|

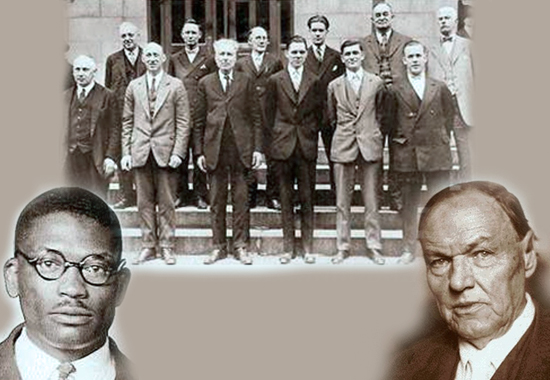

HENRY SWEET, JURY, CLARENCE DARROW -

MICHIGAN VS. SWEET 1926

The Law of Love - Page 2

|

|

Go here for more about

Clarence Darrow. Clarence Darrow.

Go here for more about

Darrow's Law of Love speech. Darrow's Law of Love speech.

It follows the full text transcript of

Clarence Darrow's closing argument in the case

The People of Michigan vs. Henry Sweet, delivered at

Detroit, Michigan - May 11, 1926. |

This is page 2 of 2. Go to

page 1.

page 1.

|

[Lunch Break] |

I was speaking before luncheon about the people

around the house, and the wonderful protection

the blacks had. Nobody can tell exactly how many

were there, of course. Here is a man, a real

estate dealer, who had an office at the corner

of St. Clair and Charlevoix, just a block away.

He came down that night,--he was in the habit of

staying at his office, and he had a partner.

Real estate men are pretty wary people, you

know. They don't miss many chances. If there is

anybody around that looks like a prospect, they

are on hand. He came down and saw that crowd.

What did he do? He went over to this

apartment-building on the corner. He stuck

around the apartment-building ten or fifteen

minutes or half an hour, I don't know just how

long, and he leaves his office open. He stuck

around ten or fifteen minutes and then went back

to his office; not to make a sale, but to get

his partner, who was the only man in charge of

the office. And so the two of them started back

and stood there on the corner until the shooting

began.

What do you suppose they were there for? Real

estate men don't waste time with a crowd around

the office. Not only was he content and brought

his partner, and left nobody in the office. He

didn't even stop to lock the door, and they

stayed there on the corner until the shooting

began.

Witnesses forget

themselves and tell the truth. Why were the

police telling people to move on? All the

witnesses said they were not permitted to stand

near the house. Why do they, every once in a

while, pull themselves up and say that the crowd

was so and so? Why does the little boy come into

this court room and on the first trial of this

case say: "I saw a large crowd," and then pull

himself up; "I saw a great many people," and

then say, "I saw a few?" And then on

cross-examination admit that he had been told to

do it, and had forgot himself when he said a

great many people? This is in the record as

coming from the last case, and he said it was

true. It was true, and every man in this case

who has listened to it knows that it is true.

Oh, they say, there is nothing to justify this

shooting; it was an orderly, neighborly crowd;

an orderly, neighborly crowd. They came there

for a purpose and intended to carry it out. How

long, pray, would these men wait penned up in

that house? How long would you wait? The very

presence of the crowd was a mob, as I believe

the Court will tell you.

Suppose a crowd

gathers around your house; a crowd which doesn't

want you there; a hostile crowd, for a part of

two days and two nights, until the police force

of the city is called in to protect you. How

long, tell me, are you going to live in that

condition with a mob surrounding your house and

the police-force standing in front of it? How

long should these men have waited? I can imagine

why they waited as long as they did. You

wouldn't have waited. Counsel say they had just

as good reason to shoot on the 8th as on the

9th. Concede it. They did not shoot. They waited

and hoped and prayed that in some way this crowd

would pass them by and grant them the right to

live.

The mob came back

the next night and the colored people waited

while they were gathering; they waited while

they were coming from every street and every

corner, and while the officers were supine and

helpless and doing nothing. And they waited

until dozens of stones were thrown against the

house on the roof, probably-- don't know how

many. Nobody knows how many. They waited until

the windows were broken before they shot. Why

did they wait so long? I think I know. How much

chance had these people for their life after

they shot; surrounded by a crowd, as they were?

They would never take a chance unless they

thought it was necessary to take the chance.

Eleven black people penned up in the face of a

mob. What chance did they have?

Suppose they shot before they should. What is

the theory of counsel in this case? Nobody

pretends there is anything in this case to prove

that our client Henry fired the fatal shot.

There isn't the slightest. It wasn't a shot that

would fit the gun he had. The theory of this

case is that he was a part of a combination to

do something. Now, what was that combination,

gentlemen? Your own sense will tell you what it

was. Did they combine to go there and kill

somebody? Were they looking for somebody to

murder?

Dr. Sweet scraped

together his small earnings by his industry and

put himself through college, and he scraped

together his small earnings of three thousand

dollars to buy that home because he wanted to

kill somebody? It is silly to talk about it. He

bought that home just as you buy yours, because

he wanted a home to live in, to take his wife

and to raise his family. There is no difference

between the love of a black man for his

offspring and the love of a white. He and his

wife had the same feeling of fatherly and

motherly affection for their child that you

gentlemen have for yours, and that your father

and mother had for you. They bought that home

for that purpose; not to kill some body.

They might have

feared trouble, as they probably did, and as the

evidence shows that every man with a black face

fears it, when he moved into a home that is fit

for a dog to live in. It is part of the curse

that, for some inscrutable reason, has followed

the race--if you call it a race--and which

curse, let us hope, sometime the world will be

wise enough and decent enough and human enough

to wipe out.

