|

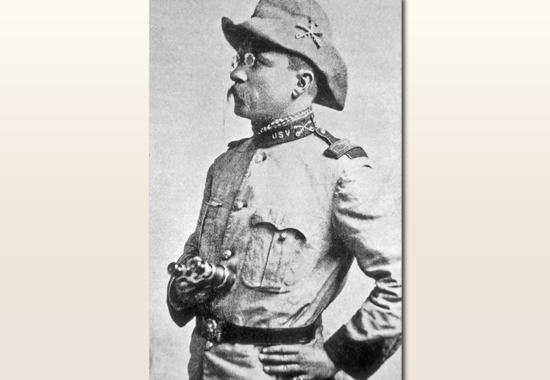

THE MAN WHO DOES NOT SHRINK FROM HARDSHIP - ROOSEVELT 1899

The Strenuous Life

It follows the full text transcript of

Theodore Roosevelt's The Strenuous Life speech, delivered at

Chicago, Illinois - April 10, 1899.

|

In speaking to

you, men of the greatest city of the West, |

men of the State

which gave to the country Lincoln and Grant, men

who preeminently and distinctly embody all that

is most American in the American character, I

wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble

ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life,

the life of toil and effort, of labor and

strife; to preach that highest form of success

which comes, not to the man who desires mere

easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink

from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil,

and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate

triumph.

A life of slothful ease, a life of that peace

which springs merely from lack either of desire

or of power to strive after great things, is as

little worthy of a nation as of an individual. I

ask only that what every self-respecting

American demands from himself and from his sons

shall be demanded of the American nation as a

whole. Who among you would teach your boys that

ease, that peace, is to be the first

consideration in their eyes-to be the ultimate

goal after which they strive? You men of Chicago

have made this city great, you men of Illinois

have done your share, and more than your share,

in making America great, because you neither

preach nor practice such a doctrine.

You work

yourselves, and you bring up your sons to work.

If you are rich and worth your salt, you will

teach your sons that though they may have

leisure, it is not to be spent in idleness; for

wisely used leisure merely means that those who

possess it, being free from the necessity of

working for their livelihood, are all bound to

carry on some kind of non-remunerative work in

science, in letters, in art, in exploration, in

historical research-work of this type we most

need in this country, the successful carrying

out of which reflects most honor upon the

nation. We do not admire the man of timid peace.

We admire the man who embodies victorious

effort; the man who never wrongs his neighbor,

who is prompt to help a friend, but who has

those virile qualities necessary to win in the

stern strife of actual life. It is hard to fail,

but it is worse to never have tried to succeed.

In this life we get nothing save by effort.

Freedom from

effort in the present merely means that there

has been some stored up effort in the past. A

man can be freed from the necessity of work only

by the fact that he or his fathers before him

have worked to good purpose. If the freedom thus

purchased is used aright, and the man still does

actual work, though of a different kind, whether

as a writer or as a general, whether in the

field of politics or in the field of exploration

and adventure, he shows he deserves his good

fortune. But if he treats this period of freedom

from the need of actual labor as a period , not

of preparation, but of mere enjoyment, even

though perhaps not of the vicious enjoyment, he

shows that he is simply a cumberer of the

earth's surface, and he surely unfits himself to

hold his own with his fellows if the need to do

so should again arise. A mere life of ease is

not in the end a very satisfactory life, and,

above all, it is a life which ultimately unfits

those who follow it for serious work in the

world.

In the last analysis a healthy state can exist

only when the men and women who make it up can

lead clean, vigorous, healthy lives; when the

children are so trained that they shall

endeavor, not to shirk difficulties, but to

overcome them; not to seek ease, but to know how

to rest triumph from toil and risk. The man must

be glad to do a man's work, to dare and endure

and to labor; to keep himself, and those

dependent on him. The woman must be the

housewife, the helpmeet of the homemaker, the

wise and fearless mother of many healthy

children. In one of Daudet's powerful and

melancholy books he speaks of "the fear of

maternity, the haunting terror of the young wife

of the present day." When such words can be

truthfully written of a nation, that nation is

rotten to the heart's core. When men fear work

or fear of righteous war, when women fear

motherhood, they tremble on the brink of doom;

and well it is they should vanish from the

earth, where they are fit subjects for the scorn

of all men and women who are themselves strong

and brave and high-minded.

