Landsturm of Prussia,

must add other incalculable sums to these enormous

amounts.

Turn now to the United States, separated by a

broad ocean from immediate contact with the Great

Powers of Christendom, bound by treaties of amity

and commerce with all the nations of the earth,

connected with all by the strong ties of mutual

interest, and professing a devotion to the principles of Peace. Are the Treaties of Amity mere

words ? Are the Relations of Commerce and mutual

interest mere things of a day ? Are the professions

of Peace vain ? Else why not repose in quiet,

unvexed by Preparations for War?

Enormous as are

these expenses in Europe, those in our own

country are still greater in proportion to other

expenditures of the Federal Government.

It appears that

the average annual expenditures of the Federal

Government, for the six 3 T ears ending with

1840, exclusive of payments on account of debt,

were $26,474,892. Of this sum, the average

appropriation each year for military and naval

purposes, amounted to $21,328,903, being eighty

per cent of the whole amount ! Yes ; of all the

annual appropriations by the Federal Government,

eighty cents in every dollar were applied in

this irrational and unproductive manner. The

remaining twenty cents sufficed to maintain the

Government in all its branches, Executive, Legislative,

and Judicial ; the administration of justice ; our relations with foreign nations ; the post-office, and all the

lighthouses, which, in happy useful contrast with

any forts, shed their cheerful signals over the rough

waves, beating upon our long and indented coast,

from the Bay of Fundy to the mouth of the Mississippi. A table of the relative

expenditures of nations, for Military

Preparations in time of Peace, exclusive of

payments on account of debts, exhibits results which will surprise the advocates of

economy in our country. These are in proportion

to the whole expenditure of Government ;

In Austria, as 33 per cent ;

In France, as 38 per cent ;

In Prussia, as 44 per cent ;

In Great Britain, as 74 per cent ;

In the UNITED STATES, as 80 per cent ! *

* I have verified

these results by the expenditures of these different

nations ; but I do little more than follow Mr.

Jay, who has illustrated this important point

with his accustomed accuracy. Address, p. 30.

To this stupendous waste may be added the still

larger and equally superfluous expenses of the

Militia throughout the country, placed recently by

a candid and able writer at $50,000,000 a year ! *

* Jay's Peace and

War, p. 13.

By a table * of the expenditures of the United

States, exclusive of payments on account of the

Public Debt, it appears, that, in fifty-three years

from the formation of our present Government, from

1789 down to 1843, $246,620,055 have been expended for civil purposes, comprehending the executive, the legislative, the

judiciary, the post-office, lighthouses, and

intercourse with foreign governments.

* American Almanac for 1845, p. 143.

During this same period, $368,626,594

have been devoted to the Military establishment,

and $170,437,684 to the Naval establishment; the

two forming an aggregate of $538,964,278. Deducting from this sum appropriations during three

years of war, and we shall find that more than

four hundred millions were absorbed by vain Preparations in time of Peace for

War. Add to this amount, a moderate sum for the

expenses of the Militia during the same period,

which, as we have already seen, have been placed

at $50,000.000 a year, for the past years, we

may take an average of $25,000,000, and we shall

have the enormous sum of $1,335,000,000 to be

added to the $400,000,000 ; the whole, amounting

to seventeen hundred and thirty-five millions of

dollars, a sum not easily conceived by the human

faculties, sunk under the sanction of the

Government of the United States in mere peaceful

Preparations for War; more than seven times as

much as was dedicated by the Government, during the same period, to all other

purposes whatsoever !

COST OF WAR AND EDUCATION

COMPARED

From this serried

array of figures, the mind instinctively retreats. If we examine them from a

nearer point of view, and, selecting some particular

part, compare it with the figures representing other

interests in the community, they will present a front

still more dread. Let us attempt the comparison.

Within a short

distance of this city stands an

institution of learning, which was one of the earliest cares of the early forefathers of the country, the

conscientious Puritans. Favored child of an age

of trial and struggle ; carefully nursed through a

period of hardship and anxiety ; endowed at that

time by the oblations of men like Harvard ; sustained from its first foundation by the paternal

arm of the Commonwealth, by a constant succession of munificent bequests, and by

the prayers of good men, the University at

Cambridge now invites our homage as the most

ancient, most interesting, and most important seat of learning in

the land ; possessing the oldest and most valuable

library ; one Of the largest museums of mineralogy

and natural history ; a School of Law, which

annually receives into its bosom more than one

hundred and fifty sons from all parts of the Union,

where they listen to instruction from professors

whose names have become among the most valuable

possessions of the land ; a School of Divinity, the

nurse of true learning and piety ; one of the largest

and most flourishing Schools of Medicine in the

country ; besides these, a general body of teachers,

twenty-seven in number, many of whose names help

to keep the name of the country respectable in

every part of the globe, where science, learning,

and taste are cherished ; the whole, presided over

at this moment, by a gentleman early distinguished

in public life by unconquerable energies and masculine eloquence, at a later period, by the unsurpassed ability with which he administered the affairs

of our city, and now, in a green old age, full of

years and honors, preparing to lay down his present

high trust.*

* Hon. Josiah

Quincy.