They went there to live. They knew the dangers.

Why do you suppose they took these guns and this

ammunition and these men there? Because they

wanted to kill somebody? It is utterly absurd

and crazy. They took them there because they

thought it might be necessary to defend their

home with their lives and they were determined

to do it. They took guns there that in case of

need they might fight, fight even to death for

their home, and for each other, for their

people, for their race, for their rights under

the Constitution and the laws under which all of

us live; and unless men and women will do that,

we will soon be a race of slaves, whether we are

black or white. "Eternal vigilance is the price

of liberty," and it has always been so and

always will be. Do you suppose they were in

there for any other purpose? Gentlemen, there

isn't a chance that they took arms there for

anything else.

They did go there

knowing their rights, feeling their

responsibility, and determined to maintain those

rights if it meant death to the last man and the

last woman, and no one could do more. No man

lived a better life or died a better death than

fighting for his home and his children, for

himself, and for the eternal principles upon

which life depends. Instead of being here under

indictment, for murder, they should be honored

for the brave stand they made, for their rights

and ours. Some day, both white and black,

irrespective of color, will honor the memory of

these men, whether they are inside prison-walls

or outside, and will recognize that they fought

not only for themselves, but for every man who

wishes to be free.

Did they shoot too quick? Tell me just how long

a man needs wait for a mob? The Court, I know,

will instruct you on that. How long do you need

to wait for a mob?

We have been told that because a person

trespasses on your home or on your ground you

have no right to shoot him. Is that true? If I

go up to your home in a peaceable way, and go on

your ground, or on your porch, you have no right

to shoot me. You have a right to use force to

put me off if I refuse to go, even to the extent

of killing me. That isn't this case, gentlemen.

That isn't the case of a neighbor who went up to

the yard of a neighbor without permission and

was shot to death. Oh, no. The Court will tell

you the difference, unless I am mistaken, and I

am sure I am not; unless I mistake the law, and

I am sure, I do not.

This isn't a case

of a man who trespasses upon the ground of some

other man and is killed. It is the case of an

unlawful mob, which in itself is a crime; a mob

bent on mischief; a mob that has no rights. They

are too dangerous. It is like a fire. One man

may do something. Two will do a much more; three

will do more than three times as much; a crowd

will do something that no man ever dreamed of

doing. The law recognizes it. It is the duty of

every man, I don't care who he is, to disperse a

mob. It is the duty of the officers to disperse

them. It was the duty of the inmates of the

house, even though they had to kill somebody to

do it. Now, gentlemen, I wouldn't ask you to

take the law on my statement. The Court will

tell you the law. A mob is a criminal

combination of itself. Their presence is enough.

You need not wait until it spreads. It is there,

and that is enough. There is no other law; there

hasn't been for years, and it is the law which

will govern this case.

Now, gentlemen,

how long did they need to wait? Why, it is

silly. How long would you wait? How long do you

suppose ten white men would be waiting? Would

they have waited as long? I will tell you how

long they needed to wait. I will tell you what

the law is, and the Court will confirm me, I am

sure. Every man may act upon appearances as they

seem to him. Every man may protect his own life.

Every man has the right to protect his own

property. Every man is bound under the law to

disperse a mob even to the extent of taking

life. It is his duty to do it, but back of that

he has the human right to go to the extent of

killing to defend his life. He has a right to

defend the life of his kinsman, servant, his

friends, or those about him, and he has a right

to defend, gentlemen, not from real danger, but

from what seems to him real danger at the time.

Here is Henry

Sweet, the defendant in this case, a boy. How

many of you know why you are trying him? What

had he to do with it? Why is he in this case? A

boy, twenty-one years old, working his way

through college, and he is just as good a boy as

the boy of any juror in this box; just as good a

boy as you people were when you were boys, and I

submit to you, he did nothing whatever that was

wrong.

Of course, we

lawyers talk and talk and talk, as if we feared

results. I don't mean to trifle with you. I

always fear results. When life or liberty is in

the hands of a lawyer, he realizes the terrible

responsibility that is on him, and he fears that

some word will be left unspoken, or some thought

will be forgotten. I would not be telling you

the truth if I told you that I did not fear the

result of this important case; and when my

judgment and my reason comes to my aid and takes

counsel with my fears, I know, and I feel

perfectly well that no twelve American jurors,

especially in any northern land, could be

brought together who would dream of taking a

boy's life or liberty under circumstances like

this. That is what my judgment tells me, but my

fears perhaps cause me to go further and to say

more when I should not have said as much.

Now, let me tell you when a man has the right to

shoot in self-defense, and in defense of his

home; not when these vital things in life are in

danger, but when he thinks they are. These

despised blacks did not need to wait until the

house was beaten down above their heads. They

didn't need to wait until every window was

broken. They didn't need to wait longer for that

mob to grow more inflamed. There is nothing so

dangerous as ignorance and bigotry when it is

unleashed as it was here. The Court will tell

you that these inmates of this house had the

right to decide upon appearances, and if they

did, even though they were mistaken they are not

guilty. I don't know but they could safely have

stayed a little longer. I don't know but it

would have been well enough to let this mob

break a few more window-panes. I don't know but

it would have been better and been safe to have

let them batter down the house before they shot.

I don't know.

