|

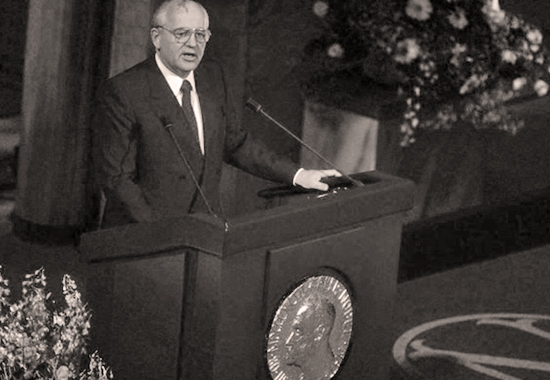

DELIVERING HIS DELAYED NOBEL LECTURE

- MIKHAIL GORBACHEV 1991

Gorbachev's Nobel Lecture

Go here for more about

Mikhail Gorbachev.

Mikhail Gorbachev.

Go here for more about

Gorbachev's Nobel Lecture.

Gorbachev's Nobel Lecture.

It follows the English

translation of the full text transcript of

Mikhail Gorbachev's Nobel Lecture, delivered at

Oslo, Norway - June 5, 1991.

|

Mr. Chairman,

Ladies and

Gentlemen, |

This moment is no

less emotional for me than the one when I first

learned about the decision of the Nobel

Committee. For on similar occasions great men

addressed humankind, men famous for their

courage in working to bring together morality

and politics. Among them were my compatriots.

The award of the Nobel Peace Prize makes one

think once again about a seemingly simple and

clear question: What is peace?

Preparing for my address I found in an old

Russian encyclopedia a definition of "peace" as

a "commune" - the traditional cell of Russian

peasant life. I saw in that definition the

people's profound understanding of peace as

harmony, concord, mutual help, and cooperation.

This understanding is embodied in the canons of

world religions and in the works of philosophers

from antiquity to our time. The names of many of

them have been mentioned here before. Let me add

another one to them. Peace "propagates wealth

and justice, which constitute the prosperity of

nations;" a peace which is "just a respite from

wars ... is not worthy of the name;" peace

implies "general counsel". This was written

almost 200 years ago by Vasiliy Fyodorovich

Malinovskiy - the dean of the Tsarskoye Selo

Lyceum at which the great Pushkin was educated.

Since then, of course, history has added a great

deal to the specific content of the concept of

peace. In this nuclear age it also means a

condition for the survival of the human race.

But the essence, as understood both by the

popular wisdom and by intellectual leaders, is

the same.

Today, peace means the ascent from simple

coexistence to cooperation and common creativity

among countries and nations.

Peace is movement towards globality and

universality of civilization. Never before has

the idea that peace is indivisible been so true

as it is now.

Peace is not unity in similarity but unity in

diversity, in the comparison and conciliation of

differences.

And, ideally, peace means the absence of

violence. It is an ethical value. And here we

have to recall Rajiv Gandhi, who died so

tragically a few days ago.

I consider the decision of your Committee as a

recognition of the great international

importance of the changes now under way in the

Soviet Union, and as an expression of confidence

in our policy of new thinking, which is based on

the conviction that at the end of the twentieth

century force and arms will have to give way as

a major instrument in world politics.

I see the decision to award me the Nobel Peace

Prize also as an act of solidarity with the

monumental undertaking which has already placed

enormous demands on the Soviet people in terms

of efforts, costs, hardships, willpower, and

character. And solidarity is a universal value

which is becoming indispensable for progress and

for the survival of humankind.

But a modern state has to be worthy of

solidarity, in other words, it should pursue, in

both domestic and international affairs,

policies that bring together the interests of

its people and those of the world community.

This task, however obvious, is not a simple one.

Life is much richer and more complex than even

the most perfect plans to make it better. It

ultimately takes vengeance for attempts to

impose abstract schemes, even with the best of

intentions. Perestroika has made us understand

this about our past, and the actual experience

of recent years has taught us to reckon with the

most general laws of civilization.