Such is Harvard University ; and as

one of the humblest of her children, happy in the

recollection of a youth nurtured in her classic retreats, I cannot allude to her without an expression

of filial affection and respect.

It appears from the last Report of the Treasurer,

that the whole available property of the University,

the various accumulation of more than two centuries of generosity, amounts to $703,175.

Change the scene,

and cast your eyes upon another object. There

now swings idly at her moorings, in this harbor, a ship of the line, the Ohio,

carrying ninety guns, finished as late as 1836, for

$547,888 ; repaired only two years afterwards, in

1838, for $223,012 ; with an armament which has

cost $53,945 ; making an amount of $834,845, * as

the actual cost at this moment of that single ship ;

more than $100,000 beyond all the available

wealth of the richest and most ancient seat of

learning in the land !

* Document

No 132, House of Representatives, Third Session,

Twenty-Seventh Congress.

Choose ye, my fellow-citizens

of a Christian state, between the two caskets

that wherein is the loveliness of knowledge and

truth, or that which contains the carrion death.

I refer thus particularly to the Ohio, because she

happens to be in our waters. But in so doing, I do

not take the strongest case afforded by our Navy.

Other ships have absorbed still larger sums. The

expense of the Delaware, in 1842, had been

$1,051,000.

Pursue the comparison still farther. The expenditures of the University during the last year, for the

general purposes of the College, the instruction of

the Undergraduates, and for the Schools of Law and

Divinity, amount to $46,949. The cost of the Ohio

for one year of service, in salaries, wages, and provisions, is $220,000; being $175,000 above the

annual expenditures of the University, and more

than four times as much as those expenditures. In

other words, for the annual sum lavished on a

single ship of the line, four institutions like Harvard University might be sustained throughout the

country !

Still further pursue the comparison. The pay of

the Captain of a ship like the Ohio is $4,500, when

in service ; $3,500, when on leave of absence, or off

duty. The salary of the President of Harvard

University is $2,205 ; without leave of absence, and

never, off duty !

If the large endowments of Harvard University

are dwarfed by a comparison with the expense of a

single ship of the line, how much more so must it

be with those of other institutions of learning and

beneficence, less favored by the bounty of many

generations. The average cost of a sloop of war is

$315,000 ; more, probably, than all the endowments

of those twin stars of learning in the Western part

of Massachusetts, the Colleges at Williamstown

and Amherst, and of that single star in the East,

the guide to many ingenuous youth, the Seminary

at Andover. The yearly cost of a sloop of war in

service is about $50,000, more than the annual

expenditures of these three institutions combined.

I might press the comparison with other

institutions of Beneficence, with the annual expenditures

for the Blind that noble and successful charity,

which has shed true lustre upon our Commonwealth

amounting to $12,000 ; and the annual expenditures for the Insane of the Commonwealth, another

charity dear to humanity, amounting to $27,844.

Take all the institutions of Learning and Beneficence, the crown jewels of the Commonwealth,

the schools, colleges, hospitals, asylums, and the

sums by which they have been purchased and preserved are trivial and beggarly, compared with the treasures squandered, within the borders of Massachusetts, in vain Preparations for War. There is the

Navy Yard at Charlestown, with its stores on hand,

costing $4,741,000 ; the fortifications in the harbors

of Massachusetts, where incalculable sums have

been already sunk, and in which it is now proposed

to sink $3,853,000 more ; * and besides, the Arsenal

at Springfield, containing, in 1842, 175,118 muskets,

valued at $2,999,998, ** and fed by an annual appropriation of $200,000 ; but whose highest value will

ever be, in the judgment of all lovers of truth, that

it inspired a poem, which in its influence will be

mightier than a battle, and will endure when arsenals and fortifications have crumbled to earth.

* Document; Report

of Secretary of War; No. 2 Senate,

Twenty-Seventh Congress, Second Session ; where

it is proposed to invest in a general system of

land defenses, $51,677,929.

** Exec. Documents of 1842-43, vol. i., No. 3.

Some of the verses of this Psalm of Peace may

happily relieve the detail of statistics, while they

blend with my argument.

Were half the power that fills the world with terror,

Were half the wealth bestowed on camp and courts,

Given to redeem the human mind from error,

There were no need of arsenals and forts.

The warrior's name would be a name abhorred !

And every nation that should lift again

Its hand against its brother, on its forehead

Would wear for evermore the curse of Cain !

Look now for one moment at a high and peculiar

interest of the nation, the administration of justice.

