|

NOT COMPLAINING OF THE PAST, SIMPLY

ASKING FOR A BETTER FUTURE

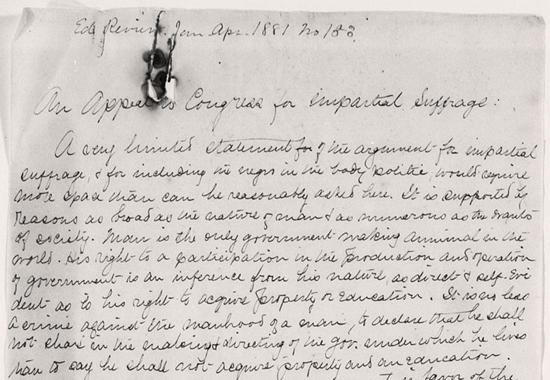

An Appeal to Congress for Impartial

Suffrage

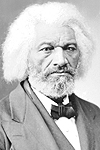

It follows the full text transcript of

Frederick Douglass' An Appeal to Congress for

Impartial Suffrage, as it was published in the

Atlantic Monthly 19 - January 1867.

|

A very limited

statement of the argument for impartial

suffrage, |

and for including

the negro in the body politic, would require

more space than can be reasonably asked here. It

is supported by reasons as broad as the nature

of man, and as numerous as the wants of society.

Man is the only government-making animal in the

world. His right to a participation in the

production and operation of government is an

inference from his nature, as direct and

self-evident as is his right to acquire property

or education. It is no less a crime against the

manhood of a man, to declare that he shall not

share in the making and directing of the

government under which he lives, than to say

that he shall not acquire property and

education.

The fundamental and unanswerable

argument in favor of the enfranchisement of the

negro is found in the undisputed fact of his

manhood. He is a man, and by every fact and

argument by which any man can sustain his right

to vote, the negro can sustain his right

equally. It is plain that, if the right belongs

to any, it belongs to all. The doctrine that

some men have no rights that others are bound to

respect, is a doctrine which we must banish as

we have banished slavery, from which it

emanated. If black men have no rights in the

eyes of white men, of course the whites can have

none in the eyes of the blacks. The result is a

war of races, and the annihilation of all proper

human relations.

But suffrage for the negro, while easily

sustained upon abstract principles, demands

consideration upon what are recognized as the

urgent necessities of the case. It is a measure

of relief,--a shield to break the force of a

blow already descending with violence, and

render it harmless. The work of destruction has

already been set in motion all over the South.

Peace to the country has literally meant war to

the loyal men of the South, white and black; and

negro suffrage is the measure to arrest and put

an end to that dreadful strife.

Something then, not by way of argument, (for

that has been done by Charles Sumner, Thaddeus

Stevens, Wendell Phillips, Gerrit Smith, and

other able men,) but rather of statement and

appeal.

For better or for worse, (as in some of the old

marriage ceremonies,) the negroes are evidently

a permanent part of the American population.

They are too numerous and useful to be

colonized, and too enduring and

self-perpetuating to disappear by natural

causes. Here they are, four millions of them,

and, for weal or for woe, here they must remain.

Their history is parallel to that of the

country; but while the history of the latter has

been cheerful and bright with blessings, theirs

has been heavy and dark with agonies and curses.

What O'Connell said of the history of Ireland

may with greater truth be said of the negro's.

It may be "traced like a wounded man through a

crowd, by the blood." Yet the negroes have

marvelously survived all the exterminating

forces of slavery, and have emerged at the end

of two hundred and fifty years of bondage, not

morose, misanthropic, and revengeful, but

cheerful, hopeful, and forgiving. They now stand

before Congress and the country, not complaining

of the past, but simply asking for a better

future. The spectacle of these dusky millions

thus imploring, not demanding, is touching; and

if American statesmen could be moved by a simple

appeal to the nobler elements of human nature,

if they had not fallen, seemingly, into the

incurable habit of weighing and measuring every

proposition of reform by some standard of profit

and loss, doing wrong from choice, and right

only from necessity or some urgent demand of

human selfishness, it would be enough to plead

for the negroes on the score of past services

and sufferings. But no such appeal shall be

relied on here. Hardships, services, sufferings,

and sacrifices are all waived.

