|

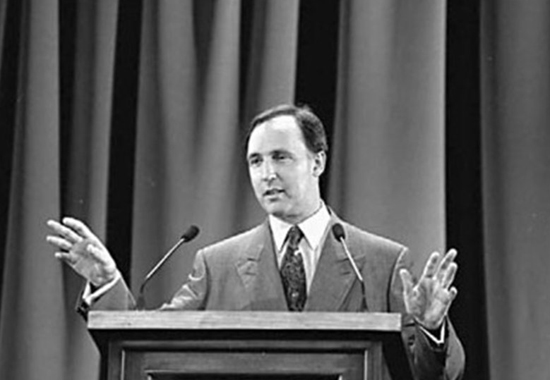

GUIDING POLICIES WITH A KIND AND

THOUGHTFUL HAND - PAUL KEATING

Financial Innovation

It follows the full text transcript of

Paul Keating's Financial Innovation speech,

delivered at the Second Asian Leadership Conference, Seoul,

Korea - February 21, 2008.

|

Your host, Chosun

Ilbo, |

has asked me to

concentrate my luncheon address on the subject

of financial and labor market reform. Your host

has asked me to draw upon my experience in

introducing reforms to those markets in

Australia during the period when I was Treasurer

and Prime Minister.

With a new President and new Government coming

to office in Korea, President-elect Lee Myung

Back has, amongst other things, foreshadowed

financial market reforms to raise Korea's global

competitiveness.

In setting this subject for lunch, Chosun Ilbo

has asked me to reflect upon similar changes

made in Australia 25 years ago and more

recently, 15 years ago to give today's luncheon

guests some clue from a practitioner as to the

importance of these reforms and how they might

work in a Korean context.

Perhaps I should make the overarching and key

point first and make it succinctly. It is this:

any country has a right and can choose the

economic pathway of economic nationalism and

protectionism. But supporters of that policy

have to know that such a pathway, while having

some popular appeal, carries with it the choice

of sub-optimal or lower rates of economic growth

coupled with lower and slower rates of income

growth.

Perhaps I could paraphrase it this way: open

markets provide more opportunities, more growth

and faster income growth. But they require

greater challenges from the ensuing adjustments

and the greater requirement on the political

system to respond to the need for those

adjustments.

Open markets also do something else: by allowing

competitive pricing, they make clear which parts

of the economy are true profit centers and

which, by contrast, are the parts which perform

sub-optimally.

These outcomes inform investment choices such

that capital is drawn to those parts of the

economy where enhanced profitability lifts

returns and with these returns, GDP growth. In

other words, open markets identify the more

likely and natural parts of the economy where

scarce capital is best employed.

What impediments to trade, such as tariffs and

quotas, financial regulation and labor market

rigidities do, is to falsely pump up particular

sectors and industries within the economy,

making them appear more attractive and

profitable than they really are. Whereas, those

nominal attractions can only exist at the

expense of the broader community by way of

diminished incomes and lower GDP growth.

Like I say, we all have a choice but why, if we

have the option and the power would we take the

low income road over the high income one, simply

to satisfy entrenched interest groups and to

keep the political system free from trouble?

There is no revelation about this but the fact

that these truths are so often ignored makes

their recital worthwhile.

Politicians and political parties exist for one

purpose and one purpose only: to safeguard the

people while making the required and continuing

changes to the fabric of their economies and

their societies.

Politicians who are in the business of politics

but not in the business of change let their

communities down badly. The political game is

about, and only about, getting the changes

through. Bureaucracies are more than capable of

running an existing system, but bureaucrats are

not capable of changing it.

The great curse of modern day political life is

incrementalism. Moving change along, millimeter

by millimeter, taking few political risks while

pretending to be the elector's friend.

Mandates for paradigm shifts in an economy or

society belong only to politicians and to the

political system; they can never belong to

bureaucracies. Bureaucracies have no political

power on which to draw; what they do, sometimes

well and sometimes clumsily, is to filch morsels

of power which they use to incrementally move

along their own agendas.

It is no accident, that in countries where

bureaucracies have been in the ascendancy, we

find generally slower rates of economic growth

and slower rates of income growth.

Decisive cabinet government aided and abetted by

a competent bureaucracy is the highway to

change.

