|

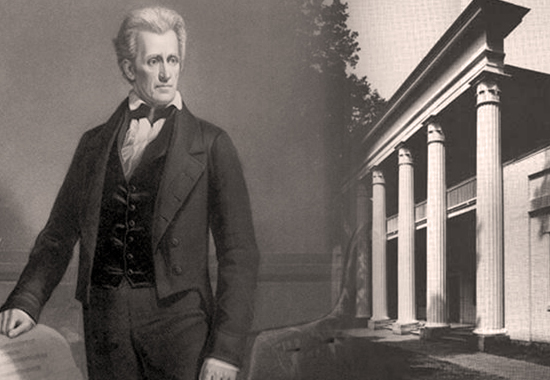

JACKSON READY TO RETIRE AT HIS HOME,

THE HERMITAGE, NASHVILLE, TN

President Andrew Jackson's Farewell

Address

Go here for more about

Andrew Jackson.

Andrew Jackson.

Go here for more about

Andrew Jackson's Farewell Address.

Andrew Jackson's Farewell Address.

It follows the full text transcript of

Andrew Jackson's Farewell Address, also called

A Political Testament,

delivered at Washington D.C. - March 4, 1837.

|

Fellow Citizens, |

Being about to

retire finally from public life, I beg leave to

offer you my grateful thanks for the many proofs

of kindness and confidence which I have received

at your hands. It has been my fortune, in the

discharge of public duties, civil and military,

frequently to have found myself in difficult and

trying situations where prompt decision and

energetic action were necessary and where the

interest of the country required that high

responsibilities should be fearlessly

encountered; and it is with the deepest emotions

of gratitude that I acknowledge the continued

and unbroken confidence with which you have

sustained me in every trial. My public life has

been a long one, and I cannot hope that it has,

at all times, been free from errors. But I have

the consolation of knowing that, if mistakes

have been committed, they have not seriously

injured the country I so anxiously endeavored to

serve; and, at the moment when I surrender my

last public trust, I leave this great people

prosperous and happy; in the full enjoyment of

liberty and peace; and honored and respected by

every nation of the world.

If my humble efforts have, in any degree,

contributed to preserve to you these blessings,

I have been more than rewarded by the honors you

have heaped upon me; and, above all, by the

generous confidence with which you have

supported me in every peril, and with which you

have continued to animate and cheer my path to

the closing hour . of my political life. The

time has now come when advanced age and a broken

frame warn me to retire from public concerns;

but the recollection of the many favors you have

bestowed upon me is engraven upon my heart, and

I have felt that I could not part from your

service without making this public

acknowledgment of the gratitude I owe you. And

if I use the occasion to offer to you the

counsels of age and experience, you will, I

trust, receive them with the same indulgent

kindness which you have so often extended to me;

and will, at least, see in them an earnest

desire to perpetuate, in this favored land, the

blessings of liberty and equal laws.

We have now lived

almost fifty years under the Constitution framed

by the sages and patriots of the Revolution. The

conflicts in which the nations of Europe were

engaged during a great part of this period; the

spirit in which they waged war against each

other; and our intimate commercial connections

with every part of the civilized world, rendered

it a time of much difficulty for the Government

of the United States. We have had our seasons of

peace and of war, with all the evils which

precede or follow a state of hostility with

powerful nations. We encountered these trials

with our Constitution yet in its infancy, and

under the disadvantages which a new and untried

Government must always feel when it is called

upon to put forth its whole strength, without

the lights of experience to guide it or the

weight of precedents to justify its measures.

But we have passed triumphantly through all

these difficulties. Our Constitution is no

longer a doubtful experiment; and, at the end of

nearly half a century, we find that it has

preserved unimpaired the liberties of the

people, secured the rights of property, and that

our country has improved and is flourishing

beyond any former example in the history of

nations.

In our domestic concerns there is everything to

encourage us; and if you are true to yourselves,

nothing can impede your march to the highest

point of national prosperity. The States which

had so long been retarded in their improvement

by the Indian tribes residing in the midst of

them are at length relieved from the evil; and

this unhappy race - the original dwellers in our

land - are now placed in a situation where we

may well hope that they will share in the

blessings of civilization and be saved from that

degradation and destruction to which they were

rapidly hastening while they remained in the

States; and while the safety and comfort of our

own citizens have been greatly promoted by their

removal, the philanthropist will rejoice that

the remnant of that ill-fated race has been at

length placed beyond the reach of injury or

oppression, and that the paternal care of the

General Government will hereafter watch over

them and protect them.

If we turn to our relations with foreign powers,

we find our condition equally gratifying.