It is true that

they came to the relief of the country at the

hour of its extremest need. It is true that, in

many of the rebellious States, they were almost

the only reliable friends the nation had

throughout the whole tremendous war. It is true

that, notwithstanding their alleged ignorance,

they were wiser than their masters, and knew

enough to be loyal, while those masters only

knew enough to be rebels and traitors. It is

true that they fought side by side in the loyal

cause with our gallant and patriotic white

soldiers, and that, but for their help,--divided

as the loyal States were,--the Rebels might have

succeeded in breaking up the Union, thereby

entailing border wars and troubles of unknown

duration and incalculable calamity. All this and

more is true of these loyal negroes. Many daring

exploits will be told to their credit. Impartial

history will paint them as men who deserved well

of their country. It will tell how they forded

and swam rivers, with what consummate address

they evaded the sharp-eyed Rebel pickets, how

they toiled in the darkness of night through the

tangled marshes of briers and thorns, barefooted

and weary, running the risk of losing their

lives, to warn our generals of Rebel schemes to

surprise and destroy our loyal army. It will

tell how these poor people, whose rights we

still despised, behaved to our wounded soldiers,

when found cold, hungry, and bleeding on the

deserted battle-field; how they assisted our

escaping prisoners from Andersonville, Belle

Isle, Castle Thunder, and elsewhere, sharing

with them their wretched crusts, and otherwise

affording them aid and comfort; how they

promptly responded to the trumpet call for their

services, fighting against a foe that denied

them the rights of civilized warfare, and for a

government which was without the courage to

assert those rights and avenge their violation

in their behalf; with what gallantry they flung

themselves upon Rebel fortifications, meeting

death as fearlessly as any other troops in the

service. But upon none of these things is

reliance placed. These facts speak to the better

dispositions of the human heart; but they seem

of little weight with the opponents of impartial

suffrage.

It is true that a strong plea for equal suffrage

might be addressed to the national sense of

honor. Something, too, might be said of national

gratitude. A nation might well hesitate before

the temptation to betray its allies. There is

something immeasurably mean, to say nothing of

the cruelty, in placing the loyal negroes of the

South under the political power of their Rebel

masters. To make peace with our enemies is all

well enough; but to prefer our enemies and

sacrifice our friends,--to exalt our enemies and

cast down our friends,--to clothe our enemies,

who sought the destruction of the government,

with all political power, and leave our friends

powerless in their hands,--is an act which need

not be characterized here. We asked the negroes

to espouse our cause, to be our friends, to

fight for us, and against their masters; and

now, after they have done all that we asked them

to do,--helped us to conquer their masters, and

thereby directed toward themselves the furious

hate of the vanquished,--it is proposed in some

quarters to turn them over to the political

control of the common enemy of the government

and of the negro. But of this let nothing be

said in this place. Waiving humanity, national

honor, the claims of gratitude, the precious

satisfaction arising from deeds of charity and

justice to the weak and defenseless,--the appeal

for impartial suffrage addresses itself with

great pertinence to the darkest, coldest, and

flintiest side of the human heart, and would

wring righteousness from the unfeeling

calculations of human selfishness.

For in respect to this grand measure it is the

good fortune of the negro that enlightened

selfishness, not less than justice, fights on

his side. National interest and national duty,

if elsewhere separated, are firmly united here.

The American people can, perhaps, afford to

brave the censure of surrounding nations for the

manifest injustice and meanness of excluding its

faithful black soldiers from the ballot-box, but

it cannot afford to allow the moral and mental

energies of rapidly increasing millions to be

consigned to hopeless degradation.

Strong as we are, we need the energy that

slumbers in the black man's arm to make us

stronger. We want no longer any heavy- footed,

melancholy service from the negro. We want the

cheerful activity of the quickened manhood of

these sable millions. Nor can we afford to

endure the moral blight which the existence of a

degraded and hated class must necessarily

inflict upon any people among whom such a class

may exist. Exclude the negroes as a class from

political rights,--teach them that the high and

manly privilege of suffrage is to be enjoyed by

white citizens only,-- that they may bear the

burdens of the state, but that they are to have

no part in its direction or its honors,--and you

at once deprive them of one of the main

incentives to manly character and patriotic

devotion to the interests of the government; in

a word, you stamp them as a degraded caste,--you

teach them to despise themselves, and all others

to despise them.

Men are so constituted that

they largely derive their ideas of their

abilities and their possibilities from the

settled judgments of their fellow-men, and

especially from such as they read in the

institutions under which they live. If these

bless them, they are blest indeed; but if these

blast them, they are blasted indeed. Give the

negro the elective franchise, and you give him

at once a powerful motive for all noble

exertion, and make him a man among men. A

character is demanded of him, and here as

elsewhere demand favors supply. It is nothing

against this reasoning that all men who vote are

not good men or good citizens. It is enough that

the possession and exercise of the elective

franchise is in itself an appeal to the nobler

elements of manhood, and imposes education as

essential to the safety of society.

