|

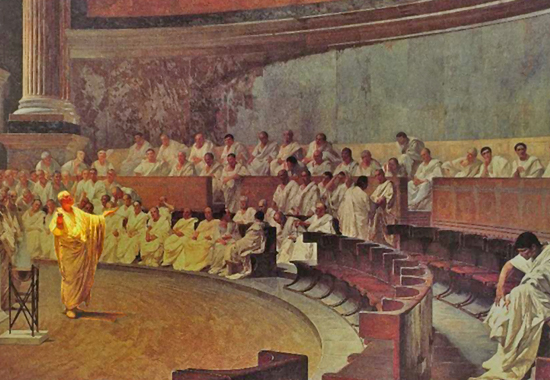

CICERO BREAKS IT DOWN TO THE SENATE

IN ROME

Against Catiline

Go here for more about

Cicero.

Cicero.

Go here for more about

Cicero's Speeches against Catiline.

Cicero's Speeches against Catiline.

It follows the English translation

from

the full text Latin transcript of

Cicero's first speech against Catiline, delivered

in the Temple of Jupiter Stator at Rome - November 8, 63 BC.

|

[1] When, O

Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our

patience? How long is that madness of yours

still to mock us? |

When is there to

be an end of that unbridled audacity of yours,

swaggering about as it does now? Do not the

nightly guards placed on the Palatine Hill—do

not the watches posted throughout the city—does

not the alarm of the people, and the union of

all good men—does not the precaution taken of

assembling the senate in this most defensible

place—do not the looks and countenances of this

venerable body here present, have any effect

upon you? Do you not feel that your plans are

detected? Do you not see that your conspiracy is

already arrested and rendered powerless by the

knowledge which every one here possesses of it?

What is there that you did last night, what the

night before— where is it that you were—who was

there that you summoned to meet you—what design

was there which was adopted by you, with which

you think that any one of us is unacquainted?

[2] Shame on the

age and on its principles! The senate is aware

of these things; the consul sees them; and yet

this man lives. Lives! aye, he comes even into

the senate. He takes a part in the public

deliberations; he is watching and marking down

and checking off for slaughter every individual

among us. And we, gallant men that we are, think

that we are doing our duty to the republic if we

keep out of the way of his frenzied attacks.

You ought, O Catiline, long ago to have been led

to execution by command of the consul. That

destruction which you have been long plotting

against us ought to have already fallen on your

own head.

[3] What? Did not that most illustrious man,

Publius Scipio, (*) the Pontifex Maximus, in his

capacity of a private citizen, put to death

Tiberius Gracchus, though but slightly

undermining the constitution? And shall we, who

are the consuls, tolerate Catiline, openly

desirous to destroy the whole world with fire

and slaughter? For I pass over older instances,

such as how Caius Servilius Ahala with his own

hand slew Spurius Maelius when plotting a

revolution in the state. There was—there was

once such virtue in this republic, that brave

men would repress mischievous citizens with

severer chastisement than the most bitter enemy.

For we have a resolution (**) of the senate, a

formidable and authoritative decree against you,

O Catiline; the wisdom of the republic is not at

fault, nor the dignity of this senatorial body.

We, we alone,—I say it openly, —we, the consuls,

are waiting in our duty.

(*) This was Scipio Nasica, who called on the

consul Mucius Scaevola to do his duty and save

the republic; but as he refused to put any one

to death without a trial, Scipio called on all

the citizens to follow him, and stormed the

Capitol, which Gracchus had occupied with his

party, and slew many of the partisans of

Gracchus, and Gracchus himself.

(**) This resolution was couched in the form

Videant Consules nequid respublica detrimenti

capiat; and it exempted the consuls from all

obligation to attend to the ordinary forms of

law, and invested them with absolute power over

the lives of all the citizens who were

intriguing against the republic.

[4] The senate once passed a decree that Lucius

Opimius, the consul, should take care that the

republic suffered no injury. Not one night

elapsed. There was put to death, on some mere

suspicion of disaffection, Caius Gracchus, a man

whose family had borne the most unblemished

reputation for many generations. There was slain

Marcus Fulvius, a man of consular rank, and all

his children. By a like decree of the senate the

safety of the republic was entrusted to Caius

Marius and Lucius Valerius, the consuls. Did not

the vengeance of the republic, did not execution

overtake Lucius Saturninus, a tribune of the

people, and Caius Servilius, the praetor,

without the delay of one single day? But we, for

these twenty days have been allowing the edge of

the senate's authority to grow blunt, as it

were. For we are in possession of a similar

decree of the senate, but we keep it locked up

in its parchment—buried, I may say, in the

sheath; and according to this decree you ought,

O Catiline, to be put to death this instant. You

live,—and you live, not to lay aside, but to

persist in your audacity.

