|

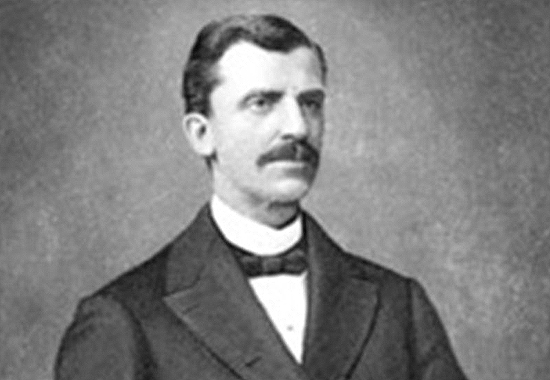

INSPIRATIONAL SPEAKER RUSSELL H.

CONWELL

Acres of Diamonds

|

I am astonished

that so many people should care to hear this |

story over again.

Indeed, this lecture has become a study in

psychology; it often breaks all rules of

oratory, departs from the precepts of rhetoric,

and yet remains the most popular of any lecture

I have delivered in the fifty-seven years of my

public life.

I have sometimes

studied for a year upon a lecture and made

careful research, and then presented the lecture

just once never delivered it again. I put too

much work on it. But this had no work on it

thrown together perfectly at random, spoken

offhand without any special preparation, and it

succeeds when the thing we study, work over,

adjust to a plan, is an entire failure.

The "Acres of Diamonds" which I have mentioned

through so many years are to be found in this

city, and you are to find them. Many have found

them. And what man has done, man can do. I could

not find anything better to illustrate my

thought than a story I have told over and over

again, and which is now found in books in nearly

every library.

In 1870 we went down the Tigris River. We hired

a guide at Bagdad to show us Persepolis, Nineveh

and Babylon, and the ancient countries of

Assyria as far as the Arabian Gulf. He was well

acquainted with the land, but he was one of

those guides who love to entertain their

patrons; he was like a barber that tells you

many stories in order to keep your mind off the

scratching and the scraping. He told me so many

stories that I grew tired of his telling them

and I refused to listen looked away whenever

he commenced; that made the guide quite angry.

I remember that toward evening he took his

Turkish cap off his head and swung it around in

the air. The gesture I did not understand and I

did not dare look at him for fear I should

become the victim of another story. But,

although I am not a woman, I did look, and the

instant I turned my eyes upon that worthy guide

he was off again. Said he, "I will tell you a

story now which I reserve for my particular

friends!" So then, counting myself a particular

friend, I listened, and I have always been glad

I did.

He said there once lived not far from the River

Indus an ancient Persian by the name of Al Hafed.

He said that Al Hafed owned a very large farm

with orchards, grain fields and gardens. He was

a contented and wealthy man contented because

he was wealthy, and wealthy because he was

contented. One day there visited this old farmer

one of those ancient Buddhist priests, and he

sat down by Al Hafed's fire and told that old

farmer how this world of ours was made.

He said that this world was once a mere bank of

fog, which is scientifically true, and he said

that the Almighty thrust his finger into the

bank of fog and then began slowly to move his

finger around and gradually to increase the

speed of his finger until at last he whirled

that bank of fog into a solid ball of fire, and

it went rolling through the universe, burning

its way through other cosmic banks of fog, until

it condensed the moisture without, and fell in

floods of rain upon the heated surface and

cooled the outward crust. Then the internal

flames burst through the cooling crust and threw

up the mountains and made the hills and the

valleys of this wonderful world of ours. If this

internal melted mass burst out and cooled very

quickly it became granite; that which cooled

less quickly became silver; and less quickly,

gold; and after gold diamonds were made. Said

the old priest, "A diamond is a congealed drop

of sunlight."

This is a scientific truth also. You all know

that a diamond is pure carbon, actually

deposited sunlight and he said another thing I

would not forget: he declared that a diamond is

the last and highest of God's mineral creations,

as a woman is the last and highest of God's

animal creations. I suppose that is the reason

why the two have such a liking for each other.

And the old priest told Al Hafed that if he had

a handful of diamonds he could purchase a whole

country, and with a mine of diamonds he could

place his children upon thrones through the

influence of their great wealth.

Al Hafed heard all about diamonds and how much

they were worth, and went to his bed that night

a poor man not that he had lost anything, but

poor because he was discontented and

discontented because he thought he was poor. He

said: "I want a mine of diamonds!" So he lay

awake all night, and early in the morning sought

out the priest.

Now I know from experience that a priest when

awakened early in the morning is cross. He awoke

that priest out of his dreams and said to him,

"Will you tell me where I can find diamonds?"

The priest said, "Diamonds? What do you want

with diamonds?" "I want to be immensely rich,"

said Al Hafed, "but I don't know where to go."

"Well," said the priest, "if you will find a

river that runs over white sand between high

mountains, in those sands you will always see

diamonds." "Do you really believe that there is

such a river?" "Plenty of them, plenty of them;

all you have to do is just go and find them,

then you have them." Al Hafed said, "I will go."

So he sold his farm, collected his money at

interest, left his family in charge of a

neighbor, and away he went in search of

diamonds.

He began very properly, to my mind, at the

Mountains of the Moon. Afterwards he went around

into Palestine, then wandered on into Europe,

and at last, when his money was all spent, and

he was in rags, wretchedness and poverty, he

stood on the shore of that bay in Barcelona,

Spain, when a tidal wave came rolling in through

the Pillars of Hercules and the poor, afflicted,

suffering man could not resist the awful

temptation to cast himself into that incoming

tide, and he sank beneath its foaming crest,

never to rise in this life again.

When that old guide had told me that very sad

story, he stopped the camel I was riding and

went back to fix the baggage on one of the other

camels, and I remember thinking to myself, "Why

did he reserve that for his particular friends?"

There seemed to be no beginning, middle or end

nothing to it. That was the first story I ever

heard told or read in which the hero was killed

in the first chapter. I had but one chapter of

that story and the hero was dead.