As it is with the individual, so it is with the

nation. It is a base untruth to say that happy

is the nation that has no history. Thrice happy

is the nation that has a glorious history. Far

better it is to dare mighty things, to win

glorious triumphs, even though checkered by

failure, than to take rank with those poor

spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much,

because they live in the gray twilight that

knows not victory nor defeat. If in 1861 the men

who loved the Union had believed that peace was

the end of all things, and war and strife the

worst of all things, and had acted upon their

belief, we would have saved hundreds of

thousands of lives, we would have saved hundreds

of millions of dollars. Moreover, besides saving

all the blood and treasure we then lavished, we

would have prevented the heartbreak of many

women, the dissolution of many homes, and we

would have spared the country those months of

doom and shame when it seemed as if our armies

marched only to defeat.

We could have

avoided all this suffering simply by shrinking

from strife. And if we had thus avoided it, we

would have shown that we were weaklings, and

that we were unfit to stand among the great

nations of the earth. Thank God for the iron in

the blood of our fathers, the men who upheld the

wisdom of Lincoln, and bore the sword or rifle

in the armies of Grant! Let us, the children of

the men who proved themselves equal to the

mighty days, let us, the children of the men who

carried the great Civil War to a triumphant

conclusion, praise the God of our fathers that

the ignoble counsels of peace were rejected;

that the suffering and loss, the blackness of

sorrow and despair, were unflinchingly faced,

and the years of strife endured; for in the end

the slave was freed, the Union restored, and the

mighty American republic placed once more as a

helmeted queen among nations.

We of this generation do not have to face a task

such as that our fathers faced, but we have our

tasks, and woe to us if we fail to perform them!

We cannot, if we would, play the part of China,

and be content to rot by inches in ignoble ease

within our borders, taking no interest in what

goes on beyond them, sunk in scrambling

commercialism; heedless of higher life, the life

of aspiration, of toil and risk, busying

ourselves only with the wants of our bodies for

the day, until suddenly we should find, beyond a

shadow of question, what China has already

found, that in this world the nation that has

trained itself into a career of unwarlike and

isolated ease is bound, in the end, to go down

before other nations which have not lost the

manly and adventurous qualities. If we are to be

a really great people, we must strive in good

faith to play a great part in the world. We

cannot avoid meeting great issues. All that we

can determine for ourselves is whether we shall

meet them well or ill.

In 1898 we could

not help being brought face to face with the

problem of war with Spain. All we could decide

was whether we should shrink like cowards from

the contest, or enter into it as beseemed a

brave and high-spirited people; and, once in,

whether failure or success shall crown our

banners. So it is now. We cannot avoid the

responsibilities that confront us in Hawaii,

Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Phillippines. All we

can decide is whether we shall meet them in a

way that will redound to the national credit, of

whether we shall make of our dealings with these

new problems a dark and shameful page in our

history. To refuse to deal with them at all

merely amounts to dealing with them badly. We

have a given problem to solve. If we undertake

the solution, there is, of course, always danger

that we may not solve it aright; but to refuse

to undertake the solution simply renders it

certain that we cannot possibly solve it aright.

The timid man, the lazy man, the man who

distrusts his country, the over-civilized man,

who has lost the great fighting, the masterful

values, the ignorant man, and the man of dull

mind, whose soul is incapable of feeling the

mighty lift that thrills "stern men with empires

in their brains"-all these, of course, shrink

from seeing the nation undertake its new duties;

shrink from seeing us build a navy and an army

adequate to our needs; shrink from seeing us do

our share of the world's work, by bringing order

out of the chaos in the great, fair tropic

islands from which the valor of our soldiers and

sailors has driven the Spanish flag.

These are the men

who fear the strenuous life, who fear the only

national life which is really worth leading.

They believe in that cloistered life which saps

the hearty virtues in a nation, as it saps them

in the individual; or else they are wedded to

that base spirit of grain and greed which

recognizes commercialism the be-all and end-all

of national life, instead of realizing that,

though an indispensable element, it is, after

all, but one of the many elements that go to

make up true national greatness. No country can

long endure if its foundations are not laid deep

in the material prosperity which comes from

thrift, from business energy and enterprise,

from hard, unsparing efforts in the fields of

industrial activity; but neither was any nation

ever yet truly great if it relied upon material

prosperity alone. All honor must be paid to the

architects of our material prosperity, to the

great captains of industry who have built our

factories and our railroads, to the strong men

who toil for wealth with brain or hand; for

great is the debt of the nation to these and

their kind. But our debt is yet greater to the

men whose highest type is to be found in a

statesman like Lincoln, a soldier like Grant.