This, however, came later. But back in

March-April 1985 we found ourselves facing a

crucial, and I confess, agonizing choice. When I

agreed to assume the office of the General

Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet

Union Central Committee, in effect the highest

State office at that time, I realized that we

could no longer live as before and that I would

not want to remain in that office unless I got

support in undertaking major reforms. It was

clear to me that we had a long way to go. But of

course, I could not imagine how immense were our

problems and difficulties. I believe no one at

that time could foresee or predict them.

Those who were then governing the country knew

what was really happening to it and what we

later called zastoi, roughly translated

as "stagnation". They saw that our society was

marking time, that it was running the risk of

falling hopelessly behind the technologically

advanced part of the world. Total domination of

centrally-managed state property, the pervasive

authoritarian-bureaucratic system, ideology's

grip on politics, monopoly in social thought and

sciences, militarized industries that siphoned

off our best, including the best intellectual

resources, the unbearable burden of military

expenditures that suffocated civilian industries

and undermined the social achievements of the

period since the Revolution which were real and

of which we used to be proud - such was the

actual situation in the country.

As a result, one of the richest countries in the

world, endowed with immense overall potential,

was already sliding downwards. Our society was

declining, both economically and intellectually.

And yet, to a casual observer the country seemed

to present a picture of relative well-being,

stability and order. The misinformed society

under the spell of propaganda was hardly aware

of what was going on and what the immediate

future had in store for it. The slightest

manifestations of protest were suppressed. Most

people considered them heretical, slanderous and

counter-revolutionary.

Such was the situation in the spring of 1985,

and there was a great temptation to leave things

as they were, to make only cosmetic changes.

This, however, meant continuing to deceive

ourselves and the people.

This was the domestic aspect of the dilemma then

before us. As for the foreign policy aspect,

there was the East-West confrontation, a rigid

division into friends and foes, the two hostile

camps with a corresponding set of Cold War

attributes. Both the East and the West were

constrained by the logic of military

confrontation, wearing themselves down more and

more by the arms race.

The mere thought of dismantling the existing

structures did not come easily. However, the

realization that we faced inevitable disaster,

both domestically and internationally, gave us

the strength to make a historic choice, which I

have never since regretted.

Perestroika, which once again is returning our

people to commonsense, has enabled us to open up

to the world, and has restored a normal

relationship between the country's internal

development and its foreign policy. But all this

takes a lot of hard work. To a people which

believed that its government's policies had

always been true to the cause of peace, we

proposed what was in many ways a different

policy, which would genuinely serve the cause of

peace, while differing from the prevailing view

of what it meant and particularly from the

established stereotypes as to how one should

protect it. We proposed new thinking in foreign

policy.

Thus, we embarked on a path of major changes

which may turn out to be the most significant in

the twentieth century, for our country and for

its peoples. But we also did this for the entire

world.

I began my book about perestroika and the new

thinking with the following words: "We want to

be understood". After a while I felt that it was

already happening. But now I would like once

again to repeat those words here, from this

world rostrum. Because to understand us really -

to understand so as to believe us - proved to be

not at all easy, owing to the immensity of the

changes under way in our country. Their

magnitude and character are such as to require

in-depth analysis. Applying conventional wisdom

to perestroika is unproductive. It is also

futile and dangerous to set conditions, to say:

We'll understand and believe you, as soon as

you, the Soviet Union, come completely to

resemble "us", the West.

No one is in a position to describe in detail

what perestroika will finally produce. But it

would certainly be a self-delusion to expect

that perestroika will produce "a copy" of

anything.

Of course, learning from the experience of

others is something we have been doing and will

continue to do. But this does not mean that we

will come to be exactly like others. Our State

will preserve its own identity within the

international community. A country like ours,

with its uniquely close-knit ethnic composition,

cultural diversity and tragic past, the

greatness of its historic endeavors and the

exploits of its peoples - such a country will

find its own path to the civilization of the

twenty-first century and its own place in it.

Perestroika has to be conceived solely in this

context, otherwise it will fail and will be

rejected. After all, it is impossible to "shed"

the country's thousand-year history - a history,

which, we still have to subject to serious

analysis in order to find the truth that we

shall take into the future.

