|

Battle of Bushy Run: August 5-6, 1763

The

defeat at Bushy Run was the

beginning of the end for Pontiac's

Rebellion.

One

Mile to Bushy Run Station by

Robert Griffing

Timeline of Pontiac's

Rebellion 1763-1766

Included are

events that took place before Pontiac's

Rebellion and might be of interest in this

context.

Go here for

Pontiac's Rebellion in a

Nutshell

Pontiac's Rebellion in a

Nutshell

Go here for more

about

Pontiac

Pontiac

If

this timeline is too detailed,

check the

Key

Events of the Pontiac Rebellion,

which are a summary of the years

1763-1766. Key

Events of the Pontiac Rebellion,

which are a summary of the years

1763-1766.

Events Prior to Pontiac's Rebellion

1534

The French

colony

New France (Nouvelle-France, or

Gallia

Nova) is established.

New France (Nouvelle-France, or

Gallia

Nova) is established.

1535

Jacques

Cartier winters in the Huron Indian village of Stadacona (today's Quebec).

Jacques

Cartier winters in the Huron Indian village of Stadacona (today's Quebec).

1629

Quebec is

captured by the British

1632

Quebec is

restored to France by the

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

July 24, 1701

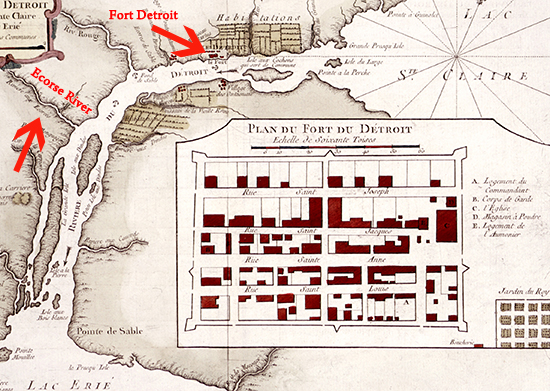

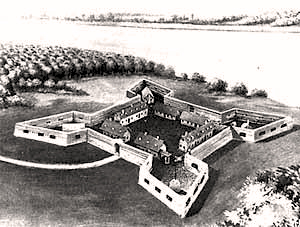

The fur-trading post Detroit, aka

Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit,

is established by

Antoine Laumet de La

Mothe Cadillac on the peninsula

between the Detroit River and Savoyard Creek.

The British will rename it later simply Fort

Detroit.

Go here for a map of

Fort Detroit in 1759

Fort Detroit in 1759

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit 1701

Burton

Historical Collection

June 19 – July 11, 1754

Albany

Congress - The British negotiate with the

Iroquois.

Sir William Johnson tries to assure

British support against the French.

Sir William Johnson tries to assure

British support against the French.

1755

Johnson is

appointed superintendent of the Iroquois

Confederacy and its allies.

1756

George Croghan (died in 1782) is appointed deputy to

Sir William Johnson, the newly

created superintendent of Indian affairs for the western nations.

1758

William Pitt

the elder selected

Jeffrey

Amherst over the heads of numerous senior

officers to fight the French. Amherst arrives in

America. He will soon become the

commander-in-chief of His Majesty's Forces in

North America.

Sir Jeffrey Amherst (1717-1797)

After the

portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1765

Library and

Archives Canada

April 30, 1759

General James Wolfe arrives from Spithead at

Halifax.

September 13, 1759

Battle of Quebec, which takes place on the

Plains of Abraham, located adjacent to the city.

British Maj. Gen. Wolfe defeats French Marquis

de Montcalm, who is mortally wounded.

Battle of Quebec, which takes place on the

Plains of Abraham, located adjacent to the city.

British Maj. Gen. Wolfe defeats French Marquis

de Montcalm, who is mortally wounded.

September 18, 1759

French Quebec surrenders to the British. This

will lead to the fall of Canada to Britain.

Early Summer 1760

Henry Gladwin is detached to assist

Colonel

Henry Bouquet in building Fort Presque Isle

(today's Erie, Pennsylvania).

Henry Gladwin is detached to assist

Colonel

Henry Bouquet in building Fort Presque Isle

(today's Erie, Pennsylvania).

September 8, 1760

At Montreal,

the last governor-general of New France, the

Marquis de Vaudreuil, surrenders his

territory to

Jeffrey Amherst. This transfer will become

official with the 1763 Treaty of Paris.

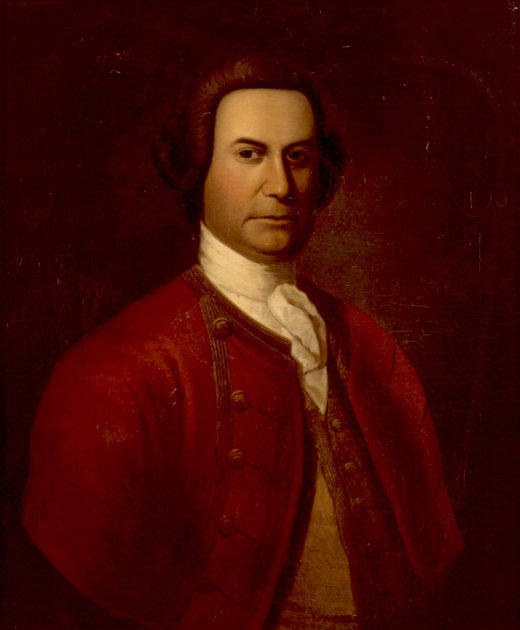

Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial,

marquis de Vaudreuil

Pierre lived 1698-1778. He was governor of

Louisiana 1743-1755,

and governor-general of Canada 1755-1760

Canadian

Museum of History

Late October 1760

Henry Gladwin is in command of Fort William

Augustus (formerly Fort Lévis, east of Prescott,

Ontario).

