|

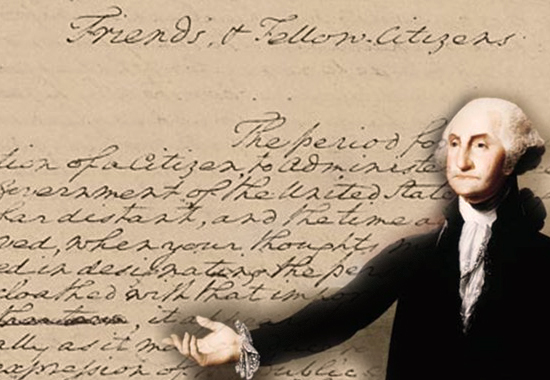

The First U.S. President Takes His Hat - Washington in 1796

Washington's Farewell Address

Go here for more about

George Washington.

George Washington.

Go here for more about

Washington's Farewell Address.

Washington's Farewell Address.

It follows the full text transcript of

George Washington's Farewell Address, published

on September 19, 1796, in the

American Daily Advertiser.

|

Friends and Fellow

Citizens: |

The period for a

new election of a citizen to administer the

executive government of the United States being

not far distant, and the time actually arrived

when your thoughts must be employed in

designating the person who is to be clothed with

that important trust, it appears to me proper,

especially as it may conduce to a more distinct

expression of the public voice, that I should

now apprise you of the resolution I have formed,

to decline being considered among the number of

those out of whom a choice is to be made.

I beg you, at the same time, to do me the

justice to be assured that this resolution has

not been taken without a strict regard to all

the considerations appertaining to the relation

which binds a dutiful citizen to his country;

and that in withdrawing the tender of service,

which silence in my situation might imply, I am

influenced by no diminution of zeal for your

future interest, no deficiency of grateful

respect for your past kindness, but am supported

by a full conviction that the step is compatible

with both.

The acceptance of, and continuance hitherto in,

the office to which your suffrages have twice

called me have been a uniform sacrifice of

inclination to the opinion of duty and to a

deference for what appeared to be your desire. I

constantly hoped that it would have been much

earlier in my power, consistently with motives

which I was not at liberty to disregard, to

return to that retirement from which I had been

reluctantly drawn. The strength of my

inclination to do this, previous to the last

election, had even led to the preparation of an

address to declare it to you; but mature

reflection on the then perplexed and critical

posture of our affairs with foreign nations, and

the unanimous advice of persons entitled to my

confidence, impelled me to abandon the idea.

I rejoice that the state of your concerns,

external as well as internal, no longer renders

the pursuit of inclination incompatible with the

sentiment of duty or propriety, and am

persuaded, whatever partiality may be retained

for my services, that, in the present

circumstances of our country, you will not

disapprove my determination to retire.

The impressions with which I first undertook the

arduous trust were explained on the proper

occasion. In the discharge of this trust, I will

only say that I have, with good intentions,

contributed towards the organization and

administration of the government the best

exertions of which a very fallible judgment was

capable. Not unconscious in the outset of the

inferiority of my qualifications, experience in

my own eyes, perhaps still more in the eyes of

others, has strengthened the motives to

diffidence of myself; and every day the

increasing weight of years admonishes me more

and more that the shade of retirement is as

necessary to me as it will be welcome. Satisfied

that if any circumstances have given peculiar

value to my services, they were temporary, I

have the consolation to believe that, while

choice and prudence invite me to quit the

political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.

In looking forward to the moment which is

intended to terminate the career of my public

life, my feelings do not permit me to suspend

the deep acknowledgment of that debt of

gratitude which I owe to my beloved country for

the many honors it has conferred upon me; still

more for the steadfast confidence with which it

has supported me; and for the opportunities I

have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable

attachment, by services faithful and

persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my

zeal. If benefits have resulted to our country

from these services, let it always be remembered

to your praise, and as an instructive example in

our annals, that under circumstances in which

the passions, agitated in every direction, were

liable to mislead, amidst appearances sometimes

dubious, vicissitudes of fortune often

discouraging, in situations in which not

unfrequently want of success has countenanced

the spirit of criticism, the constancy of your

support was the essential prop of the efforts,

and a guarantee of the plans by which they were

effected. Profoundly penetrated with this idea,

I shall carry it with me to my grave, as a

strong incitement to unceasing vows that heaven

may continue to you the choicest tokens of its

beneficence; that your union and brotherly

affection may be perpetual; that the free

Constitution, which is the work of your hands,

may be sacredly maintained; that its

administration in every department may be

stamped with wisdom and virtue; that, in fine,

the happiness of the people of these States,

under the auspices of liberty, may be made

complete by so careful a preservation and so

prudent a use of this blessing as will acquire

to them the glory of recommending it to the

applause, the affection, and adoption of every

nation which is yet a stranger to it.

Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But a solicitude

for your welfare, which cannot end but with my

life, and the apprehension of danger, natural to

that solicitude, urge me, on an occasion like

the present, to offer to your solemn

contemplation, and to recommend to your frequent

review, some sentiments which are the result of

much reflection, of no inconsiderable

observation, and which appear to me

all-important to the permanency of your felicity

as a people. These will be offered to you with

the more freedom, as you can only see in them

the disinterested warnings of a parting friend,

who can possibly have no personal motive to bias

his counsel. Nor can I forget, as an

encouragement to it, your indulgent reception of

my sentiments on a former and not dissimilar

occasion.

Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every

ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of

mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the

attachment.

The unity of government which constitutes you

one people is also now dear to you. It is justly

so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of

your real independence, the support of your

tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your

safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty

which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to

foresee that, from different causes and from

different quarters, much pains will be taken,

many artifices employed to weaken in your minds

the conviction of this truth; as this is the

point in your political fortress against which

the batteries of internal and external enemies

will be most constantly and actively (though

often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is

of infinite moment that you should properly

estimate the immense value of your national

union to your collective and individual

happiness; that you should cherish a cordial,

habitual, and immovable attachment to it;

accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it

as of the palladium of your political safety and

prosperity; watching for its preservation with

jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may

suggest even a suspicion that it can in any

event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning

upon the first dawning of every attempt to

alienate any portion of our country from the

rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now

link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy

and interest. Citizens, by birth or choice, of a

common country, that country has a right to

concentrate your affections. The name of

American, which belongs to you in your national

capacity, must always exalt the just pride of

patriotism more than any appellation derived

from local discriminations. With slight shades

of difference, you have the same religion,

manners, habits, and political principles. You

have in a common cause fought and triumphed

together; the independence and liberty you

possess are the work of joint counsels, and

joint efforts of common dangers, sufferings, and

successes.

But these considerations, however powerfully

they address themselves to your sensibility, are

greatly outweighed by those which apply more

immediately to your interest. Here every portion

of our country finds the most commanding motives

for carefully guarding and preserving the union

of the whole.

The North, in an unrestrained intercourse with

the South, protected by the equal laws of a

common government, finds in the productions of

the latter great additional resources of

maritime and commercial enterprise and precious

materials of manufacturing industry. The South,

in the same intercourse, benefiting by the

agency of the North, sees its agriculture grow

and its commerce expand. Turning partly into its

own channels the seamen of the North, it finds

its particular navigation invigorated; and,

while it contributes, in different ways, to

nourish and increase the general mass of the

national navigation, it looks forward to the

protection of a maritime strength, to which

itself is unequally adapted. The East, in a like

intercourse with the West, already finds, and in

the progressive improvement of interior

communications by land and water, will more and

more find a valuable vent for the commodities

which it brings from abroad, or manufactures at

home. The West derives from the East supplies

requisite to its growth and comfort, and, what

is perhaps of still greater consequence, it must

of necessity owe the secure enjoyment of

indispensable outlets for its own productions to

the weight, influence, and the future maritime

strength of the Atlantic side of the Union,

directed by an indissoluble community of

interest as one nation. Any other tenure by

which the West can hold this essential

advantage, whether derived from its own separate

strength, or from an apostate and unnatural

connection with any foreign power, must be

intrinsically precarious.

While, then, every part of our country thus

feels an immediate and particular interest in

union, all the parts combined cannot fail to

find in the united mass of means and efforts

greater strength, greater resource,

proportionably greater security from external

danger, a less frequent interruption of their

peace by foreign nations; and, what is of

inestimable value, they must derive from union

an exemption from those broils and wars between

themselves, which so frequently afflict

neighboring countries not tied together by the

same governments, which their own rival ships

alone would be sufficient to produce, but which

opposite foreign alliances, attachments, and

intrigues would stimulate and embitter. Hence,

likewise, they will avoid the necessity of those

overgrown military establishments which, under

any form of government, are inauspicious to

liberty, and which are to be regarded as

particularly hostile to republican liberty. In

this sense it is that your union ought to be

considered as a main prop of your liberty, and

that the love of the one ought to endear to you

the preservation of the other.

