|

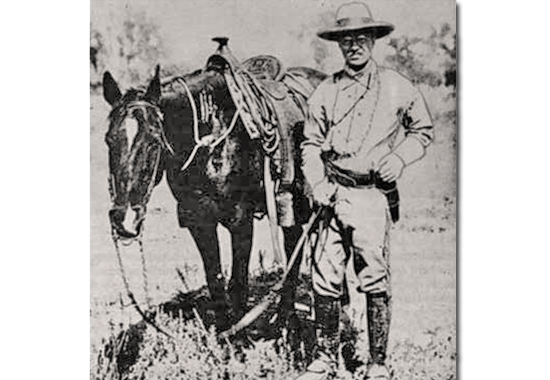

TEDDY ROOSEVELT 1883

The Duties of American Citizenship

It follows the full text transcript of

Theodore Roosevelt's The Duties of American

Citizenship speech, delivered at Buffalo, NY - January

26, 1883.

|

Of course, in one

sense, |

the first

essential for a man's being a good citizen is

his possession of the home virtues of which we

think when we call a man by the emphatic

adjective of manly. No man can be a good citizen

who is not a good husband and a good father, who

is not honest in his dealings with other men and

women, faithful to his friends and fearless in

the presence of his foes, who has not got a

sound heart, a sound mind, and a sound body;

exactly as no amount of attention to civil

duties will save a nation if the domestic life

is undermined, or there is lack of the rude

military virtues which alone can assure a

country's position in the world. In a free

republic the ideal citizen must be one willing

and able to take arms for the defense of the

flag, exactly as the ideal citizen must be the

father of many healthy children. A race must be

strong and vigorous; it must be a race of good

fighters and good breeders, else its wisdom will

come to naught and its virtue be ineffective;

and no sweetness and delicacy, no love for and

appreciation of beauty in art or literature, no

capacity for building up material prosperity can

possibly atone for the lack of the great virile

virtues.

But this is aside from my subject, for what I

wish to talk of is the attitude of the American

citizen in civic life. It ought to be axiomatic

in this country that every man must devote a

reasonable share of his time to doing his duty

in the Political life of the community. No man

has a right to shirk his political duties under

whatever plea of pleasure or business; and while

such shirking may be pardoned in those of small

cleans it is entirely unpardonable in those

among whom it is most common--in the people

whose circumstances give them freedom in the

struggle for life. In so far as the community

grows to think rightly, it will likewise grow to

regard the young man of means who shirks his

duty to the State in time of peace as being only

one degree worse than the man who thus shirks it

in time of war. A great many of our men in

business, or of our young men who are bent on

enjoying life (as they have a perfect right to

do if only they do not sacrifice other things to

enjoyment), rather plume themselves upon being

good citizens if they even vote; yet voting is

the very least of their duties, Nothing worth

gaining is ever gained without effort.

You can no more

have freedom without striving and suffering for

it than you can win success as a banker or a

lawyer without labor and effort, without

self-denial in youth and the display of a ready

and alert intelligence in middle age. The people

who say that they have not time to attend to

politics are simply saying that they are unfit

to live in a free community. Their place is

under a despotism; or if they are content to do

nothing but vote, you can take despotism

tempered by an occasional plebiscite, like that

of the second Napoleon. In one of Lowell's

magnificent stanzas about the Civil War he

speaks of the fact which his countrymen were

then learning, that freedom is not a gift that

tarries long in the hands of cowards: nor yet

does it tarry long in the hands of the sluggard

and the idler, in the hands of the man so much

absorbed in the pursuit of pleasure or in the

pursuit of gain, or so much wrapped up in his

own easy home life as to be unable to take his

part in the rough struggle with his fellow men

for political supremacy. If freedom is worth

having, if the right of self-government is a

valuable right, then the one and the other must

be retained exactly as our forefathers acquired

them, by labor, and especially by labor in

organization, that is in combination with our

fellows who have the same interests and the same

principles.

We should not

accept the excuse of the business man who

attributed his failure to the fact that his

social duties were so pleasant and engrossing

that he had no time left for work in his office;

nor would we pay much heed to his further

statement that he did not like business anyhow

because he thought the morals of the business

community by no means what they should be, and

saw that the great successes were most often won

by men of the Jay Gould stamp. It is just the

same way with politics. It makes one feel half

angry and half amused, and wholly contemptuous,

to find men of high business or social standing

in the community saying that they really have

not got time to go to ward meetings, to organize

political clubs, and to take a personal share in

all the important details of practical politics;

men who further urge against their going the

fact that they think the condition of political

morality low, and are afraid that they may be

required to do what is not right if they go into

politics.