When the guide came back and took up the halter

of my camel again, he went right on with the

same story. He said that Al Hafed's successor

led his camel out into the garden to drink, and

as that camel put its nose down into the clear

water of the garden brook Al Hafed's successor

noticed a curious flash of light from the sands

of the shallow stream, and reaching in he pulled

out a black stone having an eye of light that

reflected all the colors of the rainbow, and he

took that curious pebble into the house and left

it on the mantel, then went on his way and

forgot all about it.

A few days after that, this same old priest who

told Al Hafed how diamonds were made, came in to

visit his successor, when he saw that flash of

light from the mantel. He rushed up and said,

"Here is a diamond here is a diamond! Has Al

Hafed returned?" "No, no; Al Hafed has not

returned and that is not a diamond; that is

nothing but a stone; we found it right out here

in our garden." "But I know a diamond when I see

it," said he; "that is a diamond!"

Then together they rushed to the garden and

stirred up the white sands with their fingers

and found others more beautiful, more valuable

diamonds than the first, and thus, said the

guide to me, were discovered the diamond mines

of Golconda, the most magnificent diamond mines

in all the history of mankind, exceeding the

Kimberley in its value. The great Kohinoor

diamond in England's crown jewels and the

largest crown diamond on earth in Russia's crown

jewels, which I had often hoped she would have

to sell before they had peace with Japan, came

from that mine, and when the old guide had

called my attention to that wonderful discovery

he took his Turkish cap off his head again and

swung it around in the air to call my attention

to the moral.

Those Arab guides have a moral to each story,

though the stories are not always moral. He said

had Al Hafed remained at home and dug in his own

cellar or in his own garden, instead of

wretchedness, starvation, poverty and death a

strange land, he would have had "acres of

diamonds" for every acre, yes, every shovelful

of that old farm afterwards revealed the gems

which since have decorated the crowns of

monarchs. When he had given the moral to his

story, I saw why he had reserved this story for

his "particular friends." I didn't tell him I

could see it; I was not going to tell that old

Arab that I could see it. For it was that mean

old Arab's way of going around such a thing,

like a lawyer, and saying indirectly what he did

not dare say directly, that there was a certain

young man that day traveling down the Tigris

River that might better be at home in America. I

didn't tell him I could see it.

I told him his story reminded me of one, and I

told it to him quick. I told him about that man

out in California, who, in 1847, owned a ranch

out there. He read that gold had been discovered

in Southern California, and he sold his ranch to

Colonel Sutter and started off to hunt for gold.

Colonel Sutter put a mill on the little stream

in that farm and one day his little girl brought

some wet sand from the raceway of the mill into

the house and placed it before the fire to dry,

and as that sand was falling through the little

girl's fingers a visitor saw the first shining

scales of real gold that were ever discovered in

California; and the man who wanted the gold had

sold his ranch and gone away, never to return.

I delivered this lecture two years ago in

California, in the city that stands near that

farm, and they told me that the mine is not

exhausted yet, and that a one- third owner of

that farm has been getting during these recent

years twenty dollars of gold every fifteen

minutes of his life, sleeping or waking. Why,

you and I would enjoy an income like that!

But the best illustration that I have now of

this thought was found here in Pennsylvania.

There was a man living in Pennsylvania who owned

a farm here and he did what I should do if I had

a farm in Pennsylvania - he sold it. But before

he sold it he concluded to secure employment

collecting coal oil for his cousin in Canada.

They first discovered coal oil there. So this

farmer in Pennsylvania decided that he would

apply for a position with his cousin in Canada.

Now, you see, the farmer was not altogether a

foolish man. He did not leave his farm until he

had something else to do.

Of all the simpletons the stars shine on there

is none more foolish than a man who leaves one

job before he has obtained another. And that has

especial reference to gentlemen of my

profession, and has no reference to a man

seeking a divorce. So I say this old farmer did

not leave one job until he had obtained another.

He wrote to Canada, but his cousin replied that

he could not engage him because he did not know

anything about the oil business. "Well, then,"

said he, "I will understand it." So he set

himself at the study of the whole subject. He

began at the second day of the creation, he

studied the subject from the primitive

vegetation to the coal oil stage, until he knew

all about it. Then he wrote to his cousin and

said, "Now I understand the oil business." And

his cousin replied to him, "All right, then,

come on."

That man, by the record of the country, sold his

farm for eight hundred and thirty-three dollars

even money, "no cents." He had scarcely gone

from that farm before the man who purchased it

went out to arrange for watering the cattle and

he found that the previous owner had arranged

the matter very nicely. There is a stream

running down the hillside there, and the

previous owner had gone out and put a plank

across that stream at an angle, extending across

the brook and down edgewise a few inches under

the surface of the water. The purpose of the

plank across that brook was to throw over to the

other bank a dreadful-looking scum through which

the cattle would not put their noses to drink

above the plank, although they would drink the

water on one side below it.

Thus that man who had gone to Canada had been

himself damming back for twenty-three years a

flow of coal oil which the State Geologist of

Pennsylvania declared officially, as early as

1870, was then worth to our state a hundred

millions of dollars. The city of Titusville now

stands on that farm and those Pleasantville

wells flow on, and that farmer who had studied

all about the formation of oil since the second

day of God's creation clear down to the present

time, sold that farm for $833, no cents again

I say, "no sense."

But I need another illustration, and I found

that in Massachusetts, and I am sorry I did,

because that is my old state. This young man I

mention went out of the state to study went

down to Yale College and studied mines and

mining. They paid him fifteen dollars a week

during his last year for training students who

were behind their classes in mineralogy, out of

hours, of course, while pursuing his own

studies. But when he graduated they raised his

pay from fifteen dollars to forty-five dollars

and offered him a professorship. Then he went

straight home to his mother and said, "Mother, I

won't work for forty-five dollars a week. What

is forty-five dollars a week for a man with a

brain like mine! Mother, let's go out to

California and stake out gold claims and be

immensely rich." "Now," said his mother, "it is

just as well to be happy as it is to be rich."