Actuated by the sincere desire to do justice to

every nation and to preserve the blessings of

peace, our intercourse with them has been

conducted on the part of this Government in the

spirit of frankness, and I take pleasure in

saying that it has generally been met in a

corresponding temper. Difficulties of old

standing have been surmounted by friendly

discussion and the mutual desire to be just; and

the claims of our citizens, which had been long

withheld, have at length been acknowledged and

adjusted, and satisfactory arrangements made for

their final payment; and with a limited and, I

trust, a temporary exception, our relations with

every foreign power are now of the most friendly

character, our commerce continually expanding,

and our flag respected in every quarter of the

world.

These cheering and

grateful prospects and these multiplied favors

we owe, under Providence, to the adoption of the

Federal Constitution. It is no longer a question

whether this great country can remain happily

united and flourish under our present form of

government. Experience, the unerring test of all

human undertakings, has shown the wisdom and

foresight of those who formed it; and has proved

that in the union of these States there is a

sure foundation for the brightest hopes of

freedom and for the happiness of the people. At

every hazard and by every sacrifice, this Union

must be preserved.

The necessity of watching with jealous anxiety

for the preservation of the Union was earnestly

pressed upon his fellow citizens by the Father

of his country in his farewell address. He has

there told us, that "while experience shall not

have demonstrated its impracticability, there

will always be reason to distrust the patriotism

of those who, in any quarter, may endeavor to

weaken its bonds"; and he has cautioned us, in

the strongest terms, against the formation of

parties on geographical discriminations, as one

of the means which might disturb our union, and

to which designing men would be likely to the

resort.

The lessons contained in this invaluable legacy

of Washington to his countrymen should be

cherished in the heart of every citizen to the

latest generation; and, perhaps, at no period of

time could they be more usefully remembered than

at the present moment. For when we look upon the

scenes that are passing around us, and dwell

upon the pages of his parting address, his

paternal counsels would seem to be not merely

the offspring of wisdom and foresight, but the

voice of prophecy foretelling events and warning

us of the evil to come. Forty years have passed

since this imperishable document was given to

his countrymen. The Federal Constitution was

then regarded by him as an experiment, and he so

speaks of it in his address; but an experiment

upon the success of which the best hopes of his

country depended, and we all know that he was

prepared to lay down his life, if necessary, to

secure to it a full and a fair trial. The trial

has been made. It has succeeded beyond the

proudest hopes of those who framed it. Every

quarter of this widely extended nation has felt

its blessings and shared in the general

prosperity produced by its adoption. But amid

this general prosperity and splendid success,

the dangers of which he warned us are becoming

every day more evident and the signs of evil are

sufficiently apparent to awaken the deepest

anxiety in the bosom of the patriot. We behold

systematic efforts publicly made to sow the

seeds of discord between different parts of the

United States and to place party divisions

directly upon geographical distinctions; to

excite the south against the north and the north

against the south; and to force into the

controversy the most delicate and exciting

topics, topics upon which it is impossible that

a large portion of the Union can ever speak

without strong emotion. Appeals, too, are

constantly made to sectional interests in order

to influence the election of the Chief

Magistrate, as if it were desired that he should

favor a particular quarter of the country

instead of fulfilling the duties of his station

with impartial justice to all; and the possible

dissolution of the Union has at length become an

ordinary and familiar subject of discussion. Has

the warning voice of Washington been forgotten?

or have designs already been formed to sever the

Union? Let it not be supposed that I impute to

all of those who have taken an active part in

these unwise and unprofitable discussions a want

of patriotism or of public virtue. The honorable

feeling of State pride and local attachments

find a place in the bosoms of the most

enlightened and pure. But while such men are

conscious of their own integrity and honesty of

purpose, they ought never to forget that the

citizens of other States are their political

brethren; and that, however mistaken they may be

in their views, the great body of them are

equally honest and upright with themselves.

Mutual suspicions and reproaches may in time

create mutual hostility, and artful and

designing men will always be found, who are

ready to to foment these fatal divisions and to

inflame the natural jealousies of different

sections of the country. The history of the

world is full of such examples and especially

the history of republics.

What have you to gain by division and

dissension? Delude not yourselves with the

belief that a breach once made may be after

wards repaired. If the Union is once severed,

the line of separation will grow wider and

wider, and the controversies which are now

debated and settled in the halls of legislation

will then be tried in fields of battle and

determined by the sword. Neither should you

deceive yourselves with the hope that the first

line of separation would be the permanent one,

and that nothing but harmony and concord would

be found in the new associations formed upon the

dissolution of this Union. Local interests would

still be found there, and unchastened ambition.