We want to be an integral part of modern

civilization, to live in harmony with mankind's

universal values, abide by the norms of

international law, follow the "rules of the

game" in our economic relations with the outside

world. We want to share with all other peoples

the burden of responsibility for the future of

our common house.

A period of transition to a new quality in all

spheres of society's life is accompanied by

painful phenomena. When we were initiating

perestroika we failed to properly assess and

foresee everything. Our society turned out to be

hard to move off the ground, not ready for major

changes which affect people's vital interests

and make them leave behind everything to which

they had become accustomed over many years. In

the beginning we imprudently generated great

expectations, without taking into account the

fact that it takes time for people to realize

that all have to live and work differently, to

stop expecting that new life would be given from

above.

Perestroika has now entered its most dramatic

phase. Following the transformation of the

philosophy of perestroika into real policy,

which began literally to explode the old way of

life, difficulties began to mount. Many took

fright and wanted to return to the past. It was

not only those who used to hold the levers of

power in the administration, the army and

various government agencies and who had to make

room, but also many people whose interests and

way of life was put to a severe test and who,

during the preceding decades, had forgotten how

to take the initiative and to be independent,

enterprising and self-reliant.

Hence the discontent, the outbursts of protest

and the exorbitant, though understandable,

demands which, if satisfied right away, would

lead to complete chaos. Hence, the rising

political passions and, instead of a

constructive opposition which is only normal in

a democratic system, one that is often

destructive and unreasonable, not to mention the

extremist forces which are especially cruel and

inhuman in areas of inter-ethnic conflict.

During the last six years we have discarded and

destroyed much that stood in the way of a

renewal and transformation of our society. But

when society was given freedom it could not

recognize itself, for it had lived too long, as

it were, "beyond the looking glass".

Contradictions and vices rose to the surface,

and even blood has been shed, although we have

been able to avoid a bloodbath. The logic of

reform has clashed with the logic of rejection,

and with the logic of impatience which breeds

intolerance.

In this situation, which is one of great

opportunity and of major risks, at a high point

of perestroika's crisis, our task is to stay the

course while also addressing current everyday

problems - which are literally tearing this

policy apart - and to do it in such a way as to

prevent a social and political explosion.

Now about my position. As to the fundamental

choice, I have long ago made a final and

irrevocable decision. Nothing and no one, no

pressure, cither from the right or from the

left, will make me abandon the positions of

perestroika and new thinking. I do not intend to

change my views or convictions. My choice is a

final one.

It is my profound conviction that the problems

arising in the course of our transformations can

be solved solely by constitutional means. That

is why I make every effort to keep this process

within the confines of democracy and reforms.

This applies also to the problem of

self-determination of nations, which is a

challenging one for us. We are looking for

mechanisms to solve that problem within the

framework of a constitutional process; we

recognize the peoples' legitimate choice, with

the understanding that if a people really

decides, through a fair referendum, to withdraw

from the Soviet Union, a certain agreed

transition period will then be needed.

Steering a peaceful course is not easy in a

country where generation after generation of

people were led to believe that those who have

power or force could throw those who dissent or

disagree out of politics or even in jail. For

centuries all the country's problems used to be

finally resolved by violent means. All this has

left an almost indelible mark on our entire

"political culture", if the term is at all

appropriate in this case.

Our democracy is being born in pain. A political

culture is emerging - one that presupposes

debate and pluralism, but also legal order and,

if democracy is to work, strong government

authority based on one law for all. This process

is gaining strength. Being resolute in the

pursuit of perestroika, a subject of much debate

these days, must be measured by the commitment

to democratic change. Being resolute does not

mean a return to repression, diktat or the

suppression of rights and freedoms. I will never

agree to having our society split once again

into Reds and Whites, into those who claim to

speak and act "on behalf of the people" and

those who are "enemies of the people". Being

resolute today means to act within the framework

of political and social pluralism and the rule

of law to provide conditions for continued

reform and prevent a breakdown of the state and

economic collapse, prevent the elements of chaos

from becoming catastrophic.