With that in mind and with a new government

about to take office in South Korea, your hosts

have asked me to say something about the

financial system and financial market reform.

When I first began opening the financial markets

in Australia in 1983 I used to talk about a

sclerosis which inhabited the Australian

financial system. And I used to apply the

analogy of saying we needed to clear the

financial arteries to get blood to the muscle of

the economy . That remark is as true today of

unreformed financial systems as it was then.

Open and porous financial markets can bring

financial resources to parts of the economy that

were undreamt of even 30 years ago. Financial

deregulation allows financial engineering and

packaging of a kind which the old regulated and

traditional financial system was unable to

provide. And, more importantly, unwilling to

try.

Most financial systems built around deposit

taking institutions were characterized as high

margin businesses, offering a relatively limited

range of services. Institutions of this kind

serve a society particularly badly by making

people pay too high a margin for financial

resources while limiting the size of the group

who qualify to enjoy those resources. Low

margin, big volume, fungible financial services

are able to help the great body of the community

into assets and services they require. In doing

so, they promote higher GDP growth.

The absence of unnecessary financial regulation,

also underwrites the more rapid development of

capital markets; those places where financial

resources are available to industry and commerce

other than through the intermediation of

traditional banks. For instance, Japan is the

model of a tops down bank intermediated

financial economy where, on the other hand the

United States has been the model of a much more

horizontal financial structure where

corporations and individuals have access to

capital through a vibrant capital market. Where

banks do what banks should do: look after the

consumer, the householder and the small business

entrepreneur.

Let's say of its essence; financial regulation

represents a set of structures most valuable to

the already wealthy while deregulation, openness

and fungibility present avenues which are most

valuable to the clever and the imaginative. When

a society leaves the door shut to the clever and

the imaginative while leaving it remain open to

those of established wealth, that society is

heading for second best outcomes.

That said, financial innovation also carries

with it ongoing adjustment problems and

distortions as we have seen in the United States

more latterly.

A sustained period of economic expansion like

the one we have experienced since 1982 will

generate an ever growing role for the financial

economy in world economic affairs. A 25 year

expansion characterized by low inflation and

with less circumscribed financial markets will

inevitably underwrite an expanding role for

financial services in our economic life. Indeed,

we have seen a proliferation of institutions and

services of a kind never before witnessed. And

this period, at least for half of it, has also

been characterized by accommodating monetary

conditions and high levels of liquidity induced,

in the main, by central banks.

The outcome has been a pot au feu ; a financial

milieu without precedence in financial history.

Financial innovation in this period has lead to

all sorts of financial engineering and packaging

to get financial resources into every crack and

crevice of the economy, while on the asset side,

ownership of those resources has been spread to

the four corners of the earth under every

instrument imaginable. Each new instrument

brings another new name: collateralized debt

obligations, or CDOs, derivatives, hedges,

swaps, securitized bonds and all manner of

financial units, be they in listed trusts or

private portfolios.

The fact is, for the first time in modern

history we now have a financial system whose

affairs and influences, are beyond the reach and

remedy of central banks.

However true this is, would we have turned our

back on the financial innovation which has

lubricated the last 25 year expansion; or would

we have opted for the safe house of bank

intermediated economies run in clubby cabals by

central banks, commercial banks and finance

ministries?

The answer has to be, that of course, we should

have preferred innovation over regulation,

notwithstanding the problems that too often

accompany innovation. The current sub-prime

crisis in the United States teaches us again,

that no amount of financial slicing and dicing

can turn a bad credit into a good credit.

If sub-prime loans were bad to begin with they

remained bad even as they were sliced and diced

into a collateralized security held by

unsuspecting investors. And let me add, that

none of these tendencies have been helped by

central banks who feel it is their bounden duty

to underwrite the financial adventurism of

investment banks and PE funds, by putting onto

the state the contingent cost of financial

miscalculation.

I do not think it is too much to claim that as a

consequence of the behavior of central banks and

their opportunistic clients, that moral hazard

has become the leitmotif of financial services.

This has to be a worry for all governments and

all prudential supervisors. But it is a worry

that we have to work our way through, so that we

can enjoy the advantageous aspects of financial

innovation while seeking to limit the fallout to

investors and the state alike.