And if the recollection of common dangers in

which the people of these United States stood

side by side against the common foe; the memory

of victories won by their united valor; the

prosperity and happiness they have enjoyed under

the present Constitution; the proud name they

bear as citizens of this great republic; if all

these recollections and proofs of common

interest are not strong enough to bind us

together as one people, what tie will hold

united the new divisions of empire, when these

bonds have been broken and this Union

dissevered? The first line of separation would

not last for a single generation; new fragments

would be torn off; new leaders would spring up;

and this great and glorious republic would soon

be broken into a multitude of petty states,

without commerce, without credit; jealous of one

another; armed for mutual aggression; loaded

with taxes to pay armies and leaders; seeking

aid against each other from foreign powers;

insulted and trampled upon by the nations of

Europe, until, harassed with conflicts and

humbled and debased in I spirit, they would be

ready to submit to the absolute dominion of any

military adventurer and to surrender their

liberty for the sake of repose. It is impossible

to look on the consequences that would

inevitably follow the destruction of this

Government and not feel indignant when we hear

cold calculations about the value of the Union

and have so constantly before us a line of

conduct so well calculated to weaken its ties.

There is too much at stake to allow pride or

passion to influence unless he clearly saw that

the time had come when a freeman should prefer

death to submission; for if such a struggle is

once begun and the citizens of any State or

States can deliberately intend to do wrong. They

may, under the influence of temporary excitement

or misguided opinions, commit mistakes; they may

be misled for a time by the suggestions of

self-interest; but in a community so enlightened

and patriotic as the people of the United

States, argument will soon make them sensible of

their errors; and, when convinced, they will be

ready to repair them. If they have no higher or

better motives to govern them, they will at

least perceive that their own interest requires

them to be just to others as they hope to

receive justice at their hands.

But in order to

maintain the Union unimpaired, it is absolutely

necessary that the laws passed by the

constituted authorities should be faithfully

executed in every part of the country, and that

every good citizen should, at all times, stand

ready to put down, with the combined force of

the nation, every attempt at unlawful

resistance, under whatever pretext it may be

made or whatever shape it may assume.

Unconstitutional or oppressive laws may no doubt

be passed by Congress, either from erroneous

views or the want of due consideration; if they

are within the reach of judicial authority, the

remedy is easy and peaceful; and if, from the

character of the law, it is an abuse of power

not within the control of the judiciary, then

free discussion and calm appeals to reason and

to the justice of the people will not fail to

redress the wrong. But until the law shall be

declared void by the courts or repealed by

Congress, no individual or combination of

individuals can be justified in forcibly

resisting its execution. It is impossible that

any Government can continue to exist upon any

other principles. It would cease to be a

Government and be unworthy of the name if it had

not the power to enforce the execution of its

own laws within its own sphere of action.

It is true that cases may be imagined disclosing

such a settled purpose of usurpation and

oppression on the part of the Government as

would justify an appeal to arms. These, however,

are extreme cases, which we have no reason to

apprehend in a Government where the power is in

the hands of a patriotic people; and no citizen

who loves his country would in any case whatever

resort to forcible resistance, unless he clearly

saw that the time had come when a freeman should

prefer death to submission; for if such a

struggle is once begun and the citizens of one

section of the country arrayed in arms against

those of another in doubtful conflict, let the

battle result as it may, there will be an end of

the Union and, with it, an end to the hopes of

freedom. The victory of the injured would not

secure to them the blessings of liberty; it

would avenge their wrongs, but they would

themselves share in the common ruin.

But the Constitution cannot be maintained nor

the Union preserved in opposition to public

feeling by the mere exertion of the coercive

powers confided to the General Government. The

foundations must be laid in the affections of

the people; in the security it gives to life,

liberty, character, and property, in every

quarter of the country; and in the fraternal

attachment which the citizens of the several

States bear to one another as members of one

political family, mutually contributing to

promote the happiness of each other. Hence the

citizens of every State should studiously avoid

everything calculated to wound the sensibility

or offend the just pride of the people of other

States; and they should frown upon any

proceedings within their own borders likely to

disturb the tranquility of their political

brethren in other portions of the Union. In a

country so extensive as the United States and

with pursuits so varied, the internal

regulations of the several States must

frequently differ from one another in important

particulars; and this difference is unavoidably

increased by the varying principles upon which

the American colonies were originally planted;

principles which had taken deep root in their

social relations before the Revolution, and,

therefore, of necessity influencing their policy

since they became free and independent States.

But each State has the unquestionable right to

regulate its own internal concerns according to

its own pleasure; and while it does not

interfere; with the rights of the people of

other States or the rights of the Union, every

State must be the sole judge of the measures

proper to secure the safety of its citizens and

promote their happiness; and all efforts on the

part of people of other States to cast odium

upon their institutions, and all measures

calculated to disturb their rights of property

or to put in jeopardy their peace and internal

tranquility are in direct opposition to the

spirit in which the Union was formed, and must

endanger its safety. Motives of philanthropy may

be assigned for this unwarrantable interference;

and weak men may persuade them selves for a

moment that they are laboring in the cause of

humanity and asserting the rights of the human

race; but everyone, upon sober reflection, will

see that nothing but mischief can come from

these improper assaults upon the feelings and

rights of others. Rest assured that the men

found busy in this work of discord are not

worthy of your confidence and deserve your

strongest reprobation.