Henry Gladwin is in command of Fort William

Augustus (formerly Fort Lévis, east of Prescott,

Ontario).

November 27, 1760

French

Captain Francois Marie Picot de Belestre

surrenders Fort Pontchartrain de Detroit to British

Major Robert Rogers

and his 200 rangers,

who take over at Detroit and other western posts that the French

cede to the British.

On his way to Michilimackinac, Rogers meets Pontiac

and a group of Ottawa, Huron, and Potawatomi

Indians, who welcome the newcomers with a

sincerely peaceful attitude, expecting the

establishment of new commercial relations and to

be treated respectfully.

End of December

1760

Rogers departs and

Captain Donald

Campbell becomes the British commander of

Fort Detroit. Campbell

is a man who will be described as fat and

unwieldy and suffering from poor eyesight. However, he speaks

French, is relaxed, alert, competent, and most

importantly able to win the trust of Pontiac,

who was previously fighting for the French

against the British.

June 1761

Campbell reports that the new British treatment

of the natives does not go down well at all.

Apparently, the Indians incited "all the Nations from

Nova Scotia to the Illinois to take the hatchet

against the English."

September 1761

Gladwin comes to Detroit,

joining Johnson with a strong contingent of

troops.

Johnson calls a great peace conference

with the natives at

Detroit. At the meeting, Johnson, with a letter from Amherst in his

pocket forbidding him to continue to buy the

Indians' good conduct with presents, offers the

Indians presents.

Wrote Amherst to Johnson,

As to purchasing the good behavior, either

of Indians, or any others, that is what I do

not understand. When men of whatsoever race

behave ill they must be punished but not

bribed.

Although Johnson didn't say a word about Amherst's

planned change

of tradition, the Indians will soon find out when

his orders are implemented.

Sir William Johnson,

1st Baronet (1715-1774)

Arriving in America about 1738,

Irish-born Johnson settled in the Mohawk Valley.

A skilled trader

and negotiator, he was appointed Northern Indian Superintendent in

1756. Johnson was a shrewd land speculator, owner of a fortune and a

home which he humbly called Fort Johnson. In 1763, he built Johnson

Hall, his mansion Georgian style, north of Johnstown, NY.

Among other children, Johnson fathered

eight little rascals with Molly Brant, the sister of Mohawk chief

Joseph Brant.

Unlike commander in chief Jeffrey

Amherst, Johnson distributed gifts generously, and he was not above

donning war paint. Consequently, Johnson created a loyal Iroquois following. He is

credited with convincing the Iroquois to stay away from Pontiac's Rebellion.

Johnson is described as "hard-headed

and frequently self-serving, particularly regarding land claims."

This portrait is Edward L. Mooney's

oil on canvas from 1838, after the lost original by Thomas McIlworth

from 1763, which was made to hang in Johnson Hall.

New York Historical Society

Summer of 1762

A

secret council of Ottawa, Ojibwa, Huron,

Potawatomi, and others meets at Detroit. This

meeting has probably been called by Pontiac.

August 23, 1762

Campbell surrenders his command of Fort Detroit

willingly and gladly to

Major Henry Gladwin.

Campbell remains as second in command.

Major Henry Gladwin.

Campbell remains as second in command.

Also

1762

The Weas in the west and, separately, the Senecas in

the east, try to stir up a rebellion, but the

movement does not get enough traction to amount

to a revolt.

February 10, 1763

The

Treaty

of Paris is signed and officially ends the war between Britain

and France in North America. France cedes to

Britain all the mainland of North America east

of the Mississippi, excluding New Orleans and

its surroundings.

Treaty

of Paris is signed and officially ends the war between Britain

and France in North America. France cedes to

Britain all the mainland of North America east

of the Mississippi, excluding New Orleans and

its surroundings.

New France has

become British.

Flag of New

France 1534-1763

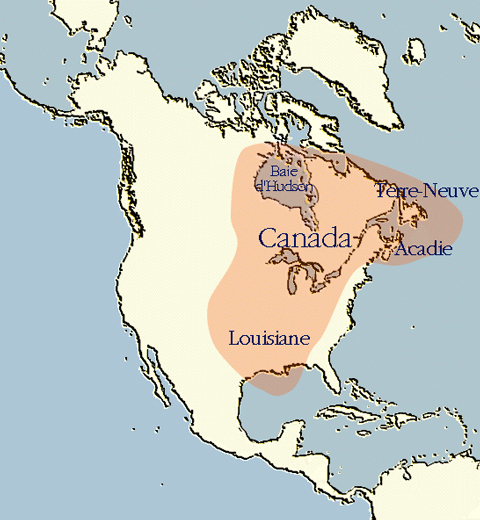

Map of New France early 18th Century

Illustrating Canada, Louisiana, Hudson Bay,

Newfoundland (Terre Neuve), Acadia (Acadie)

Ministere

de la Culture, France

The

challenge for the British is now to win the

allegiance of the Indian tribes who had been

formerly loyal allies of the French.

