|

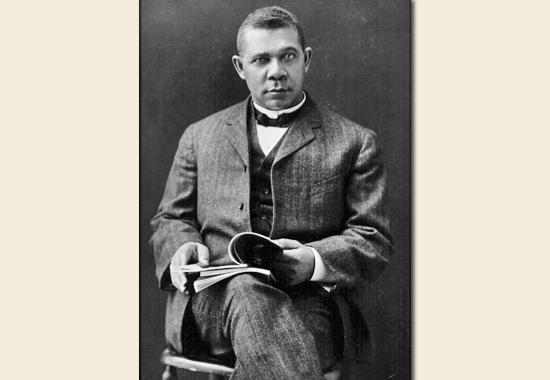

EDUCATION AS A MEANS RATHER THAN AN

END - B.T.

WASHINGTON 1896

Democracy and Education

It follows the full text transcript of

Booker T. Washington's Democracy and

Education

speech, delivered at Brooklyn, New York — September 30, 1896.

|

Mr. Chairman,

Ladies and

Gentlemen: |

It is said that

the strongest chain is no stronger than its

weakest link. In the Southern part of our

country there are 22 millions of your

brethren who are bound to you by ties which you

cannot tear asunder if you would. The most

intelligent man in your community has his

intelligence darkened by the ignorance of a

fellow citizen in the Mississippi bottoms. The

most wealthy in your city would be more wealthy

but for the poverty of a fellow being in the

Carolina rice swamps. The most moral and

religious among you has his religion and

morality modified by the degradation of the man

in the South whose religion is a mere matter of

form or emotionalism.

The vote in your state that is cast for the

highest and purest form of government is largely

neutralized by the vote of the man in Louisiana

whose ballot is stolen or cast in ignorance.

When the South is poor, you are poor; when the

South commits crime, you commit crime. My

friends, there is no mistake; you must help us

to raise the character of our civilization or

yours will be lowered.

No member of your

race in any part of our country can harm the

weakest and meanest member of mine without the

proudest and bluest blood in the city of

Brooklyn being degraded. The central ideal which

I wish you to help me consider is the reaching

and lifting up of the lowest, most unfortunate,

negative element that occupies so large a

proportion of our territory and composes so

large a percentage of our population. It seems

to me that there never was a time in the history

of our country when those interested in

education should more earnestly consider to what

extent the mere acquiring of a knowledge of

literature and science makes producers, lovers

of labor, independent, honest, unselfish, and,

above all, supremely good.

Call education by

what name you please, and if it fails to bring

about these results among the masses it falls

short of its highest end. The science, the art,

the literature that fails to reach down and

bring the humblest up to the fullest enjoyment

of the blessings of our government is weak, no

matter how costly the buildings or apparatus

used, or how modern the methods in instruction

employed.

The study of

arithmetic that does not result in making

someone more honest and self-reliant is

defective. The study of history that does not

result in making men conscientious in receiving

and counting the ballots of their fellow men is

most faulty. The study of art that does not

result in making the strong less willing to

oppress the weak means little. How I wish that

from the most humble log cabin schoolhouse in

Alabama we could burn it, as it were, into the

hearts and heads of all, that usefulness,

service to our brother, is the supreme end of

education. Putting the thought more directly as

it applies to conditions in the South:

Can you make your

intelligence affect us in the same ratio that

our ignorance affects you? Let us put a not

improbable case, one that involves peace or war,

the honor or dishonor of our nation — yea, the

very existence of the government. The North and

West are divided. There are five million votes

to be cast in the South, and of this number one

half are ignorant. Not only are one half the

voters ignorant, but, because of this ignorant

vote, corruption, dishonesty in a dozen forms

have crept into the exercise of the political

franchise, to the extent that the conscience of

the intelligent class is soured in its attempts

to defeat the will of the ignorant voters. Here,

then on the one hand you have an ignorant vote,

and on the other hand an intelligent vote minus

a conscience. The time may not be far off when

to this kind of jury we shall have to look for

the verdict that is to decide the course of our

democratic institutions.