All this requires taking certain tactical steps,

to search for various ways of addressing both

short- and long-term tasks. Such efforts and

political and economic steps, agreements based

on reasonable compromise, are there for everyone

to see. I am convinced that the One-Plus-Nine

Statement will go down in history as one such

step, as a great opportunity. [On April 23,

1991, nine presidents of Soviet republics plus

Gorbachev, President of the Soviet Union, (1+9),

agreed that within six months a new union treaty

and constitution would be formulated to

restructure the Soviet Union.]

Not all parts of

our decisions are readily accepted or correctly

understood. For the most part, our decisions are

unpopular; they arouse waves of criticism. But

life has many more surprises in store for us,

just as we will sometimes surprise it. Jumping

to conclusions after every step taken by the

Soviet leadership, after every decree by the

President, trying to figure out whether he is

moving left or right, backward or forward, would

be an exercise in futility and would not lead to

understanding.

We will seek answers to the questions we face

only by moving forward, only by continuing and

even radicalizing reforms, by consistently

democratizing our society. But we will proceed

prudently, carefully weighing each step we take.

There is already a consensus in our society that

we have to move towards a mixed market economy.

There are still differences as to how to do it

and how fast we should move. Some are in favor

of rushing through a transitional period as fast

as possible, no matter what. Although this may

smack of adventurism we should not overlook the

fact that such views enjoy support. People are

tired and are easily swayed by populism. So it

would be just as dangerous to move too slowly,

to keep people waiting in suspense. For them,

life today is difficult, a life of considerable

hardship.

Work on a new Union Treaty has entered its final

stage. Its adoption will open a new chapter in

the history of our multinational state.

After a time of rampant separatism and euphoria,

when almost every village proclaimed

sovereignty, a centripetal force is beginning to

gather momentum, based on a more sensible view

of existing realities and the risks involved.

And this is what counts most now. There is a

growing will to achieve consensus, and a growing

understanding that we have a State, a country, a

common life. This is what must be preserved

first of all. Only then can we afford to start

figuring out which party or club to join and

what God to worship.

The stormy and contradictory process of

perestroika, particularly in the past two years,

has made us face squarely the problem of

criteria to measure the effectiveness of State

leadership. In the new environment of a

multiparty system, freedom of thought,

rediscovered ethnic identity and sovereignty of

the republics, the interests of society must

absolutely be put above those of various parties

or groups, or any other sectoral, parochial or

private interests, even though they also have

the right to exist and to be represented in the

political process and in public life, and, of

course, they must be taken into account in the

policies of the State.

Ladies and gentlemen, international politics is

another area where a great deal depends on the

correct interpretation of what is now happening

in the Soviet Union. This is true today, and it

will remain so in the future.

We are now approaching what might be the crucial

point when the world community and, above all,

the States with the greatest potential to

influence world developments will have to decide

on their stance with regard to the Soviet Union,

and to act on that basis.

The more I reflect on the current world

developments, the more I become convinced that

the world needs perestroika no less than the

Soviet Union needs it. Fortunately, the present

generation of policy-makers, for the most part,

are becoming increasingly aware of this

interrelationship, and also of the fact that now

that perestroika has entered its critical phase

the Soviet Union is entitled to expect

large-scale support to assure its success.

Recently, we have been seriously rethinking the

substance and the role of our economic

cooperation with other countries, above all

major Western nations. We realize, of course,

that we have to carry out measures that would

enable us really to open up to the world economy

and become its organic part. But at the same

time we come to the conclusion that there is a

need for a kind of synchronization of our

actions towards that end with those of the Group

of Seven and of the European Community. [The

Group of Seven industrialized states include the

United States, Great Britain, France, Germany,

Japan, Canada and Italy. The European Community

is the economic and political association of

European nations.]

In other words, we

are thinking of a fundamentally new phase in our

international cooperation.

In these months much is being decided and will

be decided in our country to create the

prerequisites for overcoming the systemic crisis

and gradually recovering to a normal life.

The multitude of specific tasks to be addressed

in this context may be summarized within three

main areas:

- Stabilizing

the democratic process on the basis of a

broad social consensus and a new

constitutional structure of our Union as a

genuine, free, and voluntary federation.

- Intensifying

economic reform to establish a mixed market

economy based on a new system of property

relations.

- Taking

vigorous steps to open the country up to the

world economy through ruble convertibility

and acceptance of civilized "rules of the

game" adopted in the world market, and

through membership in the World Bank and the

International Monetary Fund.