March 1763

The

Miami receive a war belt from the Senecas, who

still try to instigate an uprising against the

English. But still without being able to

accumulate the required momentum for a revolt.

Timeline of the Pontiac

War (April 27, 1763

- July 25, 1766)

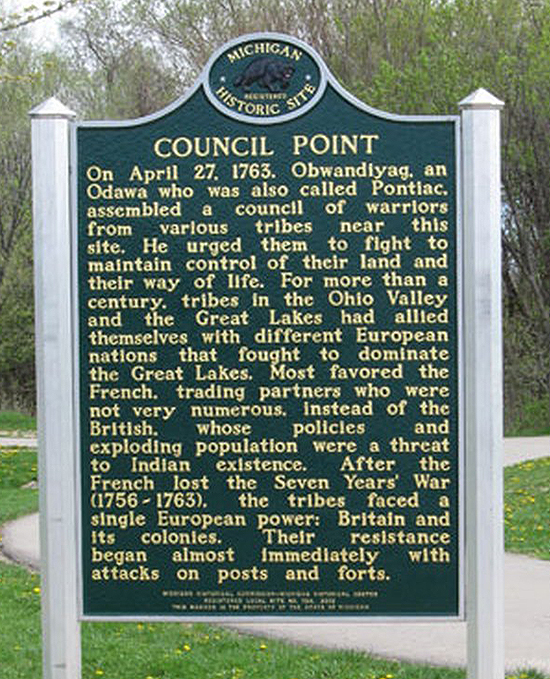

April 27, 1763

(or the Fifteenth of the Moon according to

the Indian calendar)

The intertribal War

Council, also called the

Pontiac Council,

meets along the Ecorse River, ten miles south of

Fort Detroit.

Council Point Marker

Lincoln

Park Historical Society

Why the name Ecorse? Because the

French called it Rivière aux Écorses or

Tree-Bark River) The Ecorse River flows

from the northwest into the Detroit River near

the northern tip of Turkey Island (today's

Fighting Island, Canada).

Map Location of Fort Detroit and the Ecorse

River

Histoire générale

des Voyages (Paris, 1746-1759; 15 volumes)

by Prévost / Bellin

Click to enlarge

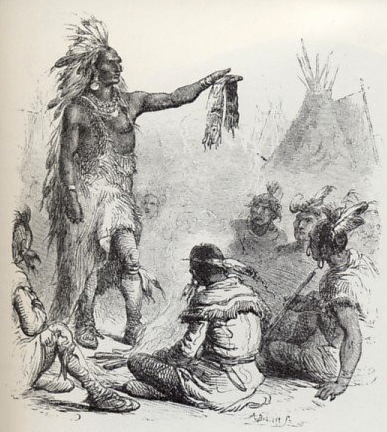

Pontiac speaks to an audience of about 500 people, among them chiefs and warriors of the Ottawa,

the Potawatomi, and the Wyandot (or Huron)

Nations. Some French people are probably

assembled as

well, considering that there are approx. 2,000

French people living at Detroit by now.

News of what

exactly the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris

are, have not arrived yet. Pontiac still

believes the French are major players and that

they will

come to his aid.

Pontiac first

recites a list of grievances against the

British. He then displays a red and purple

wampum belt, a war belt, that he

claims he has received from their French Father,

the King of France, in order to unite and fight

against the British. And, finally, Pontiac quotes the

Delaware

Prophet, who made if perfectly

clear that the white man should be driven out. Delaware

Prophet, who made if perfectly

clear that the white man should be driven out.

Pontiac Presents a War Belt at the Tribal

Council

Historical

Narratives of Early Canada

Pontiac's speech hits the target. Everyone

in the attendance is ready to follow his

lead.

Pontiac's

Rebellion begins.

Pontiac sends war

belts across the land and soon, other tribes will join.

Naturally, the center and focus of Pontiac's

operations is Detroit, the strongest British

post west of Niagara.

May 1, 1763

Pontiac and 40 warriors appear at the main gate

of Fort Detroit. They ask permission to enter so

that they could demonstrate their loyalty to the

British by dancing the calumet, or peace

dance, a variation of smoking the calumet,

or peace pipe. In actual fact, this is a

reconnaissance mission. While some of the

warriors are performing the dance, others keenly evaluate the strength and vulnerability

of the fort.

Pontiac's first

planned strike is to meet with the commander of Fort Detroit,

Major Henry Gladwin, on May 7, 1763. Pretending

to come in peace, Pontiac and his men would then, on

his signal, suddenly attack the 130 British

soldiers and officers garrisoned at the fort.

Half Length Portrait of Major

Henry Gladwin

(1730-1791)

Gladwin (city and county) in Michigan is named

after him, by the way.