These considerations speak a persuasive language

to every reflecting and virtuous mind, and

exhibit the continuance of the Union as a

primary object of patriotic desire. Is there a

doubt whether a common government can embrace so

large a sphere? Let experience solve it. To

listen to mere speculation in such a case were

criminal. We are authorized to hope that a

proper organization of the whole with the

auxiliary agency of governments for the

respective subdivisions, will afford a happy

issue to the experiment. It is well worth a fair

and full experiment. With such powerful and

obvious motives to union, affecting all parts of

our country, while experience shall not have

demonstrated its impracticability, there will

always be reason to distrust the patriotism of

those who in any quarter may endeavor to weaken

its bands.

In contemplating the causes which may disturb

our Union, it occurs as matter of serious

concern that any ground should have been

furnished for characterizing parties by

geographical discriminations, Northern and

Southern, Atlantic and Western; whence designing

men may endeavor to excite a belief that there

is a real difference of local interests and

views. One of the expedients of party to acquire

influence within particular districts is to

misrepresent the opinions and aims of other

districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much

against the jealousies and heartburnings which

spring from these misrepresentations; they tend

to render alien to each other those who ought to

be bound together by fraternal affection. The

inhabitants of our Western country have lately

had a useful lesson on this head; they have

seen, in the negotiation by the Executive, and

in the unanimous ratification by the Senate, of

the treaty with Spain, and in the universal

satisfaction at that event, throughout the

United States, a decisive proof how unfounded

were the suspicions propagated among them of a

policy in the General Government and in the

Atlantic States unfriendly to their interests in

regard to the Mississippi; they have been

witnesses to the formation of two treaties, that

with Great Britain, and that with Spain, which

secure to them everything they could desire, in

respect to our foreign relations, towards

confirming their prosperity. Will it not be

their wisdom to rely for the preservation of

these advantages on the Union by which they were

procured ? Will they not henceforth be deaf to

those advisers, if such there are, who would

sever them from their brethren and connect them

with aliens?

To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a

government for the whole is indispensable. No

alliance, however strict, between the parts can

be an adequate substitute; they must inevitably

experience the infractions and interruptions

which all alliances in all times have

experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth,

you have improved upon your first essay, by the

adoption of a constitution of government better

calculated than your former for an intimate

union, and for the efficacious management of

your common concerns. This government, the

offspring of our own choice, uninfluenced and

unawed, adopted upon full investigation and

mature deliberation, completely free in its

principles, in the distribution of its powers,

uniting security with energy, and containing

within itself a provision for its own amendment,

has a just claim to your confidence and your

support. Respect for its authority, compliance

with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are

duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of

true liberty. The basis of our political systems

is the right of the people to make and to alter

their constitutions of government. But the

Constitution which at any time exists, till

changed by an explicit and authentic act of the

whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all.

The very idea of the power and the right of the

people to establish government presupposes the

duty of every individual to obey the established

government.

All obstructions to the execution of the laws,

all combinations and associations, under

whatever plausible character, with the real

design to direct, control, counteract, or awe

the regular deliberation and action of the

constituted authorities, are destructive of this

fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency.

They serve to organize faction, to give it an

artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in

the place of the delegated will of the nation

the will of a party, often a small but artful

and enterprising minority of the community; and,

according to the alternate triumphs of different

parties, to make the public administration the

mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous

projects of faction, rather than the organ of

consistent and wholesome plans digested by

common counsels and modified by mutual

interests.

However combinations or associations of the

above description may now and then answer

popular ends, they are likely, in the course of

time and things, to become potent engines, by

which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men

will be enabled to subvert the power of the

people and to usurp for themselves the reins of

government, destroying afterwards the very

engines which have lifted them to unjust

dominion.

Towards the preservation of your government, and

the permanency of your present happy state, it

is requisite, not only that you steadily

discountenance irregular oppositions to its

acknowledged authority, but also that you resist

with care the spirit of innovation upon its

principles, however specious the pretexts. One

method of assault may be to effect, in the forms

of the Constitution, alterations which will

impair the energy of the system, and thus to

undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In

all the changes to which you may be invited,

remember that time and habit are at least as

necessary to fix the true character of

governments as of other human institutions; that

experience is the surest standard by which to

test the real tendency of the existing

constitution of a country; that facility in

changes, upon the credit of mere hypothesis and

opinion, exposes to perpetual change, from the

endless variety of hypothesis and opinion; and

remember, especially, that for the efficient

management of your common interests, in a

country so extensive as ours, a government of as

much vigor as is consistent with the perfect

security of liberty is indispensable. Liberty

itself will find in such a government, with

powers properly distributed and adjusted, its

surest guardian. It is, indeed, little else than

a name, where the government is too feeble to

withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine

each member of the society within the limits

prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in

the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights

of person and property.