These three areas are closely interrelated.

Therefore, there is a need for discussion in the

Group of Seven and in the European Community. We

need a joint program of action to be implemented

over a number of years.

If we fail to reach an understanding regarding a

new phase of cooperation, we will have to look

for other ways, for time is of the essence. But

if we are to move to that new phase, those who

participate in and even shape world politics

also must continue to change, to review their

philosophic perception of the changing realities

of the world and of its imperatives. Otherwise,

there is no point in drawing up a joint program

of practical action.

The Soviet leadership, both in the center and in

the republics, as well as a large part of the

Soviet public, understand this need, although in

some parts of our society not everyone is

receptive to such ideas. There are some

flag-wavers who claim a monopoly of patriotism

and think that it means "not getting entangled"

with the outside world. Next to them are those

who would like to reserve the course altogether.

That kind of patriotism is nothing but a

self-serving pursuit of one's own interests.

Clearly, as the Soviet Union proceeds with

perestroika, its contribution to building a new

world will become more constructive and

significant. What we have done on the basis of

new thinking has made it possible to channel

international cooperation along new, peaceful

lines. Over these years we have come a long way

in the general political cooperation with the

West. It stood a difficult test at a time of

momentous change in Eastern Europe and of the

search for a solution to the German problem. It

has withstood the crushing stress of the crisis

in the Persian Gulf. There is no doubt that this

cooperation, which all of us need, will become

more effective and indispensable if our

economies become more integrated and start

working more or less in synchronized rhythm.

To me, it is self-evident that if Soviet

perestroika succeeds, there will be a real

chance of building a new world order. And if

perestroika fails, the prospect of entering a

new peaceful period in history will vanish, at

least for the foreseeable future.

I believe that the movement that we have

launched towards that goal has fairly good

prospects of success. After all, mankind has

already benefited greatly in recent years, and

this has created a certain positive momentum.

The Cold War is over. The risk of a global

nuclear war has practically disappeared. The

Iron Curtain is gone. Germany has united, which

is a momentous milestone in the history of

Europe. There is not a single country on our

continent which would not regard itself as fully

sovereign and independent.

The USSR and the USA, the two nuclear

superpowers, have moved from confrontation to

interaction and, in some important cases,

partnership. This has had a decisive effect on

the entire international climate. This should be

preserved and filled with new substance. The

climate of Soviet-US trust should be protected,

for it is a common asset of the world community.

Any revision of the direction and potential of

the Soviet-US relationship would have grave

consequences for the entire global process.

The ideas of the Helsinki Final Act have begun

to acquire real significance, they are being

transformed into real policies and have found a

more specific and topical expression in the

Charter of Paris for a New Europe. [At the

meeting in Helsinki, Finland, in 1975, the final

acts were ratified of the Conference on Security

and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). In the

Helsinki accords, signed by 34 states, including

all European states except Albania, as well as

the United States and Canada, the signatories

settled European border problems and agreed to

respect the human rights of their citizens and

to take certain steps to promote international

cooperation. Subsequent meetings were held, the

last in Vienna, which ended in 1990. In November

1990 CSCE statesmen signed the Charter of Paris

for a New Europe, committing their countries to

democracy and human rights and recognizing no

East-West divisions.]

Institutional

forms of European security are beginning to take

shape. Real disarmament has begun. Its first

phase is nearing completion, and following the

signing, I hope shortly, of the START Treaty

[The Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the

United States and the USSR led to the START

treaty, which was signed at a Bush-Gorbachev

summit meeting in Moscow, July 30-31, 1991.],

the time will come to give practical

consideration to the ideas which have already

been put forward for the future.

There seems,

however, to be a need to develop a general

concept for this new phase, which would embrace

all negotiations concerning the principal

components of the problem of disarmament and new

ideas reflecting the changes in Europe, the

Middle East, Africa and Asia, a concept that

would incorporate recent major initiatives of

President Bush and President Mitterand.

[Francois Maurice Mitterand was then President

of France, George Bush President of the United

States.] We are now thinking about it.