In the legislation of Congress, also, and in

every measure of the General Government, justice

to every portion of the United States should be

faithfully observed. No free Government can

stand without virtue in the people, and a lofty

spirit of patriotism; and if the sordid feelings

of mere selfishness shall usurp the place which

ought to be filled by public spirit, the

legislation of Congress will soon be converted

into a scramble for personal and sectional

advantages. Under our free institutions, the

citizens of every quarter of our country are

capable of attaining a high degree of prosperity

and happiness without seeking to profit

themselves at the expense of others; and every

such attempt must in the end fail to succeed,

for the people in every part of the United

States are too enlightened not to understand

their own rights and interests and to detect and

defeat every effort to gain undue advantages

over them; and when such designs are discovered,

it naturally provokes resentments which cannot

always be easily allayed. Justice, full and

ample justice, to every portion of the United

States should be the ruling principle of every

freeman and should guide the deliberations of

every public body, whether it be State or

national.

It is well known

that there have always been those amongst us who

wish to enlarge the powers of the General

Government; and experience would seem to

indicate that there is a tendency on the part of

this Government to overstep the boundaries

marked out for it by the Constitution. Its

legitimate authority is abundantly sufficient

for all the purposes for which it was created;

and its powers being expressly enumerated, there

can be no justification for claiming anything

beyond them. Every attempt to exercise power

beyond these limits should be promptly and

firmly opposed. For one evil example will lead

to other measures still more mischievous; and if

the principle of constructive powers, or

supposed advantages, or temporary circumstances,

shall ever be permitted to justify the

assumption of a power not given by the

Constitution, the General Government will before

long absorb all the powers of legislation, and

you will have, in effect, but one consolidated

Government. From the extent of our country, its

diversified interests, different pursuits, and

different habits, it is too obvious for argument

that a single consolidated Government would be

wholly inadequate to watch over and protect its

interests; and every friend of our free

institutions should be always prepared to

maintain unimpaired and in full vigor the rights

and sovereignty of the States and to confine the

action of the General Government strictly to the

sphere of its appropriate duties.

There is, perhaps, no one of the powers

conferred on the Federal Government so liable to

abuse as the taxing power. The most productive

and convenient sources of revenue were

necessarily given to it, that it might be able

to perform the important duties imposed upon it;

and the taxes which it lays upon commerce being

concealed from the real payer in the price of

the article, they do not so readily attract the

attention of the people as smaller sums demanded

from them directly by the tax gatherer. But the

tax imposed on goods enhances by so much the

price of the commodity to the consumer, and, as

many of these duties are imposed on articles of

necessity which are daily used by the great body

of the people, the money raised by these imposts

is drawn from their pockets. Congress has no

right, under the Constitution, to take money

from the people unless it is required to execute

some one of the specific powers intrusted Ťo the

Government; and if they raise more than is

necessary for such purposes, it is an abuse of

the power of taxation and unjust and I

oppressive. It may, indeed, happen that the

revenue will sometimes exceed the amount

anticipated when the taxes were laid. When,

however, this is ascertained, it is easy to

reduce them; and, in such a case, it is

unquestionably the duty of the Government to

reduce them, for no circumstances can justify it

in assuming a power not given to it by the

Constitution nor in taking away the money of the

people when it is not needed for the legitimate

wants of the Government.

Plain as these principles appear to be, you will

yet find that there is a constant effort to

induce the General Government to go beyond the

limits of its taxing power and to impose

unnecessary burdens upon the people. Many

powerful interests are continually at work to

procure heavy duties on commerce and to swell

the revenue beyond the real necessities of the

public service; and the country has already felt

the injurious effects of their combined

influence. They succeeded in obtaining a tariff

of duties bearing most oppressively on the

agricultural and laboring classes of society and

producing a revenue that could not be usefully

employed within the range of the powers

conferred upon Congress; and, in order to fasten

upon the people this unjust and unequal system

of taxation, extravagant schemes of internal

improvement were got up in various quarters to

squander the money and to purchase support.

Thus, one unconstitutional measure was intended

to be upheld by another, and the abuse of the

power of taxation was to be maintained by

usurping the power of expending the money in

internal improvements. You cannot have forgotten

the severe and doubtful struggle through which

we passed When the Executive Department of the

Government, by its veto, endeavored to arrest

this prodigal scheme of injustice, and to bring

back the legislation of Congress to the

boundaries prescribed by the Constitution. The

good sense and practical judgment of the people,

when the subject was brought before them,

sustained the course of the Executive; and this

plan of unconstitutional expenditure for the

purpose of corrupt influence is, I trust,

finally overthrown.