The first duty of an American citizen, then, is

that he shall work in politics; his second duty

is that he shall do that work in a practical

manner; and his third is that it shall be done

in accord with the highest principles of honor

and justice. Of course, it is not possible to

define rigidly just the way in which the work

shall be made practical. Each man's individual

temper and convictions must be taken into

account. To a certain extent his work must be

done in accordance with his individual beliefs

and theories of right and wrong. To a yet

greater extent it must be done in combination

with others, he yielding or modifying certain of

his own theories and beliefs so as to enable him

to stand on a common ground with his fellows,

who have likewise yielded or modified certain of

their theories and beliefs. There is no need of

dogmatizing about independence on the one hand

or party allegiance on the other.

There are

occasions when it may be the highest duty of any

man to act outside of parties and against the

one with which he has himself been hitherto

identified; and there may be many more occasions

when his highest duty is to sacrifice some of

his own cherished opinions for the sake of the

success of the party which he on the whole

believes to be right. I do not think that the

average citizen, at least in one of our great

cities, can very well manage to support his own

party all the time on every issue, local and

otherwise; at any rate if he can do so he has

been more fortunately placed than I have been.

On the other hand,

I am fully convinced that to do the best work

people must be organized; and of course an

organization is really a party, whether it be a

great organization covering the whole nation and

numbering its millions of adherents, or an

association of citizens in a particular

locality, banded together to win a certain

specific victory, as, for instance, that of

municipal reform. Somebody has said that a

racing-yacht, like a good rifle, is a bundle of

incompatibilities; that you must get the utmost

possible sail power without sacrificing some

other quality if you really do get the utmost

sail power, that, in short you have got to make

more or less of a compromise on each in order to

acquire the dozen things needful; but, of

course, in making this compromise you must be

very careful for the sake of something

unimportant not to sacrifice any of the great

principles of successful naval architecture.

Well, it is about

so with a man's political work. He has got to

preserve his independence on the one hand; and

on the other, unless he wishes to be a wholly

ineffective crank, he has got to have some sense

of party allegiance and party responsibility,

and he has got to realize that in any given

exigency it may be a matter of duty to sacrifice

one quality, or it may be a matter of duty to

sacrifice the other.

If it is difficult to lay down any fixed rules

for party action in the abstract; it would, of

course, be wholly impossible to lay them down

for party action in the concrete, with reference

to the organizations of the present day. I think

that we ought to be broad-minded enough to

recognize the fact that a good citizen, striving

with fearlessness, honesty, and common sense to

do his best for the nation, can render service

to it in many different ways, and by connection

with many different organizations. It is well

for a man if he is able conscientiously to feel

that his views on the great questions of the

day, on such questions as the tariff, finance,

immigration, the regulation of the liquor

traffic, and others like them, are such as to

put him in accord with the bulk of those of his

fellow citizens who compose one of the greatest

parties: but it is perfectly supposable that he

may feel so strongly for or against certain

principles held by one party, or certain

principles held by the other, that he is unable

to give his full adherence to either.

In such a case I

feel that he has no right to plead this lack of

agreement with either party as an excuse for

refraining from active political work prior to

election. It will, of course, bar him from the

primaries of the two leading parties, and

preclude him from doing his share in organizing

their management; but, unless he is very

unfortunate, he can surely find a number of men

who are in the same position as himself and who

agree with him on some specific piece of

political work, and they can turn in practically

and effectively long before election to try to

do this new piece of work in a practical manner.

One seemingly very necessary caution to utter

is, that a man who goes into politics should not

expect to reform everything right off, with a

jump. I know many excellent young men who, when

awakened to the fact that they have neglected

their political duties, feel an immediate

impulse to form themselves into an organization

which shall forthwith purify politics

everywhere, national, State, and city alike; and

I know of a man who having gone round once to a

primary, and having, of course, been unable to

accomplish anything in a place where he knew no

one and could not combine with anyone, returned

saying it was quite useless for a good citizen

to try to accomplish anything in such a manner.