Armed forces and military budgets are being

reduced. Foreign troops are leaving the

territories of other countries. Their strength

is diminishing and their composition is becoming

more defense-oriented. First steps have been

taken in the conversion of military industries,

and what seemed inconceivable is happening:

recent Cold War adversaries are establishing

cooperation in this area. Their military

officials exchange visits, show each other

military facilities that only recently used to

be top secret and together consider ways to

achieve demilitarization.

The information environment has changed beyond

recognition throughout Europe and in most of the

world, and with it, the scale and intensity and

the psychological atmosphere of communication

among people of various countries.

De-ideologizing relations among States, which we

proclaimed as one of the principles of the new

thinking, has brought down many prejudices,

biased attitudes and suspicions and has cleared

and improved the international atmosphere. I

have to note, however, that this process has

been more intensive and frank on our part than

on the part of the West.

I dare say that the European process has already

acquired elements of irreversibility, or at

least that conflicts of a scale and nature that

were typical of Europe for many centuries and

particularly in the twentieth century have been

ruled out.

Should it gain the necessary momentum, every

nation and every country will have at their

disposal in the foreseeable future the potential

of a community of unprecedented strength,

encompassing the entire upper tier of the globe,

provided they make their own contribution.

In such a context, in the process of creating a

new Europe, in which erstwhile "curtains" and

"walls" will be forever relegated to the past

and borders between States will lose their

"divisive" purpose, self-determination of

sovereign nations will be realized in a

completely different way.

However, our vision of the European space from

the Atlantic to the Urals is not that of a

closed system. Since it includes the Soviet

Union, which reaches to the shores of the

Pacific, and the transatlantic USA and Canada

with inseparable links to the Old World, it goes

beyond its nominal geographical boundaries.

The idea is not at all to consolidate a part of

our civilization on, so to say, a European

platform versus the rest of the world.

Suspicions of that kind do exist. But, on the

contrary, the idea is to develop and build upon

the momentum of integration in Europe, embodied

politically in the Charter of Paris for the

whole of Europe. This should be done in the

context of common movement towards a new and

peaceful period in world history, towards new

interrelationship and integrity of mankind. As

my friend Giulio Andreotti [Giulio Andreotti was

then Prime Minister of Italy] so aptly remarked

recently in Moscow, "East-West rapprochement

alone is not enough for progress of the entire

world towards peace. However, agreement between

them is a great contribution to the common

cause". Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Near

and Middle East, all of them, are to play a

great role in this common cause whose prospects

are difficult to forecast today.

The new integrity of the world, in our view, can

be built only on the principles of the freedom

of choice and balance of interests. Every State,

and now also a number of existing or emerging

regional interstate groups, have their own

interests. They are all equal and deserve

respect.

We consider it dangerously outdated when

suspicions are aroused by, for instance,

improved Soviet-Chinese or Soviet-German,

German-French, Soviet- US or US-Indian

relations, etc. In our times, good relations

benefit all. Any worsening of relations anywhere

is a common loss.

Progress towards the civilization of the 21st

century will certainly not be simple or easy.

One cannot get rid overnight of the heavy legacy

of the past or the dangers created in the

post-war years. We are experiencing a turning

point in international affairs and are only at

the beginning of a new, and I hope mostly

peaceful, lengthy period in the history of

civilization.

With less East-West confrontation, or even none

at all, old contradictions resurface, which

seemed of secondary importance compared to the

threat of nuclear war. The melting ice of the

Cold War reveals old conflicts and claims, and

entirely new problems accumulate rapidly.

We can already see many obstacles and dangers on

the road to a lasting peace, including:

- Increased

nationalism, separatism, and

disintegrational processes in a number of

countries and regions.

- The growing

gap in the level and quality of

socio-economic development between "rich"

and "poor" countries; dire consequences of

the poverty of hundreds of millions of

people, to whom informational transparency

makes it possible to see how people live in

developed countries. Hence, the

unprecedented passions and brutality and

even fanaticism of mass protests. Poverty is

also the breeding ground for the spread of

terrorism and the emergence and persistence

of dictatorial regimes with their

unpredictable behavior in relations among

States.

