|

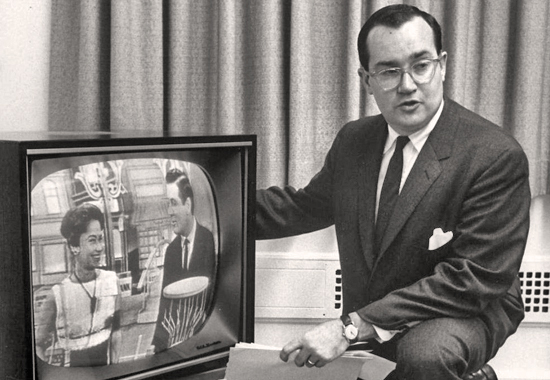

"WHEN TELEVISION IS BAD, NOTHING IS

WORSE." - NEWTON MINOW 1961

Television and the Public Interest

It follows the full text transcript of

Newton Minow's Television and the Public

Interest speech, delivered at

Washington D.C. - May 9, 1961.

|

Thank you for this

opportunity to meet with you today. |

This is my first public address since I took over my new

job. When the New

Frontiersmen rode into town, I locked myself in

my office to do my

homework and get my feet wet. But apparently I

haven't managed to stay

out of hot water. I seem to have detected a

certain nervous apprehension

about what I might say or do when I emerged from

that locked office for

this, my maiden station break.

First, let me begin by dispelling a rumor. I was

not picked for this job

because I regard myself as the fastest draw on

the New Frontier.

Second, let me start a rumor. Like you, I have

carefully read President

Kennedy's messages about the regulatory

agencies, conflict of interest and

the dangers of ex parte contacts. And of course,

we at the Federal

Communications Commission will do our part.

Indeed, I may even suggest

that we change the name of the FCC to The Seven

Untouchables!

It may also come as a surprise to some of you,

but I want you to know

that you have my admiration and respect. Yours

is a most honorable

profession. Anyone who is in the broadcasting

business has a tough row to

hoe. You earn your bread by using public

property. When you work in

broadcasting, you volunteer for public service,

public pressure and public

regulation. You must compete with other

attractions and other investments,

and the only way you can do it is to prove to us

every three years that you

should have been in business in the first place.

I can think of easier ways to make a living.

But I cannot think of more satisfying ways.

I admire your courage—but that doesn't mean I

would make life any

easier for you. Your license lets you use the

public's airwaves as trustees

for 180 million Americans. The public is your

beneficiary. If you want to

stay on as trustees, you must deliver a decent

return to the public—not only

to your stockholders. So, as a representative of

the public, your health and

your product are among my chief concerns.

As to your health: let's talk only of television

today. In 1960 gross

broadcast revenues of the television industry

were over $1,268,000,000;

profit before taxes was $243,900,000—an average

return on revenue of

19.2 per cent. Compare this with 1959, when

gross broadcast revenues

were $1,163,900,000, and profit before taxes was

$222,300,000, an average

return on revenue of 19.1 per cent. So the

percentage increase of total

revenues from 1959 to 1960 was 9 per cent, and

the percentage increase of

profit was 9.7 per cent. This, despite a

recession. For your investors, the

price has indeed been right.

I have confidence in your health.

But not in your product.

It is with this and much more in mind that I

come before you today.

One editorialist in the trade press wrote that

"the FCC of the New

Frontier is going to be one of the toughest

FCC's in the history of broadcast

regulation." If he meant that we intend to

enforce the law in the public

interest, let me make it perfectly clear that he

is right—we do.

If he meant that we intend to muzzle or censor

broadcasting, he is

dead wrong.

It would not surprise me if some of you had

expected me to come

here today and say in effect, "Clean up your own

house or the government

will do it for you."

Well, in a limited sense, you would be

right—I've just said it.

But I want to say to you earnestly that it is

not in that spirit that I

come before you today, nor is it in that spirit

that I intend to serve the FCC.

