|

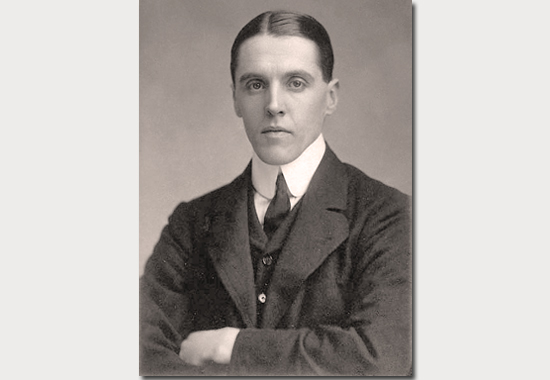

SMART AND PROVOCATIVE — FREDERICK

EDWIN SMITH

Maiden Speech

|

|

Go here for more about

F.E.

Smith. F.E.

Smith.

Go here for more about

F.E.

Smith's Maiden Speech. F.E.

Smith's Maiden Speech.

Photo above:

F.E. Smith, First Earl of Birkenhead. Photographer: Elliott

& Fry.

It follows the full text transcript of

F.E. Smith's first parliamentary speech,

delivered in the House of Commons at London, UK —

March 12, 1906. |

The principles and practice of

free trade had been previously debated, the debate had been

adjourned and was

resumed on March 12.

|

Mr. F. E. Smith:

Mr. Speaker, sir, |

in whatever

section of the House hon. members may sit, or

however profoundly they may differ from the

economic views which underlie the remarks of the

hon. member for Blackburn [Mr. Snowden], they

will all, at least, desire to join in a tribute

to the sincerity and ability displayed in the

speech he has just delivered. Speaking for

myself, I confess that I have been struck by the

admissions which have been made by those hon.

members who have spoken in favor of this

resolution.

I venture to ask

hon. members on the ministerial side, at the

height of their triumph, to consider for a

moment what is implicitly involved in their

concessions. The hon. member for Blackburn has

just told the House that sixty years of free

trade have absolutely failed to ameliorate the

condition of the working classes. That is a

statement upon which the Opposition have reached

some degree of agreement with the hon. member.

Where, however, we

part company with him, is not upon the great and

growing importance of still further ameliorating

the condition of the working classes, but upon

the feasibility of effectively assisting

thirteen million people on the verge of

starvation by a revision of railway rates, by

unexplained dealings with mine-owners, or by

loose, mischievous, and predatory proposals

affecting those who happen to own land.

The hon. gentleman

spoke with bitterness almost with contempt of

persons possessing large incomes. I would

entreat hon. members to make quite sure that

they have cleared their minds of cant upon this

question. When I hear vague and general

proposals put forward at the expense of large

incomes, without any precise explanation as to

the principle upon which, or the extent to which

those incomes are to be appropriated or tapped

for the service of those who are less fortunate,

I should like to make an elementary observation,

that there are very few members in this House,

whether in Opposition or on the benches opposite

or below the gangway, whose principal business

occupation it is not to provide themselves with

as large an income as they honestly can.

If there is one

profession to which that charge cannot be

applied, it is, perhaps, the profession to which

I myself belong. I, therefore, attach little

importance to disparaging observations upon the

rich, either from the hon. gentleman or from

anyone else. Nor do I believe that the policy of

unduly burdening the rich will be found on a

just consideration of the action and interaction

of economic forces to be of real advantage to

the poor. Labour, after all, is immobile,

whereas capital is always fugitive.

What other

remedies has the hon. gentleman for the evils

which he so clearly appreciates? He and his

friends are alike barren in suggestion.

Unemployment yearly grows chronic over a larger

area, while a Parliament of Free Importers

celebrates in academic resolutions the economic

system which has depopulated rural England, has

filled the emigrant steamers with fugitives from

these happy shores, and has aggravated the evils

of the most revolting slums in Christendom.

The progress of

tonight's debate makes one profoundly conscious

of the constructive shortcomings of the

Cobdenism of today. I myself am a perfectly

unrepentant member of the Tariff Reform League.

I do not know how many members of the league

there may be in the House; it may be that a

division would show that they are not more

numerous than the representatives of the Liberal

League. I have, at least, the satisfaction of

reflecting that, if tariff reform is found not

to be a winning horse, I have not necessarily

compromised my political future. I have in hon.

and right hon. gentlemen opposite an admirable

example of how to cut the painter of a similar

league, with the maximum of political

advancement, and the minimum of fidelity to a

founder. Such a model of chivalrous loyalty is

of great value to a young member of Parliament.