I wish, O conscript fathers, to be merciful; I

wish not to appear negligent amid such danger to

the state; but I do now accuse myself of

remissness and culpable inactivity.

[5] A camp is

pitched in Italy, at the entrance of Etruria, in

hostility to the republic; the number of the

enemy increases every day; and yet the general

of that camp, the leader of those enemies, we

see within the walls—yes, and even in the

senate, —planning every day some internal injury

to the republic. 1 If, O Catiline, I should now

order you to be arrested, to be put to death, I

should, I suppose, have to fear lest all good

men should say that I had acted tardily, rather

than that any one should affirm that I acted

cruelly. But yet this, which ought to have been

done long since, I have good reason for not

doing as yet; I will put you to death, then,

when there shall be not one person possible to

be found so wicked, so abandoned, so like

yourself, as not to allow that it has been

rightly done.

[6] As long as one

person exists who can dare to defend you, yet

shall live; but you shall live as you do now,

surrounded by my many and trusty guards, so that

you shall not be able to stir one finger against

the republic: many eyes and ears shall still

observe and watch you, as they have hitherto

done, though you shall not perceive them.

[7] Do you

recollect that on the 21st of October I said in

the senate, that on a certain day, which was to

be the 27th of October, C. Manlius, the

satellite and servant of your audacity, would be

in arms? Was I mistaken, Catiline, not only in

so important, so atrocious, so incredible a

fact, but, what is much more remarkable, hi the

very day? I said also in the senate that you had

fixed the massacre of the nobles for the 28th of

October, when many chief men of the senate had

left Rome, not so much for the sake of saving

themselves as of checking your designs. Can you

deny that on that very day you were so hemmed in

by my guards and my vigilance, that you were

unable to stir one finger against the republic;

when you said that you would be content with the

flight of the rest, and the slaughter of us who

remained?

[8] What? when you

made sure that you would be able to seize

Praeneste on the first of November by a

nocturnal attack, did you not find that that

colony was fortified by my order, by my

garrison, by my watchfulness and care? You do

nothing, you plan nothing, you think of nothing

which I not only do not hear, but which I do not

see and know every particular of.

[9] O ye immortal

gods, where on earth are we? in what city are we

living? what constitution is ours? There are

here,—here in our body, O conscript fathers, in

this the most holy and dignified assembly of the

whole world, men who meditate my death, and the

death of all of us, and the destruction of this

city, and of the whole world. I, the consul see

them; I ask them their opinion about the

republic, and I do not yet attack, even by

words, those who ought to be put to death by the

sword. You were, then, O Catiline, at Lecca's

that night; you divided Italy into sections; you

settled where every one was to go; you fixed

whom you were to leave at Rome, whom you were to

take with you; you portioned out the divisions

of the city for conflagration; you undertook

that you yourself would at once leave the city,

and said that there was then only this to delay

you, that I was still alive. Two Roman knights

were found to deliver you from this anxiety, and

to promise that very night, before daybreak, to

slay me in my bed.

[10] All this I

knew almost before your meeting had broken up. I

strengthened and fortified my house with a

stronger guard; I refused admittance, when they

came, to those whom you sent in the morning to

salute me, and of whom I had foretold to many

eminent men that they would come to me at that

time.

[11] Great thanks

are due to the immortal gods, and to this very

Jupiter Stator, in whose temple we are, the most

ancient protector of thus city, that we have

already so often escaped so foul, so horrible,

and so deadly an enemy to the republic. But the

safety of the commonwealth must not be too often

allowed to be risked on one man. As long as you,

O Catiline, plotted against me while I was the

consul elect, I defended myself not with a

public guard, but by my own private diligence.

When, in the next consular comitia, you wished

to slay me when I was actually consul, and your

competitors also, in the Campus Martius, I

checked your nefarious attempt by the assistance

and resources of my own friends, without

exciting any disturbance publicly. In short, as

often as you attacked me, I by myself opposed

you, and that, too, though I saw that my ruin

was connected with great disaster to the

republic.