Perhaps no part of our system is regarded, by the

enlightened sense of the country, with more pride

and confidence. To this, indeed, all other concerns

of Government, all its complications of machinery,

are in a manner subordinate, since it is for the sake

of justice that men come together in states and

establish laws. What part of the Government can

compare, in importance, with the Federal Judiciary,

that great balance-wheel of the Constitution, controlling the relations of the States to each other, the

legislation of Congress and of the States, besides

private interests to an incalculable amount? Nor

can the citizen, who discerns the True Glory of his

country, fail to recognize in the judicial labors of

MARSHALL, now departed, and in the immortal

judgments of STORY, who is still spared to us serus in coelum redeat a higher claim to admiration

and gratitude than can be found in any triumph of

battle. The expenses of the administration of

justice throughout the United States, under the

Federal Government, in 1842, embracing the salaries of judges, the cost of juries, court-houses, and

all its officers ; in short, all the outlay by which

justice, according to the requirement of Magna

Charta, is carried to every' man's door, amounted to

$560,990, a larger sum than is usually appropriated for this purpose, but how insignificant, compared

with the cormorant demands of Army and Navy !

Let me allude to one more curiosity of waste. It

appears, by a calculation founded on the expenses

of the Navy, that the average cost of each gun

carried over the ocean, for one year, amounts to

about fifteen thousand dollars, a sum sufficient to

sustain ten or even twenty professors of Colleges,

and equal to the salaries of all the Judges of the

Supreme Court of Massachusetts and the Governor

combined !

THE GLACIER OF WAR

Such are

illustrations of that tax which the nations,

constituting the great Federation of

civilization, and particularly our own country,

impose on the people, in time of profound Peace,

for no permanent productive work, for no institution of learning, for no

gentle charity, for no purpose of good. As we

wearily climb, in this survey, from expenditure

to expenditure, from waste to waste, we seem to

pass beyond the region of ordinary calculation ;

Alps on Alps arise, on whose crowning heights of

everlasting ice, far above the habitations of man,

where no green thing lives, where no creature draws

its breath, we behold the cold, sharp, flashing

glacier of War.

DISARMING OP THE NATIONS

In the contemplation of this spectacle, the soul

swells with alternate despair and hope ; with despair, at the thought of such wealth, capable of

rendering such service to Humanity, not merely

wasted, but given to perpetuate Hate ; with hope, as

the blessed vision arises of the devotion of all these

incalculable means to the purposes of Peace. The

whole world labors at this moment with poverty and

distress ; and the painful question occurs to every

observer, in Europe more than here at home, What

shall become of the poor the increasing Standing

Army of the poor ? Could the humble voice that

now addresses you penetrate those distant counsels,

or counsels nearer home, it would say, disband your

Standing Armies of soldiers, apply your Navies

to purposes of peaceful and enriching commerce,

abandon Fortifications and Arsenals, or dedicate

them to works of Beneficence, as the statue of

Jupiter Capitolinus was changed to the image of a

Christian saint ; in fine, utterly forsake the present

incongruous system of Armed Peace.

That I may not seem to reach this conclusion

with too much haste, at least as regards our own

country, I shall consider briefly, as becomes the

occasion, the asserted usefulness of the national

armaments ; and shall next expose the outrageous

fallacy, at least in the present age, and among the

Christian Nations, of the maxim by which they are

vindicated, that, in time of Peace, we must prepare

for War.

What is the use of the Standing Army of the

United States? It has been a principle of freedom,

during many generations, to avoid a standing army ;

and one of the complaints, in the Declaration of

Independence, was that George III. had quartered

large bodies of troops in the colonies. For the first

years, after the adoption of the Federal Constitution, during our weakness, before our power was

assured, before our name had become respected in

the family of nations, under the administration of

Washington, a small sum was deemed ample for the

military establishment of the United States. It was

only when the country, at a later day, had been

touched by martial insanity, that, in imitation of

monarchical states, it abandoned the true economy

of a Republic, and lavished means, begrudged to

purposes of Peace, in vain preparation for War. It

may now be said of our army, as Dunning said of

the influence of the crown, it has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished. At this

moment, there are, in the country, more than fifty-

five military posts. It would be difficult to assign a

reasonable apology for any of these unless, perhaps, on some distant Indian frontier. Of what use

is the detachment of the second regiment of Artillery at the quiet town of New London, in Connecticut? Of what use is the detachment of the first

regiment of Artillery in that pleasant resort of

fashion, Newport? By exhilarating music and

showy parade, they may amuse an idle hour ; but it

is doubtful if emotions of a different character will

not be aroused in thoughtful bosoms. He must

have lost something of his sensibility to the dignity

of human nature, who can observe, without at least a

passing regret, all the details of discipline, drill,

marching, countermarching, putting guns to the

shoulder, and then dropping them to the earth,

which fill the life of the poor soldier, and prepare

him to become 'the rule inanimate part of that

machine, to which an army has been likened by the

great living master of the Art of War. And this

sensibility may be more disturbed, by the spectacle

of a chosen body of ingenuous youth, under the

auspices of the Government, amidst the bewitching scenery of West Point, painfully trained to these

same exercises at a cost to the country, since

the establishment of this Academy, of upwards of

four millions of dollars.

In Europe, Standing Armies are supposed to be

needed to sustain the power of governments ; but

this excuse cannot prevail here. The monarchs of

the Old World, like the chiefs of the ancient German tribes, are upborne by the

shields of the soldiery. Happily with us, government springs from

the hearts of the people, and needs no janizaries

for its support.