Oil on

canvas by John Hall (1739-1797)

Detroit

Institute of Arts

May 6, 1763

An

informant, or informants, leak to Gladwin that the meeting with Pontiac

tomorrow is actually a

ploy to massacre the

entire garrison.

May 7, 1763

Pontiac, his fellow chiefs, and around 300

warriors meet with

Gladwin, who, in turn, has arranged a massive display of

all the firepower at his disposal, ready on his

command. Pontiac realizes that the entire fort

is on high alert, and that his plan has been

uncovered. He decides not to give the signal for the

attack.

Also on

May 7,

1763

Capt.

Charles Robertson and

Sir Robert Davers,

a British adventurer, are leading a soundings expedition in the

upper St. Clair River near today's Port Huron,

when they are attacked by a group of the Saginaw

Chippewa who are en route to join Pontiac at

Detroit. Robertson and Davers are killed along

almost all of their soldiers.

One of the

survivors, seventeen-year-old

John Rutherford, is taken captive and

will be adopted by

a Chippewa family. The Saginaw Chippewa Chief Perwash

will become John's adopted father. John will

go on to serve in the Black Watch, and to live

to age 84. Here you can read

John Rutherfurd's

Narrative of a Captivity, which

was published in the April 1958 issue of

American Heritage.

John Rutherfurd's

Narrative of a Captivity, which

was published in the April 1958 issue of

American Heritage.

May 8, 1763

Pontiac and three Ottawa chiefs go back to

Gladwin, claim there must have been a

misunderstanding, and promise to be back

shortly to smoke the pipe of peace.

May 9, 1763

Pontiac and his men return to Fort Detroit with

65 canoes. This time, Gladwin does not open the

gates. Pontiac begins the six-month

Siege of Fort Detroit. This is also called

Pontiac's Siege. Although vastly outnumbered, Gladwin and his men will be

able to hold the fort.

The unprotected

settlements around the fort, however, are quickly

ravished, stores broken into and live stock

taken. Nine British settlers and one French

settler, Francois Goslin, who was mistaken for

an Englishman, are killed. The rest is captured.

May 10, 1763

Pontiac

claims he is ready for peace negotiations and

meets with Capt. Donald Campbell,

Lieut.

George McDougall, and a few other

British soldiers at the home of

Antoine Cullerier. Pontiac

decides to hold the men hostages. Concluding to

have thus gained an upper hand in negotiations,

Pontiac sends a

French messenger to Gladwin at Fort Detroit,

demanding the same terms the British demanded

from the French, complete surrender. But Gladwin

doesn't flinch. Campbell, MacDougall, and the

others will attempt to escape

on

July

2, 1763. July

2, 1763.

Now that Fort

Detroit is cut off, the Indians who live around

the British forts, rise up.

Gladwin writes to

Jeffrey Amherst for reinforcements:

The

enemy are still masters of the country and

are likely to be so, if your Excellency does

not send a body of men to disperse them.

Amherst sends support via schooners on the

Detroit River, that are too large to be attacked

from Indian canoes. Small parties even get out

of the fort and are able to destroy buildings

the besiegers are using for cover. Amherst hands

out a new policy, Take no Indian prisoners.

May 13, 1763

A

unit of British soldiers and rangers, 96 men in

all, led by Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler, leave Fort Niagara

for Fort

Detroit, unaware of the hostilities. On

May 28, 1763,

many of them will be killed.

May 28, 1763,

many of them will be killed.

May 16, 1763

Fort Sandusky (Ohio) falls after an attack by

Ottawa and Wyandot (Huron) warriors. The entire

15 man garrison is killed, its commander

Christopher Pauli is taken prisoner

and brought to Detroit.

May 18, 1763

Pontiac calls a meeting with all habitants of

Detroit and demands that they write a letter to

Neyon de Villiers, French commander of Fort de

Chartres, to ask for help. The villagers did so,

apparently under duress, as they attached a note to

their letter to Villiers,

Neyon de Villiers, French commander of Fort de

Chartres, to ask for help. The villagers did so,

apparently under duress, as they attached a note to

their letter to Villiers,

We are forced to

submit to what the Indians demand of us. The

English are shut up, and all passages are cut

off. We cannot express our perplexity to you

[...]

May 25, 1763

Fort St. Joseph, today's Niles, Michigan, is

attacked by Potawatomi warriors, led by

Chief Washee. The fort falls,

12 of its 15 man garrison are killed. Commander

Francis Schlosser

and the rest are taken prisoner and brought to

Detroit.

May 27, 1763

Fort Miami (Fort Wayne, Indiana) falls after an

attack by the Miami tribe.

Commander Robert Holmes

and three of his men are killed, the rest of his 15 man

garrison surrenders.

May 28, 1763

The

Siege of Fort Pitt

(formerly Fort Duquesne, today's Pittsburgh) begins, led by Delaware and

Mingo warriors. Captain

Simeon Ecuyer is the

commander of the fort. During this siege, smallpox

infested blankets are given to the Indians.

Whether or not this early attempt at germ

warfare was successful and who exactly deserves

credit and blame remains a controversy.