The result of this decision has been felt in the

rapid extinguishment of the public debt and the

large accumulation of a surplus in the treasury,

notwithstanding the tariff was reduced and is

now very far below the amount originally

contemplated by its advocates. But, rely upon

it, the design to collect an extravagant revenue

and to burden you with taxes beyond the

economical wants of the Government is not yet

abandoned. The various interests which have

combined together to impose a heavy tariff and

to produce an overflowing treasury are too

strong and have too much at stake to surrender

the contest. The corporations and wealthy

individuals who are engaged in large

manufacturing establishments desire a high

tariff to increase their gains. Designing

politicians will support it to conciliate their

favor and to obtain the means of profuse

expenditure for the purpose of purchasing

influence in other quarters; and since the

people have decided that the Federal Government

cannot be permitted to employ its income in

internal improvements, efforts will be made to

seduce and mislead the citizens of the several

States by holding out to them the deceitful

prospect of benefits to be derived from a

surplus revenue collected by the General

Government and annually divided among the

States. And if, encouraged by these fallacious

hopes, the States should disregard the

principles of economy which ought to

characterize every republican Government and

should indulge in lavish expenditures exceeding

their resources, they will, before long, find

themselves oppressed with debts which they are

unable to pay, and the temptation will become

irresistible to support a high tariff in order

to obtain a surplus for distribution. Do not

allow yourselves, my fellow citizens, to be

misled on this subject. The Federal Government

cannot collect a surplus for such purposes

without violating the principles of the

Constitution and assuming powers which have not

been granted. It is, moreover, a system of

injustice, and, if persisted in, will inevitably

lead to corruption and must end in ruin. The

surplus revenue will be drawn from the pockets

of the people, from the farmer, the mechanic,

and the laboring classes of society; but who

will receive it when distributed among the

States, where it is to be disposed of by leading

State politicians who have friends to favor and

political partisans to gratify? It will

certainly not be returned to those who paid it

and who have most need of it and are honestly

entitled to it. There is but one safe rule, and

that is to confine the General Government

rigidly within the sphere of its appropriate

duties. It has no power to raise a revenue or

impose taxes except for the purposes enumerated

in the Constitution; and if its income is found

to exceed these wants, it should be forthwith

reduced, and the burdens of the people so far

lightened.

In reviewing the

conflicts which have taken place between

different interests in the United States and the

policy pursued since the adoption of our present

form of government, we find nothing that has

produced such deep-seated evil as the course of

legislation in relation to the currency. The

Constitution of the United States unquestionably

intended to secure to the people a circulating

medium of gold and silver. But the establishment

of a national bank by Congress with the

privilege of issuing paper money receivable m

the payment of the public dues, and the

unfortunate course of legislation in the several

States upon the same subject, drove from general

circulation the constitutional currency and

substituted one of paper in its place.

It was not easy for men engaged in the ordinary

pursuits of business, whose attention had not

been particularly drawn to the subject, to

foresee all the consequences of a currency

exclusively of paper; and we ought not, on that

account, to be surprised at the facility with

which laws were obtained to carry into effect

the paper system. Honest and even enlightened

men are sometimes misled by the specious and

plausible statements of the designing. But

experience has now proved the mischiefs and

dangers of a paper currency, and it rests with

you to determine whether the proper remedy shall

be applied.

The paper system being founded on public

confidence and having of itself no intrinsic

value, it is liable to great and sudden

fluctuations; thereby rendering property

insecure and the wages of labor unsteady and

uncertain. The corporations which create the

paper money can- not be relied upon to keep the

circulating medium uniform in amount. In times

of prosperity when confidence is high, they are

tempted by the prospect of gain, or by the

influence of those who hope to profit by it to

extend their issues of paper beyond the bounds

of discretion and the reasonable demands of

business. And when these issues have been pushed

on from day to day until public confidence is at

length shaken, then a reaction takes place, and

they immediately withdraw the credits they have

given; suddenly curtail their issues; and

produce an unexpected and ruinous contraction of

the circulating medium which is felt by the

whole community. The banks by this means save

themselves, and the mischievous consequences of

their imprudence or cupidity are visited upon

the public. Nor does the evil stop here. These

ebbs and flows in the currency and these

indiscreet extensions of credit naturally

engender a spirit of speculation injurious to

the habits and character of the people. We have

already seen its effects in the wild spirit of

speculation in the public lands and various

kinds of stock which, within the last year or

two, seized upon such a multitude of our

citizens and threatened to pervade all classes

of society and to withdraw their attention from

the sober pursuits of honest industry. It is not

by encouraging this spirit that we shall best

pre- serve public virtue and promote the true

interests of our country. But if your currency

continues as exclusively paper as it now is, it

will foster this eager desire to amass wealth

without labor; it will multiply the number of

dependents on bank accommodations and bank

favors; the temptation to obtain money at any

sacrifice will become stronger and stronger, and

inevitably lead to corruption which will find

its way into your public councils and destroy,

at no distant day, the purity of your

Government. Some of the evils which arise from

this system of paper press with peculiar

hardship upon the class of society least able to

bear it. A portion of this currency frequently

becomes depreciated or worthless, and all of it

is easily counterfeited in such I a manner as to

require peculiar skill and much experience to

distinguish the counterfeit from the genuine

note. These frauds are most generally

perpetrated in the smaller notes, which are used

in the daily transactions of ordinary business;