But as he was the only son he had his way they

always do; and they sold out in Massachusetts

and went to Wisconsin, where he went into the

employ of the Superior Copper Mining Company,

and he was lost from sight in the employ of that

company at fifteen dollars a week again. He was

also to have an interest in any mines that he

should discover for that company. But I do not

believe that he has ever discovered a mine I

do not know anything about it, but I do not

believe he has. I know he had scarcely gone from

the old homestead before the farmer who had

bought the homestead went out to dig potatoes,

and he was bringing them in a large basket

through the front gateway, the ends of the stone

wall came so near together at the gate that the

basket hugged very tight. So he set the basket

on the ground and pulled, first on one side and

then on the other side.

Our farms in Massachusetts are mostly stone

walls, and the farmers have to be economical

with their gateways in order to have some place

to put the stones. That basket hugged so tight

there that as he was hauling it through he

noticed in the upper stone next the gate a block

of native silver, eight inches square; and this

professor of mines and mining and mineralogy,

who would not work for forty-five dollars a

week, when he sold that homestead in

Massachusetts, sat right on that stone to make

the bargain. He was brought up there; he had

gone back and forth by that piece of silver,

rubbed it with his sleeve, and it seemed to say,

"Come now, now, now, here is a hundred thousand

dollars. Why not take me? " But he would not

take it. There was no silver in Newburyport; it

was all away off well, I don't know where; he

didn't, but somewhere else and he was a

professor of mineralogy.

I do not know of anything I would enjoy better

than to take the whole time tonight telling of

blunders like that I have heard professors make.

Yet I wish I knew what that man is doing out

there in Wisconsin. I can imagine him out there,

as he sits by his fireside, and he is saying to

his friends. "Do you know that man Conwell that

lives in Philadelphia?" "Oh, yes, I have heard

of him." "And do you know that man Jones that

lives in that city?" "Yes, I have heard of him."

And then he begins to laugh and laugh and says

to his friends, "They have done the same thing I

did, precisely." And that spoils the whole joke,

because you and I have done it.

Ninety out of every hundred people here have

made that mistake this very day. I say you ought

to be rich; you have no right to be poor. To

live in Philadelphia and not be rich is a

misfortune, and it is doubly a misfortune,

because you could have been rich just as well as

be poor. Philadelphia furnishes so many

opportunities. You ought to be rich. But persons

with certain religious prejudice will ask, "How

can you spend your time advising the rising

generation to give their time to getting money

dollars and cents the commercial spirit?"

Yet I must say that you ought to spend time

getting rich. You and I know there are some

things more valuable than money; of course, we

do. Ah, yes! By a heart made unspeakably sad by

a grave on which the autumn leaves now fall, I

know there are some things higher and grander

and sublimer than money. Well does the man know,

who has suffered, that there are some things

sweeter and holier and more sacred than gold.

Nevertheless, the man of common sense also knows

that there is not any one of those things that

is not greatly enhanced by the use of money.

Money is power.

Love is the grandest thing on God's earth, but

fortunate the lover who has plenty of money.

Money is power: money has powers; and for a man

to say, "I do not want money," is to say, "I do

not wish to do any good to my fellowmen." It is

absurd thus to talk. It is absurd to disconnect

them. This is a wonderfully great life, and you

ought to spend your time getting money, because

of the power there is in money. And yet this

religious prejudice is so great that some people

think it is a great honor to be one of God's

poor. I am looking in the faces of people who

think just that way.

I heard a man once say in a prayer-meeting that

he was thankful that he was one of God's poor,

and then I silently wondered what his wife would

say to that speech, as she took in washing to

support the man while he sat and smoked on the

veranda. I don't want to see any more of that

kind of God's poor. Now, when a man could have

been rich just as well, and he is now weak

because he is poor, he has done some great

wrong; he has been untruthful to himself; he has

been unkind to his fellowmen. We ought to get

rich if we can by honorable and Christian

methods, and these are the only methods that

sweep us quickly toward the goal of riches.

I remember, not many years ago, a young

theological student who came into my office and

said to me that he thought it was his duty to

come in and "labor with me." I asked him what

had happened, and he said: "I feel it is my duty

to come in and speak to you, sir, and say that

the Holy Scriptures declare that money is the

root of all evil." I asked him where he found

that saying, and he said he found it in the

Bible. I asked him whether he had made a new

Bible, and he said, no, he had not gotten a new

Bible, that it was in the old Bible. "Well," I

said, "if it is in my Bible, I never saw it.

Will you please get the textbook and let me see

it?"

He left the room and soon came stalking in with

his Bible open, with all the bigoted pride of

the narrow sectarian, who founds his creed on

some misinterpretation of Scripture, and he puts

the Bible down on the table before me and fairly

squealed into my ear, "There it is. You can read

it for yourself." I said to him, "Young man, you

will learn, when you get a little older, that

you cannot trust another denomination to read

the Bible for you." I said, "Now, you belong to

another denomination. Please read it to me, and

remember that you are taught in a school where

emphasis is exegesis." So he took the Bible and

read it: "The love of money is the root of all

evil." Then he had it right.

The Great Book has come back into the esteem and

love of the people, and into the respect of the

greatest minds of earth, and now you can quote

it and rest your life and your death on it

without more fear. So, when he quoted right from

the Scriptures he quoted the truth. "The love of

money is the root of all evil." Oh, that is it.

It is the worship of the means instead of the

end. Though you cannot reach the end without the

means. When a man makes an idol of the money

instead of the purposes for which it may be

used, when he squeezes the dollar until the

eagle squeals, then it is made the root of all

evil. Think, if you only had the money, what you

could do for your wife, your child, and for your

home and your city. Think how soon you could

endow the Temple College yonder if you only had

the money and the disposition to give it; and

yet, my friend, people say you and I should not

spend the time getting rich. How inconsistent

the whole thing is. We ought to be rich, because

money has power.

I think the best thing for me to do is to

illustrate this, for if I say you ought to get

rich, I ought, at least, to suggest how it is

done. We get a prejudice against rich men

because of the lies that are told about them.