What we do know is

that

Amherst lost his initial trivializing approach

to alleged Indian schemes ("Meer Bugbears"

Amherst to Sir William Johnson, April 3, 1763)

and wrote that the British would

Do well

to try to inoculate the Indians, by means of

blankets, as well as to try every other

method, that can serve to extirpate this

execrable race.

He asks Bouquet,

Could

it not be contrived to send the smallpox

among those disaffected tribes of Indians?

We must, on this occasion, use every

stratagem in our power to reduce them.

Memorandum by

Sir Jeffrey Amherst, May 4, 1763

Also

May 28, 1763

Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler and his men, who left Fort Niagra on

May

13, 1763, for Detroit, stop at Point Pelee

(Ontario) to camp for the night. They are

planning on crossing Lake Erie tomorrow where

they wish to deliver 139 barrels of provisions and

reinforcements at Fort Detroit. However, they are

ambushed by the Wyandot, more than half of them

are killed, and 8 of their 10 boats are taken.

The survivors escape in their remaining two

boats first to Fort Sandusky. After seeing that

the fort there has been captured as well, they

return to Fort Niagara. May

13, 1763, for Detroit, stop at Point Pelee

(Ontario) to camp for the night. They are

planning on crossing Lake Erie tomorrow where

they wish to deliver 139 barrels of provisions and

reinforcements at Fort Detroit. However, they are

ambushed by the Wyandot, more than half of them

are killed, and 8 of their 10 boats are taken.

The survivors escape in their remaining two

boats first to Fort Sandusky. After seeing that

the fort there has been captured as well, they

return to Fort Niagara.

Also

May 28, 1763

A British settlement 10 miles southeast of

Fort Pitt (today's West Newton, PA) is attacked

by the Delaware and Mingoes, led by Delaware

Chief Wolfe.

May 31, 1763

Chief

Wasson and his Chippewa (or Ojibwa) warriors

from the Saginaw River arrive at Detroit. Wasson

and Pontiac resolve, instead of tightening the

siege of Fort Detroit, to focus on preventing

British relief forces from reaching the fort.

French citizens of Detroit are now supplying the

fort with provisions.

June 1, 1763

Fort Ouitenon (5 miles southwest of today's Lafayette, Indiana) falls

without a shot. The

attacking Weas, Kickapoos, and Mascoutens simply

walk in and take

the 20 man garrison prisoner. Commander

Lieutenant Edward Jenkins wisely choses to

surrender. He and his men will be exchanged for

enemy prisoners.

June 2, 1763

- Fort Michilimackinac (Northern Michigan) is

attacked by Chippewa (Ojibwa) and Sauks warriors. The

fort falls, 21 of the 35 man garrison are

killed. The fort's commander,

Captain George Etherington, and his deputy,

Lieutenant William Leslye are taken prisoner. Among the killed is

Lieutenant John Jamet, who had come with a small

unit from St. Mary's (today's Sault Ste. Marie).

This attack was a sneaky one. News from

the outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion hasn't yet

arrived at this fort. The Chippewa who live in

the neighborhood, however, were well-informed.

They gather just outside the fort, and start

playing a game of baggatiway, or lacrosse.

Suddenly the ball is thrown over the wall, the

players are chasing after it while passing their

women and taking weapons from underneath their

blankets. The entire attack is over within

minutes.

Also on

June 2, 1763

Fort

Ligonier (Pennsylvania) is attacked by Delaware,

Shawnee, and Mingo warriors. This attack is

unsuccessful. No casualties.

June 4, 1763

Ottawa

warriors, led by Chief Okinochumake, take

the Fort Michilimackinac prisoners from the

Chippewa. The prisoners will later be brought to

Montreal for prisoner exchange.

June 8, 1763

Chief Sekahos and his Chippewa (or Ojibwa)

warriors from the Thames River arrive at

Detroit.

By now, Pontiac

leads more than 850 warriors: approx. 250 Ottawa, 150

Potawatomi, 50 Huron (or Wyandotte), 250 Saginaw

Chippewa (or Ojibwa), and 170 Thames River

Chippewa (or Ojibwa).

June 16, 1763

Fort Venango (or Fort Machault, today's

Franklin, Pa) falls. The attacking Seneca

warriors kill the entire 15 man garrison,

including its commander

Lieutenant Francis

Gordon, and burn the fort to the ground.

June 18, 1763

Fort Le Boeuf (today's Waterford, Pa) falls

after an attack by Seneca warriors. Two men are

killed, the fort destroyed. The survivors, including its commander

George Price, escape to Fort Venango. Seeing

that Fort Venango has been taken as well, they

move on to Fort

Pitt.

Also on

June 18,

1763

Father Dujonois, the Jesuit missionary

among the northern Ottawa,

Chief Kinonchamek (who is

the son of the great Chippewa

Chief Minavavana),

seven Ottawa, and eight Chippewa warriors arrive

at Detroit. They bring Pontiac the good news of

the capture of Fort Michilimackinac, see

June

2, 1763. June

2, 1763.

June 19, 1763

The

Siege of Fort Presque Isle (today's Erie,

Pa) begins. A massive crowd of over 250 Ottawa,

Chippewa (or Ojibwa), Wyandot (or Huron), and Seneca warriors will

stick around until June 22.