How am I to tell,

and how are you to tell? You are twelve white

men, gentlemen. You are twelve men sitting here

eight months after all this occurred, listening

to the evidence, perjured and otherwise, in this

court, to tell whether they acted too quickly or

too slowly. A man may be running an engine out

on the railroad. He may stop too quickly or too

slowly. In an emergency he is bound to do one or

the other, and the jury a year after, sitting in

cold blood, may listen to the evidence and say

that he acted too quickly. What do they know

about it? You must sit out there upon a moving

engine with your hand on the throttle and facing

danger and must decide and act quickly. Then you

can tell.

Cases often occur

in the courts, which doesn't speak very well for

the decency of courts, but they have happened,

where men have been shipwrecked at sea, a number

of the men having left the ship and gone into a

small boat to save their lives; they have

floated around for hours and tossed on the wild

waves of an angry sea; their food disappearing,

the boat heavy and likely to sink and no

friendly sail in sight,--What are they to do?

Will they throw some of their companions off the

boat and save the rest? Will they eat some to

save the others? If they kill anybody, it is

because they want to live. Every living thing

wants to live. The strongest instinct in life is

to keep going. You have seen a tree upon a rock

send a shoot down for ten or fifteen or twenty

feet, to search for water, to draw it up, that

it may still survive; it is a strong instinct

with animals and with plants, with all sentient

things, to keep alive.

Men are out in a

boat, in an angry sea, with little food, and

less water. No hope in sight. What will they do?

They throw a companion overboard to save

themselves, or they kill somebody to save

themselves. Juries have come into court and

passed on the question of whether they should

have waited longer, or not. Later, the survivors

were picked up by a ship and perhaps, if they

had waited longer, all would have been saved;

yet a jury, months after it was over, sitting

safely in their jury-box, pass upon the question

of whether they acted too quickly or not.

Can they tell? No. To decide that case, you must

be in a small boat, with little food and water;

in a wild sea, with no sail in sight, and

drifting around for hours or days in the face of

the deep, beset by hunger and darkness and fear

and hope. Then you can tell; but, no man can

tell without it. It can't be done, gentlemen,

and the law says so, and this Court will tell

you so.

Let me tell you

what you must do, gentlemen. It is fine for

lawyers to say, naively, that nothing happened.

No foot was set upon that ground; as if you had

to put your foot on the premises. You might put

your hand on. The foot isn't sacred. No foot was

set upon their home. No shot was fired, nothing

except that the house was stoned and windows

broken; and an angry crowd was outside seeking

their destruction. That is all. That is all,

gentlemen. I say that no American citizen,

unless he is black, need wait until an angry mob

sets foot upon his premises before he kills. I

say that no free man need wait to see just how

far an aggressor will go before he takes life.

The first instinct

a man has is to save his life. He doesn't need

to experiment. He hasn't time to experiment.

When he thinks it is time to save his life, he

has the right to act. There isn't any question

about it. It has been the law of every English

speaking country so long as we have had law.

Every man's home is his castle, which even the

King may not enter. Every man has a right to

kill to defend himself or his family, or others,

either in the defense of the home or in the

defense of themselves.

So far as that

branch of the case is concerned, there is only

one thing that this jury has a right to

consider, and that is whether the defendants

acted in honest fear of danger. That is all.

Perhaps they could have safely waited longer. I

know a little about psychology. If I could talk

to a man long enough, and not too long, and he

talk to me a little, I could guess fairly well

what is going on in his head, but I can't

understand the psychology of a mob, and neither

can anybody else. We know it is unreasoning. We

know it is filled with hatred. We know it is

cruel. We know it has no heart, no soul, and no

pity. We know it is as cruel as the grave. No

man has a right to stop and dicker while waiting

for a mob.

Now, let us look at these fellows. Here were

eleven colored men, penned up in the house. Put

yourselves in their place. Make yourselves

colored for a little while. It won't hurt, you

can wash it off. They can't, but you can; just

make yourself black men for a little while; long

enough, gentlemen, to judge them, and before any

of you would want to be judged, you would want

your juror to put himself in your place. That is

all I ask in this case, gentlemen. They were

black, and they knew the history of the black.

Our friend makes

fun of Dr. Sweet and Henry Sweet talking these

things all over in the short space of two

months. Well, gentlemen, let me tell you

something, that isn't evidence. This is just

theory. This is just theory, and nothing else. I

should imagine that the only thing that two or

three colored people talk of when they get

together is race. I imagine that they can't rub

color off their face or rub it out of their

minds. I imagine that is it with them always. I

imagine that the stories of lynchings, the

stories of murders, the stories of oppression is

a topic of constant conversation. I imagine that

everything that appears in the newspapers on

this subject is carried from one to another

until every man knows what others know, upon the

topic which is the most important of all to

their lives.

What do you think

about it? Suppose you were black. Do you think

you would forget it even in your dreams? Or

would you have black dreams? Suppose you had to

watch every point of contact with your neighbor

and remember your color, and you knew your

children were growing up under this handicap. Do

you suppose you would think of anything else?

Well, gentlemen, I

imagine that a colored man would think of that

before he would think of where he could get

bootleg whiskey, even. Do you suppose this boy

coming in here didn't know all about the

conditions, and did not learn all about them?

Did he not know about Detroit? Do you suppose he

hadn't read the story of his race? He is

intelligent. He goes to school. He would have

been a graduate now, except for this long

hesitation, when he is waiting to see whether he

goes back to college or goes to jail. Do you

suppose that black students and teachers are

discussing it?