The lies that are told about Mr. Rockefeller

because he has two hundred million dollars so

many believe them; yet how false is the

representation of that man to the world. How

little we can tell what is true nowadays when

newspapers try to sell their papers entirely on

some sensation! The way they lie about the rich

men is something terrible, and I do not know

that there is anything to illustrate this better

than what the newspapers now say about the city

of Philadelphia.

A young man came to me the other day and said,

"If Mr. Rockefeller, as you think, is a good

man, why is it that everybody says so much

against him?" It is because he has gotten ahead

of us; that is the whole of it just gotten

ahead of us. Why is it Mr. Carnegie is

criticized so sharply by an envious world!

Because he has gotten more than we have. If a

man knows more than I know, don't I incline to

criticize somewhat his learning? Let a man stand

in a pulpit and preach to thousands, and if I

have fifteen people in my church, and they're

all asleep, don't I criticize him? We always do

that to the man who gets ahead of us. Why, the

man you are criticizing has one hundred

millions, and you have fifty cents, and both of

you have just what you are worth.

One of the richest men in this country came into

my home and sat down in my parlor and said: "Did

you see all those lies about my family in the

papers?" "Certainly I did; I knew they were lies

when I saw them." "Why do they lie about me the

way they do?" "Well," I said to him, "if you

will give me your check for one hundred

millions, I will take all the lies along with

it." "Well," said he, "I don't see any sense in

their thus talking about my family and myself.

Conwell, tell me frankly, what do you think the

American people think of me?" "Well," said I,

"they think you are the blackest hearted villain

that ever trod the soil!" "But what can I do

about it?" There is nothing he can do about it,

and yet he is one of the sweetest Christian men

I ever knew. If you get a hundred millions you

will have the lies; you will be lied about, and

you can judge your success in any line by the

lies that are told about you. I say that you

ought to be rich.

But there are ever coming to me young men who

say, "I would like to go into business, but I

cannot." "Why not?" "Because I have no capital

to begin on." Capital, capital to begin on!

What! young man! Living in Philadelphia and

looking at this wealthy generation, all of whom

began as poor boys, and you want capital to

begin on? It is fortunate for you that you have

no capital. I am glad you have no money. I pity

a rich man's son. A rich man's son in these days

of ours occupies a very difficult position. They

are to be pitied. A rich man's son cannot know

the very best things in human life. He cannot.

The statistics of Massachusetts show us that not

one out of seventeen rich men's sons ever die

rich. They are raised in luxury, they die in

poverty. Even if a rich man's son retains his

father's money, even then he cannot know the

best things of life.

A young man in our college yonder asked me to

formulate for him what I thought was the

happiest hour in a man's history, and I studied

it long and came back convinced that the

happiest hour that any man ever sees in any

earthly matter is when a young man takes his

bride over the threshold of the door, for the

first time, of the house he himself has earned

and built, when he turns to his bride and with

an eloquence greater than any language of mine,

he sayeth to his wife, "My loved one, I earned

this home myself; I earned it all. It is all

mine, and I divide it with thee." That is the

grandest moment a human heart may ever see. But

a rich man's son cannot know that. He goes into

a finer mansion, it may be, but he is obliged to

go through the house and say, "Mother gave me

this, mother gave me that, my mother gave me

that, my mother gave me that," until his wife

wishes she had married his mother.

Oh, I pity a rich man's son. I do. Until he gets

so far along in his dudeism that he gets his

arms up like that and can't get them down.

Didn't you ever see any of them astray at

Atlantic City? I saw one of these scarecrows

once and I never tire thinking about it. I was

at Niagara Falls lecturing, and after the

lecture I went to the hotel, and when I went up

to the desk there stood there a millionaire's

son from New York. He was an indescribable

specimen of anthropologic potency. He carried a

goldheaded cane under his arm more in its head

than he had in his. I do not believe I could

describe the young man if I should try. But

still I must say that he wore an eye-glass he

could not see through; patent leather shoes he

could not walk in, and pants he could not sit

down in dressed like a grasshopper!

Well, this human cricket came up to the clerk's

desk just as I came in. He adjusted his unseeing

eye-glass in this wise and lisped to the clerk,

because it's "Hinglish, you know," to lisp: "Thir,

thir, will you have the kindness to fuhnish me

with thome papah and thome envelopehs!" The

clerk measured that man quick, and he pulled out

a drawer and took some envelopes and paper and

cast them across the counter and turned away to

his books.

You should have seen that specimen of humanity

when the paper and envelopes came across the

counter he whose wants had always been

anticipated by servants. He adjusted his

unseeing eye-glass and he yelled after that

clerk: "Come back here, thir, come right back

here. Now, thir, will you order a thervant to

take that papah and thothe envelopehs and carry

them to yondah dethk." Oh, the poor, miserable,

contemptible American monkey! He couldn't carry

paper and envelopes twenty feet. I suppose he

could not get his arms down. I have no pity for

such travesties of human nature. If you have no

capital, I am glad of it. You don't need

capital; you need common sense, not copper

cents.

A. T. Stewart, the great princely merchant of

New York, the richest man in America in his

time, was a poor boy; he had a dollar and a half

and went into the mercantile business. But he

lost eighty-seven and a half cents of his first

dollar and a half because he bought some needles

and thread and buttons to sell, which people

didn't want.

Are you poor? It is because you are not wanted

and are left on your own hands. There was the

great lesson. Apply it whichever way you will it

comes to every single person's life, young or

old. He did not know what people needed, and

consequently bought something they didn't want,

and had the goods left on his hands a dead loss.

A. T. Stewart learned there the great lesson of

his mercantile life and said "I will never buy

anything more until I first learn what the

people want; then I'll make the purchase." He

went around to the doors and asked them what

they did want, and when he found out what they

wanted, he invested his sixty-two and a half

cents and began to supply a "known demand." I

care not what your profession or occupation in

life may be; I care not whether you are a

lawyer, a doctor, a housekeeper, teacher or

whatever else, the principle is precisely the

same. We must know what the world needs first

and then invest ourselves to supply that need,

and success is almost certain.