But I hear the voice of some defender of this

abuse, some upholder of this " rotten borough,"

crying, the Army is needed for the defence of

the country ! As well might you say, that the

shadow is needed for the defence of the body ; for what is the army of the

United States but the feeble shadow of the

American people? In placing the army on its

present footing, so small in numbers compared

with the forces of great European States, our

Government has tacitly admitted its superfluousness for defence.

It only remains to declare distinctly, that the

country will repose, in the consciousness of right, without the extravagance of

supporting soldiers, unproductive consumers of the

fruits of the earth, who might do the State good

service in the various departments of useful industry.

What is the use of the Navy of the United States?

The annual expense of our Navy, during recent

years, has been upwards of six millions of dollars.

For what purpose is this paid ? Not for the apprehension of pirates, since frigates and ships of the

line are of too great bulk for this service. Not

for the suppression of the Slave Trade ; for, under

the stipulations with Great Britain, we employ' only

eighty guns in this holy alliance. Not to protect

our coasts ; for all agree that our few ships would

form an unavailing defence against any serious attack. Not for these purposes,

you will admit ; but for the protection of our

Navigation. This is not the occasion for minute

calculation. Suffice it to say, that an

intelligent merchant, extensively engaged in commerce for the last twenty years, and

who speaks, therefore, with the authority of knowledge, has demonstrated, in a tract of perfect clearness, that the annual profits of the whole

mercantile

marine of the country do not equal the annual

expenditure of our Navy. Admitting the profit of

a merchant ship to be four thousand dollars a year,

which is a large allowance, it will take the earnings

of one hundred ships to build and employ for one

year a single sloop of war one hundred and fifty

ships to build and employ a frigate, and nearly three

hundred ships to build and employ a ship of the

line. Thus, more than five hundred ships must do a

profitable business, to earn a sufficient sum for the

support of this little fleet. Still further, taking a

received estimate of the value of the mercantile

marine of the United States at forty millions of

dollars, we find that it is only a little more than six

times the annual cost of the navy ; so that this

interest is protected at a charge of more than fifteen

per cent of its whole value ! Protection at such

a price is not less ruinous than one of Pyrrhus's

victories !

But it is to the Navy, as an unnecessary arm of

national defence, and as part of the War establishment, that I confine my

objection. So far as it is required for purposes

of science and for the police of the seas, to

scour them of pirates, and, above all, to defeat

the hateful traffic in human flesh, it is an

expedient instrument of Government, and cannot be obnoxious as a portion of the

machinery of War. But surety, a navy, supported

at immense cost in time of Peace, to protect navigation against the piracies of civilized nations, is

absurdly superfluous. The free cities of Hamburg

and Bremen, survivors of the great Hanseatic

League, with a commerce that whitens the most

distant seas, are without a single ship of war.

Following this prudent example, the United States

may be willing to abandon an institution which

has already become a vain and most expensive

toy !

What is the use of the Fortifications of the United

States? We have already seen the enormous sums,

locked in the dead hands the odious mortmain

of their everlasting masonry. Like the pyramids,

they seem by mass and solidity to defy time. Nor

can I doubt, that hereafter, like these same monuments, they will be looked upon

with wonder, as the types of an extinct

superstition, not less degrading than that of

Ancient Egypt the superstition of War. It is in

the pretence of saving the country from the

horrors of conquest and bloodshed that they

are reared. But whence the danger? On what side?

What people is there any just cause to fear? No

Christian nation threatens our borders with

piracy or rapine. None will. Nor in the existing

state of civilization, and under existing International Law, is it possible to suppose

any War, with such a nation, unless we voluntarily

renounce the peaceful Tribunal of Arbitration, and

take an appeal to Trial by Battle. The fortifications might be of service in waging this impious

appeal. But it must be borne in mind that they

would invite the attack, which they might be inadequate to defeat. It is a rule now recognized, even

in' the barbarous code of War, one branch of which

has been illustrated with admirable ability in the

diplomatic correspondence of Mr. Webster, that

non-combatants on land shall not in any way be

molested, and that the property of private persons

on land shall in all cases be held sacred. So firmly

did the Duke of Wellington act upon this rule, that,

throughout the revengeful campaigns of Spain, and

afterwards when he entered France, flushed with

the victory of Waterloo, he directed his army to

pay for all provisions, and even for the forage of

their horses. War is carried on against public

property against fortifications, navy yards, and arsenals. But if these do not

exist, where is the aliment, where is the fuel

for the flame ? Paradoxical as it may seem, and disparaging to the

whole trade of War, it may be proper to inquire,

whether, according to the acknowledged Laws,

which now govern this bloody Arbitrament, every

new fortification and every additional gun in our

harbor is not less a safeguard than a source of danger to the city ? Plainly

they draw the lightning of battle upon our

homes, without, alas, any conductor to hurry its terrors innocently beneath the

concealing bosom of the earth !

What is the use of the Militia of the United States

?