June 21, 1763

At

Fort Edward Augustus (or Fort LeBaye, today's

Green Bay, Wisconsin) the fort's commander,

Lieutenant James Gorrell receives a message from

Captain Etherington, telling him to abandon the

isolated fort and to get to L'Arbe Croche (Cross

Village).

Gorrell and his men leave with the quickness.

June 22, 1763

The

Siege of Fort Presque Isle ends when the 60

man garrison surrenders. Three men are killed,

the rest, including the fort's commander

John

Christie, are taken prisoner and brought to

Detroit. The fort is destroyed.

July 2, 1763

Campbell and MacDougall, still Pontiac's

hostages, resolve to escape. McDougall and a few

other British prisoners make it into the forest,

but Captain Donald Campbell, slowed down by some

extra pounds and his very bad eye-sight, prefers to stay

put.

July 4, 1763

Captain Donald Campbell is tomahawked by Saginaw

Chippewa Chief Wasson to avenge the killing of

his nephew by British soldiers. The British are

outraged. In effect, Pontiac's men had killed a

British envoy sent to negotiate peace. Amherst

is fuming, and puts a 100-pounds reward on

Pontiac's head.

Fort Detroit has

now a French militia. This is the first time

since the surrender of New France in 1760, that

the French at

Detroit are officially carrying arms again.

James

Sterling, born in Ireland and now a

prominent trader at Fort Detroit, is made

captain of the French militia. Go here for more

about the

James Sterling Letter Book.

James Sterling Letter Book.

July 6, 1763

The

Ottawa try to set fire to the British ships that

are moored at Fort Detroit by settings rafts on fire

and sending them downstream. This attempt is

consistently unsuccessful and will soon be

abandoned.

Here is an excerpt from a letter

written at Fort Detroit on this day:

We have

been besieged here two months by six hundred

Indians. We have been upon the watch night

and day, from the commanding officer to the

lowest soldier, since the 8th of May. We

have not had our clothes off, nor slept a

night since the siege began. We shall

continue so till we have a reinforcement.

Then we hope to give a good account of the

savages. Their camp lies about a mile and a

half from the fort. That is the nearest they

choose to come now.

For the

first two or three days we were attacked by

three or four hundred of them. But we gave

them so warm a reception that they do not

care for coming to see us, though they now

and then get behind a barn or a house and

fire at us at three or four hundred yards

distance. Day before yesterday we killed a

chief and three others, and wounded some

more. Yesterday we went up and our sloop and

battered their cabins in such a matter that

they are glad to keep farther off.

Mid-July 1763

A

prisoner exchange brokered between Wyandot

(Huron) and Potawatomi and Major Henry Gladwin

goes awry when the natives try to withhold

some of their British prisoners.

July 14, 1763

Jacques Cavallier, age 30, is killed

by a Potawatomi sniper while standing sentinel at Fort Detroit. Cavallier was a

member of the French milita at the fort. He is

one of only two Frenchmen who will be killed

during the Siege of Fort Detroit.

July 29, 1763

This morning, a

relief force of 260 troops from the 55th and the

80th Regiments, led

by Captain John Dalyell (aka General Amherst's

right hand), and 20 independent rangers, led by

Major Robert Rogers,

arrives at Detroit with provisions and

ammunition. Dalyell is eager to engage

in combat. Gladwin will later remember:

On the

31st, Captain Dallyell requested, as a

particular favor, that I would give him the

command of a party in order to attempt the

surprizal of Pontiac's camp under cover of

the night. To which I answered, that I was

of the opinion, that Pontiac was too much on

his guard to effect it. He then said he

thought I had it in my power to give him a

stroke, and that if I did not attempt it

now, he would run off, and I should never

have another opportunity. This induced me to

give in to the scheme, contrary to my

judgment.

Major Gladwyn

to Sir Jeffrey Amherst, Detroit, August 8,

1763

July 31, 1763

Battle of Bloody Run

- a six-hour engagement and one of the largest victories for Pontiac.

At 2:30 AM,

Dalyell and 247 troops put boots on the road and

march from Fort Detroit to

surprise Pontiac's camp. When they get close to

the bridge at Parent's Creek / Jean Baptiste

Meloche's farm, they are ambushed from three

sides by Pontiac's men, a combined force of

Ottawa, Chippewa, and Wyandot.

Frenchman

Meloche, by the way, is a friend of Pontiac. And

yes, Pontiac's French

friends had informed him of this planned

surprise attack.

Map Location Battleground Bloody Run

The Battle

of Bloody Run was fought at Parent's Creek

(French: Riviere Parent), later it became

Bloody Run

Click map

to enlarge

The British suffer

150 casualties, including Dalyell. Some are

taken prisoner, the rest retreats with the

wounded to the fort.

Lincoln Park Historical Society tells us,

A

remnant of the creek is found in Elmwood

Cemetery today; an historical marker

commemorating the ‘Battle of Bloody Run’ is

located at the entrance to the Players Club

building at 3321 East Jefferson Avenue near

Mt. Elliott.

Pontiac's great

victory at Bloody Run had two effects. More

Indians were joining his cause and more resolve

toughened the British.