I suppose the

resolution has been charitably designed to call

attention to differences existing or supposed to

exist in the Opposition. I should have thought

that we might have looked to hon. gentlemen

opposite for a little more charity. Hon.

gentlemen opposite have had analogous

difficulties. The question of when a tariff

becomes protective is no doubt difficult, but

not more so than the conundrum "When is a slave

not a slave?" or the problem when, if ever,

preferential treatment should be given to Roman

Catholic schools.

All great

political parties have skeletons in the

cupboard, some with manacles on, and some with

only their hands behind their backs. The quarrel

I have with hon. gentlemen opposite is that they

show an astonishing indelicacy in attempting to

drag our skeleton into the open. Not satisfied

with tomahawking our colleagues in the country,

they ask the scanty remnant in the House to join

in the scalp dance.

I do not think we

can complain of the tone of a single speech

which has been made from the opposite side of

the House. We were particularly pleased with the

remarks which fell from the hon. member for East

Toxteth [Mr. Austin Taylor], for he entered the

House, not like his new colleagues, on the crest

of the wave, but rather by means of an opportune

dive. Every one in the House will appreciate his

presence, because there can be no greater

compliment paid to the House by a member, than

that he should be in our midst, when his heart

is far away, and it must be clear to all who

know the hon. member's scrupulous sense of

honor, that his desire must be at the present

moment to be amongst his constituents, who are

understood to be at least as anxious to meet

him.

The resolution

before the House consists of two parts. In the

first, we are asked to recognize the merits of

what is described on an obscure prescriptive

principle as free trade, and, in the second, we

are invited to register the proposition that the

country gave an unqualified verdict in its

favor.

The word

"unqualified" is in itself ambiguous, and may

have more than one meaning. If we say that a man

is an unqualified slave, we mean that his

condition can be honestly described as

completely servile, and not, merely, as

semi-servile. If, on the other hand, we say that

a man is an unqualified medical practitioner, or

an unqualified Under-Secretary, we mean that he

is not entitled to any particular respect,

because he has not passed through the normal

period of training, or preparation. It is, on

the whole, probable that the word is used in the

first sense in the present motion.

But, perhaps, it

is necessary to distinguish even further. When

hon. gentlemen opposite are successful at the

polls, it is probably used in the first sense.

In the comparatively few cases in which I and my

friends were successful, it is used in the

second. Birmingham, under circumstances which

will never be effaced from the memory of hon.

gentlemen, on whichever side of the House they

sit, displayed the rare and beautiful quality of

political constancy, and voted in all its

divisions for tariff reform. [Laughter.] The

result is sneered at, in the spirit of the

laughter which we have just heard, as a triumph

for Tammanyism, or, more profoundly analyzed by

an eminent Nonconformist divine, as an instance

of that mysterious dispensation, which

occasionally permits the ungodly to triumph.

Hon. gentlemen

opposite are, in fact, very much more successful

controversialists than hon. members on this side

of the House. It is far easier, if one is a

master of scholarly irony, and of a charming

literary style, to describe protection as a

"stinking rotten carcass" than to discuss

scientifically whether certain limited proposals

are likely to prove protective in their

incidence. It is far easier, if one has a strong

stomach, to suggest to simple rustics, as the

President of the Board of Trade [Mr.

Lloyd-George] did, that, if the Tories came into

power, they would introduce slavery on the hills

of Wales.

Mr. Lloyd-George: I did not say that.

Mr. F.E. Smith:

The right hon.

gentleman would, no doubt, be extremely anxious

to forget it, if he could. But, anticipating a

temporary lapse of memory, I have in my hand the

Manchester Guardian of January 16, 1906, which

contains a report of his speech. The right hon.

gentleman said:

"What would

they say to introducing Chinamen at 1s. a

day into the Welsh quarries? Slavery on the

hills of Wales! Heaven forgive me for the

suggestion!"

I have no means of

judging how Heaven will deal with persons, who

think it decent to make such suggestions. The

distinction drawn by the right hon. gentleman is

more worthy of the county court than of the

Treasury Bench. I express a doubt whether any

honest politician will ever acquit the right

hon. gentleman of having deliberately given the

impression to those he thus addressed that, if

the Conservative party were returned, the hills

of Wales would be polluted by conditions of

industrial slavery.