To appreciate the full force of this argument,

it must be observed, that disfranchisement in a

republican government based upon the idea of

human equality and universal suffrage, is a very

different thing from disfranchisement in

governments based upon the idea of the divine

right of kings, or the entire subjugation of the

masses. Masses of men can take care of

themselves. Besides, the disabilities imposed

upon all are necessarily without that bitter and

stinging element of invidiousness which attaches

to disfranchisement in a republic. What is

common to all works no special sense of

degradation to any. But in a country like ours,

where men of all nations, kindred, and tongues

are freely enfranchised, and allowed to vote, to

say to the negro, You shall not vote, is to deal

his manhood a staggering blow, and to burn into

his soul a bitter and goading sense of wrong, or

else work in him a stupid indifference to all

the elements of a manly character. As a nation,

we cannot afford to have amongst us either this

indifference and stupidity, or that burning

sense of wrong. These sable millions are too

powerful to be allowed to remain either

indifferent or discontented. Enfranchise them,

and they become self-respecting and

country-loving citizens. Disfranchise them, and

the mark of Cain is set upon them less

mercifully than upon the first murderer, for no

man was to hurt him. But this mark of

inferiority--all the more palpable because of a

difference of color--not only dooms the negro to

be a vagabond, but makes him the prey of insult

and outrage everywhere. While nothing may be

urged here as to the past services of the negro,

it is quite within the line of this appeal to

remind the nation of the possibility that a time

may come when the services of the negro may be a

second time required. History is said to repeat

itself, and, if so, having wanted the negro

once, we may want him again. Can that

statesmanship be wise which would leave the

negro good ground to hesitate, when the

exigencies of the country required his prompt

assistance? Can that be sound statesmanship

which leaves millions of men in gloomy

discontent, and possibly in a state of

alienation in the day of national trouble? Was

not the nation stronger when two hundred

thousand sable soldiers were hurled against the

Rebel fortifications, than it would have been

without them? Arming the negro was an urgent

military necessity three years ago,--are we sure

that another quite as pressing may not await us?

Casting aside all thought of justice and

magnanimity, is it wise to impose upon the negro

all the burdens involved in sustaining

government against foes within and foes without,

to make him equal sharer in all sacrifices for

the public good, to tax him in peace and

conscript him in war, and then coldly exclude

him from the ballot-box?

Look across the sea. Is Ireland, in her present

condition, fretful, discontented, compelled to

support an establishment in which she does not

believe, and which the vast majority of her

people abhor, a source of power or of weakness

to Great Britain? Is not Austria wise in

removing all ground of complaint against her on

the part of Hungary? And does not the Emperor of

Russia act wisely, as well as generously, when

he not only breaks up the bondage of the serf,

but extends him all the advantages of Russian

citizenship? Is the present movement in England

in favor of manhood suffrage--for the purpose of

bringing four millions of British subjects into

full sympathy and co-operation with the British

government--a wise and humane movement, or

otherwise? Is the existence of a rebellious

element in our borders--which New Orleans,

Memphis, and Texas show to be only disarmed, but

at heart as malignant as ever, only waiting for

an opportunity to reassert itself with fire and

sword--a reason for leaving four millions of the

nation's truest friends with just cause of

complaint against the Federal government? If the

doctrine that taxation should go hand in hand

with representation can be appealed to in behalf

of recent traitors and rebels, may it not

properly be asserted in behalf of a people who

have ever been loyal and faithful to the

government? The answers to these questions are

too obvious to require statement.

Disguise it as

we may, we are still a divided nation. The Rebel

States have still an anti-national policy.

Massachusetts and South Carolina may draw tears

from the eyes of our tender-hearted President by

walking arm in arm into his Philadelphia

Convention, but a citizen of Massachusetts is

still an alien in the Palmetto State. There is

that, all over the South, which frightens Yankee

industry, capital, and skill from its borders.