August 1, 1763

Large groups of Delaware and

Shawnee warriors leave the Siege of Fort Pitt

to intercept an approaching

British force led by Colonel Henry Bouquet. This

they will, in the Battle of Busy Run, on August

5, 1763.

August 2, 1763

Bouquet’s troops, about 500 men, 300 of them

members of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, The

Black Watch, reach Fort Ligonier. They rest for

two days, and transfer the flour provisions for

Fort Pitt from the wagon barrels they had been

using to 340 packhorses.

August 5, 1763

The

Battle of Bushy Run begins. The British, led by Col.

Henry Bouquet (1719-1765) arrive from Carlisle

to relieve Fort Pitt. Thirty miles southeast of

Fort Pitt, a well-camouflaged group of Delaware,

Shawnee, Mingo, and Wyandot warriors launch a

frontal attack on Bouquet's advanced guard. The

first day of fighting was won by the Indians.

August 6, 1763

The

Battle of Bushy Run ends. Colonel Henry Bouquet (an expert of

warfare against irregular opponents) defeats

the Indians thanks to a surprise strategy. Two

British companies pretended to withdraw, luring

Pontiac's men out of their cover and into a lethal

crossfire. This is the first time that the

British have fought the enemy on its own terms

and won. End of battle. British Casualties: 50

killed, 60 wounded.

Sketch of the Battle of Bushy Run

Click to enlarge

This is the

beginning of the end of Pontiac's War. His

rebellion will lose momentum in part because of

today's defeat, in part because of the stalemate

at Detroit, and in part because the

Indians will soon have to move with the changing

season and retreat to their winter hunting

grounds.

August 10, 1763

Bouquet and his men reach Fort Pitt.

The Siege of Fort Pitt

ends.

September 1763

A copy of the 1763 Paris peace

treaty reaches Fort de Chartres on the

Mississippi River, Illinois Country. After

contemplation, its French commander,

Major

Pierre Joseph Neyon de Villiers, decides to encourage the Indians to become peaceful with

the British, and writes a letter addressed to

all Indians:

My Dear

Children... The great day has come ... the

Master of Life has inspired the Great King

of the French and him of the English to make

peace between them, sorry to see the blood

of men spilt so long. ... What joy you will

have in seeing the French and English

smoking with the same pipe and eating out of

the same spoon and finally living like

brethren. ... Leave off then, my Dear

Children, from spilling the blood of your

brethren, the English. Our hearts are now

but one. You cannot at present strike the

one without having the other for your enemy

also.

By the way, what's a Frenchman doing still commanding

a fort?

Neyon de Villiers was the French commander of

Illinois. Now his turf was officially under

British rule, but with no British troops in

sight. The Fort de Chartres will have a transfer

ceremony on October 10, 1765, when finally

British troops of the 42nd Royal Highland

Regiment will take over.

The French Stone Fort de Chartres

Illinois

Historic Preservation Agency

September 3 and 4, 1763

When the

schooner Huron, loaded with provisions from Fort

Niagara, is moored in the lower Detroit River

near Turkey Island (today's fighting Island),

approx. 340 Ottawa and Chippewa warriors attack.

Two British aboard are killed. The ship's

captain, Captain Horsey, is one of them.

September 9, 1763

Amherst to Henry Gladwin:

By a

formal letter I had offered a reward of 100

pounds to the person who should kill

Pontiac. If you think another 100 could be

inducement for a daring fellow to attempt

the death of that villain, I will add it

with pleasure. His death will be some small

satisfaction for the loss of poor Dalyell.

September 14, 1763

Battle of Devil's Hole

(near Fort Niagara, NY). Seneca warriors attack

a lightly escorted British wagon train that

rolls north along the Niagara Gorge, between Fort Schlosser and Fort

Niagara. The wagons were returning to the Lower

Landing (Lewiston) for another load of

provisions. Just when the convoy approaches the

creek flowing into Devil's Hole, they rumble

across a small wooden span, later known as

Bloody Bridge. Here the Seneca attack. Well aware of the importance of the

British supply lines, they destroy the draft

animals and throw harness and wagons into the

gorge.

Alarmed by the

gunfire, British troops of the 80th Regiment of

Foot, who are encamped at the Lower Landing two

miles down the river, rush to the convoy's aid,

but are ambushed as well. The troops are led by

Lieutenant George Campbell. They were on their

way to Detroit. In this second ambush, the

Seneca kill 80 British troops, slightly north

of Devil's Hole in what will become known as

Campbell's Defeat. Only 8 wounded men

make it back to Fort Niagara.

This is bloodiest battle of the Pontiac War,

hence also called the Devil's Hole Massacre. It will be weeks

before the British will again be able to supply

Detroit with its necessary provisions.

This is the

closest Fort Niagara comes to being attacked.

The fort itself was never actually threatened.

October 7, 1763

Royal Proclamation by British King George III,

aka the

Proclamation

of 1763. Proclamation

of 1763.

The Proclamation

of 1763, is a remarkable decree. For example, it

acknowledges that "great Frauds and Abuses have

been committed in purchasing Lands of the

Indians."