and the losses occasioned by them are commonly

thrown upon the laboring classes of society

whose I situation and pursuits put it out of

their power to guard themselves from these

impositions and whose daily wages are necessary

for their subsistence. It is the duty of every

Government so to regulate its currency as to

protect this numerous class as far as

practicable from the impositions of avarice and

fraud. It is more especially the duty of the

United States where the Government is

emphatically the Government of the people, and

where this respectable portion of our citizens

are so proudly distinguished from the laboring

classes of all other nations by their

independent spirit, their love of liberty, their

intelligence, and their high tone of moral

character. Their industry in peace is the source

of our wealth; and their bravery in war has

covered us with glory; and the Government of the

United States will but ill discharge its duties

if it leaves them a prey to such dishonest

impositions. Yet it is evident that their

interests cannot be effectually protected unless

silver and gold are restored to circulation.

These views alone of the paper currency are

sufficient to care for immediate reform; but

there is another consideration which should

still more strongly press it upon your

attention.

Recent events have proved that the paper money

system of this country may be used as an engine

to undermine your free institutions; and that

those who desire to engross all power in the

hands of the few and to govern by corruption or

force are aware of its power and prepared to

employ it. Your banks now furnish your only

circulating medium, and money is plenty or

scarce according to the quantity of notes issued

by them. While they have capitals not greatly

disproportioned to each other, they are

competitors in business, and no one of them can

exercise dominion over the rest; and although,

in the present state of the currency, these

banks may and do operate injuriously upon the

habits of business, the pecuniary concerns, and

the moral tone of society; yet, from their

number and dispersed situation, they cannot

combine for the purpose of political influence;

and what- ever may be the dispositions of some

of them, their power of mischief must

necessarily be confined to a narrow space and

felt only in their immediate neighborhoods.

But when the charter for the Bank of the United

States was obtained from Congress, it perfected

the schemes of the paper system and gave to its

advocates the position they have struggled to

obtain from the commencement of the Federal

Government down to the present hour. The immense

capital and peculiar privileges bestowed upon it

enabled it to exercise despotic sway over the

other banks in every part of the country. From

its superior strength it could seriously injure,

if not destroy, the business of any one of them

which might incur its resentment; and it openly

claimed for itself the power of regulating the

currency throughout the United States. In other

words, it asserted (and it undoubtedly

possessed) the power to make money plenty or

scarce, at its pleasure, at any time, and in any

quarter of the Union, by controlling the issues

of other banks and permitting an expansion or

compelling a general contraction of the

circulating medium according to its own will.

The other banking institutions were sensible of

its strength, and they soon generally became its

obedient instruments, ready, at all times, to

execute its mandates; and with the banks

necessarily went, also, that numerous class of

persons in our commercial cities who depend

altogether on bank credits for their solvency

and means of business; and who are, there fore,

obliged for their own safety to propitiate the

favor of the money power by distinguished zeal

and devotion in its service. The result of the

ill-advised legislation which established this

great monopoly was to concentrate the whole

moneyed power of the Union, with its boundless

means of corruption and its numerous dependents,

under the direction and command of one

acknowledged head; thus organizing this

particular interest as one body and securing to

it unity and concert of action throughout the

United States and enabling it to bring forward,

upon any occasion, its entire and undivided

strength to support or defeat any measure of the

Government. In the hands of this formidable

power, thus perfectly organized, was also placed

unlimited dominion over the amount of the

circulating medium, giving it the power to

regulate the value of property and the fruits of

labor in every quarter of the Union and to

bestow prosperity or bring ruin upon any city or

section of the country as might best comport

with its own interest or policy.

We are not left to conjecture how the moneyed

power, thus organized and with such a weapon in

its hands, would be likely to use it. The

distress and alarm which pervaded and agitated

the whole country when the Bank of the United

States waged war upon the people in order to

compel them to submit to its demands cannot yet

be for gotten. The ruthless and unsparing temper

with which whole cities and communities were

oppressed, individuals impoverished and ruined,

and a scene of cheerful prosperity suddenly

changed into one of gloom and despondency ought

to be indelibly impressed on the memory of the

people of the United States. If such was its

power in a time of peace, what would it not have

been in a season of war with an enemy at your

doors? No nation but the freemen of the United

States could have come out victorious from such

a contest; yet, if you had not conquered, the

Government would have passed from the hands of

the many to the hands of the few; and this

organized money power, from its secret conclave,

would have dictated the choice of your highest

officers and compelled you to make peace or war

as best suited their own wishes. The forms of

your government might, for a time, have

remained; but its living spirit would have

departed from it.