- The

dangerously rapid accumulation of the

"costs" of previous forms of progress, such

as the threat of environmental catastrophe

and of the depletion of energy and primary

resources, uncontrollable overpopulation,

pandemics, drug abuse, and so on.

- The gap

between basically peaceful policies and

selfish economies bent on achieving a kind

of "technological hegemony". Unless those

two vectors are brought together,

civilization will tend to break down into

incompatible sectors.

- Further

improvements in modern weaponry, even if

under the pretext of strengthening security.

This may result not only in a new spiral of

the arms race and a perilous overabundance

of arms in many States, but also in a final

divorce between the process of disarmament

and development, and, what is more, in an

erosion of the foundations and criteria of

the emerging new world politics.

How can the world community cope with all this?

All these tasks are enormously complex. They

cannot be postponed. Tomorrow may be too late.

I am convinced that in order to solve these

problems there is no other way but to seek and

implement entirely new forms of interaction. We

are simply doomed to such interaction, or we

shall be unable to consolidate positive trends

which have emerged and are gaining strength, and

which we simply must not sacrifice.

However, to accomplish this all members of the

world community should resolutely discard old

stereotypes and motivations nurtured by the Cold

War, and give up the habit of seeking each

other's weak spots and exploiting them in their

own interests. We have to respect the

peculiarities and differences which will always

exist, even when human rights and freedoms are

observed throughout the world. I keep repeating

that with the end of confrontation differences

can be made a source of healthy competition, an

important factor for progress. This is an

incentive to study each other, to engage in

exchanges, a prerequisite for the growth of

mutual trust.

For knowledge and trust are the foundations of a

new world order. Hence the necessity, in my

view, to learn to forecast the course of events

in various regions of the globe, by pooling the

efforts of scientists, philosophers and

humanitarian thinkers within the UN framework.

Policies, even the most prudent and precise, are

made by man. We need maximum insurance to

guarantee that decisions taken by members of the

world community should not affect the security,

sovereignty and vital interests of its other

members or damage the natural environment and

the moral climate of the world.

I am an optimist and I believe that together we

shall be able now to make the right historical

choice so as not to miss the great chance at the

turn of centuries and millennia and make the

current extremely difficult transition to a

peaceful world order. A balance of interests

rather than a balance of power, a search for

compromise and concord rather than a search for

advantages at other people's expense, and

respect for equality rather than claims to

leadership - such are the elements which can

provide the groundwork for world progress and

which should be readily acceptable for

reasonable people informed by the experience of

the twentieth century.

The future prospect of truly peaceful global

politics lies in the creation through joint

efforts of a single international democratic

space in which States shall be guided by the

priority of human rights and welfare for their

own citizens and the promotion of the same

rights and similar welfare elsewhere. This is an

imperative of the growing integrity of the

modern world and of the interdependence of its

components.

I have been suspected of utopian thinking more

than once, and particularly when five years ago

I proposed the elimination of nuclear weapons by

the year 2000 and joint efforts to create a

system of international security. It may well be

that by that date it will not have happened. But

look, merely five years have passed and have we

not actually and noticeably moved in that

direction? Have we not been able to cross the

threshold of mistrust, though mistrust has not

completely disappeared? Has not the political

thinking in the world changed substantially?

Does not most of the world community already

regard weapons of mass destruction as

unacceptable for achieving political objectives?

Ladies and gentlemen, two weeks from today it

will be exactly fifty years since the beginning

of the Nazi invasion of my country. And in

another six months we shall mark fifty years

since Pearl Harbor, after which the war turned

into a global tragedy. [The European war became

World War II in 1941, when Germany invaded the

Soviet Union on June 22 and Japan attacked the

American naval base in Hawaii on December 7.]

Memories of it

still hurt. But they also urge us to value the

chance given to the present generations.

In conclusion, let me say again that I view the

award of the Nobel Prize to me as an expression

of understanding of my intentions, my

aspirations, the objectives of the profound

transformation we have begun in our country, and

the ideas of new thinking. I see it as your

acknowledgment of my commitment to peaceful

means of implementing the objectives of

perestroika.

I am grateful for this to the members of the

Committee and wish to assure them that if I

understand correctly their motives, they are not

mistaken.

More History

|

|