This immense system spreads, with innumerable

suckers, over the whole country, draining its best

life-blood, the unbought energies of the youth. The

same painful discipline, which we have observed in the soldier, absorbs their

time, though, of course, to a less degree than

in the regular army. Theirs also is the savage

pomp of War. We read with astonishment of the

painted flesh and uncouth vestments of our

progenitors, the ancient Britons. But the

generation must soon come, that will regard,

with equal wonder, the pictures of their ancestors closely dressed in padded and well-buttoned

coats of blue, " besmeared with gold," surmounted

by a huge mountain-cap of shaggy bear-skin, and

with a barbarous device, typical of brute force, a

tiger, painted on oil-skin, tied with leather to their

backs ! In the streets of Pisa, the galley-slaves

are compelled to wear dresses stamped with the

name of the crime for which they are suffering

punishment, as theft, robbery, murder. It is not

a little strange, that Christians, living in a land

' where bells have tolled to church," should voluntarily adopt devices,

which, if they have any meaning, recognize the example of beasts as worthy of

imitation by man.

The general

considerations, which belong to the subject of

Preparations for War, will illustrate the

inanity of the Militia for purposes of national

defence. I do not know, indeed, that it is now

strongly advocated on this ground. It is oftener

approved as an important part of the police of

the country. I would not undervalue the

blessings of an active, efficient, ever-wakeful

police ; and I believe that such a police has

been long required in our country. But the

Militia, composed of youth of undoubted

character, though of untried courage and little

experience, is inadequate for this purpose. No person, who has seen this arm of the police in an

actual riot, can hesitate in this judgment. A very

small portion of the means, absorbed by the Militia,

would provide a substantial police, competent to all

the emergencies of domestic disorder and violence.

The city of Boston has long been convinced of the

inexpediency of a Fire Department composed of

accidental volunteers. A similar conviction with

regard to the police, it is hoped, may soon pervade

the country.

I am well aware, that efforts to abolish the

Militia are encountered by some of the dearest

prejudices of the common mind ; not only by the

War Spirit; but by that other spirit, which first

animates childhood, and, at a later day, u children

of a larger growth," inviting to finery of dress and

parade, the same spirit which fantastically bedecks the dusky feather-cinctured chief of the soft

regions warmed by the tropical sun ; which inserts

rings in the noses of the North-American Indian ;

which slits the ears of the Australian savage ; and tattoos the New-Zealand cannibal.

Such is a review of the true character and value

of the national armaments of the United States !

It will be observed that I have thus far regarded

them in the plainest light of ordinary worldly economy, without reference to

those higher considerations, founded on the nature and history of

man, and the truths of Christianity, which pronounce them to be vain. It is grateful to know,

that, though they may yet have the support of what

Jeremy Taylor calls the " popular noises," still the

more economical, more humane, more wise, more

Christian system is daily commending itself to wide

circles of good people. On its side are all the virtues

that truly elevate a state. Economy, sick of pigmy

efforts to staunch the smallest fountains and rills

of exuberant expenditure, pleads that here is an

endless, boundless, fathomless river, an Amazon of

waste, rolling its prodigal waters turbidly, ruinously,

hatefully, to the sea. It chides us with unnatural

inconsistency when we strain at a little twine and

paper, and swallow the monstrous cables and armaments of War. Wisdom frowns on these Preparations

as calculated to nurse sentiments inconsistent

with Peace. Humanity pleads for the surpassing

interests of Knowledge and Benevolence, from

which such mighty means are withdrawn. Christianity calmly rebukes the spirit in which they have

their origin, as of little faith, and treacherous to

her high behests ; while History, exhibiting the

sure, though gradual, Progress of Man, points

with unerring finger to that destiny of True

Grandeur, when Nations, like individuals

disowning War as a proper Arbiter of Justice

shall abandon the oppressive apparatus of

Armies, Navies, and Fortifications by which it is impiously waged.

BARBAROUS MOTTOES AND EMBLEMS

And now, before

considering the sentiment, that, in time of

Peace, we must prepare for War, I hope I shall

not seem to descend from the proper sphere of

this discussion, if I refer to the parade of barbarous mottoes, and of emblems from beasts, as

furnishing another impediment to the proper appreciation *bf these Preparations.

These mottoes and emblems, prompting to War, are

obtruded on the very ensigns of power and honor

; and men, careless of their discreditable

import, learn to regard them with patriotic

pride. Beasts, and birds of prey, in the

armorial bearings of nations and individuals,

are selected as exemplars of Grandeur. The lion

is rampant on the flag of England ; the leopard

on the flag of Scotland ; a double-headed eagle

spreads its wings on the imperial standard of

Austria, and again on that of Russia. After exhausting

the known kingdom of nature, the pennons of

knights, like the knapsacks of our Militia, were

disfigured by imaginary and impossible monsters,

griffins, hippogriffs, unicorns, all intended to

represent the excess of brute force. The

people of Massachusetts have unconsciously

adopted this early standard. In the escutcheon

which is used as the seal of the state, there is

an unfortunate combination of suggestions, to which I refer briefly,

by way of example. On that part, which, in the

language of heraldry, is termed the shield, is an

Indian, with a bow in his hand certainly, no

agreeable memento, except to those who find honor

in the disgraceful wars where our fathers robbed

and murdered King Philip, of Pokanoket, and his

tribe, rightful possessors of the soil. The crest is

a raised arm, holding, in a threatening attitude, a

drawn sabre being precisely the emblem once borne on the flag of Algiers. The

scroll, or legend, consists of the last of those

two favorite verses, in questionable Latin, from

an unknown source, which we first encounter, as

they were inscribed by Algernon Sydney, in the

Album at the University of Copenhagen, in Denmark :

Manus haec, inimica tyrannis,

Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem.