The alternative

construction is that the right hon. gentleman

thought it worth his while, in addressing

ignorant men [Cries of " No"] —

In relation to the

right hon. gentleman they are ignorant. Is that

disputed? — to put before ignorant men an

abstract and academic statement as to Chinese

labor on the hills of Wales. If he did not mean

his hearers to draw the false but natural

inference, why make any reference to Chinese

slavery as a conceivable prospect on the hills

of Wales?

Was even

Manchester won on the free trade issue? [Cries

of " Yes."] I hear hon. gentlemen opposite say

"Yes." I think they must be from the south of

England. If Manchester was won on the free trade

issue, perhaps hon. gentlemen will explain why

repeated meetings were devoted to the less

effective and attractive cry, and why specialist

speakers like Mr. Creswell were brought down to

discourse to the electors on the evils of

Chinese slavery.

Mr. Speaker, I am

not unaware that, owing to the eccentricities of

municipal geography, Salford is not,

technically, a part of Manchester, but a Salford member is near

enough to wear the green turban of a pilgrimage

to Cobden's Mecca. The hon. member for Salford

[Mr. Hilaire Belloc]

has stated that he was returned to the House,

pledged to urge insistently on the Government,

which profited by a false cry, the immediate

repatriation of the coolies now on the Rand.

Shall I be told that in that case the electors

were giving an unqualified verdict for Cobdenism, or for

what is called in this resolution free trade?

I do not think

that the hon. and learned gentleman, who fought

so strenuously in East Manchester [Mr. T. G. Horridge], will get up and tell the House

that in his constituency the verdict was an unqualified one for free trade. I have some choice

specimens of the bread that he threw on the

waters in order, I suppose, to elicit this unqualified verdict.

He is reported, in

the Manchester Guardian of 13th January, to have said

that the Chinese had not been the means of

bringing one single piece of white labor to

South Africa. The hon. and learned gentleman

appears to think that white labor is introduced

in slabs. He said:

"You are voting, if you

vote for Mr. Balfour, for the exclusion of white

labor from South Africa"

— not for Cobdenism.

The hon. gentleman continued: "Where was that

thing going to stop?"

Mr. Speaker, this is

precisely what we should like to know today. "Were they going to have Chinamen working in the

mills at Bradford? Let the people of this

division show by their votes" — what? Their

devotion to free imports? No — "That they would

have none of this wretched coolie labor in

South Africa, and strike a blow for freedom

tomorrow at the polls."

There is an

interesting point of analogy between the hon.

and learned gentleman and the "wretched coolies," of whom he has so low an opinion. Today he is

in, and they are in, and it rather looks as if

they are going to remain in as long as he and

his friends.

It was in this way that the poorer districts of

Manchester were captured — Cobden's Manchester.

Did the hon. member, the Under-Secretary for

the Colonies [Mr. Winston Churchill], use his

great and growing

local influence on behalf of what in his heart

and conscience he knew to be the truth? I say

"on behalf of what he knew to be the truth,"

because the hon. member is reported in the Manchester Guardian, as having said on June 12,

1903, that he was quite sure that supplies of

native or Chinese labor would have to be

obtained, and ought to be obtained for the mines

in the interests of South Africa as a whole.

I

will not weary the House with the whole of the

Under-Secretary's peroration. I rather think it

has been at the disposal of both parties in

the House before undertaking a provincial

tour.

Mr. Speaker, it is easy for the

Under-Secretary to come to the House and state

in the debate on the Address that he attempted

to confine the issue at the election to the

single point of Cobdenism, to the single merits

of free trade, and that he had therefore no

responsibility for an incendiary campaign. To

that I reply, proximus ucalegon ardebat, which I

may venture to construe proximus, in an adjacent

constituency; ucalegon, the hon. and learned

gentleman [Mr. T. G. Horridge]; ardebat, was letting off Chinese

crackers.

The Under-Secretary did not then

explain that the coolie processions, which his

learned friend was so forward in organizing,

were merely contributions to the problem of the

unemployed, or that slavery was a terminological inexactitude. He profited by the storm

of generous anger which these falsehoods, being believed, excited

among the Lancashire democracy. He took what he

could get, and thanked God for it. Mr. Speaker,

the role of the receiver of stolen reputations

is rather less respectable in the eyes of the

man of spirit, than that of the principal thief.

I must, however,

in candor admit that the question of cheap food

was brought forward in many constituencies with

great persistency and ingenuity. The hon. member

for North Paddington [Mr. Chiozza Money], with an infinitely

just appreciation of his own controversial

limitations, relied chiefly on an intermittent

exhibition of horse sausages as a witty,

graceful, and truthful sally at the expense of

the great German nation.

