|

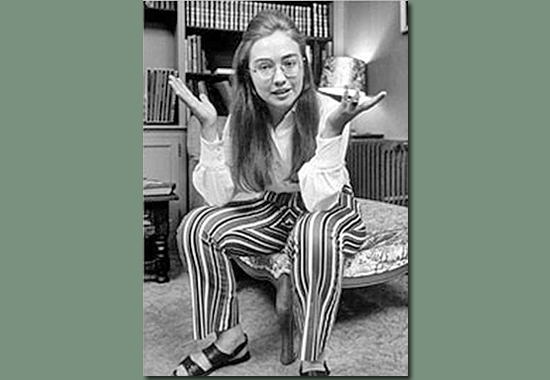

MISS HILLARY D. RODHAM - CLASS OF

'69

Wellesley Student Commencement

Speech

It follows the full text transcript of

Hillary Rodham's Wellesley Student Commencement

Speech, delivered at Wellesley, MA — May 31, 1969.

Ruth M. Adams:

[Ninth president of Wellesley College]

In addition to

inviting Senator Brooke to speak to them this

morning, the Class of '69 has expressed a desire

to speak to them and for them at this morning's

commencement. There was no debate so far as I

could ascertain as to who their spokesman was to

be — Miss Hillary Rodham.

Member of this

graduating class, she is a major in political

science and a candidate for the degree with

honors. In four years she has combined academic

ability with active service to the College, her

junior year having served as a Vil Junior, and

then as a member of Senate and during the past

year as President of College Government and

presiding officer of College Senate. She is also

cheerful, good humored, good company, and a good

friend to all of us and it is a great pleasure

to present to this audience Miss Hillary Rodham.

Hillary Rodham:

I am very glad

that Miss Adams made it clear that what I am

speaking for today is all of us — the 400 of us

— and I find myself in a familiar position, that

of reacting, something that our generation has

been doing for quite a while now.

We're not in the

positions yet of leadership and power, but we do

have that indispensable task of criticizing and

constructive protest and I find myself reacting

just briefly to some of the things that Senator

Brooke said. This has to be brief because I do

have a little speech to give.

Part of the

problem with empathy with professed goals is

that empathy doesn't do us anything. We've had

lots of empathy; we've had lots of sympathy, but

we feel that for too long our leaders have used

politics as the art of making what appears to be

impossible, possible.

What does it mean

to hear that 13.3% of the people in this country

are below the poverty line? That's a percentage.

We're not interested in social reconstruction;

it's human reconstruction. How can we talk about

percentages and trends? The complexities are not

lost in our analyses, but perhaps they're just

put into what we consider a more human and

eventually a more progressive perspective.

The question about

possible and impossible was one that we brought

with us to Wellesley four years ago. We arrived

not yet knowing what was not possible.

Consequently, we expected a lot. Our attitudes

are easily understood having grown up, having

come to consciousness in the first five years of

this decade — years dominated by men with

dreams, men in the civil rights movement, the

Peace Corps, the space program — so we arrived

at Wellesley and we found, as all of us have

found, that there was a gap between expectation

and realities.

But it wasn't a

discouraging gap and it didn't turn us into

cynical, bitter old women at the age of 18. It

just inspired us to do something about that gap.

What we did is often difficult for some people

to understand. They ask us quite often: "Why, if

you're dissatisfied, do you stay in a place?"

Well, if you didn't care a lot about it you

wouldn't stay. It's almost as though my mother

used to say, "I'll always love you but there are

times when I certainly won't like you."

Our love for this

place, this particular place, Wellesley College,

coupled with our freedom from the burden of an

inauthentic reality allowed us to question basic

assumptions underlying our education. Before the

days of the media orchestrated demonstrations,

we had our own gathering over in Founder's

parking lot. We protested against the rigid

academic distribution requirement. We worked for

a pass-fail system. We worked for a say in some

of the process of academic decision making. And

luckily we were in a place where, when we

questioned the meaning of a liberal arts

education there were people with enough

imagination to respond to that questioning.

So we have made

progress. We have achieved some of the things

that initially saw as lacking in that gap

between expectation and reality. Our concerns

were not, of course, solely academic as all of

us know. We worried about inside Wellesley

questions of admissions, the kind of people that

should be coming to Wellesley, the process for

getting them here. We questioned about what

responsibility we should have both for our lives

as individuals and for our lives as members of a

collective group.

Coupled with our concerns for the Wellesley

inside here in the community were our concerns

for what happened beyond Hathaway House. We

wanted to know what relationship Wellesley was

going to have to the outer world. We were lucky

in that one of the first things Miss Adams did

was to set up a cross-registration with MIT

because everyone knows that education just can't

have any parochial bounds any more. One of the

other things that we did was the Upward Bound

program. There are so many other things that we

could talk about; so many attempts, at least the

way we saw it, to pull ourselves into the world

outside. And I think we've succeeded. There will

be an Upward Bound program, just for one

example, on the campus this summer.