Here is an

excerpt:

And We do further

declare it to be Our Royal Will and Pleasure,

for the present as aforesaid, to reserve under

our Sovereignty, Protection, and Dominion, for

the use of the said Indians, all the Lands and

Territories not included within the Limits of

Our said Three new Governments, or within the

Limits of the Territory granted to the Hudson's

Bay Company, as also all the Lands and

Territories lying to the Westward of the Sources

of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the

West and North West as aforesaid.

In other words, from now on, the

territory between the Appalachian Mountains and

the Mississippi River and from the Great Lakes

more or less down to the Gulf of Mexico, is reserved exclusively

for the Indians. The British colonies in North

America have a firm western boundary. Those whites who have already

settled beyond this border line are ordered to remove themselves.

Although this act will be ignored by future

settlers and law makers, this is the first time

in North American colonial history that Indian

property rights are officially recognized.

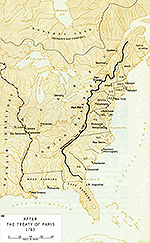

Here is the map

1763 North America

after the Treaty of Paris (February

10, 1763)

and after the Royal

Proclamation (October 7, 1763)

October 29, 1763

Pontiac is shown Neyon de

Villier's letter to all Indians in former New France.

He realizes that his former French allies have

cut their ties.

However, he will

not give up and will arrange a meeting with

Neyon on

April 15, 1764. April 15, 1764.

October 31, 1763

Pontiac lifts the

Siege of

Fort Detroit and withdraws to the Maumee River.

He sues for peace, and writes to Gladwin:

My

Brother, the word that my father has sent to

make peace I accept; all of my young men

have buried their hatchets.

I think

that yon will forget the bad things that

have happened this past while. For my

part I shall forget, which you can show me

how to do, in order to think only of good

things.

I, the

Ojibwas, the Hurons, we must go to speak to

you when you will ask us. Reply to us. I am

sending you the adviser so that you may see

him. If you are indeed like me you will give

me a reply.

I send

you greetings.

Gladwin replies that he would forward

Pontiac's message to the general.

December 1763

Conestoga Massacre, also called the

Paxton Boys Uprising, near Lancaster, PA.

Fifty-seven drunken frontiersmen from Paxton slaughter 20 peaceful

and defenseless Conestoga Indians, and will get away with it.

April 15, 1764

Neyon receives Pontiac, who asks for his support

against the British. Neyon declines, referring to the peace treaty

between Britain and France.

August 27, 1764

Colonel John Bradstreet arrives

from Niagara with his expedition that was sent to lift the siege of

Detroit. Bradstreet encounters no opposition.

Bradstreet also has instructions to

punish the natives, but he prefers to make treaties with hostile

tribes. This will not sit well with his superior, Major-General

Thomas Gage.

Also on

August 27, 1764

Shawnee

chief Charlot Kaske seeks in vain the military support of

Louis Groston de Saint-Ange de Bellerive, commander at Vincennes.

Late October 1764

Bradstreet and his

men attempt to return across Lake Erie. Storms cost the lives of

many of his men.

December 1764

The Shawnee appeal to

the French authorities in New Orleans to help them out in their

fight against the British.

February 1765

Once again, the

Shawnee ask the French at New Orleans for help, still without success.

April 18, 1765

Peace talks between Pontiac and

Louis Groston de Saint-Ange de Bellerive and

Lieutenant

Alexander Fraser.

July 1765

At Fort Ouiatenon, now in

native hands, Colonel George Croghan,

Johnson's chief deputy supervisor of Natives affairs for the English

colonies of America, and Pontiac

come to an agreement to end the uprising. A preliminary settlement is signed. Pontiac

points out that the French submission to the British has

nothing to do with the Indian Nations, as the French had not

conquered them. Thus, the British should not assume the submission

of the natives.

August 17, 1765

Croghan and Pontiac are

meeting with chiefs of the Ottawa, Ojibwa, Huron, and Potawatomi to

ratify this agreement. Not everyone, however, is convinced.

July 25, 1766

The Algonkian chiefs and Pontiac meet at Fort

Ontario (Oswego, NY) to sign a final peace treaty.

Sir William Johnson,

British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, presides. He lets Pontiac

speak for all of them, which further alienates them.

Pontiac's

Rebellion ends.

Among some Indians, Pontiac has by now acquired a reputation of

having sold out his people to the British. A rumor that he is on

British payroll doesn't help.

Pontiac sticks to the treaty with the

British. His village exiles him.

Skirmishes between Indians and whites continue here and there

but Pontiac stays true to his word. He is done fighting and resumes

his life as an independent fur trader.

March 30, 1769

Pontiac arrives at

Cahokia, Illinois.

April 20, 1769

At Cahokia, Pontiac

enters the store of Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan, accepts a drink, leaves the store,

and is attacked and killed by a Peoria Indian.

It is debated whether the killing was

motivated by individual disgruntlement, tribal disgruntlement, or

whether it was a paid assassination.

John Wilkins, commander of Fort

Cavendish (formerly Fort de Chartres) immediately orders a local

businessman to bury the victim. No one knows where Pontiac is

buried.

Later, Ojibwa

Chief Minweweh will take revenge

and kill two employees of Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan, for a lack

of a better target.

More History

|