When a great national calamity stares us in the

face, we are, I fear, too much given to

depending on a short campaign of education to do

on the hustings what should have been

accomplished in the schoolroom. With this

preliminary survey, let us examine with more

care the work to be done in the South before all

classes will be fit for the highest duties of

citizenship.

In reference to my own race I am confronted with

some embarrassment at the outset because of the

various and conflicting opinions as to what is

to be its final place in our economic and

political life. Within the last thirty

years — and, I might add, within the last three

months — it has been proven by eminent authority

that the Negro is increasing in numbers so fast

that it is only a question of a few years before

he will far outnumber the white race in the

South, and it has also been proven that the

Negro is fast dying out and it is only a

question of a few years before he will have

completely disappeared. It has also been proven

that crime among us is on the increase and that

crime is on the decrease; that education helps

the Negro, that education also hurts him; that

he is fast leaving the South and taking up his

residence in the North and West, and that the

tendency of the Negro is to drift to the

lowlands of the Mississippi bottoms. It has been

proven that as a slave laborer he produced less

cotton than a free man. It has been proven that

education unfits the Negro for work, and that

education also makes him more valuable as a

laborer; that he is our greatest criminal and

that he is our most law-abiding citizen.

In the midst of

these opinions, in the words of a modern

statesman, "I hardly know where I am at." I

hardly know whether I am myself or the other

fellow. But in the midst of this confusion there

are a few things of which I feel certain that

furnish a basis for thought and action. I know

that, whether in slavery or freedom, we have

always been loyal to the Stars and Stripes, that

no schoolhouse has been opened for us that has

not been filled; that 1,500,000 ballots that we

have the right to cast are as potent for weal

and woe as the ballot cast by the whitest and

most influential man in your commonwealth. I

know that wherever our life touches yours we

help or hinder; that wherever your life touches

ours you make us stronger or weaker. Further I

know that almost every other race that tried to

look the white man in the face has disappeared.

With all the conflicting opinions, and with the

full knowledge of all our weaknesses, I know

that only a few centuries ago this country we

went into slavery pagans: we came out

Christians; we went into slavery pieces of

property: we came out American citizens; we went

into slavery without a language: we came out

speaking the proud Anglo-Saxon tongue; we went

into slavery with the slave chains clanking

about our wrists: we came out with the American

ballot in our hands.

My friends, I

submit it to your sober and candid judgment, if

a race that is capable of such a test, such a

transformation, is not worth saving and making a

part, in reality as well as in name, of our

democratic government.

It is with an

ignorant race as it is with a child: it craves

at first the superficial, the ornamental, the

signs of progress rather than the reality. The

ignorant race is tempted to jump, at one bound,

to the position that it has required years of

hard struggle for others to reach. It seems to

me that the temptation in education and

missionary work is to do for a people a thousand

miles away without always making a careful study

of the needs and conditions of the people whom

we are trying to help. The temptation is to run

all people through a certain educational mold

regardless of the condition of the subject or

the end to be accomplished. Unfortunately for us

as a race, our education was begun, just after

the war, too nearly where New England education

ended. We seemed to overlook the fact that we

were dealing with a race that has little love

for labor in their native land and consequently

brought little love for labor with them to

America. Added to this was the fact that they

had been forced for two hundred and fifty years

to labor without compensation under

circumstances that were calculated to do

anything but teach them the dignity, beauty, and

civilizing power of intelligent labor. We forgot

the industrial education that was given the

Pilgrim Fathers of New England in clearing and

planting its cold, bleak, and snowy hills and

valleys, in providing shelter, founding the

small mills and factories, in supplying

themselves with home-made products, thus laying

the foundation of an industrial life that now

keeps going a large part of the colleges and

missionary effort of the world.

May I be tempted

one step further in showing how prone we are to

make our education formal, technical, instead of

making it meet the needs of conditions

regardless of formality and technicality?