Anyhow, gentlemen, what is the use? The jury

isn't supposed to be entirely ignorant. They are

supposed to know something. These black people

were in the house with the black man's

psychology, and with the black man's fear,

based, on what they had heard and what they had

read and what they knew. I don't need to go far.

I don't need to travel to Florida. I don't even

need to talk about the Chicago riots. The

testimony showed that in Chicago a colored boy

on a raft had been washed to a white bathing

beach, and men and boys of my race stoned him to

death. A riot began, and some hundred and twenty

were killed.

I don't need to go

to Washington or to St. Louis. Let us take

Detroit. I don't need to go far either in space

or time. Let us take this city. Now, gentlemen,

I am not saying that the white people of Detroit

are different from the white people of any other

city. I know what has been done in Chicago. I

know what prejudice growing out of race and

religion has done the world over, and all

through time. I am not blaming Detroit. I am

stating what has happened, that is all. And I

appeal to you, gentlemen, to do your part to

save the honor of this city, to save its

reputation, to save yours, to save its name, and

to save the poor colored people who can not save

themselves.

I was told there

had not been a lynching of a colored man in

thirty years or more in Michigan. All right.

Why, I can remember when the early statesmen of

Michigan cared for the colored man and when they

embodied the rights of the colored men in the

constitution and statutes. I can remember when

they laid the foundation that made it possible

for a man of any color or any religion, or any

creed, to own his home wherever he could find a

man to sell it. I remember when civil rights

laws were passed that gave the Negro the right

to go where the white man went and as he went.

There are some men who seem to think those laws

were wrong. I do not. Wrong or not, it is the

law, and if you were black you would protest

with every fiber of your body your right to

live.

Michigan used to

protect the rights of colored people. There were

not many of them here, but they have come in the

last few years, and with them has come

prejudice. Then, too, the southern white man has

followed his black slave. But that isn't all.

Black labor has come in competition with white.

Prejudices have been created where there was no

prejudice before. We have listened to the siren

song that we are a superior race and have

superior rights, and that the black man has

none.

It is a new idea

in Detroit that a colored man's home can be torn

down about his head because he is black. There

are some eighty thousand blacks here now, and

they are bound to reach out. They have reached

out in the past, and they will reach out in the

future. Do not make any mistake, gentlemen. I am

making no promises. I know the instinct for

life. I know it reaches black and white alike. I

know that you can not confine any body of people

to any particular place, and, as the population

grows, the colored people will go farther. I

know it, and you must change the law or you must

take it as it is, or you must invoke the primal

law of nature and get back to clubs and fists,

and if you are ready for that, gentlemen, all

right, but do it with your eyes open. That is

all I care for. You must have a government of

law or blind force, and if you are ready to let

blind force take the place of law, the

responsibility is on you, not on me.

Now, let us see

what has happened here. So far as I know, there

had been nothing of the sort happened when Dr.

Sweet bought his home. He took an option on it

in May, and got his deed in June; and in July,

in that one month, while he was deliberating on

moving, there were three cases of driving Negro

families out of their homes in Detroit. This was

accomplished by stones, clubs, guns and mobs.

Suppose one of you were colored and had bought a

house on Garland Avenue. Take this just exactly

as it is. You bought it in June, intending to

move in July, and you read and heard about what

happened to Dr. Turner in another part of the

city. Would you have waited? Would you have

waited a month, as Sweet did? Suppose you had

heard of what happened to Bristol? Would you

have waited? Remember, these men didn't have any

too much money. Dr. Sweet paid three thousand

dollars on his home, leaving a loan on it of

sixteen thousand dollars more. He had to scrape

together some money to buy his furniture, and he

bought fourteen hundred dollars worth the day

after he moved in and paid two hundred dollars

down.

Gentlemen, it is

only right to consider Dr. Sweet and his family.

He has a little child. He has a wife. They must

live somewhere. If they could not, it would be

better to take them out and kill them, and kill

them decently and quickly. Had he any right to

be free?

They determined to

move in and to take nine men with them. What

would you have done, gentlemen? If you had

courage, you would have done as Dr. Sweet did.

You would have been crazy or a coward if you

hadn't. Would you have moved in alone? No, you

would not have gone alone. You would have taken

your wife. If you had a brother or two, you

would have taken them because you would know,

that you could rely on them, and you would have

taken those nearest to you. And you would have

moved in just as Dr. Sweet did. Wouldn't you? He

didn't shoot the first night. He didn't look for

trouble. He kept his house dark so that the

neighbors wouldn't see him. He didn't dare have

a light in his house, gentlemen, for fear of the

neighbors. Noble neighbors, who were to have a

colored family in their neighborhood. He had the

light put out in the front part of the house, so

as not to tempt any of the mob to violence.

Now, let us go

back a little. What happened before this? I

don't need to go over the history of the case.

Everybody who wants to understand knows it, and

many who don't want to understand it. As soon as

Dr. Sweet bought this house, the neighbors

organized the "Water Works Park Improvement

Association." They made a constitution and

by-laws. You may read the constitution and

by-laws of every club, whether it is the Rotary

Club or the--I was trying to think of some other

club, but I can't. Whatever the club, it must

always have a constitution and by-laws. These

are all about the same. You cannot tell anything

about a man by the church he belongs to. You

can't tell anything about him by the kind of

clothes he wears. You can't tell anything about

him by any of these extraneous matters, and you

can't tell anything about an association from

the by-laws. Not a thing. I belonged to

associations in my time. As far as I can

remember, they all had by-laws.

Mr. Toms: All of

them have the same by-laws?