A. T. Stewart went on until he was worth forty

millions. "Well," you will say, "a man can do

that in New York, but cannot do it here in

Philadelphia." The statistics very carefully

gathered in New York in 1889 showed one hundred

and seven millionaires in the city worth over

ten millions apiece. It was remarkable and

people think they must go there to get rich. Out

of that one hundred and seven millionaires only

seven of them made their money in New York, and

the others moved to New York after their

fortunes were made, and sixty- seven out of the

remaining hundred made their fortunes in towns

of less than six thousand people, and the

richest man in the country at that time lived in

a town of thirty-five hundred inhabitants, and

always lived there and never moved away. It is

not so much where you are as what you are. But

at the same time if the largeness of the city

comes into the problem, then remember it is the

smaller city that furnishes the great

opportunity to make the millions of money.

The best illustration that I can give is in

reference to John Jacob Astor, who was a poor

boy and who made all the money of the Astor

family. He made more than his successors have

ever earned, and yet he once held a mortgage on

a millinery store in New York, and because the

people could not make enough money to pay the

interest and the rent, he foreclosed the

mortgage and took possession of the store and

went into partnership with the man who had

failed. He kept the same stock, did not give

them a dollar of capital, and he left them alone

and he went out and sat down upon a bench in the

park.

Out there on that bench in the park he had the

most important, and, to my mind, the pleasantest

part of that partnership business. He was

watching the ladies as they went by; and where

is the man that wouldn't get rich at that

business? But when John Jacob Astor saw a lady

pass, with her shoulders back and her head up,

as if she did not care if the whole world looked

on her, he studied her bonnet; and before that

bonnet was out of sight he knew the shape of the

frame and the color of the trimmings, the curl

of the something on a bonnet. Sometimes I try

to describe a woman's bonnet, but it is of

little use, for it would be out of style

tomorrow night.

So John Jacob Astor went to the store and said:

"Now, put in the show window just such a bonnet

as I describe to you because," said he, "I have

just seen a lady who likes just such a bonnet.

Do not make up any more till I come back." And

he went out again and sat on that bench in the

park, and another lady of a different form and

complexion passed him with a bonnet of different

shape and color, of course. "Now," said he, "put

such a bonnet as that in the show window."

He didn't fill his show window with hats and

bonnets which drive people away and then sit in

the back of the store and bawl because the

people go somewhere else to trade. He didn't put

a hat or bonnet in that show window the like of

which he had not seen before it was made up.

In our city especially, there are great

opportunities for manufacturing, and the time

has come when the line is drawn very sharply

between the stockholders of the factory and

their employees. Now, friends, there has also

come a discouraging gloom upon this country and

the laboring men are beginning to feel that they

are being held down by a crust over their heads

through which they find it impossible to break,

and the aristocratic money owner himself is so

far above that he will never descend to their

assistance. That is the thought that is in the

minds of our people. But, friends, never in the

history of our country was there an opportunity

so great for the poor man to get rich as there

is now and in the city of Philadelphia. The very

fact that they get discouraged is what prevents

them from getting rich. That is all there is to

it. The road is open, and let us keep it open

between the poor and the rich.

I know that the labor unions have two great

problems to contend with, and there is only one

way to solve them. The labor unions are doing as

much to prevent its solving as are capitalists

today, and there are positively two sides to it.

The labor union has two difficulties; the first

one is that it began to make a labor scale for

all classes on a par, and they scale down a man

that can earn five dollars a day to two and a

half a day, in order to level up to him an

imbecile that cannot earn fifty cents a day.

That is one of the most dangerous and

discouraging things for the working man. He

cannot get the results of his work if he do

better work or higher work or work longer; that

is a dangerous thing, and in order to get every

laboring man free and every American equal to

every other American, let the laboring man ask

what he is worth and get it not let any

capitalist say to him: "You shall work for me

for half of what you are worth"; nor let any

labor organization say: "You shall work for the

capitalist for half your worth."

Be a man, be independent, and then shall the

laboring man find the road ever open from

poverty to wealth.

The other difficulty that the labor union has to

consider, and this problem they have to solve

themselves, is the kind of orators who come and

talk to them about the oppressive rich. I can in

my dreams recite the oration I have heard again

and again under such circumstances. My life has

been with the laboring man. I am a laboring man

myself. I have often, in their assemblies, heard

the speech of the man who has been invited to

address the labor union. The man gets up before

the assembled company of honest laboring men and

he begins by saying: "Oh, ye honest, industrious

laboring men, who have furnished all the capital

of the world, who have built all the palaces and

constructed all the railroads and covered the

ocean with her steamships. Oh, you laboring men!

You are nothing but slaves; you are ground down

in the dust by the capitalist who is gloating

over you as he enjoys his beautiful estates and

as he has his banks filled with gold, and every

dollar he owns is coined out of the heart's

blood of the honest laboring man." Now, that is

a lie, and you know it is a lie; and yet that is

the kind of speech that they are hearing all the

time, representing the capitalists as wicked and

the laboring man so enslaved.

Why, how wrong it is! Let the man who loves his

flag and believes in American principles

endeavor with all his soul to bring the

capitalists and the laboring man together until

they stand side by side, and arm in arm, and

work for the common good of humanity.

He is an enemy to his country who sets capital

against labor or labor against capital.

Suppose I were to go down through this audience

and ask you to introduce me to the great

inventors who live here in Philadelphia. "The

inventors of Philadelphia," you would say, "why,

we don't have any in Philadelphia. It is too

slow to invent anything." But you do have just

as great inventors, and they are here in this

audience, as ever invented a machine. But the

probability is that the greatest inventor to

benefit the world with his discovery is some

person, perhaps some lady, who thinks she could

not invent anything.

Did you ever study the history of invention and

see how strange it was that the man who made the

greatest discovery did it without any previous

idea that he was an inventor? Who are the great

inventors? They are persons with plain,

straightforward common sense, who saw a need in

the world and immediately applied themselves to

supply that need. If you want to invent

anything, don't try to find it in the wheels in

your head nor the wheels in your machine, but

first find out what the people need, and then

apply yourself to that need, and this leads to

invention on the part of people you would not

dream of before. The great inventors are simply

great men; the greater the man the more simple

the man; and the more simple a machine, the more

valuable it is.