At least eighty

per cent of my pupils in the South are found in

the rural districts, and they are dependent on

agriculture in some form for their support.

Notwithstanding in this instance we have a whole

race depending upon agriculture, and

notwithstanding thirty years have passed since

our freedom, aside from what we have done at

Hampton and Tuskegee and one or two other

institutions, not a thing has been attempted by

state or philanthropy in the way of educating

the race in this industry on which their very

existence depends.

Boys have been

taken from the farms and education in law,

theology, Hebrew, and Greek — educated in

everything else but the very subject they should

know the most about. I question whether or not

among all the educated colored people in the

United States you can find six, if we except the

institutions named, that have received anything

like a thorough training in agriculture. It

would have seemed, since self-support and

industrial independence are the first conditions

for lifting up any race, that education in

theoretical and practical agriculture,

horticulture, dairying, and stock-raising should

have occupied the first place in our system.

Some time ago when

we decided to make tailoring a part of our

training at the Tuskegee Institute, I was amazed

to find that it was almost impossible to find in

the whole country an educated colored man who

could teach the making of clothing. I could find

them by the score who could teach astronomy,

theology, Greek, or Latin, but almost none who

could instruct in the making of clothing,

something that has to be used by every one of us

every day in the year.

How often has my

heart been made to sink as I have gone through

the South and into the homes of the people and

found women who could converse intelligently on

Grecian history, who had studied geometry, could

analyze the most complex sentences, and yet

could not analyze the poorly cooked and still

more poorly served bread and fat meat that they

and their families were eating three times a

day.

It is little

trouble to find girls who can locate Peking and

the Desert of Sahara on an artificial globe; but

seldom can you find one who can locate on an

actual dinner table the proper place for the

carving knife and fork or the meat and

vegetables.

A short time ago,

in one of our Southern cities, a colored man

died who had received training as a skilled

mechanic during the days of slavery. By his

skill and industry he had built up a great

business as a house contractor and builder. In

this same city there are 35,000 colored people,

among them young men who have been well educated

in languages and literature, but not a single

one could be found who had been trained in

architectural and mechanical drawing that could

carry on the business which this ex-slave had

built up, and so it was soon scattered to the

wind.

Aside from the

work done in the institutions that I have

mentioned, you will find no colored men who have

been trained in the principles of architecture,

notwithstanding the vast majority of the race is

without homes. Here, then, are the three prime

conditions for growth, for civilization — food,

clothing, shelter — yet we have been the slaves

of form and custom to such an extent that we

have failed in a large measure to look matters

squarely in the face and meet actual needs. You

cannot graft a fifteenth-century civilization

onto a twentieth-century civilization by the

mere performance of mental gymnastics.

Understand, I speak in no fault-finding spirit,

but with a feeling of deep regret for what has

been done; but the future must be an improvement

on the past.

I have endeavored

to speak plainly in regard to the past, because

I fear that the wisest and most interested have

not fully comprehended the task which American

slavery has laid at the doors of the Republic.

Few, I fear, realize what is to be done before

the seven million of my people in the South can

be made a safe, helpful, progressive part of our

institutions. The South, in proportion to its

ability, has done well, but this does not change

facts.

Let me illustrate

what I mean by a single example. In spite of all

that has been done, I was in a county in Alabama

a few days ago where there are some thirty

thousand colored people and about seven thousand

whites; in this county not a single public

school for Negroes has been open this year

longer than three months, not a single colored

teacher has been paid more than fifteen dollars

a month for his teaching. Not one of these

schools was taught in a building worthy of the

name of schoolhouse. In this county the state or

public authorities do not own a dollar's worth

of school property — not a schoolhouse, a

blackboard, or a piece of crayon.