They showed by their lives that they recognized

the law of work, the law of strife; they toiled

to win a competence for themselves and those

dependent upon them; but they recognized that

there were yet other and even loftier duties -

duties to the nation and duties to the race.

We cannot sit huddled within our own borders and

avow ourselves merely an assemblage of

well-to-do hucksters who care nothing for what

happens beyond. Such a policy would defeat even

its own end; for as the nations grow to have

ever wider and wider interests, and are brought

into closer and closer contact, if we are to

hold our own in the struggle for naval and

commercial supremacy, we must build up our power

without our own borders. We must build the

isthmian canal, and we must grasp the points of

vantage which will enable us to have our say in

deciding the destiny of the oceans of the East

and the West.

So much for the commercial side. From the

standpoint of international honor the argument

is even stronger. The guns that thundered off

Manila and Santiago left us echoes of glory, but

they also left us a legacy of duty. If we drove

out a mediaeval tyranny only to make room for

savage anarchy, we had better not begun the task

at all. It is worse than idle to say that we

have no duty to perform, and can leave to their

fates the islands we have conquered. Such a

course would be a course of infamy. It would be

followed at once by utter chaos in the wretched

islands themselves. Some stronger, manlier power

would have to step in and do the work, and we

would have shown ourselves weaklings, unable to

carry to successful completion the labors that

great and high-spirited nations are eager to

undertake.

The work must be done; we cannot escape our

responsibility; and if we are worth our salt, we

shall be glad of the chance to do the work -

glad of the chance to show ourselves equal to

one of the great tasks set modern civilization.

But let us not deceive ourselves as to the

importance of the task. Let us not be mislead by

the vainglory into underestimating the strain it

will put on our powers. Above all, let us, as we

value our own self-respect, face the

responsibilities with proper seriousness,

courage and high resolve. We must demand the

highest order of integrity and ability in our

public men who are to grapple with these new

problems. We must hold to a rigid accountability

those public servants who show unfaithfulness to

the interests of the nation or the inability to

rise to the high level of the new demands upon

our strength and our resources.

Of course we must remember not to judge any

public servant by any one act, and especially

should we beware of attacking the men who are

merely the occasions and not the causes of

disaster. Let me illustrate what I mean by the

army and the navy. If twenty years ago we had

gone to war, we should have the navy as

absolutely unprepared as the army. At that time

our ships could not have encountered with

success the fleets of Spain any more than

nowadays we can put untrained soldiers, no

matter how brave, who are armed with archaic

black-powder weapons, against well-drilled

regulars armed with the highest type of modern

repeating rifle. But in the early eighties the

attention of the nation became directed to our

naval deeds.

Congress most

wisely made a series of appropriations to build

up a new navy, and under a succession of able

and patriotic secretaries, of both political

parties, the navy was gradually built up, until

its material became equal to its splendid

personnel, with the result that in the summer of

1898 it leaped to its proper place as one of the

most brilliant and formidable fighting navies in

the entire world. We rightly pay all honor to

the men controlling the navy at the time it won

these great deeds, honor to Secretary Long and

Admiral Dewey, to the captains who handled the

ships in action, to the daring lieutenants who

braved death in the smaller craft, and to the

heads of the bureaus at Washington who saw that

the ships were so commanded, so armed, so

equipped, so well engined, as to insure the best

results. But let us also keep ever in mind that

all of this would not have availed if it had not

been for the wisdom of the men who during the

preceding fifteen years had built up the navy.

Keep in mind the

secretaries of the navy during those years; keep

in mind the senators and congressmen who by

their votes gave the money necessary to build

and to armor the ships, to construct the great

guns, and to train the crews; remember also

those who actually did build the ships, the

armor, and the guns; and remember the admirals

and captains who handled battle-ship, cruiser,

and torpedo-boat on the high seas, alone and in

squadrons, developing the seamanship, the

gunnery, and the power of acting together, which

their successors utilized so gloriously at

Manila and off Santiago. And, gentleman,

remember the converse, too. Remember that

justice has two sides. Be just to those who

built up the navy, and, for the sake of the

future of the country, keep in mind those who

opposed its building up. Read the "Congressional

Record." Find out the senators and congressmen

who opposed the grants for building the new

ships; who opposed the purchase of armor,

without which the ships were worthless; who

opposed any adequate maintenance for the Navy

Department, and strove to cut down the number of

men necessary to man our fleets. The men who did

these things were one and all working to bring

disaster on the country. They have no share in

the glory of Manila, in the honor of Santiago.