The Legislature of Massachusetts, with singular

unanimity, has adopted resolutions expressing an

earnest desire for the establishment of a High

Court of Nations to adjudge international controversies, and thus supersede the Arbitrament of

War. It would be an act of moral dignity, consistent with these professions of Peace, and becoming

the character which it vaunts before the world, to

abandon its bellicose escutcheon at least, to

erase that Algerine emblem, fit only for corsairs,

and those words of questionable Latin, which tend

to awaken the idea of ignorance and brute force.

If a Latin motto be needed, it might be those words

of Virgil, " Pacisque irnpouere morem ; " or that

sentence of noble truth from Cicero, " Sine SUMMA JUSTITIA rempublican geri nullo modo posse."

Where the spirit of these words prevailed, there

would be little occasion to consider the question

of Preparations for War.

THE MAXIM, "IN TIME OF PEACE, PREPARE FOR

WAR," EXAMINED

The maxim, that, in time of peace, we must prepare for War, has been transmitted from distant

ages when brute force prevailed. It is the terrible

inheritance, damnosa haereditas, which painfully

reminds present generations of their relations

with the Past. It belongs to rejected dogmas of

barbarism. It is the companion of those harsh

rules of tyranny, by which the happiness of the

many has been offered up to the propensities of the

few. It is the child of suspicion and the forerunner

of violence. Having in its favor the almost uninterrupted usage of the world, it possesses a hold

on popular opinion, which is not easily unloosed.

And yet, no conscientious man can fail, on careful

observation, to detect its mischievous fallacy at

least, among Christian Nations in the present age

a fallacy, the most costly the world has witnessed ;

which dooms nations to annual tribute, in comparison with which all extorted by conquest are as the

widow's mite by the side of Pharisaical contributions. So, true is what Rousseau said, and

Guizot has since repeated, " that a bad principle is

far worse than a bad fact;" for the operations of

the one are finite, while those of the other are

infinite.

I speak of this principle with earnestness ; for

I

believe it to be erroneous and false, founded in

ignorance and barbarism, unworthy of an age of

light, and disgraceful to Christians. I have called

it a principle ; but it is a mere prejudice sustained

by vulgar example only, and not by enlightened

truth in obeying which, we imitate the early

mariners, who steered from headland to headland

and hugged the shore, unwilling to venture upon

the broad ocean, where their guide was the luminaries of Heaven.

Dismissing the actual usage of nations, on the

one side, and the considerations of economy on the

other, let us regard these Preparations for War, in

the simple light of reason, in a just appreciation of

the nature of man, and in the injunctions of the

highest truth. Our conclusion will be very easy.

They are pernicious on two grounds ; and whoso

would vindicate them must satisfactorily answer

these two objections, first, because they inflame the

people, exciting to deeds of violence, otherwise

alien to their minds ; and secondly, because, having

their origin in the low motive of distrust and hate,

they inevitably, by a sure law of the human mind,

excite a corresponding feeling in other nations.

Thus, in fact, are they the promoters of War, rather

than the preservers of Peace.

In illustration of the first objections, it will occur at once to every inquirer, that the possession of

power is always in itself dangerous, that it tempts

the purest and highest natures to self-indulgence,

that it can rarely be enjoyed without abuse ; nor is

the power to employ force in War an exception to this law. History teaches that nations, possessing

the greatest armaments, have always been the most

belligerent ; while feebler powers have enjoyed, for

a longer period, the blessings of Peace. The din of

War resounds throughout more than seven hundred

years of Roman history, with only two short lulls of

repose ; while smaller states, less potent in arms,

and without the excitement to quarrel on this account, have enjoyed long eras of Peace. It is not

in the history of nations only that we find proofs of

this law. Like every moral principle, it applies

equality to individuals. The experience of private

life, in all ages, confirms it. The wearing of arms

has always been a provocative to combat. It has

excited the spirit and furnished the implements of

strife. Reverting to the progress of society in

modern Europe, we find that the odious system of

private quarrels, of hostile meetings even in the

street, continued so long as men persevered in the

habit of wearing arms. Innumerable families were

thinned by death received in these hasty, unpremeditated encounters ; and the lives of scholars and

poets were often exposed to their rude chances.