Did you ever know a really great man? His ways

are so simple, so common, so plain, that you

think any one could do what he is doing. So it

is with the great men the world over. If you

know a really great man, a neighbor of yours,

you can go right up to him and say, "How are

you, Jim, good morning, Sam." Of course you can,

for they are always so simple.

When I wrote the life of General Garfield, one

of his neighbors took me to his back door, and

shouted, "Jim, Jim, Jim!" and very soon "Jim"

came to the door and General Garfield let me in

one of the grandest men of our century. The

great men of the world are ever so. I was down

in Virginia and went up to an educational

institution and was directed to a man who was

setting out a tree. I approached him and said,

"Do you think it would be possible for me to see

General Robert E. Lee, the President of the

University?" He said, "Sir, I am General Lee."

Of course, when you meet such a man, so noble a

man as that, you will find him a simple, plain

man. Greatness is always just so modest and

great inventions are simple.

I asked a class in school once who were the

great inventors, and a little girl popped up and

said, "Columbus." Well, now, she was not so far

wrong. Columbus bought a farm and he carried on

that farm just as I carried on my father's farm.

He took a hoe and went out and sat down on a

rock. But Columbus, as he sat upon that shore

and looked out upon the ocean, noticed that the

ships, as they sailed away, sank deeper into the

sea the farther they went. And since that time

some other "Spanish ships" have sunk into the

sea. But as Columbus noticed that the tops of

the masts dropped down out of sight, he said:

"That is the way it is with this hoe handle; if

you go around this hoe handle, the farther off

you go the farther down you go. I can sail

around to the East Indies." How plain it all

was. How simple the mind majestic like the

simplicity of a mountain in its greatness. Who

are the great inventors? They are ever the

simple, plain, everyday people who see the need

and set about to supply it.

I was once lecturing in North Carolina, and the

cashier of the bank sat directly behind a lady

who wore a very large hat. I said to that

audience, "Your wealth is too near to you; you

are looking right over it." He whispered to his

friend, "Well, then, my wealth is in that hat."

A little later, as he wrote me, I said,

"Wherever there is a human need there is a

greater fortune than a mine can furnish." He

caught my thought, and he drew up his plan for a

better hat pin than was in the hat before him

and the pin is now being manufactured. He was

offered fifty-two thousand dollars for his

patent. That man made his fortune before he got

out of that hall. This is the whole question: Do

you see a need?"

I remember well a man up in my native hills, a

poor man, who for twenty years was helped by the

town in his poverty, who owned a widespreading

maple tree that covered the poor man's cottage

like a benediction from on high. I remember that

tree, for in the spring there were some

roguish boys around that neighborhood when I was

young in the spring of the year the man would

put a bucket there and the spouts to catch the

maple sap, and I remember where that bucket was;

and when I was young the boys were, oh, so mean,

that they went to that tree before that man had

gotten out of bed in the morning, and after he

had gone to bed at night, and drank up that

sweet sap, I could swear they did it.

He didn't make a great deal of maple sugar from

that tree. But one day he made the sugar so

white and crystalline that the visitor did not

believe it was maple sugar; thought maple sugar

must be red or black. He said to the old man:

"Why don't you make it that way and sell it for

confectionery?" The old man caught his thought

and invented the "rock maple crystal," and

before that patent expired he had ninety

thousand dollars and had built a beautiful

palace on the site of that tree. After forty

years owning that tree he awoke to find it had

fortunes of money indeed in it. And many of us

are right by the tree that has a fortune for us,

and we own it, possess it, do what we will with

it, but we do not learn its value because we do

not see the human need, and in these discoveries

and inventions that is one of the most romantic

things of life. I have received letters from all

over the country and from England, where I have

lectured, saying that they have discovered this

and that, and one man out in Ohio took me

through his great factories last spring, and

said that they cost him $680,000, and, said he,

"I was not worth a cent in the world when I

heard your lecture 'Acres of Diamonds'; but I

made up my mind to stop right here and make my

fortune here, and here it is." He showed me

through his unmortgaged possessions. And this is

a continual experience now as I travel through

the country, after these many years. I mention

this incident, not to boast, but to show you

that you can do the same if you will.

Who are the great inventors? I remember a good

illustration in a man who used to live in East

Brookfield, Mass. He was a shoemaker, and he was

out of work and he sat around the house until

his wife told him "to go out doors." And he did

what every husband is compelled by law to do

he obeyed his wife. And he went out and sat down

on an ash barrel in his back yard. Think of it!

Stranded on an ash barrel and the enemy in

possession of the house! As he sat on that ash

barrel, he looked down into that little brook

which ran through that back yard into the

meadows, and he saw a little trout go flashing

up the stream and hiding under the bank. I do

not suppose he thought of Tennyson's beautiful

poem:

"Chatter, chatter as I flow,

To join the brimming river,

Men may come, and men

may go, But I go on forever."

But as this man looked into the brook, he leaped

off that ash barrel and managed to catch the

trout with his fingers, and sent it to

Worcester. They wrote back that they would give

a five dollar bill for another such trout as

that, not that it was worth that much, but they

wished to help the poor man. So this shoemaker

and his wife, now perfectly united, that

five-dollar bill in prospect, went out to get

another trout. They went up the stream to its

source and down to the brimming river, but not

another trout could they find in the whole

stream; and so they came home disconsolate and

went to the minister. The minister didn't know

how trout grew, but he pointed the way. Said he,

"Get Seth Green's book, and that will give you

the information you want."

They did so, and found all about the culture of

trout. They found that a trout lays thirty-six

hundred eggs every year and every trout gains a

quarter of a pound every year, so that in four

years a little trout will furnish four tons per

annum to sell to the market at fifty cents a

pound. When they found that, they said they

didn't believe any such story as that, but if

they could get five dollars apiece they could

make something. And right in that same back yard

with the coal sifter up stream and window screen

down the stream, they began the culture of

trout. They afterwards moved to the Hudson, and

since then he has become the authority in the

United States upon the raising of fish, and he

has been next to the highest on the United

States Fish Commission in Washington. My lesson

is that man's wealth was out here in his back

yard for twenty years, but he didn't see it

until his wife drove him out with a mop stick.