I have already intimated to you the danger of

parties in the State, with particular reference

to the founding of them on geographical

discriminations. Let me now take a more

comprehensive view, and warn you in the most

solemn manner against the baneful effects of the

spirit of party generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from

our nature, having its root in the strongest

passions of the human mind. It exists under

different shapes in all governments, more or

less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in

those of the popular form, it is seen in its

greatest rankness, and is truly their worst

enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over

another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge,

natural to party dissension, which in different

ages and countries has perpetrated the most

horrid enormities, is itself a frightful

despotism. But this leads at length to a more

formal and permanent despotism. The disorders

and miseries which result gradually incline the

minds of men to seek security and repose in the

absolute power of an individual; and sooner or

later the chief of some prevailing faction, more

able or more fortunate than his competitors,

turns this disposition to the purposes of his

own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this

kind (which nevertheless ought not to be

entirely out of sight), the common and continual

mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient

to make it the interest and duty of a wise

people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils

and enfeeble the public administration. It

agitates the community with ill-founded

jealousies and false alarms, kindles the

animosity of one part against another, foments

occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the

door to foreign influence and corruption, which

finds a facilitated access to the government

itself through the channels of party passions.

Thus the policy and the will of one country are

subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free

countries are useful checks upon the

administration of the government and serve to

keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within

certain limits is probably true; and in

governments of a monarchical cast, patriotism

may look with indulgence, if not with favor,

upon the spirit of party. But in those of the

popular character, in governments purely

elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged.

From their natural tendency, it is certain there

will always be enough of that spirit for every

salutary purpose. And there being constant

danger of excess, the effort ought to be by

force of public opinion, to mitigate and assuage

it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a

uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a

flame, lest, instead of warming, it should

consume.

It is important, likewise, that the habits of

thinking in a free country should inspire

caution in those entrusted with its

administration, to confine themselves within

their respective constitutional spheres,

avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one

department to encroach upon another. The spirit

of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers

of all the departments in one, and thus to

create, whatever the form of government, a real

despotism. A just estimate of that love of

power, and proneness to abuse it, which

predominates in the human heart, is sufficient

to satisfy us of the truth of this position. The

necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise

of political power, by dividing and distributing

it into different depositaries, and constituting

each the guardian of the public weal against

invasions by the others, has been evinced by

experiments ancient and modern; some of them in

our country and under our own eyes. To preserve

them must be as necessary as to institute them.

If, in the opinion of the people, the

distribution or modification of the

constitutional powers be in any particular

wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in

the way which the Constitution designates. But

let there be no change by usurpation; for though

this, in one instance, may be the instrument of

good, it is the customary weapon by which free

governments are destroyed. The precedent must

always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any

partial or transient benefit, which the use can

at any time yield.

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to

political prosperity, religion and morality are

indispensable supports. In vain would that man

claim the tribute of patriotism, who should

labor to subvert these great pillars of human

happiness, these firmest props of the duties of

men and citizens. The mere politician, equally

with the pious man, ought to respect and to

cherish them. A volume could not trace all their

connections with private and public felicity.

Let it simply be asked: Where is the security

for property, for reputation, for life, if the

sense of religious obligation desert the oaths

which are the instruments of investigation in

courts of justice ? And let us with caution

indulge the supposition that morality can be

maintained without religion. Whatever may be

conceded to the influence of refined education

on minds of peculiar structure, reason and

experience both forbid us to expect that

national morality can prevail in exclusion of

religious principle.

It is substantially true that virtue or morality

is a necessary spring of popular government. The

rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to

every species of free government. Who that is a

sincere friend to it can look with indifference

upon attempts to shake the foundation of the

fabric?

Promote then, as an object of primary

importance, institutions for the general

diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the

structure of a government gives force to public

opinion, it is essential that public opinion

should be enlightened.