We have crushed the Rebellion, but not its hopes

or its malign purposes. The South fought for

perfect and permanent control over the Southern

laborer. It was a war of the rich against the

poor. They who waged it had no objection to the

government, while they could use it as a means

of confirming their power over the laborer. They

fought the government, not because they hated

the government as such, but because they found

it, as they thought, in the way between them and

their one grand purpose of rendering permanent

and indestructible their authority and power

over the Southern laborer. Though the battle is

for the present lost, the hope of gaining this

object still exists, and pervades the whole

South with a feverish excitement. We have thus

far only gained a Union without unity, marriage

without love, victory without peace. The hope of

gaining by politics what they lost by the sword,

is the secret of all this Southern unrest; and

that hope must be extinguished before national

ideas and objects can take full possession of

the Southern mind. There is but one safe and

constitutional way to banish that mischievous

hope from the South, and that is by lifting the

laborer beyond the unfriendly political designs

of his former master. Give the negro the

elective franchise, and you at once destroy the

purely sectional policy, and wheel the Southern

States into line with national interests and

national objects. The last and shrewdest turn of

Southern politics is a recognition of the

necessity of getting into Congress immediately,

and at any price. The South will comply with any

conditions but suffrage for the negro. It will

swallow all the unconstitutional test oaths,

repeal all the ordinances of Secession,

repudiate the Rebel debt, promise to pay the

debt incurred in conquering its people, pass all

the constitutional amendments, if only it can

have the negro left under its political control.

The proposition is as modest as that made on the

mountain: "All these things will I give unto

thee if thou wilt fall down and worship me."

But why are the Southerners so willing to make

these sacrifices? The answer plainly is, they

see in this policy the only hope of saving

something of their old sectional peculiarities

and power. Once firmly seated in Congress, their

alliance with Northern Democrats re-established,

their States restored to their former position

inside the Union, they can easily find means of

keeping the Federal government entirely too busy

with other important matters to pay much

attention to the local affairs of the Southern

States. Under the potent shield of State Rights,

the game would be in their own hands. Does any

sane man doubt for a moment that the men who

followed Jefferson Davis through the late

terrible Rebellion, often marching barefooted

and hungry, naked and penniless, and who now

only profess an enforced loyalty, would plunge

this country into a foreign war to-day, if they

could thereby gain their coveted independence,

and their still more coveted mastery over the

negroes? Plainly enough, the peace not less than

the prosperity of this country is involved in

the great measure of impartial suffrage. King

Cotton is deposed, but only deposed, and is

ready to-day to reassert all his ancient

pretensions upon the first favorable

opportunity. Foreign countries abound with his

agents. They are able, vigilant, devoted. The

young men of the South burn with the desire to

regain what they call the lost cause; the women

are noisily malignant towards the Federal

government. In fact, all the elements of treason

and rebellion are there under the thinnest

disguise which necessity can impose.

What, then, is the work before Congress? It is

to save the people of the South from themselves,

and the nation from detriment on their account.

Congress must supplant the evident sectional

tendencies of the South by national dispositions

and tendencies. It must cause national ideas and

objects to take the lead and control the

politics of those States. It must cease to

recognize the old slave-masters as the only

competent persons to rule the South. In a word,

it must enfranchise the negro, and by means of

the loyal negroes and the loyal white men of the

South build up a national party there, and in

time bridge the chasm between North and South,

so that our country may have a common liberty

and a common civilization. The new wine must be

put into new bottles. The lamb may not be

trusted with the wolf. Loyalty is hardly safe

with traitors.

Statesmen of America! beware what you do. The

ploughshare of rebellion has gone through the

land beam-deep. The soil is in readiness, and

the seed-time has come. Nations, not less than

individuals, reap as they sow. The dreadful

calamities of the past few years came not by

accident, nor unbidden, from the ground. You

shudder to-day at the harvest of blood sown in

the spring-time of the Republic by your patriot

fathers. The principle of slavery, which they

tolerated under the erroneous impression that it

would soon die out, became at last the dominant

principle and power at the South. It early

mastered the Constitution, became superior to

the Union, and enthroned itself above the law.

Freedom of speech and of the press it slowly but

successfully banished from the South, dictated

its own code of honor and manners to the nation,

brandished the bludgeon and the bowie-knife over

Congressional debate, sapped the foundations of

loyalty, dried up the springs of patriotism,

blotted out the testimonies of the fathers

against oppression, padlocked the pulpit,

expelled liberty from its literature, invented

nonsensical theories about master-races and

slave-races of men, and in due season produced a

Rebellion fierce, foul, and bloody.

This evil principle again seeks admission into

our body politic. It comes now in shape of a

denial of political rights to four million loyal

colored people. The South does not now ask for

slavery. It only asks for a large degraded

caste, which shall have no political rights.

This ends the case. Statesmen, beware what you

do. The destiny of unborn and unnumbered

generations is in your hands. Will you repeat

the mistake of your fathers, who sinned

ignorantly? or will you profit by the

blood-bought wisdom all round you, and forever

expel every vestige of the old abomination from

our national borders? As you members of the

Thirty-ninth Congress decide, will the country

be peaceful, united, and happy, or troubled,

divided, and miserable.

More History

|

|