The distress and sufferings inflicted on the

people by the bank are some of the fruits of

that system of policy which is continually

striving to enlarge the authority of the Federal

Government beyond the limits fixed by the

Constitution. The powers enumerated in that

instrument do not confer on Congress the right

to establish such a corporation as the Bank of

the United States; and the evil consequences

which followed may warn us of the danger of

departing from the true rule of construction and

of permitting temporary circum stances or the

hope of better promoting the public welfare to

influence, in any degree, our decisions upon the

extent of the authority of the General

Government. Let us abide by the Constitution as

it is written or amend it in the constitutional

mode if it is found to be defective.

The severe lessons of experience will, I doubt

not, be sufficient to prevent Congress from

again chartering such a monopoly, even if the

Constitution did not present an insuperable

objection to it. But you must remember, my

fellow citizens, that eternal vigilance by the

people is the price of liberty; and that you

must pay the price if you wish to secure the

blessing. It behooves you, therefore, to be

watchful in your States as well as in the

Federal Government. The power which the moneyed

interest can exercise, when concentrated under a

single head, and with our present system of

currency, was sufficiently demonstrated in the

struggle made by the Bank of the United States.

Defeated in the General Government, the same

class of intriguers and politicians will now

resort to the States and endeavor to obtain

there the same organization which they failed to

perpetuate in the Union; and with specious and

deceitful plans of public advantages and State

interests and State pride they will endeavor to

establish, in the different States, one moneyed

institution with overgrown capital and exclusive

privileges sufficient to enable it to control

the operations of the other banks. Such an

institution will be pregnant with the same evils

produced by the Bank of the United States,

although its sphere of action is more confined;

and in the State in which it is chartered the

money power will be able to embody its whole

strength and to move together with undivided

force to accomplish any object it may wish to

attain. You have already had abundant evidence

of its power to inflict injury upon the

agricultural, mechanical, and laboring classes

of society; and over those whose engagements in

trade or speculation render them dependent on

bank facilities, the dominion of the State

monopoly will be absolute, and their obedience

unlimited. With such a bank and a paper

currency, the money power would, in a few years,

govern the State and control its measures; and

if a sufficient number of States can be induced

to create such establishments, the time will

soon come when it will again take the field

against the United States and succeed in

perfecting and perpetuating its organization by

a charter from Congress.

It is one of the serious evils of our present

system of banking that it enables one class of

society, and that by no means a numerous one, by

its control over the currency to act injuriously

upon the interests of all the others and to

exercise more than its just proportion of

influence in political affairs. The

agricultural, the mechanical, and the laboring

classes have little or no share in the direction

of the great moneyed corporations; and from

their habits and the nature of their pursuits,

they are incapable of forming extensive

combinations to act together with united force.

Such concert of action may sometimes be produced

in a single city or in a small district of

country by means of personal communications with

each other; but they have no regular or active

correspondence with those who are engaged in

similar pursuits in distant places; they have

but little patronage to give to the press and

exercise but a small share of influence over it;

they have no crowd of dependents above them who

hope to grow rich without labor by their

countenance and favor and who are, therefore,

always ready to exercise their wishes. The

planter, the farmer, the mechanic, and the

laborer all know that their success depends upon

their own industry and economy and that they

must not expect to become suddenly rich by the

fruits of their toil. Yet these classes of

society form the great body of the people of the

United States; they are the bone and sinew of

the country; men who love liberty and desire

nothing but equal rights and equal laws and who,

moreover, hold the great mass of our national

wealth, although it is distributed in moderate

amounts among the millions of freemen who

possess it. But, with overwhelming numbers and

wealth on their side, they are in constant

danger of losing their fair influence in the

Government and with difficulty maintain their

just rights against the incessant efforts daily

made to encroach upon them. The mischief springs

from the power which the moneyed interest

derives from a paper currency which they are

able to control; from the multitude of

corporations with exclusive privileges which

they have succeeded in obtaining in the

different States and which are employed

altogether for their benefit; and unless you

become more watchful in your States and check

this spirit of monopoly and thirst for exclusive

privileges, you will, in the end, find that the

most important powers of Government have been

given or bartered away, and the control over

your dearest interests has passed into the hands

of these corporations.

The paper money system and its natural

associates, monopoly and exclusive privileges,

have already struck their roots deep in the

soil; and it will require all your efforts to

check its further growth and to eradicate the

evil. The men who profit by the abuses and

desire to perpetuate them will continue to

besiege the halls of legislation in the General

Government as well as in the States and will

seek, by every artifice, to mislead and deceive

the public servants. It is to yourselves that

you must look for safety and the means of

guarding and perpetuating your free

institutions. In your hands is rightfully placed

the sovereignty of the country and to you every

one placed in authority is ultimately

responsible. It is always in your power to see

that the wishes of the people are carried into

faithful execution, and their will, when once

made known, must sooner or later be obeyed. And

while the people remain, as I trust they ever

will, uncorrupted and incorruptible and continue

watchful and jealous of their rights, the

Government is safe, and the cause of freedom

will continue to triumph over all its enemies.