Mr. Darrow: Yes,

all have the same. They are all of them engaged

in the work of uplifting humanity, and humanity

still wants to stay down. All engaged in the

same work, according to their by-laws,

gentlemen. So, the "Water Works Park Improvement

Club" had by-laws. They were going to aid the

police. They didn't get a chance to try to aid

them until that night. They were going to

regulate automobile traffic. They didn't get any

chance to regulate automobile traffic until that

night. They were going to protect the homes and

make them safe for children.

The purpose was

clear, and every single member reluctantly said

that they joined it to keep colored people out

of the district. They might have said it first

as well as last. People, even in a wealthy and

aristocratic neighborhood like Garland and

Charlevoix, don't give up a dollar without

expecting some profit; not a whole dollar.

Sometimes two in one family, the husband and

wife, joined.

They got in quick. The woods were on fire.

Something had to be done, as quick as they heard

that Dr. Sweet was coming; Dr. Sweet, who had

been a bellhop on a boat, and a bellhop in

hotels, and fired furnaces and sold popcorn and

has worked his way with his great handicap

through school and through college, and

graduated as a doctor, and gone to Europe and

taken another degree; Dr. Sweet, who knew more

than any man in the neighborhood ever would know

or ever want to know. He deserved more for all

he had done. When they heard he was coming, then

it was time to act, and act together, for the

sake of their homes, their families and their

firesides, and so they got together. They didn't

wait. A meeting was called in the neighborhood;

we haven't a record of that, but we have a

record of another one.

And then, what happened after that? Let me read

you, not from the books of any organization; not

from colored people; from what I have learned is

a perfectly respectable paper, so far as papers

go, the Detroit Free Press.

Mr. Toms: Free

Press, the best morning paper.

Mr. Darrow: And

the only real Free Press that I ever heard of.

On July 12th, gentlemen, a month after Dr. Sweet

had bought his home, this appears in the paper,

the headlines: "Stop Rioting." "Smith Pleads

with Citizens. Detroit Faces Shame and Disgrace

as the Result of Fighting, he states." "Negro,

held for shooting youth, vacates residence under

police guard."

Here is the story,

not published in colored papers: "While Detroit

police were anticipating further outbreaks near

the homes occupied by Negroes in white

residential areas and had full complements of

reserves in readiness to deal with any situation

that might arise, Mayor John W. Smith late

yesterday issued a statement asking the public

to see that the riots ‘do not grow into a

condition which will be a lasting stain on the

reputation of Detroit as a law-abiding

community."

"The storm centers

are considered to be American and Tireman

Avenues [in southwestern Detroit] where

Vollington A. Bristol, Negro undertaker ..."

Excuse me. This isn't the only time I ever heard

of that Tireman Avenue.

"The storm centers

are considered to be American and Tireman

Avenues where Vollington A. Bristol, Negro

undertaker still occupies the home he recently

purchased there in the teeth of demonstrations

on three successive nights and a residence on

Prairie Avenue, near Grand River Avenue."

"John W. Fletcher,

9428 Stoepel Avenue, two blocks from Livernois

and Plymouth Avenue, the Negro who is to be

charged with causing grievous bodily harm in

connection with the shooting of a white youth,

Leonard Paul, 15 years old, 9567 Prairie Avenue,

Friday night, relieved the situation in his

district by moving out yesterday after less than

forty-eight hours tenancy. Six patrolmen, under

Lieutenant A. R. Saal of the Petosky Avenue

Station, were at hand as Fletcher moved his

furniture over his brick-strewn lawn from the

house in which not one window remained whole."

Gentlemen, what

kind of feeling does it give a white man? It

makes me ashamed of my race. Now, to go on:

"There was no

trouble. Latest reports from Receiving Hospital

indicates that the youth, Paul, who was twice

shot in the hip by Fletcher, according to the

latter's alleged statement, is still in a

serious condition. Although no demonstrations

were held up to a late hour last night, police

guards will be maintained for an indefinite

period about the three homes, it was announced.

Two of the houses have been purchased and

occupied by Negro families, and negotiations are

under way for the purchase of the third by a

Negro, according to rumors which have reached

the police. The latter is on Prairie Avenue."

"The police

armored car, which was conditioned early last

week and has been held in readiness in case of

trouble, last night was moved near the scene of

the recent disturbances. It will remain for the

present in the vicinity of Tireman and American

Avenues. Every available policeman and

detective, and fifty deputy sheriffs also have

been detailed to the locality."

"A meeting,

attended by more than ten thousand persons, was

held on West Fourth Street, a mile west of

Lincoln Park Village last night. A speaker from

Tennessee advocated laws to compel Negroes to

live only in certain quarters of the city."

I don't know

whether he was one of the policemen who was up

at the Sweet house. This speaker was from

Tennessee.

"The only incident

noted occurred when Bristol left this house. As

he greeted Sergeant Welsh and two officers who

stood on guard, an automobile passed by and

swerved towards the pavement where the Negro

was. The latter jumped back hurriedly, and the

car kept on its way."

Mayor Smith's statement is as follows:

"Recent incidents

of violence and attempted violence in connection

with racial disagreements constitute a warning

to the people of Detroit which they cannot

afford to ignore. They are to be deplored, and

it is a duty which rests as much upon the

citizenry as upon the public officials to see

that they do not grow into a condition which

will be a lasting stain upon the reputation of

Detroit as a law-abiding community."