I do not understand

what the Secretary of State for War means by

saying that the Liberal Party has no ideas. The

Liberal League always was a drag upon the holy

wheel of progress. In Wales, apparently, they

like it strong, and the President of the Board

of Trade [Mr. Lloyd-George] informed one favored audience how

large a part horse-flesh plays in the simple

diet of the German home. The same speaker is

never tired of maintaining that protection has

tainted and corrupted German public life. I

understand that any trade negotiations which may

become necessary with Germany must be conducted

through the right hon. gentleman. I am not

sanguine of the outcome. If you have a difficult

business transaction to carry through with a

competitor, a prudent reflection would perhaps

suggest that it is unwise to describe

him publicly as a corrupt scoundrel,

subsisting principally upon the flesh of horses.

I do not suppose that, now the fight is over,

now that the strategy has been so brilliantly successful, away from the

license of the

platform, in the House, where their statements

can be met and dealt with, hon. gentlemen will

deny that the immediate effect of a 2s. duty on

corn will be an illimitable development of

colonial acreage suitable for the growth of

wheat. [Cries of " Oh, oh," and loud derisive

laughter.] I am astonished to hear sounds of

derisive dissent, for I rather thought that at

the time when Lord Rosebery, from whom I was

quoting with verbal precision, made that

prediction to frighten the English farmer from

tariff reform, hon. gentlemen were in the same

tabernacle, or furrow, or whatever was the

momentary rendezvous of the Liberal party.

At

the moment, hon. gentlemen will recollect, the

other ship looked like sinking; there was a

temporary slump in the "methods of barbarism "

section. I venture to ask hon. gentlemen, to

tell us in the candor of victory, whether any

one really doubts that Canada would, in a few

years, be able, under judicious stimulation, to

supply the whole English consumption of wheat?

[Cries of " No, no."] Sir Wilfrid Laurier says

it can, and hon. gentlemen say it cannot.

Perhaps the Under-Secretary for the Colonies

[Mr. Winston Churchill],

whom I am sorry not to see in his place, will

put Sir Wilfrid Laurier on the black list with

Lord Milner, [Mr. Churchill had recently stated

in the House of Commons that he did not feel

called upon to protect Lord Milner in the

future.] and refuse to protect

him any longer.

Does the House recollect La

Fontaine's insect, the species is immaterial,

which expired under the impression that it had

afforded a lifelong protection to the lion, in

whose carcass its life was spent?

There is hardly a

Canadian statesman who does not go further than

Sir Wilfrid Laurier in the direction of tariff

reform. Earlier in the debate some reference was

made to Mr. Fisher, and I desire to speak of Mr.

Fisher's views and ability with great respect;

it is not necessary to vilify any colonial

politician with whom you disagree. But, in

Canada, Mr. Fisher and Mr. Goldwin Smith are in

a minority of two, and Canada has almost reached

the stage one day, I hope, to be attained in

England of exhibiting Free Importers in her

museums.

An official report, ordered by the

United States Government in 1902, found the

district contributory to Winnipeg capable,

within the lives of persons still living, of

supplying enough wheat to provide for the

consumption of the world. If this be true, or

half true, what becomes of the nightmare of

apprehension, which has made hon. gentlemen

opposite so infinitely tedious for the last few

years? If an illimitable supply of Canadian corn

is coming in untaxed, what becomes of the little

loaf? Once again, I recognize in hon. gentlemen opposite our electioneering masters, and I

compliment them, if not on an unqualified

verdict, at any rate, upon an unqualified

inexactitude.

Some hon.

gentleman ventured upon a more ambitious line of

argument, and, in doing so, permanently enriched

the economic knowledge of the country. We were told that

it is not a disadvantage, but rather an

advantage, that English factories should be

removed abroad. Perhaps some consistent logician

will shortly introduce a Bill offering bounties

to capitalists who remove their works abroad.

Let us by all means drive from the country

everybody who has work to give, and then wave

banners, like the hon. member for Merthyr Tydvil

[Mr. Keir Hardie],

in the "Right to Work Committee."

A

fortnight ago hon. gentlemen opposite, calling

in aid every resource of pathos, indulged in

beautiful sentiments about the feeding of starving

children. If the matter had been pressed to a

division, I should have voted with them, but I

should have done so without prejudice to my convictions as to the economic system which gave

rise to the necessity. I should like to know how

hon. gentlemen opposite explain the growing

poverty of the poor. [Ministerial cries of " The

War."]