I remember meeting personally a poor carpenter

of Hingham, Massachusetts, who was out of work

and in poverty. His wife also drove him out of

doors. He sat down on the shore and whittled a

soaked shingle into a wooden chain. His children

quarreled over it in the evening, and while he

was whittling a second one, a neighbor came

along and said, "Why don't you whittle toys if

you can carve like that?" He said, "I don't know

what to make!"

There is the whole thing. His neighbor said to

him: "Why don't you ask your own children?" Said

he, "What is the use of doing that? My children

are different from other people's children." I

used to see people like that when I taught

school. The next morning when his boy came down

the stairway, he said, "Sam, what do you want

for a toy?" "I want a wheelbarrow." When his

little girl came down, he asked her what she

wanted, and she said, "I want a little doll's

wash-stand, a little doll's carriage, a little

doll's umbrella," and went on with a whole lot

of things that would have taken his lifetime to

supply. He consulted his own children right

there in his own house and began to whittle out

toys to please them.

He began with his jack-knife, and made those

unpainted Hingham toys. He is the richest man in

the entire New England States, if Mr. Lawson is

to be trusted in his statement concerning such

things, and yet that man's fortune was made by

consulting his own children in his own house.

You don't need to go out of your own house to

find out what to invent or what to make. I

always talk too long on this subject. I would

like to meet the great men who are here tonight.

The great men! We don't have any great men in

Philadelphia. Great men! You say that they all

come from London, or San Francisco, or Rome, or

Manayunk, or anywhere else but there anywhere

else but Philadelphia and yet, in fact, there

are just as great men in Philadelphia as in any

city of its size. There are great men and women

in this audience.

Great men, I have said, are very simple men.

Just as many great men here as are to be found

anywhere. The greatest error in judging great

men is that we think that they always hold an

office. The world knows nothing of its greatest

men. Who are the great men of the world? The

young man and young woman may well ask the

question. It is not necessary that they should

hold an office, and yet that is the popular

idea. That is the idea we teach now in our high

schools and common schools, that the great men

of the world are those who hold some high

office, and unless we change that very soon and

do away with that prejudice, we are going to

change to an empire. There is no question about

it. We must teach that men are great only on

their intrinsic value, and not on the position

they may incidentally happen to occupy. And yet,

don't blame the young men saying that they are

going to be great when they get into some

official position.

I ask this audience again who of you are going

to be great? Says a young man: "I am going to be

great." "When are you going to be great?" "When

I am elected to some political office." Won't

you learn the lesson, young man; that it is

prima facie evidence of littleness to hold

public office under our form of government?

Think of it. This is a government of the people,

and by the people, and for the people, and not

for the officeholder, and if the people in this

country rule as they always should rule, an

officeholder is only the servant of the people,

and the Bible says that "the servant cannot be

greater than his master."

The Bible says that "he that is sent cannot be

greater than he who sent him." In this country

the people are the masters, and the

officeholders can never be greater than the

people; they should be honest servants of the

people, but they are not our greatest men. Young

man, remember that you never heard of a great

man holding any political office in this country

unless he took that office at an expense to

himself. It is a loss to every great man to take

a public office in our country. Bear this in

mind, young man, that you cannot be made great

by a political election.

Another young man says, "I am going to be a

great man in Philadelphia some time." "Is that

so? When are you going to be great?" "When there

comes another war! When we get into difficulty

with Mexico, or England, or Russia, or Japan, or

with Spain again over Cuba, or with New Jersey,

I will march up to the cannon's mouth, and amid

the glistening bayonets I will tear down their

flag from its staff, and I will come home with

stars on my shoulders, and hold every office in

the gift of the government, and I will be

great." "No, you won't! No, you won't; that is

no evidence of true greatness, young man." But

don't blame that young man for thinking that

way; that is the way he is taught in the high

school. That is the way history is taught in

college. He is taught that the men who held the

office did all the fighting.

I remember we had a Peace Jubilee here in

Philadelphia soon after the Spanish War. Perhaps

some of these visitors think we should not have

had it until now in Philadelphia, and as the

great procession was going up Broad Street I was

told that the tally-ho coach stopped right in

front of my house, and on the coach was Hobson,

and all the people threw up their hats and swung

their handkerchiefs, and shouted "Hurrah for

Hobson!" I would have yelled too, because he

deserves much more of his country that he has

ever received. But suppose I go into the high

school tomorrow and ask, "Boys, who sunk the

Merrimac?" If they answer me "Hobson," they tell

me seven-eighths of a lie seven- eighths of a

lie, because there were eight men who sunk the

Merrimac. The other seven men, by virtue of

their position, were continually exposed to the

Spanish fire while Hobson, as an officer, might

reasonably be behind the smoke-stack.

Why, my friends, in this intelligent audience

gathered here tonight I do not believe I could

find a single person that can name the other

seven men who were with Hobson. Why do we teach

history in that way? We ought to teach that

however humble the station a man may occupy, if

he does his full duty in his place, he is just

as much entitled to the American people's honor

as is a king upon a throne. We do teach it as a

mother did her little boy in New York when he

said, "Mamma, what great building is that?"

"That is General Grant's tomb." "Who was General

Grant?" "He was the man who put down the

rebellion." Is that the way to teach history?

Do you think we would have gained a victory if

it had depended on General Grant alone. Oh, no.

Then why is there a tomb on the Hudson at all?

Why, not simply because General Grant was

personally a great man himself, but that tomb is

there because he was a representative man and

represented two hundred thousand men who went

down to death for this nation and many of them

as great as General Grant. That is why that

beautiful tomb stands on the heights over the

Hudson.

I remember an incident that will illustrate

this, the only one that I can give tonight. I am

ashamed of it, but I don't dare leave it out. I

close my eyes now; I look back through the years

to 1863; I can see my native town in the

Berkshire Hills, I can see that cattle-show

ground filled with people; I can see the church

there and the town hall crowded, and hear bands

playing, and see flags flying and handkerchiefs

streaming well do I recall at this moment that

day.