North Asia, especially China and South Korea

have an enormous stake in getting the design of

their financial systems right. With economies

growing in the order of 8 to 11 percent in a

year, the ongoing resourcing of these economies

will not be possible unless their financial

systems move in tandem or are allowed to move in

tandem, with economic expansion.

And what is true of financial markets is just as

true as of labor markets.

Policy toward labor markets should be such as to

encourage labor to go to the most productive

places in the economy; to secure the greatest

increments to income. Productivity based wage

adjustments therefore represent the best way of

lifting incomes while holding down inflation.

And this is best accomplished by labor market

mobility with workers being free to switch their

time to the best jobs.

Social democratic states, very properly have

another objective: and that is to guarantee that

working people are able to enjoy a living wage,

one that lifts them and their families above the

poverty line. This can take the form of a

legislated minimum or a basic award but in

whatever form, it provides the foundation of a

civil society. We should always remember that

the point of economic policy is economic wealth

and social progress. It should never be about

top end wealth provided off the back of an army

of working poor, denied the kind of wages and

conditions that are conducive to the sustenance

of families.

We ought remember that in that great cauldron of

opportunity, the United States, real wages have

not risen since the early 1980s. That is, the

huge increments to productivity from the late

1990s on, have gone solely to profits and to

those lucky individuals at the uppermost reaches

of the corporate and financial system. This

represents a massive indictment of the United

States as the country of the fair society. This

is not a model which will suit rising societies

particularly of the Asian variety, which rely

upon the family unit, family cohesion and family

income as their nation's basic building block.

What a country needs is wage justice with full

employment. Had by directing national financial

resources to the appropriate and best parts of

the economy, unfettered by the distortions of

protectionism. Investment of the kind which,

through productivity, is able to lift wages and

profits simultaneously. Any fool can run a low

wage economy in the quest for low prices and

competitiveness, what we need are clever people

to run systems which are productivity inducing;

where real wages rise with GDP and where

competitiveness is not had unfairly from the

sweat of the low paid.

There will always be groups in the labor market

whose positions are so weak that they are unable

to bargain their way into high wages, to garner

a share of the productivity. This is invariably

true for women and young people and the broadly

unskilled. Policy has to work at protecting

these vulnerable people from exploitation while

the better off are able to reasonably enjoy

their economic rewards.

There is a real challenge here: we want flexible

and mobile labor markets with earnings related

to productivity but decency demands that we

should have this only in the context of safety

nets for the disadvantaged.

Education of course, provides the great spring

board of opportunity including, into higher

incomes. This is why an economy becoming more

urbanized, with greater service orientation has

to have a premium on education. Education is the

conduit through which higher levels of

productivity are had.

Education has been a notable and strong trend in

Korea; it knows the way forward in the post

industrial age. A country like Korea must

continue to lift itself up the international

division of labor and not be left behind to

compete with low wage countries.

There is nothing more noble than lifting the

great body of a population into higher levels of

employment and income; indeed, there can be

nothing more uplifting for a political system

than lifting up the great body of a community.

But this can only be done by governments

competent in the ways of the world: knowing

about the economy, knowing about business,

knowing about the financial system, knowing

about the workforce. Guiding policies with a

kind and thoughtful hand.

Financial, product and labor market deregulation

has brought much wealth to countries which have

promoted these policies. Australia, as a case in

point, has now experienced a continuous 17 year

expansion averaging near 4% GDP growth per annum

with inflation at 2.5%. In the 25 years since

1983, real incomes in Australia have risen by

one third, over 30%. The largest increment to

incomes at any time in the twentieth century.

These policies will work just as well for Korea

as they have worked for Australia.

Given that all societies are different, the

variations on the theme in Korea will of course

have to be Korean. But the underlying efficiency

of the changes is guaranteed to lift people more

rapidly up the income scale and to lift Korean

GDP more obviously up the international totem

pole.

It is a very encouraging development indeed,

that one of this country's premier newspapers,

Chosun Ilbo, is committed to these kind of

outcomes and is prepared to meet the

organizational responsibility of promoting a

conference of this kind in promotion of those

outcomes.

Let me congratulate the newspaper, its

management and staff, on this important

initiative.

More History

|

|