But it will require steady and persevering

exertions on your part to rid yourselves of the

iniquities and mischiefs of the paper system and

to check the spirit of monopoly and other abuses

which have sprung up with it and of which it is

the main support. So many interests are united

to resist all reform on this subject that you

must not hope the conflict will be a short one

nor success easy. My humble efforts have not

been spared, during my administration of the

Government, to restore the constitutional

currency of gold and silver; and something, I

trust, has been done towards the accomplishment

of this most desirable object. But enough yet

remains to require all your energy and

perseverance. The power, however, is in your

hands, and the remedy must and will be applied,

if you determine upon it.

While I am thus

endeavoring to press upon your attention the

principles which I deem of vital importance in

the domestic concerns of the country, I ought

not to pass over, without notice, the important

considerations which should govern your policy

toward foreign powers. It is, unquestionably,

our true interest to cultivate the most friendly

understanding with every nation and to avoid, by

every honorable means, the calamities of war;

and we shall best attain this object by

frankness and sincerity in our foreign

intercourse, by the prompt and faithful

execution of treaties, and by justice and

impartiality in our conduct to all. But no

nation, however desirous of can hope to escape

occasional collisions with other powers; and

soundest dictates of policy require that we

should place a condition to assert our rights if

a resort to force should necessary. Our local

situation, our long line of seacoast, numerous

bays, with deep rivers opening into the

interior, as our extended and still increasing

commerce, point to the natural means of defense.

It will, in the end, be found to be the cheapest

and most effectual; and now is the time, in a

season of peace, and with an overflowing

revenue, that we can, year after year, add to

its strength without increasing the burdens of

the people. It is your true policy. For your

navy will not only protect your rich and

flourishing commerce in distant seas, but will

enable you to reach and annoy the enemy and will

give to defense its greatest efficiency by

meeting danger at a distance from home. It is

impossible by any line of fortifications to

guard every point from attack against a hostile

force advancing from the ocean and selecting its

object; but they are indispensable to protect

cities from bombardment, dock yards and naval

arsenals from destruction; to give shelter to

merchant vessels in time of war, and to single

ships or weaker squadrons when pressed by

superior force. Fortifications of this

description cannot be too soon completed and

armed and placed in a condition of the most

perfect preparation. The abundant means we now

possess cannot be applied in any manner more

useful to the country; and when this is done and

our naval force sufficiently strengthened and

our militia armed, we need not fear that any

nation will wantonly insult us or needlessly

provoke hostilities. We shall more certainly

preserve peace when it is well understood that

we are prepared for war.

In presenting to

you, my fellow citizens, these parting counsels,

I have brought before you the leading principles

upon which I endeavored to administer the

Government in the high office with which you

twice honored me. Knowing that the path of

freedom is continually beset by enemies who

often assume the disguise of friends, I have

devoted the last hours of my public life to warn

you of the danger. The progress of the United

States under our free and happy institutions has

surpassed the most sanguine hopes of the

founders of the Republic. Our growth has been

rapid beyond all former example, in numbers, in

wealth, in knowledge, and all the useful arts

which contribute to the comforts and convenience

of man; and from the earliest ages of history to

the present day, there never have been thirteen

millions of people associated together in one

political body who enjoyed so much freedom and

happiness as the people of these United States.

You have no longer any cause to fear danger from

abroad; your strength and power are well known

throughout the civilized world, as well as the

high and gallant bearing of your sons. It is

from within, among yourselves, from cupidity,

from corruption, from disappointed ambition, and

inordinate thirst for power, that factions will

be formed and liberty endangered. It is against

such designs, whatever disguise the actors may

assume, that you have especially to guard

yourselves. You have the highest of human trust

committed to your care. Providence has showered

on this favored land blessings without number

and has chosen you as the guardian of freedom to

preserve it for the benefit of the human race.

May He who holds in his hands the destinies of

nations make you worthy of the favors He has

bestowed and enable you, with pure hearts and

pure hands and sleepless vigilance, to guard and

defend to to the end of time the great charge he

has committed to your keeping.

My own race is nearly run; advanced age and

failing health warn me that before long I must

pass beyond the reach of human event and cease

to feel the vicissitudes of human affairs. I

thank God that my life has been spent in a land

of liberty and that He has given me a heart to

love my country with the affection of a son.

And, filled with gratitude for your constant and

unwavering kindness, I bid you a last and

affectionate farewell.

More History

|

|