"The police

department can have but one duty in connection

with all such incidents, that is to use its

utmost endeavors to prevent the destruction of

life and property. In the performance of this

duty, I trust that every police officer will be

unremitting in his efforts. The law recognizes

no distinction in color or race. On all

occasions when the emotions are deeply stirred

by controversy, the persons affected on all

sides of the dispute are likely to feel that the

police or other controlling force are siding

against them. I hope and believe that the police

during the recent attempts to preserve law and

order have done so impartially."

"With the police

department doing its utmost to preserve order,

there is always the possibility that

uncontrolled elements may reach such proportions

that even these efforts will not be completely

effectual. It is that fact that calls for

earnest cooperation by all good citizens at this

time. Curiosity seekers who go to scenes of

threatened disorder add immeasurably to the

problem of preserving order. Thus, the persons

innocent of ill intentions are likely to be

chiefly responsible for inexcusable incidents."

"The condition

which faces Detroit is one which faced

Washington, East St. Louis, Chicago and other

large cities. The result in those cities was one

which Detroit must avoid, if possible. A single

fatal riot would injure this city beyond

remedy."

"The avoidance of

further disorder belongs to the good sense of

the leaders of thought in both white and colored

races. The persons either white or colored who

attempt to urge their fellows on to disorder and

crime are guilty of the most serious offense

upon the statute books. It is clear that a

thoughtless individual of both races constitutes

the nucleus in each disorder, and it is equally

clear that the inspiration for their acts comes

from malign influences which are willing to go

even to the limits of bloodshed to gain their

ends. The police are expected to inquire and

prosecute any persons active in organizing such

disorder or inciting a riot. The rest of the

duty for preserving order lies with the

individual citizens--by refraining from adding

to the crowds in districts where danger exists,

from refraining from discussion which may have a

tendency to incite disorder, and finally to

rebuke at once the individual agitators who are

willing to risk human life, destroy property,

and ruin their city's reputation."

That is the

Mayor's proclamation. The newspaper adds this:

"To maintain the high standard of the

residential district between Jefferson and Mack

Avenues, a meeting has been called by the Water

Works Improvement Association for Thursday night

in the Howe School auditorium. Men and women of

the district, which includes Cadillac, Hurlburt,

Bewick, Garland, St. Clair, and Harding Avenues,

are asked to attend in self-defense."

I shall not talk

to you much longer. I am sorry I have talked so

long. But this case is close to my heart. These

colored people read this story in the paper. Do

I need to go anywhere else to find the feeling

of peril over the question of color? Dr. Sweet

had to face the same proposition. Two nights

after this story was in the paper, at the Howe

School, across the street from Dr. Sweet's

house, seven hundred people of the neighborhood

were present; two detectives, and all the

neighbors, and in their presence, a man from

Tireman Avenue, who they say was radical, and

who, this good gentleman, Mr. Andrews, says,

called a spade a spade. Well, well, what do you

know about that? He called a spade a spade. I

suppose Andrews meant that he called a black man

a "nigger," and "said that where the nigger

showed his head, the white must shoot." He

advocated force and violence. He told what had

happened in his own neighborhood. He told of

driving people out of their homes, and said that

the Tireman Avenue Improvement Association could

be called on to help at Garland and Charlevoix.

Gentlemen, we know

the work of an improvement association. If you

can only get enough improvement associations in

the City of Detroit, Detroit will be improved.

This meeting occurred July the 14th, and Sweet

moved into the house September 8th. The people

knew it. They were confronted with the mob.

Their house was stoned. Their windows were

broken. No more riotous combination ever came

together than the one that was there assembled.

Who are these people who were in this house?

Were they people of character? Were they people

of standing? Were they people of intelligence?

First, there was

Doctor Sweet. Gentlemen, a white man does pretty

well when he does what Doctor Sweet did. A white

boy who can start in with nothing, and put

himself through college, study medicine, taking

post graduate work in Europe, earning every

penny of it as he goes along, shoveling snow and

coal, and working as a bell hop, on boats,

working at every kind of employment that he can

get to make his way, is some fellow.

But, Dr. Sweet has

the handicap of the color of his face. And there

is no handicap more terrible than that.

Supposing you had your choice, right here this

minute, would you rather lose your eyesight or

become colored? Would you rather lose your

hearing or be a Negro? Would you rather go out

there on the street and have your leg cut off by

a street car, or have a black skin?

I don't like to

speak of it; I do not like to speak of it in the

presence of these colored people, whom I have

always urged to be as happy as they can. But, it

is true, Life is a hard game, anyhow. But, when

the cards are stacked against you, it is

terribly hard. And they are stacked against a

race for no reason but that they are black.

Who are these men

who were in this house? There was Doctor Sweet.

There was his brother, who was a dentist. There

was this young boy who worked his way for three

years through college, with a little aid from

his brother, and who was on his way to graduate.

Henry's future is now in your hands. There was

his companion, who was working his way through

college,--all gathered in that house.

Were they

hoodlums? Were they criminals? Were they

anything except men who asked for a chance to

live; who asked for a chance to breathe the free

air and make their own way, earn their own

living, and get their bread by the sweat of

their brow?

I will read to you what the Mayor said. I will

call your attention to one sentence in it again,

and then let us see what the mob did. This was

the Mayor of your City, whose voice should be

heard, who speaks of the danger that is imminent

to this city and to every other city in the

north, a danger that may bear fruit at any time;

and he called the attention of the public of

this city to this great danger, gentlemen. And,

I want to call your attention to it. Here is

what he said:

"The avoidance of

further disorder belongs to the good sense of

the leaders of thought of both white and colored

races. The persons, either white or colored, who

attempt to urge their fellows to disorder and

crime, are guilty of the most serious offences

upon the statute books."