They have no cause to feel proud of the valor of

our sea-captains, of the renown of our flag.

Their motives may or may not have been good, but

their acts were heavily fraught with evil. They

did ill for the national honor, and we won in

spite of their sinister opposition.

Now, apply all this to our public men of to-day.

Our army never has been built up as it should be

built up. I shall not discuss with an audience

this puerile suggestion that a nation of seventy

millions of freemen is in danger of losing its

liberties from the existence of an army of one

hundred thousand men, three fourths of whom will

be employed in foreign islands, in certain coast

fortresses, and on Indian reservations. No man

of good sense and stout heart can such a

proposition seriously. If we are such weaklings

as the proposition implies, then we are unworthy

of freedom in any event. To no body of men in

the United States is the country so much

indebted as to the splendid officers and

enlisted men of the regular army and navy. There

is no body from which the country has less to

fear, and none of which it should be prouder,

none which it should be more anxious to upbuild.

Our army needs complete reorganization, not

merely enlarging, and the reorganization can

only come as a result of legislation. A proper

general staff should be established, and the

positions of ordnance, commissary, and

quartermaster officers should be filled by

detail from the line. Above all, the army must

be given the chance to exercise in large bodies.

Never again should we see, as we saw in the

Spanish war, major-generals in command of

divisions who had never before commanded three

companies together in the field. Yet, incredible

to relate, Congress has shown a queer inability

to learn some of the lessons of war. There were

large bodies of men in both branches who opposed

the declaration of war, who opposed the

ratification of peace, who opposed the

upbuilding of the army, and who even opposed the

purchase of the armor at a reasonable price for

the battle-ships and cruisers, thereby putting

an absolute stop to the building of any new

fighting ships for the navy.

If, during the

years to come, any disaster should befall our

arms, afloat or ashore, and thereby should shame

the United States, remember the blame will lie

upon the men whose names appear on the

roll-calls of Congress on the wrong side of

these great questions. On them will lie the

burden of the loss of our soldiers and sailors,

of any dishonor to the flag; and upon you and

the people of this country will lie the blame if

you do not repudiate, in no unmistakable way,

what these men have done. The blame will not

rest upon the untrained commander of the untried

troops, upon the civil officers of a department

the organization of which has been left utterly

inadequate, or upon the admiral with an

insufficient number of ships; but upon the

public men who have so lamentably failed in

forethought as to refuse to remedy these evils

long in advance, and upon the nation that stands

behind those public men.

So, at the present hour, no small share of the

responsibility for the blood shed in the

Philippines, the blood of our brothers, and the

blood of their wild and ignorant foes, lies at

the thresholds of those who so long delayed the

adoption of the treaty of peace, and of those

who by their worse than foolish words

deliberately invited a savage people to plunge

into a war fraught with sure disaster for them-a

war, too, in which our own brave men who follow

the flag must pay with their blood for the

silly, mock humanitarianism of the prattlers who

sit at home in peace.

The army and the navy are the sword and the

shield which this nation must carry if she is to

do her duty among the nations of the earth-if

she is not to stand merely as the China of the

western hemisphere. Our proper conduct towards

the tropic islands we have wrested from Spain is

merely the form of which our duty has taken at

the moment. Of course we are bound to handle the

affairs of our own household well. We must see

that there is civic honesty, civic cleanliness,

civic good sense in our home administration of

the city, State, and nation. We must strive for

honesty in office, for honesty towards the

creditors of the nation and of the individual;

for the widest freedom of the individual

initiative where possible, and for the wisest

control of individual initiative where it is

hostile to the welfare of the many. But because

we set our own household in order we are not

thereby excused from playing our part in the

great affairs of the world. A man's first duty

is to his own home, but he is not thereby

excused from doing his duty to the State; for if

he fails in this second duty it is under the

penalty of ceasing to be a free-man. In the same

way, while a nations first duty in within its

own borders, it is not thereby absolved from

facing its duties in the world as a whole; and

if it refuses to do so, it merely forfeits its

right to struggle for a place among the peoples

that shape the destiny of mankind.

