|

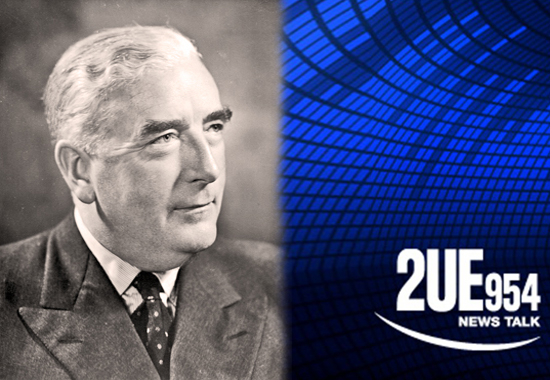

ROBERT MENZIES BROADCASTS ON STATION

2UE, SYDNEY - 1942

Women in War

It follows the full text transcript of

Robert Menzies' Women in War

speech, broadcast from Sydney, Australia — February

20, 1942.

|

There is no more

popular fashion than that of calling ourselves |

realists. But what

is "realism"?

Surely it is a

state of mind in which the thinker has put on

one side all sentiment or prejudice or

self-delusion. In other words, realism involves

facing the facts, whatever they may be, and

acting in accordance with them.

On no question is a realistic approach so

necessary but so rare as it is on the question

of war employment of women. Tonight I want to

take a few moments of your time in clearing up,

if I can, your minds and my own on a problem

which is of increasing importance and urgency.

We have grown up with what might be called all

sorts of taboos and superstitions and

conventions on this matter. We say, perhaps a

little artificially, that women should not do

this or that kind of work, and that if

circumstances do require that they should work,

the task should have a quality of gentility.

Now, what is the truth about the kind of work

that women can do - and particularly about the

kind of work that women can do in the war? I

should like to answer that question by reference

to my own experience of observing war work in

Great Britain last year.

Many hundreds of thousands of women were

actively engaged in the war effort - not only in

nursing and hospital services, but in scores of

other ways. The Auxiliary Territorials were

doing clerical work, were driving cars, were

carrying on administrative activities.

At operational

headquarters of branches of the air force I saw

hundreds of young women in uniform doing, with

speed and accuracy, work of the greatest

importance. At the fire stations of London,

scattered right through the blitz area, there

were hundreds of women - young and not so young

- dressed in the blue overalls of the auxiliary

fire service; not merely standing around and

looking picturesque, but working hard and fast,

reporting fires, telephoning, doing a mass of

clerical work which before the war was done by

men.

And it did not end there. When the bombs came

down and the fires started there were young

women of the auxiliary fire service driving

cars, driving other vehicles, operation

courageously in the fire-lit target areas,

coping with incendiary bombs, sweating and

grimy, but playing a part worthy of any brave

man.

Just before I left England, selected women were

being introduced into active army operations,

doing particularly some of the precision work

involved in the anti-aircraft defenses.

In every munitions and aircraft factory that I

saw, there were hundreds and sometimes thousands

of women employed. Some of them of course were

doing fine inspection work where lightness of

touch and accuracy of eye produce speed and

output. But these were a relatively small

proportion . Most of the women at work were

dressed in overalls like men, attending to

lathes and presses, using riveting machines,

wielding hammers, doing in many instances

downright hard manual labor.

As I saw them they were cheerful, with good

nerves, with the right enthusiastic spirit.

I was told more than once that on a morning

after a blitz in some industrial area you could

almost bank on one hundred per cent of the women

employees being on time for work.

In the country districts the increased

production which is being wrung from the soil of

Great Britain is in many instances being wrung

from it by the hard physical toil of women of

the land army.

On every street the woman bus-conductor is a

familiar sight.

So there are hundreds of thousands of women in

uniform, in overalls; but there are millions of

women who, while they form part of no army and

work in no factory, are doing a superb job in an

entirely unadvertised and often unnoticed way.

Today's housewife

in Great Britain has had the whole order of her

life disturbed. She has become a great

improviser, a person of almost infinite

resourcefulness. If the bombs fall and the

electric light system is interrupted or the gas

mains are set on fire or the water pipes burst,

she must be able at almost a moment's notice to

turn her hand to getting, by what means a man

can never understand, a hot meal for her family,

because the day's work must go on and the day's

workers must be fed. After dinner at night,

sitting with her family in her suburban street,

she may find herself called upon to go out with

sand bag and stirrup pump to help to extinguish

incendiary bombs in her area.

What a life! And what amazing courage this is

that can take daily danger almost as a

commonplace!

And, apart altogether from bombs and

destruction, this same housewife is the one who

has had to adjust the routine of household

management to rationing - the rationing of food,

the rationing of clothing, the rationing of

almost everything that people buy.

One could go on for a long time with a catalogue

of this kind of thing. But, in brief, it all

represents a formidable breaking down of old

barriers and old ideas.

No doubt this great movement of women into the

defense of the realm is destroying or impairing

some elements of life which we might have liked

to keep. But we shall be completely unrealistic

if we do not realize that when this war is over

there will no more be a return to the status quo

for women than there will be such a return to

many of our older notions of life.

Now, what are the paramount questions that we in

Australia must answer in relation to this

problem if we are to face frankly our dangers,

and therefore our needs?

The dominant one must be this: Have we ample man

power for all the tasks of this war - including

not only the fighting services, but munitions

production, essential civil production both

primary and secondary, and essential civil

services? (When I use the expression "man

power", I mean man power and not woman power.)

Plainly, we have not ample man power for these

needs in the light of the new and extending and

pressing demands of this war.

Well, then, can we achieve our end by drawing

upon woman power? Plainly, we can to a very

great extent. There should be no prejudice on

this matter. There must be no prejudice on this

matter.

Wherever a woman is willing and able to do some

job, however "unwomanly" that job might have

seemed to the eye of convention or of custom a

few years ago, and her employment in it will

either give us something we lack today or

release a man for a job, fighting or otherwise,

which only a man can do, then there should be no

barrier against the woman doing it. On the

contrary, there should be active encouragement

and direction. That seems to me to be the

essential principle of this matter.

Somebody may say to me that this lifting of many

women out of ordinary domestic affairs, this

taking down of woman from her "pedestal" is

fraught with grave dangers for the future of the

race.

Perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn't. But the

gravest danger to the future of our race is that

we shall be defeated in this war, and we must be

prepared to take much greater risks than the one

to which reference has just been made if victory

is to be ours.

Really, I do not think we need fear the future

on this matter unduly. There is - and every year

I live, every new experience I have convinces me

of it more and more - there is courage, energy,

skill and resource about women which can serve

this land mightily.

And if that is true, will the country not be all

the richer because those qualities have been put

to the highest patriotic use? In the long run,

will our community not be a stronger, better

balanced and more intelligent community when the

last artificial disabilities imposed upon women

by centuries of custom have been removed?

There is no equality so ennobling as an equality

in service. There is perhaps nothing we need

more as a corrective to the patent ills of

democracy than a full brotherhood and sisterhood

in action and sacrifice.

When peace comes and we try to resume our normal

lives we will, I believe, learn one thing among

others as a result of our experiences in this

war. And that thing will be that those thousands

of women who will, before this trial ends, serve

Australia with all the strength of their minds

and hearts and hands, will be the better mothers

of the new generation because in this one they

have been the fighting daughters of their

country.

More History

|

|