Each colored child had spent on him this year

for his education about fifty cents, while one

of your children had spent on him this year for

education not far from twenty dollars. And yet

each citizen of this county is expected to share

the burdens and privileges of our democratic

form of government just as intelligently and

conscientiously as the citizens of your beloved

Kings County. A vote in this county means as

much to the nation as a vote in the city of

Boston. Crime in this county is as truly an

arrow aimed at the heart of the government as

crime committed in your own streets. Do you know

that a single schoolhouse built this year in a

town near Boston to shelter about 300 students

has cost more for building alone than will be

spent for the education, including buildings,

apparatus, teachers, of the whole colored school

population of Alabama?

The commissioner

of education for the state of Georgia recently

reported to the state legislature that in the

state there were 200,000 children that had

entered no school the past year, and 100,000

more who were in school but a few days, making

practically 300,000 children between six and

sixteen years of age that are growing up in

ignorance in one Southern state.

The same report

state that outside of the cities and towns,

while the average number of schoolhouses in a

county is 60, all of these 60 schoolhouses are

worth in a lump sum less than $2,000, and the

report further adds that many of the

schoolhouses in Georgia are not fit for horse

stables. These illustrations, my friends, as far

as concerns the Gulf states, are not exceptional

cases or overdrawn.

I have referred to

industrial education as a means of fitting the

millions of my people in the South for the

duties of citizenship. Until there is industrial

independence it is hardly possible to have a

pure ballot. In the country districts of the

Gulf states it is safe to say that not more than

one black man in twenty owns the land he

cultivates. Where so large a proportion of the

people are dependent, live in other people's

houses, eat other people's food, and wear

clothes they have not paid for, it is a pretty

hard thing to tell how they are going to vote.

My remarks thus

far have referred mainly to my own race. But

there is another side. The longer I live and the

more I study the question, the more I am

convinced that it is not so much a problem as to

what you will do with the Negro as what the

Negro will do with you and your civilization.

In considering

this side of the subject, I thank God that I

have grown to the point where I can sympathize

with a white man as much as I can sympathize

with a Southern white man as much as I can

sympathize with a Northern white man. To me "a

man's a man for a' that and a' that." As bearing

upon democracy and education, what of your white

brethren in the South, those who suffered and

are still suffering the consequences of American

slavery for which both you and they are

responsible? You of the great and prosperous

North still owe to your unfortunate brethren of

the Caucasian race in the South, not less than

to yourselves, a serious and uncompleted duty.

What was the task you asked them to perform?

Returning to their destitute homes after years

of war to face blasted hopes, devastation, a

shattered industrial system, you asked them to

add to their own burdens that of preparing in

education, politics, and economics in a few

short years, for citizenship, four millions of

former slaves. That the South, staggering under

the burden, made blunders, and that in a measure

there has been disappointment, no one need be

surprised.

The educators, the

statesmen, the philanthropists have never

comprehended their duty toward the millions of

poor whites in the South who were buffeted for

two hundred years between slavery and freedom,

between civilization and degradation, who were

disregarded by both master and slave. It needs

no prophet to tell the character of our future

civilization when the poor white boy in the

country districts of the South receives one

dollar's worth of education and your boy twenty

dollars' worth, when one never enters a library

or reading room and the other has libraries and

reading rooms in every ward and town. When one

hears lectures and sermons once in two months

and the other can hear a lecture or sermon every

day in the year.

When you help the

South you help yourselves. Mere abuse will not

bring the remedy. The times has come, it seems

to me, when in this matter we should rise above

party or race or sectionalism into the region of

duty of man to man, citizen to citizen,

Christian to Christian, and if the Negro who has

been oppressed and denied rights in a Christian

land can help you North and South to rise, can

be the medium of your rising into this

atmosphere of generous Christian brotherhood and

self-forgetfulness, he will see in it a

recompense for all that he has suffered in the

past.

Not very long ago

a white citizen of the South boastingly

expressed himself in public to this effect: "I

am now 46 years of age, but have never polished

my own boots, have never saddled my own horse,

have never built a fire in my own room, have

never hitched a horse." He was asked a short

time since by a lame man to hitch his horse, but

refused and told him to get a Negro to do it.