Since this House

of Commons met, we have heard a great deal about

the war. I would suggest to hon. gentlemen, as a

humble admirer of their methods, that, if they

wish for targets in that matter, they ought to

aim, not at the Opposition Benches, but at

right hon. gentlemen who sit on the Front

Government Bench.

Hon. gentle men opposite

should remember that the present Secretary of

State for War [Mr. Haldane] justly observed that the Boers

waged the war, not only with the object of

maintaining their independence, but also to

undermine our authority in South Africa. And

the present Attorney-General [Sir John Lawson

Walton] said that the war could be shown to

be as just, as it was inevitable, and to have

been defensible on the grounds of freedom.

The

circumstances of which you complain were

anterior to the war. While the only panacea

which hon. gentlemen opposite can suggest is

the employment of broken-down artisans in

planting trees, and constructing dams against

the encroachment of the sea, the Unionist party

need not be discouraged by their reverses at the

polls. We will say of the goddess who presides

over the polls, as Dryden said of Fortune in

general:

I can enjoy her

while she's kind;

But when she dances in the

wind,

And shakes her wings, and will not stay,

I

puff the prostitute away.

Was the verdict

unqualified, having regard to the aggregate

number of votes polled on behalf of Liberal

members? The votes polled at the last election

for Liberal, Labour, and Nationalist candidates were 3,300,000, while those polled for

tariff reform candidates and other gentlemen

sitting around me were 2,500,000. [Cries of " No

! Not true ! "] I gather that it is suggested

that my figures are wrong. [Cries of " Yes."]

They very probably are. I took them from the

Liberal Magazine.

Perhaps the Minister of

Education [Mr. Birrell, formerly Chairman of the

Liberal Publications Department] was responsible for them, before

he gave up the hecatomb line of business for the

Christian toleration and charity department. I

venture to suggest to hon. gentlemen opposite,

that the figures I have quoted, so far as they

are accurate, are not altogether discouraging to those

who, for the first time after so many years of

blind dogma, have challenged the verdict of the

country on the issue of tariff reform.

What

would hon. gentlemen who represent Ireland say,

if it was suggested that they were Cobdenites?

Will one of them get up to say that Cobdenism

has brought prosperity or success to Ireland, or

to guarantee that a representative Irish

Parliament would not introduce a general tariff

on foreign manufactured articles? The jury who

gave this unqualified verdict are unaccountably

silent. The spectacle of the Cobdenite hen

cackling over a protectionist duckling of her

own hatching in Ireland would add a partially

compensating element of humor even to the prospect of Home Rule.

The Irish, and I may add, the

Indian case for tariff reform were both once and

for all conceded by the " infant community " admission of Adam Smith. Why do we force upon

India and Ireland alike a system, of which every

honest man knows that whether it be good or bad

for us it denies to them the right to develop

and mature their nascent industries upon the

lines in which they themselves most earnestly

believe, and in which every country in the world

except Great Britain believes?

The answer is as

short, as it is discreditable. We perpetuate

this tyranny, in order that our Indian and Irish

fellow-subjects may be forced to buy from our

manufacturers articles which they would

otherwise attempt to manufacture for themselves. In other words, we perpetuate in these

two cases a compulsory and unilateral trade

preference demonstrably the fruit of selfishness

at the sacrifice of a voluntary and bilateral

preference, based deep and

strong upon mutual interest and mutual

affection.

I have heard the

majority on the other side of the House

described as the pure fruit of the Cobdenite

tree. I should rather say that they were begotten by Chinese slavery out of passive

resistance, by a rogue sire out of a dam that

roared. I read a short time ago that the Free

Church Council claimed among its members as many

as two hundred of hon. gentlemen opposite.

[Ministerial cries of " Oh ! "]

The Free Church Council gave thanks publicly for

the fact that Providence had inspired the

electors with the desire and the discrimination

to vote on the right side.

Mr. Speaker, I do

not, more than another man, mind being cheated

at cards. But I find it a little nauseating if

my opponent then proceeds to ascribe his success

to the favor of the Most High. What the future

of this Parliament has in store for right hon.

and hon. gentlemen opposite I do not know, but I

hear that the Government propose to deny to the

Colonial Conference of 1907 free discussion on

the subject which the House is now debating, so

as to prevent the statement of unpalatable

truths.

I know that I am the insignificant

representative of an insignificant numerical

minority in this House, but I venture to warn

the Government that the people of this country

will neither forget nor forgive a party which,

in the heyday of its triumph, denies to the

infant Parliament of the Empire one jot or tittle of that ancient liberty of speech, which

our predecessors in this House vindicated for

themselves at the point of the sword.

More History

|