In the West Indies and the Philippines alike was

are confronted by most difficult problems. It is

cowardly to shrink from solving them in the

proper way; for solved they must be, if not by

us, then by some stronger and more manful race.

If we are too weak, too selfish, or too foolish

to solve them, some bolder and abler people must

undertake the solution. Personally, I am far too

firm a believer in the greatness of my country

and the power of my countrymen to admit for one

moment that we shall ever be driven to the

ignoble alternative.

The problems are different for the different

islands. Porto Rico is not large enough to stand

alone. We must govern it wisely and well,

primarily in the interest of its own people.

Cuba is, in my judgment, entitled ultimately to

settle for itself whether it shall be an

independent state or an integral portion of the

mightiest of republics. But until order and

stable liberty are secured, we must remain in

the island to insure them, and infinite tact,

judgment, moderation, and courage must be shown

by our military and civil representatives in

keeping the island pacified, in relentlessly

stamping out brigandage, in protecting all

alike, and yet in showing proper recognition to

the men who have fought for Cuban liberty. The

Philippines offer a yet graver problem. Their

population includes half-caste and native

Christians, warlike Moslems, and wild pagans.

Many of their people are utterly unfit for

self-government and show no signs of becoming

fit. Others may in time become fit but at the

present can only take part in self-government

under a wise supervision, at once firm and

beneficent.

We have driven

Spanish tyranny from the islands. If we now let

it be replaced by savage anarchy, our work has

been for harm and not for good. I have scant

patience with those who fear to undertake the

task of governing the Philippines, and who

openly avow that they do fear to undertake it,

or that they shrink from it because of the

expense and trouble; but I have even scanter

patience with those who make a pretense of

humanitarianism to hide and cover their

timidity, and who cant about "liberty" and the

"consent of the governed," in order to excuse

themselves for their unwillingness to play the

part of men. Their doctrines, if carried out,

would make it incumbent upon us to leave the

Apaches of Arizona to work out their own

salvation, and to decline to interfere in a

single Indian reservation. Their doctrines

condemn your forefathers and mine for ever

having settled in these United States.

England's rule in India and Egypt has been of

great benefit to England, for it has trained up

generations of men accustomed to look at the

larger and loftier side of public life. It has

been of even greater benefit to India and Egypt.

And finally, and most of all, it has advanced

the cause of civilization. So, if we do our duty

aright in the Philippines, we will add to that

national renown which is the highest and finest

part of national life, will greatly benefit the

people of the Philippine Islands, and, above

all, we will play our part well in the great

work of uplifting mankind. But to do this work,

keep ever in mind that we must show in a very

high degree the qualities of courage, of

honesty, and of good judgment. Resistance must

be stamped out. The first and all-important work

to be done is to establish the supremacy of our

flag. We must put down armed resistance before

we can accomplish anything else, and there

should be no parleying, no faltering, in dealing

with our foe. As for those in our own country

who encourage the foe, we can afford

contemptuously to disregard them; but it must be

remembered that their utterances are not saved

from being treasonable merely by the fact that

they are despicable.

When once we have put down armed resistance,

when once our rule is acknowledged, than an even

more difficult task will begin, for then we must

see to it that the islands are administered with

absolute honesty and with good judgment. If we

let the public service of the islands be turned

into prey of the spoils of politician, we shall

have begun to tread the path which Spain trod to

her own destruction. We must send out there only

good and able men, chosen for their fitness, and

not because of their partisan service, and these

men must not only administer impartial justice

to the natives and serve their own government

with honesty and fidelity, but show the utmost

tact and firmness, remembering that, with such

people as those with whom we are to deal,

weakness is the greatest of crimes, and next to

weakness comes lack of consideration for their

principles and prejudices.

I preach to you, then, my countrymen, that our

country calls not for the life of ease but for

the life of strenuous endeavor. The twentieth

century looms before us big with the fate of

many nations. If we stand idly by, if we seek

merely swollen, slothful ease and ignoble peace,

if we shrink from the hard contests where men

must win at the hazard of their lives and at the

risk of all they hold dear, then the bolder and

stronger peoples will pass us by, and will win

for themselves the domination of the world. Let

us therefore boldly face the life of strife,

resolute to do our duty well and manfully;

resolute to be both honest and brave, to serve

high ideals, yet to use practical methods. Above

all, let us shrink from no strife, through hard

and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately

win the goal of true national greatness.

More History

|

|