Marlowe, " with all his rare learning and wit,"

perished ignominiously under the weapon of an

unknown adversary ; and Savage, whose genius and

misfortune inspired the friendship and eulogy of

Johnson, was tried for murder committed in a sudden broil. " The expert swordsman," says Mr.

Jay,* " the practised marksman, is ever more ready

to engage in personal combats, than the man who is

unaccustomed to the use of deadly weapons,.

* Address before

the American Peace Society, pp. 23, 24

In

those portions of our country where it is supposed

essential to personal safety to go armed with pistols

and bowie-knives, mortal affrays are so frequent as

to excite but little attention, and to secure, with

rare exceptions, impunity to the murderer ; whereas

at the North and East, where we are unprovided

with such facilities for taking life, comparatively

few murders of the kind are perpetrated. We

might, indeed, safely submit the decision of the

principle we are discussing to the calculations of

pecuniary interest. Let two men, equal in age and

health, apply for an insurance on their lives : one

known to be ever armed to defend his honor and his

life against every assailant ; and the other, a meek,

unresisting Quaker ; can we doubt for a moment

which of these men would be deemed by the

Insurance Company most likely to reach a good

old age?"

The second objection is founded on that law of the

human mind, in obedience to which, the sentiment of

distrust or hate, of which these Preparations are

the representatives, must excite a corresponding

sentiment in others. This law is a part of the

unalterable nature of man, recognized in early ages,

though too rarely made the guide to peaceful intercourse among nations. It is an expansion of the

old Horatian adage, Si vis me fare, dolendum est

primum ipsi tibi; if you wish me to weep, you must

yourself first weep. Nobody can question its force

or its applicability ; nor is it too much to say, that

it distinctly declares, that Military Preparations by

one nation, in time of professed Peace, must naturally prompt similar Preparations by other nations,

and quicken ever}' where, within the circle of their

influence, the Spirit of War. So are we all knit

together, that the feelings in our own bosoms

awaken corresponding feelings in the bosoms of

others ; as harp answers to harp in its softest vibration ; as deep responds to

deep in the might of its power. What within us

is good invites the good in our brother ;

generosity begets generosity ; love wins love ;

Peace secures Peace ; while all within us that

is bad challenges the bad in our brother ;

distrust engenders distrust ; hate provokes hate

; War arouses War.

This beautiful law

may be seen in numerous illustrations. Even the miserable maniac, in whose

mind the common rules of conduct are overthrown,

confesses its overruling power ; and the vacant stare

of madness may be illumined by a word of love.

The wild beasts confess it : and what is the story of

Orpheus, whose music drew, in listening rapture, the

lions and panthers of the forest ; or of St. Jerome,

whose kindness soothed a lion to lie down at his

feet, but expressions of its prevailing influence ? *

* Scholars will remember the incident recorded by Homer in

the Odyssey (XIV. 30, 31), where Ulysses, on reaching his loved

Ithaca, is beset by dogs, who are described as wild beasts in

ferocity, and who, barking, rushed towards him ; but he, with

craft (that is the word of Homer) seats himself upon the earth, and lets his

staff fall from his hands. A similar incident is

noticed by Mr. Mure, in his entertaining travels in Greece; and also

by Mr. Borrow, in his Bible in Spain. Pliny remarks that all

dogs may be appeased in the same way. Impetus eorum, et

sasvitia mitigantur ab nomine considente humi. Nat. His. Lib.

VIII. cap. 40.

It speaks also in the examples of literature. Here,

at the risk of protracting this discussion, I am

tempted to glance at some of these curious instances,

asking your indulgence, and trusting that I may

not seem to attach undue meaning to them, and

especially disclaiming any conclusions beyond the

simple law which they illustrate.

Looking back to the historic dawn, one of the

most touching scenes which we behold, illumined by

that Auroral light, is the peaceful visit of the aged

Priam to the tent of Achilles, entreating the body of

his son. The fierce combat has ended in the death

of Hector, whose unhonored corse the bloody Greek

has already trailed behind his chariot. The venerable father, after twelve days

of grief, is moved to regain the remains of the

Hector he had so dearly loved. He leaves his

lofty cedarn chamber, and with a single aged

attendant, unarmed, repairs to the Grecian camp,

by the side of the distant-sounding sea. Entering alone, he finds Achilles in his

tent, with two of his chiefs. Grasping his knees,

the father kisses those terrible homicidal hands

which had taken the life of his son. The heart of

the inflexible, the angry, the inflamed Achilles,

touched by the sight which he beholds, responds to

the feelings of Priam. He takes the suppliant by the hand, seats him by his

side, consoles his grief, refreshes his weary

body, and concedes to the prayers of a weak, unarmed old man, what all Troy in

arms could not win. In this scene, which fills a

large space in the Iliad, the master poet, with unconscious power, has presented a picture of the

omnipotence of that law, making all mankind of kin,

in obedience to which no word of kindness, no act

of confidence, falls idly to the earth.