To these too hopeful or too easily discouraged

people I always feel like reading Artemus Ward's

article upon the people of his town who came

together in a meeting to resolve that the town

should support the Union and the Civil War, but

were unwilling to take any part in putting down

the rebellion unless they could go as

brigadier-generals.

After the battle

of Bull Run there were a good many hundreds of

thousands of young men in the North who felt it

to be their duty to enter the Northern armies;

but no one of them who possessed much

intelligence expected to take high place at the

outset, or anticipated that individual action

would be of decisive importance in any given

campaign. He went in as private or sergeant,

lieutenant or captain, as the case might be, and

did his duty in his company, in his regiment,

after a while in his brigade. When Ball's Bluff

and Bull Run succeeded the utter failure of the

Peninsular campaign, when the terrible defeat of

Fredericksburg was followed by the scarcely less

disastrous day at Chancellorsville he did not

announce (if he had any pluck or manliness about

him) that he considered it quite useless for any

self-respecting citizen to enter the Army of the

Potomac, because he really was not of much

weight in its councils, and did not approve of

its management; he simply gritted his teeth and

went doggedly on with his duty, grieving over,

but not disheartened at the innumerable

shortcomings and follies committed by those who

helped to guide the destinies of the army,

recognizing also the bravery, the patience,

intelligence, and resolution with which other

men in high places offset the follies and

shortcomings and persevering with equal mind

through triumph and defeat until finally he saw

the tide of failure turn at Gettysburg and the

full flood of victory come with Appomattox.

I do wish that more of our good citizens would

go into politics, and would do it in the same

spirit with which their fathers went into the

Federal armies. Begin with the little thing, and

do not expect to accomplish anything without an

effort. Of course, if you go to a primary just

once, never having taken the trouble to know any

of the other people who go there you will find

yourself wholly out of place; but if you keep on

attending and try to form associations with

other men whom you meet at the political

gatherings, or whom you can persuade to attend

them, you will very soon find yourself a weight.

In the same way,

if a man feels that the politics of his city,

for instance, are very corrupt and wants to

reform them, it would be an excellent idea for

him to begin with his district. If he Joins with

other people, who think as he does, to form a

club where abstract political virtue will be

discussed he may do a great deal of good. We

need such clubs; but he must also get to know

his own ward or his own district, put himself in

communication with the decent people in that

district, of whom we may rest assured there will

be many, willing and able to do something

practical for the procurance of better

government Let him set to work to procure a

better assemblyman or better alderman before he

tries his hand at making a mayor, a governor, or

a president. If he begins at the top he may make

a brilliant temporary success, but the chances

are a thousand to one that he will only be

defeated eventually; and in no event will the

good he does stand on the same broad and

permanent foundation as if he had begun at the

bottom.

Of course, one or

two of his efforts may be failures; but if he

has the right stuff in him he will go ahead and

do his duty irrespective of whether he meets

with success or defeat. It is perfectly right to

consider the question of failure while shaping

one's efforts to succeed in the struggle for the

right; but there should be no consideration of

it whatsoever when the question is as to whether

one should or should not make a struggle for the

right. When once a band of one hundred and fifty

or two hundred honest, intelligent men, who mean

business and know their business, is found in

any district, whether in one of the regular

organizations or outside, you can guarantee that

the local politicians of that district will

begin to treat it with a combination of fear,

hatred, and respect, and that its influence will

be felt; and that while sometimes men will be

elected to office in direct defiance of its

wishes, more often the successful candidates

will feel that they have to pay some regard to

its demands for public decency and honesty.

But in advising you to be practical and to work

hard, I must not for one moment be understood as

advising you to abandon one iota of your

self-respect and devotion to principle. It is a

bad sign for the country to see one class of our

citizens sneer at practical politicians, and

another at Sunday-school politics. No man can do

both effective and decent work in public life

unless he is a practical politician on the one

hand, and a sturdy believer in Sunday-school

politics on the other. He must always strive

manfully for the best, and yet, like Abraham

Lincoln, must often resign himself to accept the

best possible.

Of course when a

man verges on to the higher ground of

statesmanship, when he becomes a leader, he must

very often consult with others and defer to

their opinion, and must be continually settling

in his mind how far he can go in just deference

to the wishes and prejudices of others while yet

adhering to his own moral standards: but I speak

not so much of men of this stamp as I do of the

ordinary citizen, who wants to do his duty as a

member of the commonwealth in its civic life;

and for this man I feel that the one quality

which he ought always to hold most essential is

that of disinterestedness. If he once begins to

feel that he wants office himself, with a

willingness to get it at the cost of his

convictions, or to keep it when gotten, at the

cost of his convictions, his usefulness is gone.