[12] But now you

are openly attacking the entire republic. You

are summoning to destruction and devastation the

temples of the immortal gods, the houses of the

city, the lives of all the citizens; in short,

all Italy. Wherefore, since I do not yet venture

to do that which is the best thing, and which

belongs to my office and to the discipline of

our ancestors, I will do that which is more

merciful if we regard its rigour, and more

expedient for the state. For if I order you to

be put to death, the rest of the conspirators

will still remain in the republic; if as I have

long been exhorting you, you depart, your

companions, those worthless dregs of the

republic, will be drawn off from the city too.

[13] What is the

matter, Catiline? Do you hesitate to do that

which I order you which you were already doing

of your own accord? The consul orders an enemy

to depart from the city. Do you ask me, Are you

to go into banishment? I do not order it; but,

if you consult me, I advise it.

[14] What? when

lately by the death of your former wife you had

made your house empty and ready for a new

bridal, did you not even add another incredible

wickedness to this wickedness? But I pass that

over, and willingly allow it to be buried in

silence, that so horrible a crime may not be

seen to have existed in this city, and not to

have been chastised. I pass over the ruin of

your fortune, which you know is hanging over you

against the ides of the very next month; I come

to those things which relate not to the infamy

of your private vices, not to your domestic

difficulties and baseness, but to the welfare of

the republic and to the lives and safety of us

all.

[15] Can the limit

of this life, O Catiline, can the breath of this

atmosphere be pleasant to you, when you know

that there is not one man of those here present

who is ignorant that you, on the last day of the

year, when Lepidus and Tullus were consuls,

stood in the assembly armed; that you had

prepared your hand for the slaughter of the

consuls and chief men of the state, and that no

reason or fear of yours hindered your crime and

madness, but the fortune of the republic? And I

say no more of these things, for they are not

unknown to every one. How often have you

endeavoured to slay me, both as consul elect and

as actual consul? how many shots of yours, so

aimed that they seemed impossible to be escaped,

have I avoided by some slight stooping aside,

and some dodging, as it were, of my body? You

attempt nothing, you execute nothing, you devise

nothing that call be kept hid from me at the

proper time; and yet you do not cease to attempt

and to contrive.

[16] How often

already has that dagger of yours been wrested

from your hands? how often has it slipped

through them by some chance, and dropped down?

and yet you cannot any longer do without it; and

to what sacred mysteries it is consecrated and

devoted by you I know not, that you think it

necessary to plunge it in the body of the

consul.

[17] On my honour,

if my slaves feared me as all your

fellow-citizens fear you, I should think I must

leave my house. Do not you think you should

leave the city? If I saw that I was even

undeservedly so suspected and bated by my

fellow-citizens, I would rather flee from their

sight than be gazed at by the hostile eyes of

every one. And do you, who, from the

consciousness of your wickedness, know that the

hatred of all men is just and has been long due

to you, hesitate to avoid the sight and presence

of those men whose minds and senses you offend?

If your parents feared and hated you, and if you

could by no means pacify them, you would, I

think, depart somewhere out of their sight. Now,

your country, which is the common parent of all

of us, hates and fears you, and has no other

opinion of you, than that you are meditating

parricide in her case; and will you neither feel

awe of her authority, nor deference for her

judgment, nor fear of her power?

[18] And she, O

Catiline, thus pleads with you, and after a

manner silently speaks to you:—There has now for

many years been no crime committed but by you;

no atrocity has taken place without you; you

alone unpunished and unquestioned have murdered

the citizens, have harassed and plundered the

allies; you alone have had power not only to

neglect all laws and investigations, but to

overthrow and break through them. Your former

actions, though they ought not to have been

borne, yet I did bear as well as I could; but

now that I should be wholly occupied with fear

of you alone, that at every sound I should dread

Catiline, that no design should seem possible to

be entertained against me which does not proceed

from your wickedness, this is no longer

endurable. Depart, then, and deliver me from

this fear; that, if it be a just one, I may not

be destroyed; if an imaginary one, that at least

I may at last cease to fear.