Many of the issues that I've mentioned — those

of sharing power and responsibility, those of

assuming power and responsibility have been

general concerns on campuses throughout the

world. But underlying those concerns there is a

theme, a theme which is so trite and so old

because the words are so familiar. It talks

about integrity and trust and respect.

Words have a funny

way of trapping our minds on the way to our

tongues but there are necessary means even in

this multi-media age for attempting to come to

grasps with some of the inarticulate maybe even

inarticulable things that we're feeling. We are,

all of us, exploring a world that none of us

even understands and attempting to create within

that uncertainty. But there are some things we

feel, feelings that our prevailing, acquisitive,

and competitive corporate life, including

tragically the universities, is not the way of

life for us. We're searching for more immediate,

ecstatic and penetrating mode of living. And so

our questions, our questions about our

institutions, about our colleges, about our

churches, about our government continue. The

questions about those institutions are familiar

to all of us. We have seen heralded across the

newspapers. Senator Brooke has suggested some of

them this morning. But along with using these

words — integrity, trust, and respect — in

regard to institutions and leaders we're perhaps

harshest with them in regard to ourselves.

Every protest, every dissent, whether it's an

individual academic paper, Founder's parking lot

demonstration, is unabashedly an attempt to

forge an identity in this particular age. That

attempt at forging for many of us over the past

four years has meant coming to terms with our

humanness. Within the context of a society that

we perceive — now we can talk about reality, and

I would like to talk about reality sometime,

authentic reality, inauthentic reality, and what

we have to accept of what we see — but our

perception of it is that it hovers often between

the possibility of disaster and the potentiality

for imaginatively responding to men's needs.

There's a very strange conservative strain that

goes through a lot of New Left, collegiate

protests that I find very intriguing because it

harkens back to a lot of the old virtues, to the

fulfillment of original ideas. And it's also a

very unique American experience. It's such a

great adventure. If the experiment in human

living doesn't work in this country, in this

age, it's not going to work anywhere.

But we also know that to be educated, the goal

of it must be human liberation. A liberation

enabling each of us to fulfill our capacity so

as to be free to create within and around

ourselves. To be educated to freedom must be

evidenced in action, and here again is where we

ask ourselves, as we have asked our parents and

our teachers, questions about integrity, trust,

and respect.

Those three words

mean different things to all of us. Some of the

things they can mean, for instance: Integrity,

the courage to be whole, to try to mold an

entire person in this particular context, living

in relation to one another in the full poetry of

existence. If the only tool we have ultimately

to use is our lives, so we use it in the way we

can by choosing a way to live that will

demonstrate the way we feel and the way we know.

Integrity — a man like Paul Santmire. Trust.

This is one word that when I asked the class at

our rehearsal what it was they wanted me to say

for them, everyone came up to me and said "Talk

about trust, talk about the lack of trust both

for us and the way we feel about others. Talk

about the trust bust." What can you say about

it? What can you say about a feeling that

permeates a generation and that perhaps is not

even understood by those who are distrusted? All

they can do is keep trying again and again and

again. There's that wonderful line in East Coker

by Eliot about there's only the trying, again

and again and again; to win again what we've

lost before.

And then respect. There's that mutuality of

respect between people where you don't see

people as percentage points. Where you don't

manipulate people. Where you're not interested

in social engineering for people. The struggle

for an integrated life existing in an atmosphere

of communal trust and respect is one with

desperately important political and social

consequences. And the word "consequences" of

course catapults us into the future. One of the

most tragic things that happened yesterday, a

beautiful day, was that I was talking to woman

who said that she wouldn't want to be me for

anything in the world. She wouldn't want to live

today and look ahead to what it is she sees

because she's afraid. Fear is always with us but

we just don't have time for it. Not now.

There are two people that I would like to thank

before concluding. That's Ellie Acheson, who is

the spearhead for this, and also Nancy Scheibner

who wrote this poem which is the last thing that

I would like to read:

My entrance

into the world of so-called "social

problems"

Must be with quiet laughter, or not at all.

The hollow men of anger and bitterness

The bountiful ladies of righteous

degradation

All must be left to a bygone age.

And the purpose of history is to provide a

receptacle

For all those myths and oddments

Which oddly we have acquired

And from which we would become unburdened

To create a newer world

To transform the future into the present.

We have no need of false revolutions

In a world where categories tend to

tyrannize our minds

And hang our wills up on narrow pegs.

It is well at every given moment to seek the

limits in our lives.

And once those limits are understood

To understand that limitations no longer

exist.

Earth could be fair. And you and I must be

free

Not to save the world in a glorious crusade

Not to kill ourselves with a nameless

gnawing pain

But to practice with all the skill of our

being

The art of making possible.

More History

|