Gentlemen, were

those words of wisdom? Are they true? They were

printed in this newspaper on the 12th day of

July. Two days later, on the schoolhouse

grounds, a crowd of seven or eight hundred

assembled, and listened to a firebrand who arose

in that audience and told the people that his

community had driven men and women from their

homes because they were black; that the Tireman

Avenue people knew how to deal with them, and

advised the mob to violate the law and the

constitution and the rights of the black;

advised them to take the law into their own

hands, and to drive these poor dependent people

from their own homes. And, the crowd cheered;

while the officers of the law were there, all

within two days of the time the Mayor of this

city had called the attention of the public to

the fact that any man was a criminal of the

worst type who would do anything to stir up

sedition or disobedience to the law in relation

to color.

The man is more

than a firebrand who invited and urged crime and

violence in his community. No officer raised his

hand to prosecute, and no citizen raised his

voice, while this man uttered those treasonable

words across the street from where Sweet had

purchased his home, and in the presence of seven

hundred people. Did anybody say a thing? Did

anybody rise up in that audience and say: "We

respect and shall obey the law; we shall not

turn ourselves into a mob to destroy black men

and to batter down their homes, in spite of what

they did on Tireman Avenue."

Gentlemen, these black men shot. Whether any

bullets from their guns hit Breiner, I do not

care. I will not discuss it. It is passing

strange that the bullet that went through him,

went directly through, not as if it was shot

from some higher place. It was not the bullet

that came from Henry Sweet's rifle; that is

plain. It might have come from the house; I do

not know, gentlemen, and I do not care. There

are bigger issues in this case than that. The

right to defend your home, the right to defend

your person, is as sacred a right as any human

being could fight for, and as sacred a cause as

any jury could sustain.

That issue not

only involves the defendants in this case, but

it involves every man who wants to live, every

man who wants freedom to work and to breathe; it

is an issue worth fighting for, and worth dying

for, it is an issue worth the attention of this

jury, who have a chance that is given to few

juries to pass upon a real case that will mean

something in the history of a race.

These men were taken to the police station.

Gentlemen, there was never a time that these

black men's rights were protected in the least;

never once. They had no rights, they are black.

They were to be driven out of their home, under

the law's protection. When they defended their

home, they were arrested and charged with

murder. They were taken to a police station,

manacled. And they asked for a lawyer. And,

every man, if he has any brains at all, asks for

a lawyer when he is in the hands of the police.

If he does not want to have a web woven around

him, to entangle or ensnare him, he will ask for

a lawyer. And, the lawyer's first aid to the

injured always is, "Keep your mouth shut." It is

not a case of whether you are guilty or not

guilty. That makes no difference. "Keep your

mouth shut." The police grabbed them, as is

their habit. They got the County Attorney to ask

questions.

What did they do? They did what everybody does,

helpless, alone, and unadvised. They did not

know, even, that anybody was killed. At least

there is no evidence that they knew. But, they

knew that they had been arrested for defending

their own rights to live; and they were there in

the hands of their enemies; and they told the

best story they could think of at the

time,--just as ninety-nine men out of a hundred

always do. Whether they are guilty or not guilty

makes no difference. But lawyers, and even

policemen, should have protected their rights.

Some things that

these defendants said were not true, as is

always the case. The prosecutor read a statement

from this boy, which is conflicting. In two

places he says that he shot "over them." In

another he said that he shot "at them." He

probably said it in each place but the reporter

probably got one of them wrong. But Henry makes

it perfectly explicit, and when you go to your

jury room and read it all, you will find that he

does. In another place he said he shot to defend

his brother's home and family. He says that in

two or three places. You can also find he said

that he shot so that they would run away, and

leave them to eat their dinner. They are both

there. These conflicting statements you will

find in all cases of this sort. You always find

them, where men have been sweated, without help,

without a lawyer, groping around blindly, in the

hands of the enemy, without the aid of anybody

to protect their rights. Gentlemen, from the

first to the last, there has not been a

substantial right of these defendants that was

not violated.

We come now and lay this man's case in the hands

of a jury of our peers,--the first defense and

the last defense is the protection of home and

life as provided by our law. We are willing to

leave it here. I feel, as I look at you, that we

will be treated fairly and decently, even

understandingly and kindly. You know what this

case is. You know why it is. You know that if

white men had been fighting their way against

colored men, nobody would ever have dreamed of a

prosecution. And you know that, from the

beginning of this case to the end, up to the

time you write your verdict, the prosecution is

based on race prejudice and nothing else.

Gentlemen, I feel deeply on this subject; I

cannot help it. Let us take a little glance at

the history of the Negro race. It only needs a

minute. It seems to me that the story would melt

hearts of stone. I was born in America. I could

have left it if I had wanted to go away.

Some other men,

reading about this land of freedom that we brag

about on the 4th of July, came voluntarily to

America. These men, the defendants, are here

because they could not help it. Their ancestors

were captured in the jungles and on the plains

of Africa, captured as you capture wild beasts,

torn from their homes and their kindred; loaded

into slave ships, packed like sardines in a box,

half of them dying on the ocean passage; some

jumping into the sea in their frenzy, when they

had a chance to choose death in place of

slavery. They were captured and brought here.

They could not help it. They were bought and

sold as slaves, to work without pay, because

they were black.