Let him make up his mind to do his duty in

politics without regard to holding office at

all, and let him know that often the men in this

country who have done the best work for our

public life have not been the men in office.

If, on the other

hand, he attains public position, let him not

strive to plan out for himself a career. I do

not think that any man should let himself regard

his political career as a means of livelihood,

or as his sole occupation in life; for if he

does he immediately becomes most seriously

handicapped. The moment that he begins to think

how such and such an act will affect the voters

in his district, or will affect some great

political leader who will have an influence over

his destiny, he is hampered and his hands are

bound. Not only may it be his duty often to

disregard the wishes of politicians, but it may

be his clear duty at times to disregard the

wishes of the people. The voice of the people is

not always the voice of God; and when it happens

to be the voice of the devil, then it is a man's

clear duty to defy its behests. Different

political conditions breed different dangers.

The demagogue is as unlovely a creature as the

courtier, though one is fostered under

republican and the other under monarchical

institutions.

There is every

reason why a man should have an honorable

ambition to enter public life, and an honorable

ambition to stay there when he is in; but he

ought to make up his mind that he cares for it

only as long as he can stay in it on his own

terms, without sacrifice of his own principles;

and if he does thus make up his mind he can

really accomplish twice as much for the nation,

and can reflect a hundredfold greater honor upon

himself, in a short term of service, than can

the man who grows gray in the public employment

at the cost of sacrificing what he believes to

be true and honest. And moreover, when a public

servant has definitely made up his mind that he

will pay no heed to his own future, but will do

what he honestly deems best for the community,

without regard to how his actions may affect his

prospects, not only does he become infinitely

more useful as a public servant, but he has a

far better time. He is freed from the harassing

care which is inevitably the portion of him who

is trying to shape his sails to catch every gust

of the wind of political favor.

But let me reiterate, that in being virtuous he

must not become ineffective, and that he must

not excuse himself for shirking his duties by

any false plea that he cannot do his duties and

retain his self-respect. This is nonsense, he

can; and when he urges such a plea it is a mark

of mere laziness and self-indulgence. And again,

he should beware how he becomes a critic of the

actions of others, rather than a doer of deeds

himself; and in so far as he does act as a

critic (and of course the critic has a great and

necessary function) he must beware of

indiscriminate censure even more than of

indiscriminate praise.

The screaming

vulgarity of the foolish spread-eagle orator who

is continually yelling defiance at Europe,

praising everything American, good and bad, and

resenting the introduction of any reform because

it has previously been tried successfully

abroad, is offensive and contemptible to the

last degree; but after all it is scarcely as

harmful as the peevish, fretful, sneering, and

continual faultfinding of the refined,

well-educated man, who is always attacking good

and bad alike, who genuinely distrusts America,

and in the true spirit of servile colonialism

considers us inferior to the people across the

water. It may be taken for granted that the man

who is always sneering at our public life and

our public men is a thoroughly bad citizen, and

that what little influence he wields in the

community is wielded for evil. The public

speaker or the editorial writer who teaches men

of education that their proper attitude toward

American politics should be one of dislike or

indifference is doing all he can to perpetuate

and aggravate the very evils of which he is

ostensibly complaining.

Exactly as it is

generally the case that when a man bewails the

decadence of our civilization he is himself

physically, mentally, and morally a first-class

type of the decadent, so it is usually the case

that when a man is perpetually sneering at

American politicians, whether worthy or

unworthy, he himself is a poor citizen and a

friend of the very forces of evil against which

he professes to contend. Too often these men

seem to care less for attacking bad men, than

for ruining the characters of good men with whom

they disagree on some pubic question; and while

their influence against the bad is almost nil,

they are sometimes able to weaken the hands of

the good by withdrawing from them support to

which they are entitled, and they thus count in

the sum total of forces that work for evil. They

answer to the political prohibitionist, who, in

a close contest between a temperance man and a

liquor seller diverts enough votes from the

former to elect the liquor seller Occasionally

it is necessary to beat a pretty good man, who

is not quite good enough, even at the cost of

electing a bad one- but it should be thoroughly

recognized that this can be necessary only

occasionally and indeed, I may say, only in very

exceptional cases, and that as a rule where it

is done the effect is thoroughly unwholesome in

every way, and those taking part in it deserve

the severest censure from all honest men.