As a very important source of strength and

security, cherish public credit. One method of

preserving it is to use it as sparingly as

possible, avoiding occasions of expense by

cultivating peace, but remembering also that

timely disbursements to prepare for danger

frequently prevent much greater disbursements to

repel it, avoiding likewise the accumulation of

debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense,

but by vigorous exertion in time of peace to

discharge the debts which unavoidable wars may

have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon

posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to

bear. The execution of these maxims belongs to

your representatives, but it is necessary that

public opinion should co-operate. To facilitate

to them the performance of their duty, it is

essential that you should practically bear in

mind that towards the payment of debts there

must be revenue; that to have revenue there must

be taxes; that no taxes can be devised which are

not more or less inconvenient and unpleasant;

that the intrinsic embarrassment, inseparable

from the selection of the proper objects (which

is always a choice of difficulties), ought to be

a decisive motive for a candid construction of

the conduct of the government in making it, and

for a spirit of acquiescence in the measures for

obtaining revenue, which the public exigencies

may at any time dictate.

Observe good faith and justice towards all

nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all.

Religion and morality enjoin this conduct; and

can it be, that good policy does not equally

enjoin it? It will be worthy of a free,

enlightened, and at no distant period, a great

nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and

too novel example of a people always guided by

an exalted justice and benevolence. Who can

doubt that, in the course of time and things,

the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any

temporary advantages which might be lost by a

steady adherence to it ? Can it be that

Providence has not connected the permanent

felicity of a nation with its virtue ? The

experiment, at least, is recommended by every

sentiment which ennobles human nature. Alas! is

it rendered impossible by its vices?

In the execution of such a plan, nothing is more

essential than that permanent, inveterate

antipathies against particular nations, and

passionate attachments for others, should be

excluded; and that, in place of them, just and

amicable feelings towards all should be

cultivated. The nation which indulges towards

another a habitual hatred or a habitual fondness

is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its

animosity or to its affection, either of which

is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty

and its interest. Antipathy in one nation

against another disposes each more readily to

offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight

causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and

intractable, when accidental or trifling

occasions of dispute occur. Hence, frequent

collisions, obstinate, envenomed, and bloody

contests. The nation, prompted by ill-will and

resentment, sometimes impels to war the

government, contrary to the best calculations of

policy. The government sometimes participates in

the national propensity, and adopts through

passion what reason would reject; at other times

it makes the animosity of the nation subservient

to projects of hostility instigated by pride,

ambition, and other sinister and pernicious

motives. The peace often, sometimes perhaps the

liberty, of nations, has been the victim.

So likewise, a passionate attachment of one

nation for another produces a variety of evils.

Sympathy for the favorite nation, facilitating

the illusion of an imaginary common interest in

cases where no real common interest exists, and

infusing into one the enmities of the other,

betrays the former into a participation in the

quarrels and wars of the latter without adequate

inducement or justification. It leads also to

concessions to the favorite nation of privileges

denied to others which is apt doubly to injure

the nation making the concessions; by

unnecessarily parting with what ought to have

been retained, and by exciting jealousy,

ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the

parties from whom equal privileges are withheld.

And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded

citizens (who devote themselves to the favorite

nation), facility to betray or sacrifice the

interests of their own country, without odium,

sometimes even with popularity; gilding, with

the appearances of a virtuous sense of

obligation, a commendable deference for public

opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the

base or foolish compliances of ambition,

corruption, or infatuation.

As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable

ways, such attachments are particularly alarming

to the truly enlightened and independent

patriot. How many opportunities do they afford

to tamper with domestic factions, to practice

the arts of seduction, to mislead public

opinion, to influence or awe the public

councils? Such an attachment of a small or weak

towards a great and powerful nation dooms the

former to be the satellite of the latter.

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence

(I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens)

the jealousy of a free people ought to be

constantly awake, since history and experience

prove that foreign influence is one of the most

baneful foes of republican government. But that

jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it

becomes the instrument of the very influence to

be avoided, instead of a defense against it.

Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and

excessive dislike of another cause those whom

they actuate to see danger only on one side, and

serve to veil and even second the arts of

influence on the other. Real patriots who may

resist the intrigues of the favorite are liable

to become suspected and odious, while its tools

and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of

the people, to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us in regard to

foreign nations is in extending our commercial

relations, to have with them as little political

connection as possible. So far as we have

already formed engagements, let them be

fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us

stop. Europe has a set of primary interests

which to us have none; or a very remote

relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent

controversies, the causes of which are

essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence,

therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate

ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary

vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary

combinations and collisions of her friendships

or enmities.

Our detached and distant situation invites and

enables us to pursue a different course. If we

remain one people under an efficient government.

the period is not far off when we may defy

material injury from external annoyance; when we

may take such an attitude as will cause the

neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be

scrupulously respected; when belligerent

nations, under the impossibility of making

acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard

the giving us provocation; when we may choose

peace or war, as our interest, guided by

justice, shall counsel.

Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a

situation? Why quit our own to stand upon

foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny

with that of any part of Europe, entangle our

peace and prosperity in the toils of European

ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice?

It is our true policy to steer clear of

permanent alliances with any portion of the

foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at

liberty to do it; for let me not be understood

as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing

engagements. I hold the maxim no less applicable

to public than to private affairs, that honesty

is always the best policy. I repeat it,

therefore, let those engagements be observed in

their genuine sense. But, in my opinion, it is

unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves by suitable

establishments on a respectable defensive

posture, we may safely trust to temporary

alliances for extraordinary emergencies.

Harmony, liberal intercourse with all nations,

are recommended by policy, humanity, and

interest. But even our commercial policy should

hold an equal and impartial hand; neither

seeking nor granting exclusive favors or

preferences; consulting the natural course of

things; diffusing and diversifying by gentle

means the streams of commerce, but forcing

nothing; establishing (with powers so disposed,

in order to give trade a stable course, to

define the rights of our merchants, and to

enable the government to support them)

conventional rules of intercourse, the best that

present circumstances and mutual opinion will

permit, but temporary, and liable to be from

time to time abandoned or varied, as experience

and circumstances shall dictate; constantly

keeping in view that it is folly in one nation

to look for disinterested favors from another;

that it must pay with a portion of its

independence for whatever it may accept under

that character; that, by such acceptance, it may

place itself in the condition of having given

equivalents for nominal favors, and yet of being

reproached with ingratitude for not giving more.

There can be no greater error than to expect or

calculate upon real favors from nation to

nation. It is an illusion, which experience must

cure, which a just pride ought to discard.

In offering to you, my countrymen, these

counsels of an old and affectionate friend, I

dare not hope they will make the strong and

lasting impression I could wish; that they will

control the usual current of the passions, or

prevent our nation from running the course which

has hitherto marked the destiny of nations. But,

if I may even flatter myself that they may be

productive of some partial benefit, some

occasional good; that they may now and then

recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to

warn against the mischiefs of foreign intrigue,

to guard against the impostures of pretended

patriotism; this hope will be a full recompense

for the solicitude for your welfare, by which

they have been dictated.

How far in the discharge of my official duties I

have been guided by the principles which have

been delineated, the public records and other

evidences of my conduct must witness to you and

to the world. To myself, the assurance of my own

conscience is, that I have at least believed

myself to be guided by them.

In relation to the still subsisting war in

Europe, my proclamation of the twenty-second of

April, I793, is the index of my plan. Sanctioned

by your approving voice, and by that of your

representatives in both houses of Congress, the

spirit of that measure has continually governed

me, uninfluenced by any attempts to deter or

divert me from it.

After deliberate examination, with the aid of

the best lights I could obtain, I was well

satisfied that our country, under all the

circumstances of the case, had a right to take,

and was bound in duty and interest to take, a

neutral position. Having taken it, I determined,

as far as should depend upon me, to maintain it,

with moderation, perseverance, and firmness.

The considerations which respect the right to

hold this conduct, it is not necessary on this

occasion to detail. I will only observe that,

according to my understanding of the matter,

that right, so far from being denied by any of

the belligerent powers, has been virtually

admitted by all.

The duty of holding a neutral conduct may be

inferred, without anything more, from the

obligation which justice and humanity impose on

every nation, in cases in which it is free to

act, to maintain inviolate the relations of

peace and amity towards other nations.

The inducements of interest for observing that

conduct will best be referred to your own

reflections and experience. With me a

predominant motive has been to endeavor to gain

time to our country to settle and mature its yet

recent institutions, and to progress without

interruption to that degree of strength and

consistency which is necessary to give it,

humanly speaking, the command of its own

fortunes.

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my

administration, I am unconscious of intentional

error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my

defects not to think it probable that I may have

committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I

fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or

mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I

shall also carry with me the hope that my

country will never cease to view them with

indulgence; and that, after forty five years of

my life dedicated to its service with an upright

zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will

be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be

to the mansions of rest.

Relying on its kindness in this as in other

things, and actuated by that fervent love

towards it, which is so natural to a man who

views in it the native soil of himself and his

progenitors for several generations, I

anticipate with pleasing expectation that

retreat in which I promise myself to realize,

without alloy, the sweet enjoyment of partaking,

in the midst of my fellow-citizens, the benign

influence of good laws under a free government,

the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the

happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares,

labors, and dangers.

More History

|

|