They were

subjected to all of this for generations, until

finally they were given their liberty, so far as

the law goes,--and that is only a little way,

because, after all, every human being's life in

this world is inevitably mixed with every other

life and, no matter what laws we pass, no matter

what precautions we take, unless the people we

meet are kindly and decent and human and

liberty-loving, then there is no liberty.

Freedom comes from human beings, rather than

from laws and institutions.

Now, that is their

history. These people are the children of

slavery. If the race that we belong to owes

anything to any human being, or to any power in

this Universe, they owe it to these black men.

Above all other men, they owe an obligation and

a duty to these black men which can never be

repaid. I never see one of them, that I do not

feel I ought to pay part of the debt of my race,

and if you gentlemen feel as you should feel in

this case, your emotions will be like mine.

Gentlemen, you

were called into this case by chance. It took us

a week to find you, a week of culling out

prejudice and hatred. Probably we did not cull

it all out at that; but we took the best and the

fairest that we could find. It is up to you.

Your verdict means something in this case: It

means something, more than the fate of this boy.

It is not often that a case is submitted to

twelve men where the decision may mean a

milestone in the progress of the human race. But

this case does. And, I hope and I trust that you

have a feeling of responsibility that will make

you take it and do your duty as citizens of a

great nation, and, as members of the human

family, which is better still.

Let me say just a

parting word for Henry Sweet, who has well nigh

been forgotten. I am serious, but it seems

almost like a reflection upon this jury to talk

as if I doubted your verdict. What has this boy

done? This one boy now that I am culling out

from all of the rest, and whose fate is in your

hands,--can you tell me what he has done? Can I

believe myself? Am I standing in a Court of

Justice, where twelve men on their oaths are

asked to take away the liberty of a boy

twenty-one years of age, who has done nothing

more than what Henry Sweet has done?

Gentlemen, you may

think he shot too quick; you may think he erred

in judgment; you may think that Doctor Sweet

should not have gone there, prepared to defend

his home. But, what of this case of Henry Sweet?

What has he done? I want to put it up to you,

each one of you, individually. Doctor Sweet was

his elder brother. He had helped Henry through

school. He loved him. He had taken him into his

home. Henry had lived with him and his wife; he

had fondled his baby. The doctor had promised

Henry money to go through school. Henry was

getting his education, to take his place in the

world, gentlemen--and this is a hard job. With

his brother's help, he had worked himself

through college up to the last year. The doctor

had bought a home. He feared danger. He moved in

with his wife and he asked this boy to go with

him. And this boy went to help defend his

brother, and his brother's wife and his child

and his home.

Do you think more

of him or less of him for that? I never saw

twelve men in my life--and I have looked at a

good many faces of a good many juries,--I never

saw twelve men in my life, that, if you could

get them to understand a human case, were not

true and right.

Should this boy

have gone along and helped his brother? Or,

should he have stayed away? What would you have

done? And yet, gentlemen, here is a boy, and the

President of his College came all the way here

from Ohio to tell you what thinks of him. His

teachers have come here, from Ohio, to tell you

what they think of him. The Methodist Bishop has

come here to tell you what he thinks of him.

So, gentlemen, I

am justified in saying that this boy is as

kindly, as well disposed, as decent a man as any

one of you twelve. Do you think he ought to be

taken out of his school and sent to the

penitentiary? All right, gentlemen, if you think

so, do it. It is your job, not mine. If you

think so, do it. But if you do, gentlemen, if

you should ever look into the face of your own

boy, or your own brother, or look into your own

heart, you will regret it in sack cloth and

ashes. You know, if he committed any offense, it

was being loyal and true to his brother whom he

loved. I know where you will send him, and it

will not be to the penitentiary.

Now, gentlemen, just one more word, and I am

through with this case. I do not live in

Detroit. But I have no feeling against this

city. In fact, I shall always have the kindest

remembrance of it, especially if this case

results as I think and feel that it will. I am

the last one to come here to stir up race

hatred, or any other hatred. I do not believe in

the law of hate. I may not be true to my ideals

always, but I believe in the law of love, and I

believe you can do nothing with hatred. I would

like to see a time when man loves his fellow

man, and forgets his color or his creed. We will

never be civilized until that time comes.

I know the Negro

race has a long road to go. I believe the life

of the Negro race has been a life of tragedy, of

injustice, of oppression. The law has made him

equal, but man has not. And, after all, the last

analysis is, what has man done?--and not what

has the law done? I know there is a long road

ahead of him, before he can take the place which

I believe he should take. I know that before him

there is suffering, sorrow, tribulation and

death among the blacks, and perhaps the whites.

I am sorry. I would do what I could to avert it.

I would advise patience; I would advise

toleration; I would advise understanding; I

would advise all of those things which are

necessary for men who live together.

Gentlemen, what do

you think is your duty in this case? I have

watched, day after day, these black, tense faces

that have crowded this court. These black faces

that now are looking to you twelve whites,

feeling that the hopes and fears of a race are

in your keeping.

This case is about

to end, gentlemen. To them, it is life. Not one

of their color sits on this jury. Their fate is

in the hands of twelve whites. Their eyes are

fixed on you, their hearts go out to you, and

their hopes hang on your verdict.

This is all. I ask

you, on behalf of this defendant, on behalf of

these helpless ones who turn to you, and more

than that, on behalf of this great state, and

this great city which must face this problem,

and face it fairly, I ask you, in the name of

progress and of the human race, to return a

verdict of not guilty in this case!

This is page 1 of

2. Go to

page 1.

page 1.

More History

|

|