Moreover, the very need of denouncing evil makes

it all the more wicked to weaken the effect of

such denunciations by denouncing also the good.

It is the duty of all citizens, irrespective of

party, to denounce, and, so far as may be, to

punish crimes against the public on the part of

politicians or officials. But exactly as the

public man who commits a crime against the

public is one of the worst of criminals, so,

close on his heels in the race for iniquitous

distinction, comes the man who falsely charges

the public servant with outrageous wrongdoing;

whether it is done with foul-mouthed and foolish

directness in the vulgar and violent party

organ, or with sarcasm, innuendo, and the

half-truths that are worse than lies, in some

professed organ of independence.

Not only should

criticism be honest, but it should be

intelligent, in order to be effective. I

recently read in a religious paper an article

railing at the corruption of our public life, in

which it stated incidentally that the lobby was

recognized as all-powerful in Washington. This

is untrue. There was a day when the lobby was

very important at Washington, but its influence

in Congress is now very small indeed; and from a

pretty intimate acquaintance with several

Congresses I am entirely satisfied that there is

among the members a very small proportion indeed

who are corruptible, in the sense that they will

let their action be influenced by money or its

equivalent. Congressmen are very often

demagogues; they are very often blind partisans;

they are often exceedingly short-sighted,

narrow-minded, and bigoted; but they are not

usually corrupt; and to accuse a narrow-minded

demagogue of corruption when he is perfectly

honest, is merely to set him more firmly in his

evil course and to help him with his

constituents, who recognize that the charge is

entirely unjust, and in repelling it lose sight

of the man's real shortcomings.

I have known more

than one State legislature, more than one board

of aldermen against which the charge of

corruption could perfectly legitimately be

brought, but it cannot be brought against

Congress. Moreover these sweeping charges really

do very little good. When I was in the New York

legislature, one of the things that I used to

mind most was the fact that at the close of

every session the papers that affect morality

invariably said that particular legislature was

the worst legislature since the days of Tweed.

The statement was not true as a rule; and, in

any event, to lump all the members, good and

bad, in sweeping condemnation simply hurt the

good and helped the bad. Criticism should be

fearless, but I again reiterate that it should

be honest and should be discriminating. When it

is sweeping and unintelligent, and directed

against good and bad alike, or against the good

and bad qualities of any man alike, it is very

harmful. It tends steadily to deteriorate the

character of our public men; and it tends to

produce a very unwholesome spirit among young

men of education, and especially among the young

men in our colleges.

Against nothing is fearless and specific

criticism more urgently needed than against the

"spoils system," which is the degradation of

American politics. And nothing is more effective

in thwarting the purposes of the spoilsmen than

the civil service reform. To be sure, practical

politicians sneer at it. One of them even went

so far as to say that civil-service reform is

asking a man irrelevant questions. What more

irrelevant question could there be than that of

the practical politician who asks the aspirant

for his political favor - "Whom did you vote for

in the last election?" There is certainly

nothing more interesting, from a humorous point

of view, than the heads of departments urging

changes to be made in their underlings, "on the

score of increased efficiency" they say; when as

the result of such a change the old incumbent

often spends six months teaching the new

incumbent how to do the work almost as well as

he did himself!

Occasionally the

civil-service reform has been abused, but not

often. Certainly the reform is needed when you

contemplate the spectacle of a New York City

treasurer who acknowledges his annual fees to be

eighty-five thousand dollars, and who pays a

deputy one thousand five hundred dollars to do

his work-when you note the corruptions in the

New York legislature, where one man says he has

a horror of the Constitution because it prevents

active benevolence, and another says that you

should never allow the Constitution to come

between friends! All these corruptions and vices

are what every good American citizen must fight

against.

Finally, the man who wishes to do his duty as a

citizen in our country must be imbued through

and through with the spirit of Americanism. I am

not saying this as a matter of spread-eagle

rhetoric: I am saying it quite soberly as a

piece of matter-of-fact, common-sense advice,

derived from my own experience of others. Of

course, the question of Americanism has several

sides. If a man is an educated man, he must show

his Americanism by not getting misled into

following out and trying to apply all the

theories of the political thinkers of other

countries, such as Germany and France, to our

own entirely different conditions. He must not

get a fad, for instance, about responsible

government; and above all things he must not,

merely because he is intelligent, or a college

professor well read in political literature, try

to discuss our institutions when he has had no

practical knowledge of how they are worked.