[19] If, as I have

said, your country were thus to address you,

ought she not to obtain her request, even if she

were not able to enforce it? What shall I say of

your having given yourself into custody? what of

your having said, for the sake of avoiding

suspicion, that you were willing to dwell in the

house of Marcus Lepidus? And when you were not

received by him, you dared even to come to me,

and begged me to keep you in my house; and when

you had received answer from me that I could not

possibly be safe in the same house with you,

when I considered myself in great danger as long

as we were in the same city, you came to Quintus

Metellus, the praetor, and being rejected by

him, you passed on to your associate, that most

excellent man, Marcus Marcellus, who would be, I

suppose you thought, most diligent in guarding

you, most sagacious hi suspecting you, and most

bold in punishing you; but how far can we think

that man ought to be from bonds and imprisonment

who has already judged himself deserving of

being given into custody?

[20] Since, then,

this is the case, do you hesitate, O Catiline,

if you cannot remain here with tranquillity, to

depart to some distant laud, and to trust your

life, saved from just and deserved punishment,

to flight and solitude? Make a motion, say you,

to the senate, (for that is what you demand) and

if thus body votes that you ought to go into

banishment, you say that you will obey. I will

not make such a motion, it is contrary to my

principles, and yet I will let you see what

these men think of you. Be gone from the city, O

Catiline, deliver the republic from fear; depart

into banishment, if that is the word you are

waiting for. What now, O Catiline? Do you not

perceive, do you not see the silence of these

men; they permit it, they say nothing; why wait

you for the authority of their words when you

see their wishes in their silence?

[21] But had I

said the same to this excellent young man,

Publius Sextius, or to that brave man, Marcus

Marcellus, before this time the senate would

deservedly have laid violent hands on me, consul

though I be, in this very temple. But to you,

Catiline, while they are quiet they approve,

while they permit me to speak they vote, while

they are silent they are loud and eloquent. And

not they alone, whose authority forsooth is dear

to you, though their lives are unimportant, but

the Roman knights too, those most honourable and

excellent men, and the other virtuous citizens

who are now surrounding the senate, whose

numbers you could see, whose desires you could

know, and whose voices you a few minutes ago

could hear,—yes, whose very hands and weapons I

have for some time been scarcely able to keep

off from you; but those, too, I will easily

bring to attend you to the gates if you leave

these places you have been long desiring to lay

waste.

[22] And yet, why

am I speaking? that anything may change your

purpose? that you may ever amend your life? that

you may meditate flight or think of voluntary

banishment? I wish the gods may give you such a

mind; though I see, if alarmed at my words you

bring your mind to go into banishment, what a

storm of unpopularity hangs over me, if not at

present, while the memory of your wickedness is

fresh, at all events hereafter. But it is

worthwhile to incur that, as long as that is but

a private misfortune of my own, and is

unconnected with the dangers of the republic.

But we cannot expect that you should be

concerned at your own vices, that you should

fear the penalties of the laws, or that you

should yield to the necessities of the republic,

for you are not, O Catiline, one whom either

shame can recall from infamy, or fear from

danger, or reason from madness.

[23] Wherefore, as

I have said before, go forth, and if you to make

me, your enemy as you call me, unpopular, go

straight into banishment. I shall scarcely be

able to endue all that will be said if you do

so; I shall scarcely be able to support my load

of unpopularity if you do go into banishment at

the command of the consul; but if you wish serve

my credit and reputation, go forth with your

ill-omened band of profligates; betake yourself

to Manilius, rouse up the abandoned citizens,

separate yourself from the good ones, wage war

against your country, exult in your impious

banditti, so that you may not seem to have been

driven out by me and gone to strangers, but to

have gone invited to your own friends.

[24] Though why

should I invite you, by whom I know men have

been already sent on to wait in arms for you at

the forum Aurelium; who I know has fixed and

agreed with Manlius upon a settled day; by whom

I know that that silver eagle, which I trust

will be ruinous and fatal to you and to all your

friends, and to which there was set up in your

house a shrine as it were of your crimes, has

been already sent forward. Need I fear that you

can long do without that which you used to

worship when going out to do murder, and from

whose altars you have often transferred your

impious hand to the slaughter of citizens?

[25] You will go

at last where your unbridled and mad desire has

been long hurrying you. And this causes you no

grief; but an incredible pleasure. Nature has

formed you, desire has trained you, fortune has

preserved you for this insanity. Not only did

you never desire quiet, but you never even

desired any war but a criminal one; you have

collected a baud of profligates and worthless

men, abandoned not only by all fortune but even

by hope.