Among the legendary passages of Roman history,

perhaps none makes a deeper impression, than that

scene, after the Roman youth had been consumed at Allia, and the invading Gauls under Brennus had

entered the city, where we behold the venerable

Senators of the Republic, too old to flee, and careless of surviving the Roman name, seated each on

his curule chair, in a temple, unarmed, looking, as

Livy says, more august than mortal, and with the

majesty of the gods. The Gauls gaze upon them,

as upon sacred images ; and the hand of slaughter,

which had raged through the streets of Rome, is

stayed by the sight of an assembly of unarmed men.

At length, a Gaul approaches, and with his hand

gently' strokes the silver beard of a Senator,

who, indignant at the license, smites the

barbarian with his ivory staff; which was the

signal for general vengeance. Think you, that a

band of savages could have slain these Senators,

if the appeal to Force had not first been made

by one of their own number? This story, though

recounted by Livy, and also by Plutarch, is

properly repudiated by Niebuhr as a legend ; but

it is none the less interesting, as showing the law by which hostile feelings

are necessarily aroused or subdued.

Other instances present themselves. An admired

picture by Virgil, in his melodious epic, represents a

person, venerable for piety and deserts, assuaging

by words alone a furious populace, which had just

broken into sedition and outrage. Guizot, in his

History of French Civilization,* has preserved a

similar example of what was accomplished by an

unarmed man, in an illiterate epoch, who, employing

the word instead of the sword, subdued an angry

multitude.

* Tom, II. p. 36.

And surely no reader of that noble

historical romance, the Promessi Sposi, can forget

that finest scene, where Fra Christofero, in an age

of violence, after slaying a comrade in a broil, repairs in unarmed penitence to the very presence of

the family and retainers of his victim, and by dignified gentleness, awakens the admiration of those

already mad with rage against him. Another example, made familiar by recent translations of Frithiof's Saga, the Swedish epic, is more emphatic.

The scene is a battle. Frithiof is in deadly combat

with Atle, when the falchion of the latter breaks.

Throwing away his own weapon, he says :

Swordless foeman's life

Ne'er dyed this gallant blade.

The two champions now close in mutual clutch;

they hug like bears, says the Poet:

"Tis o'er ; for Frithiof s matchless strength

Has felled his ponderous size ;

And 'neath that knee, at giant length,

Supine the Viking lies.

"But fails my sword, thou Berserk swart! "

The voice rang far and wide,

" Its point should pierce thy inmost heart,

Its hilt should drink the tide."

" Be free to lift the weaponed hand,"

Undaunted Atle spoke ;

" Hence, fearless, quest thy distant brand !

Thus I abide the stroke."

Frithiof regains his sword, intent to close the

dread debate, while his adversary awaits the

stroke ; but his heart responds to the generous

courage of his foe ; he cannot injure one who

has shown such confidence in him ;

This quelled his ire, this checked his arm,

Outstretched the hand of peace.

I cannot leave

these illustrations, without alluding

particularly to the treatment of the insane,

which teaches, by conclusive example, how strong

in nature must be the principle, that makes us

responsive to the conduct and feelings of others.

When Pinel first proposed to remove the heavy

chains from the raving maniacs of the Paris hospitals, he was regarded as one who saw visions, or

dreamed dreams. At last, his wishes were gratified. The change in the unhappy patients was immediate ; the wrinkled front of evil passions was

smoothed into the serene countenance of Peace.

The old treatment by Force is now universally

abandoned ; the law of Love has taken its place ;

and all these unfortunates mingle together, unvexed

by those restraints, which implied suspicion, and,

therefore, aroused opposition. The warring propensities, which, while hospitals for the insane were

controlled by Force, filled them with confusion and

strife, are a dark but feeble type of the present relations of nations, on whose hands are the heavy

chains of Military Preparations, assimilating the

world to one Great Mad-house ; while the Peace and

good-will, which now abound in these retreats, are

the happy emblems of what awaits mankind when they recognize the supremacy of the higher sentiments, of gentleness, confidence, love ;

making their future might

Magnetic o'er the fixed untrembling heart.

I might dwell also on the recent experience, so

full of delightful wisdom, in the treatment of the

distant, degraded convicts of New South Wales,

showing how confidence and kindness, on the part

of their overseers, awaken a corresponding sentiment even in these outcasts, from whose souls

virtue, at first view, seems to be wholly blotted out.

Thus, from all quarters and sources, the far-off

Past, the far-away Pacific, the verse of the poet, the

legend of history, the cell of the mad-house, the

assembly of transported criminals, the experience

of daily life, the universal heart of man, ascends

the spontaneous tribute to that law, according to

which, we respond to the feelings by which we are

addressed, whether of love or hate, of confidence or

distrust.

It may be urged that these instances are exceptions to the general laws by which mankind are

governed. It is not so. They are the unanswerable

evidence of the real nature of man. They reveal

the divinity of Humanity, out of which all goodness,

all happiness, all True Greatness, can alone proceed.

They disclose susceptibilities which are universal,

which are confined to no particular race of men, to

no period of time, to no narrow circle of knowledge

and refinement but which are present wherever

two or more human beings come together, and

are strong in proportion to their virtue and

intelligence. It is, then, on the nature of man, as