Our state law requires that a voter be required

to read the constitution before voting, but the

last clause of the constitution is in Latin and

the Negroes cannot read Latin, and so they are

asked to read the Latin clause and are thus

disfranchised, while the whites are permitted to

read the English portion of the constitution. I

do not quote these statements for the purpose of

condemning the individual or the South, for

though myself a member of a despised and

unfortunate race, I pity from the bottom of my

heart any of God's creatures whence such a

statement can emanate. Evidently here is a man

who, as far as mere book training is concerned,

is educated, for he boasts of his knowledge of

Latin, but, so far as the real purpose of

education is concerned — the making of men

useful, honest, and liberal — this man has never

been touched. Here is a citizen in the midst of

our republic, clothed in a white skin, with all

the technical signs of education, but who is as

little fitted for the highest purpose of life as

any creature found in Central Africa.

My friends, can we

make our education reach down far enough to

touch and help this man? Can we so control

science, art, and literature as to make them to

such an extent a means rather than an end; that

the lowest and most unfortunate of God's

creatures shall be lifted up, ennobled and

glorified; shall be a freeman instead of a slave

of narrow sympathies and wrong customs?

Some years ago a

bright young man of my race succeeded in passing

a competitive examination for a cadetship at the

United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. Says

the young man, Mr. Henry Baker, in describing

his stay at this institution: "I was several

times attacked with stones and was forced

finally to appeal to the officers, when a marine

was detailed to accompany me across the campus

and from the mess hall at meal times. My books

were mutilated, my clothes were cut and in some

instances destroyed, and all the petty

annoyances which ingenuity could devise were

inflicted upon me daily, and during seamanship

practice aboard the Dale attempts were

often made to do me personal injury while I

would be aloft in the rigging. No one ever

addressed me by name. I was called the Moke

usually, the Nigger for variety. I was shunned

as if I were a veritable leper, and received

curses and blows as the only method my

persecutors had of relieving the monotony."

Not once during the two years, with one

exception, did any one of the more than 400

cadets enrolled ever come to him with a word of

advice, counsel, sympathy, or information, and

he never held conversation with any one of them

for as much as five minutes during the whole

course of his experience at the academy, except

on occasions when he was defending himself

against their assaults.

The one exception

was in the case of a Pennsylvania boy, who

stealthily brought him a piece of his birthday

cake at twelve o'clock one night. The act so

surprised Baker that his suspicions were

aroused, but these were dispelled by the donor,

who read to him a letter which he had received

from his mother, from whom the cake came, in

which she requested that a slice be given to the

colored cadet who was without friends.

I recite this incident not for the purpose

merely of condemning the wrong done a member of

my race; no, no, not that. I mention the case,

not for the one cadet, but for the sake of the

400 cadets, for the sake of the 400 American

families, the 400 American communities whose

civilization and Christianity these cadets

represented. Here were 400 and more picked young

men representing the flower of our country, who

had passed through our common schools and were

preparing themselves at public expense to defend

the honor of our country. And yet, with grammar,

reading, and arithmetic in the public schools,

and with lessons in the arts of war, the

principles of physical courage at Annapolis,

both systems seemed to have utterly failed to

prepare a single one of these young men for real

life, that he could be brave enough, Christian

enough, American enough, to take this poor

defenseless black boy by the hand in open

daylight and let the world know that he was his

friend.

Education, whether

of black man or white man, that gives one

physical courage to stand in front of the cannon

and fails to give him moral courage to stand up

in defense of right and justice is a failure.

With all that the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and

Sciences stands for in its equipment, its

endowment, its wealth and culture, its

instructors, can it produce a mother that will

produce a boy that will not be ashamed to have

the world know that he is a friend to the most

unfortunate of God's creatures?