[26] Then what

happiness will you enjoy with what delight will

you exult in what pleasure will you revel! when

in so numerous a body of friends, you neither

hear nor see one good man. All the toils you

have gone through have always pointed to this

sort of life; your lying on the ground not

merely to lie in wait to gratify your unclean

desires, but even to accomplish crimes; your

vigilance, not only when plotting against the

sleep of husbands, but also against the goods of

your murdered victims, have all been

preparations for this. Now you have an

opportunity of displaying your splendid

endurance of hunger, of cold, of want of

everything; by which in a short time you will

find yourself worn out.

[27] All this I

effected when I procured your rejection from the

consulship, that you should be reduced to make

attempts on your country as an exile, instead of

being able to distress it as consul, and that

that which had been wickedly undertaken by you

should be called piracy rather than war.

[28] But even

private men have often in this republic slain

mischievous citizens.—Is it the laws which have

been passed about the punishment of Roman

citizens? But in this city those who have

rebelled against the republic have never had the

rights of citizens.—Do you fear odium with

posterity? You are showing fine gratitude to the

Roman people which has raised you, a man known

only by your own actions, of no ancestral

renown, through all the degrees of honour at so

early an age to the very highest office, if from

fear of unpopularity or of any danger you

neglect the safety of your fellow-citizens.

[29] But if you

have a fear of unpopularity, is that arising

from the imputation of vigour and boldness, or

that arising from that of inactivity and

indecision most to be feared? When Italy is laid

waste by war, when cities are attacked and

houses in flames, do you not think that you will

be then consumed by a perfect conflagration of

hatred?”

[30] Though there

are some men in this body who either do not see

what threatens, or dissemble what they do see;

who have fed the hope of Catiline by mild

sentiments, and have strengthened the rising

conspiracy by not believing it; influenced by

whose authority many, and they not wicked, but

only ignorant, if I punished him would say that

I had acted cruelly and tyranically. But I know

that if he arrives at the camp of Manlius to

which he is going, there will be no one so

stupid as not to see that there has been a

conspiracy; no one so hardened as not to confess

it. But if this man alone were put to death, I

know that this disease of the republic would be

only checked for awhile, not eradicated for

ever. But if he banishes himself; and takes with

him all his friends, and collects at one point

all the ruined men from every quarter, then not

only will this full-grown plague of the republic

be extinguished and eradicated, but also the

root and seed of all future evils.

[31] We have now

for a long time, O conscript fathers, lived

among these dangers and machinations of

conspiracy; but somehow or other, the ripeness

of all wickedness, and of this long-standing

madness and audacity, has come to a head at the

time of my consulship. But if this man alone is

removed from this piratical crew, we may appear,

perhaps, for a short time relieved from fear and

anxiety, but the danger will settle down and lie

hid in the veins and bowels of the republic. As

it often happens that men afflicted with a

severe disease, when they are tortured with heat

and fever, if they drink cold water, seem at

first to be relieved, but afterwards stiffer

more and more severely; so this disease which is

in the republic, if relieved by the punishment

of this man, will only get worse and worse, as

the rest will be still alive.

[32] Wherefore, O

conscript fathers, let the worthless be

gone,—let them separate themselves from the

good,—let them collect in one place,—let them,

as I have often said before, be separated from

us by a wall; let them cease to plot against the

consul in his own house,—to surround the

tribunal of the city praetor,—to besiege the

senate-house with swords,—to prepare brands and

torches to burn the city; let it, in short, be

written on the brow of every citizen, what are

his sentiments about the republic. I promise you

this, O conscript fathers, that there shall be

so much diligence in us the consuls, much

authority in you, so much virtue in the Roman

knights, so much unanimity in all good men, that

you shall see everything made plain and manifest

by the departure of Catiline,—everything checked

and punished.

[33] With these

omens, O Catiline, be gone to your impious and

nefarious war, to the great safety of the

republic, to your own misfortune and injury, and

to the destruction of those who have joined

themselves to you in every wickedness and

atrocity. Then do you, O Jupiter, who were

consecrated by Romulus with the same auspices as

this city, whom we rightly call the stay of this

city and empire, repel this man and his

companions from your altars and from the other

temples,—from the houses and walls of the

city,—from the lives and fortunes of all the

citizens; and overwhelm all the enemies of good

men, the foes of the republic, the robbers of

Italy, men bound together by a treaty and

infamous alliance of crimes, dead and alive,

with eternal punishments.

More History

|

|