The people had turned out to receive a company

of soldiers, and that company came marching up

on the Common. They had served out one term in

the Civil War and had reenlisted, and they were

being received by their native townsmen. I was

but a boy, but I was captain of that company,

puffed out with pride on that day why, a

cambric needle would have burst me all to

pieces.

As I marched on the Common at the head of my

company, there was not a man more proud than I.

We marched into the town hall and then they

seated my soldiers down in the center of the

house and I took my place down on the front

seat, and then the town officers filed through

the great throng of people, who stood close and

packed in that little hall. They came up on the

platform, formed a half circle around it, and

the mayor of the town, the "chairman of the

selectmen" in New England, took his seat in the

middle of that half circle.

He was an old man, his hair was gray; he never

held an office before in his life. He thought

that an office was all he needed to be a truly

great man, and when he came up he adjusted his

powerful spectacles and glanced calmly around

the audience with amazing dignity. Suddenly his

eyes fell upon me, and then the good old man

came right forward and invited me to come up on

the stand with the town officers. Invited me up

on the stand! No town officer ever took notice

of me before I went to war. Now, I should not

say that. One town officer was there who advised

the teachers to "whale" me, but I mean no

"honorable mention."

So I was invited up on the stand with the town

officers. I took my seat and let my sword fall

on the floor, and folded my arms across my

breast and waited to be received. Napoleon the

Fifth! Pride goeth before destruction and a

fall. When I had gotten my seat and all became

silent through the hall, the chairman of the

selectmen arose and came forward with great

dignity to the table, and we all supposed he

would introduce the Congregational minister, who

was the only orator in the town, and who would

give the oration to the returning soldiers.

But, friends, you should have seen the surprise

that ran over that audience when they discovered

that this old farmer was going to deliver that

oration himself. He had never made a speech in

his life before, but he fell into the same error

that others have fallen into, he seemed to think

that the office would make him an orator. So he

had written out a speech and walked up and down

the pasture until he had learned it by heart and

frightened the cattle, and he brought that

manuscript with him, and, taking it from his

pocket, he spread it carefully upon the table.

Then he adjusted his spectacles to be sure that

he might see it, and walked far back on the

platform and then stepped forward like this. He

must have studied the subject much, for he

assumed an elocutionary attitude; he rested

heavily upon his left heel, slightly advanced

the right foot, threw back his shoulders, opened

the organs of speech, and advanced his right

hand at an angle of forty-five.

As he stood in this elocutionary attitude this

is just the way that speech went, this is it

precisely. Some of my friends have asked me if I

do not exaggerate it, but I could not exaggerate

it. Impossible! This is the way it went;

although I am not here for the story but the

lesson that is back of it:

"Fellow citizens" As soon as he heard his

voice, his hand began to shake like that, his

knees began to tremble, and then he shook all

over. He coughed and choked and finally came

around to look at his manuscript. Then he began

again: "Fellow citizens, we are we are we

are we are we are very happy we are very

happy we are very happy to welcome back to

their native town these soldiers who have fought

and bled and come back again to their native

town. We are especially we are especially we

are especially we are especially pleased to

see with us today this young hero" (that meant me)

"this young hero who in imagination" (friends,

remember, he said that; if he had

not said "in imagination" I would not be egotistical enough

to refer to it) "this young hero who, in

imagination, we have seen leading his troops

leading we have seen leading we have seen

leading his troops on to the deadly breach. We

have seen his shining his shining we have

seen his shining we have seen his shining

his shining sword flashing in the sunlight as

he shouted to his troops, 'Come on!'"

Oh dear, dear, dear, dear! How little that good,

old man knew about war. If he had known anything

about war, he ought to have known what any

soldier in this audience knows is true, that it

is next to a crime for an officer of infantry

ever in time of danger to go ahead of his men.

I, with my shining sword flashing in the

sunlight, shouting to my troops: "Come on." I

never did it. Do you suppose I would go ahead of

my men to be shot in the front by the enemy and

in the back by my own men? That is no place for

an officer. The place for the officer is behind

the private soldier in actual fighting.

How often, as a staff officer, I rode down the

line when the rebel cry and yell was coming out

of the woods, sweeping along over the fields,

and shouted, "Officers to the rear! Officers to

the rear!" and then every officer goes behind

the line of battle, and the higher the officer

rank, the farther behind he goes. Not because he

is any the less brave, but because the laws of

war require that to be done. If the general came

up on the front line and were killed you would

lose your battle anyhow, because he has the plan

of the battle in his brain, and must be kept in

comparative safety.

I, with my "shining sword flashing in the

sunlight." Ah! There sat in the hall that day

men who had given that boy their last hardtack,

who had carried him on their backs through deep

rivers. But some were not there; they had gone

down to death for their country. The speaker

mentioned them, but they were but little

noticed, and yet they had gone down to death for

their country, gone down for a cause they

believed was right and still believe was right,

though I grant to the other side the same that I

ask for myself. Yet these men who had actually

died for their country were little noticed, and

the hero of the hour was this boy.

Why was he the hero? Simply because that man

fell into the same foolishness. This boy was an

officer, and those were only private soldiers. I

learned a lesson that I will never forget.

Greatness consists not in holding some office;

greatness really consists in doing some great

deed with little means, in the accomplishment of

vast purposes from the private ranks of life,

that is true greatness.

He who can give to this people better streets,

better homes, better schools, better churches,

more religion, more of happiness, more of God,

he that can be a blessing to the community in

which he lives tonight will be great anywhere,

but he who cannot be a blessing where he now

lives will never be great anywhere on the face

of God's earth. "We live in deeds, not years, in

feeling, not in figures on a dial; in thoughts,

not breaths; we should count time by heart

throbs, in the cause of right." Bailey says: "He

most lives who thinks most."

If you forget everything I have said to you, do

not forget this, because it contains more in two

lines than all I have said. Baily says: "He most

lives who thinks most, who feels the noblest,

and who acts the best."

More History

|

|