Again, if he is a

wealthy man, a man of means and standing, he

must really feel, not merely affect to feel,

that no social differences obtain save such as a

man can in some way himself make by his own

actions. People sometimes ask me if there is not

a prejudice against a man of wealth and

education in ward politics. I do not think that

there is, unless the man in turn shows that he

regards the facts of his having wealth and

education as giving him a claim to superiority

aside from the merit he is able to prove himself

to have in actual service. Of course, if he

feels that he ought to have a little better

treatment than a carpenter, a plumber, or a

butcher, who happens to stand beside him, he is

going to be thrown out of the race very quickly,

and probably quite roughly; and if he starts in

to patronize and elaborately condescend to these

men he will find that they resent this attitude

even more. Do not let him think about the matter

at all.

Let him go into

the political contest with no more thought of

such matters than a college boy gives to the

social standing of the members of his own and

rival teams in a hotly contested football match.

As soon as he begins to take an interest in

politics (and he will speedily not only get

interested for the sake of politics, but also

take a good healthy interest in playing the game

itself - an interest which is perfectly normal

and praise-worthy, and to which only a prig

would object), he will begin to work up the

organization in the way that will be most

effective, and he won't care a rap about who is

put to work with him, save in so far as he is a

good fellow and an efficient worker. There was

one time that a number of men who think as we do

here to-night (one of the number being myself)

got hold of one of the assembly districts of New

York, and ran it in really an ideal way, better

than any other assembly district has ever been

run before or since by either party.

We did it by hard

work and good organization; by working

practically, and yet by being honest and square

in motive and method: especially did we do it by

all turning in as straight-out Americans without

any regard to distinctions of race origin. Among

the many men who did a great deal in organizing

our victories was the son of a Presbyterian

clergyman, the nephew of a Hebrew rabbi, and two

well-known Catholic gentlemen. We also had a

Columbia College professor (the stroke-oar of a

university crew), a noted retail butcher, and

the editor of a local German paper, various

brokers, bankers, lawyers, bricklayers and a

stone-mason who was particularly useful to us,

although on questions of theoretic rather than

applied politics he had a decidedly socialistic

turn of mind.

Again, questions of race origin, like questions

of creed, must not be considered: we wish to do

good work, and we are all Americans, pure and

simple. In the New York legislature, when it

fell to my lot to choose a committee - which I

always esteemed my most important duty at Albany

- no less than three out of the four men I chose

were of Irish birth or parentage; and three

abler and more fearless and disinterested men

never sat in a legislative body; while among my

especial political and personal friends in that

body was a gentleman from the southern tier of

counties, who was, I incidentally found out, a

German by birth, but who was just as straight

United States as if his ancestors had come over

here in the Mayflower or in Henry Hudson's

yacht.

Of course, none of

these men of Irish or German birth would have

been worth their salt had they continued to act

after coming here as Irishmen or Germans, or as

anything but plain straight-out Americans. We

have not any room here for a divided allegiance.

A man has got to be an American and nothing

else; and he has no business to be mixing us up

with questions of foreign politics, British or

Irish, German or French, and no business to try

to perpetuate their language and customs in the

land of complete religious toleration and

equality. If, however, he does become honestly

and in good faith an American, then he is

entitled to stand precisely as all other

Americans stand, and it is the height of

un-Americanism to discriminate against him in

any way because of creed or birthplace. No

spirit can be more thoroughly alien to American

institutions, than the spirit of the

Know-Nothings.

In facing the future and in striving, each

according to the measure of his individual

capacity, to work out the salvation of our land,

we should be neither timid pessimists nor

foolish optimists. We should recognize the

dangers that exist and that threaten us: we

should neither overestimate them nor shrink from

them, but steadily fronting them should set to

work to overcome and beat them down. Grave

perils are yet to be encountered in the stormy

course of the Republic - perils from political

corruption, perils from individual laziness,

indolence and timidity, perils springing from

the greed of the unscrupulous rich, and from the

anarchic violence of the thriftless and

turbulent poor. There is every reason why we

should recognize them, but there is no reason

why we should fear them or doubt our capacity to

overcome them, if only each will, according to

the measure of his ability, do his full duty,

and endeavor so to live as to deserve the high

praise of being called a good American citizen.

More History

|

|