Not long ago a

mother, a black mother, who lived in one of your

Northern states, had heard it whispered around

in her community for years that the Negro was

lazy, shiftless, and would not work. So when her

boy grew to sufficient size, at considerable

expense and great self-sacrifice, she had her

boy thoroughly taught the machinist's trade. A

job was secured in a neighboring shop. With

dinner bucket in hand and spurred on by the

prayers of the now happy mother, the boy entered

the shop to begin his first day's work. What

happened? Had any one of the 20 white Americans

been so educated that he gave this stranger a

welcome into their midst? No, not this. Every

one of the 20 white men threw down his tools and

deliberately walked out, swearing that he would

not give a black man an opportunity to earn an

honest living. Another shop was tried, with the

same result, and still another and the same.

Today this promising and ambitious black man is

a wreck, a confirmed drunkard, with no hope, no

ambition.

My friends, who

blasted the life of this young man? On whose

hands does his blood rest? Our system of

education, or want of education, is responsible.

Can our public schools and colleges turn out a

set of men that will throw open the doors of

industry to all men everywhere, regardless of

color, so all shall have the same opportunity to

earn a dollar that they now have to spend a

dollar? I know a good many species of cowardice

and prejudice, but I know none equal to this. I

know not who is the worst, the ex-slaveholder

who perforce compelled his slave to work without

compensation, or the man who perforce compels

the Negro to refrain from working for

compensation.

My friends, we are

one in this country. The question of the highest

citizenship and the complete education of all

concerns nearly 10 million of my own people and

over 60 million of yours. We rise as you rise;

when we fall you fall. When you are strong we

are strong; when we are weak you are weak. There

is no power that can separate our destiny. The

Negro can afford to be wronged; the white man

cannot afford to wrong him. Unjust laws or

customs that exist in many places regarding the

races injure the white man and inconvenience the

Negro. No race can wrong another race simply

because it has the power to do so without being

permanently injured in morals.

The Negro can

endure the temporary inconvenience, but the

injury to the white man is permanent. It is for

the white man to save himself from his

degradation that I plead. If a white man steals

a Negro's ballot it is the white man who is

permanently injured. Physical death comes to the

one Negro lynched in a county, but death of the

morals — death of the soul — comes to the

thousands responsible for the lynching. We are a

patient, humble people. We can afford to work

and wait. There is plenty in this country for us

to do. Away up in the atmosphere of goodness,

forbearance, patience, long-suffering, and

forgiveness the workers are not many or

overcrowded. If others would be little we can be

great. If others would be mean we can be good.

If others would push us down we can help push

them up. Character, not circumstances, makes the

man.

It is more

important that we be prepared for voting than

that we vote, more important that we be prepared

to hold office than that we hold office, more

important that we be prepared for the highest

recognition than that we be recognized.

Those who fought

and died on the battlefield performed their duty

heroically and well, but a duty remains for you

and me. The mere fiat of law could not make an

ignorant voter an intelligent voter; could not

make one citizen respect another; these results

come to the Negro, as to all races, by beginning

at the bottom and working up to the highest

civilization and accomplishment. In the economy

of God, there can be but one standard by which

an individual can succeed, there is but one for

a race. This country demands that every race

measure itself by the American standard. By it a

race must rise or fall, succeed or fail, and in

the last analysis mere sentiment counts but

little. During the next half-century and more my

race must continue passing through the severe

American crucible.

We are to be

tested in our patience, in our forbearance, our

power to endure wrong, to withstand temptation,

to succeed, to acquire and use skill, our

ability to compete, to succeed in commerce; to

disregard the superficial for the real, the

appearance for the substance; to be great and

yet the servant of all. This, this is the

passport to all that is best in the life of our

republic, and the Negro must possess it or be

debarred. In working out our destiny, while the

main burden and center of activity must be with

us, we shall need in a large measure the help,

the encouragement, the guidance that the strong

can give the weak. Thus helped, we of both races

in the South shall soon throw off the shackles

of racial and sectional prejudice and rise above

the clouds of ignorance, narrowness, and

selfishness into that atmosphere, that pure

sunshine, where it will be our highest ambition

to serve man, our brother, regardless of race or

past conditions.

More History

|

|