I am in Washington to help broadcasting, not to

harm it; to strengthen

it, not weaken it; to reward it, not punish it;

to encourage it, not threaten it;

to stimulate it, not censor it.

Above all, I am here to uphold and protect the

public interest.

What do we mean by "the public interest"? Some

say the public

interest is merely what interests the public.

I disagree.

So does your distinguished president, Governor

Collins. In a recent

speech he said, "Broadcasting, to serve the

public interest, must have a soul

and a conscience, a burning desire to excel, as

well as to sell; the urge to

build the character, citizenship and

intellectual stature of people, as well as

to expand the gross national product. . . . By

no means do I imply that

broadcasters disregard the public interest. . .

. But a much better job can be

done, and should be done."

I could not agree more.

And I would add that in today's world, with

chaos in Laos and the

Congo aflame, with Communist tyranny on our

Caribbean doorstep and

relentless pressure on our Atlantic alliance,

with social and economic

problems at home of the gravest nature, yes, and

with technological

knowledge that makes it possible, as our

President has said, not only to

destroy our world but to destroy poverty around

the world—in a time of

peril and opportunity, the old complacent,

unbalanced fare of action-adventure

and situation comedies is simply not good

enough.

Your industry possesses the most powerful voice

in America. It has

an inescapable duty to make that voice ring with

intelligence and with

leadership. In a few years this exciting

industry has grown from a novelty

to an instrument of overwhelming impact on the

American people. It

should be making ready for the kind of

leadership that newspapers and

magazines assumed years ago, to make our people

aware of their world.

Ours has been called the jet age, the atomic

age, the space age. It is

also, I submit, the television age. And just as

history will decide whether

the leaders of today's world employed the atom

to destroy the world or

rebuild it for mankind's benefit, so will

history decide whether today's

broadcasters employed their powerful voice to

enrich the people or debase

them.

If I seem today to address myself chiefly to the

problems of

television, I don't want any of you radio

broadcasters to think we've gone

to sleep at your switch—we haven't. We still

listen. But in recent years

most of the controversies and crosscurrents in

broadcast programming have

swirled around television. And so my subject

today is the television

industry and the public interest.

Like everybody, I wear more than one hat. I am

the Chairman of the

FCC. I am also a television viewer and the

husband and father of other

television viewers. I have seen a great many

television programs that

seemed to me eminently worthwhile, and I am not

talking about the much-bemoaned

good old days of "Playhouse 90" and "Studio

One."

I am talking about this past season. Some were

wonderfully

entertaining, such as "The Fabulous Fifties,"

the "Fred Astaire Show" and

the "Bing Crosby Special"; some were dramatic

and moving, such as

Conrad's "Victory" and "Twilight Zone"; some

were marvelously

informative, such as "The Nation's Future," "CBS

Reports," and "The

Valiant Years." I could list many more—programs

that I am sure everyone

here felt enriched his own life and that of his

family. When television is

good, nothing—not the theater, not the magazines

or newspapers—nothing

is better.

But when television is bad, nothing is worse. I

invite you to sit down

in front of your television set when your

station goes on the air and stay

there without a book, magazine, newspaper,

profit-and-loss sheet or rating

book to distract you—and keep your eyes glued to

that set until the station

signs off. I can assure you that you will

observe a vast wasteland.

You will see a procession of game shows,

violence, audience

participation shows, formula comedies about

totally unbelievable families,

blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism,

murder, Western bad-men,

Western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more

violence and cartoons.

And, endlessly, commercials—many screaming,

cajoling and offending.

And most of all, boredom. True, you will see a

few things you will enjoy.

But they will be very, very few. And if you

think I exaggerate, try it.

Is there one person in this room who claims that

broadcasting can't do

better?

Well, a glance at next season's proposed

programming can give us

little heart. Of seventy-three and a half hours

of prime evening time, the

networks have tentatively scheduled fifty-nine

hours to categories of "action-adventure," situation comedy, variety,

quiz and movies.

Is there one network president in this room who

claims he can't do

better?

Well, is there at least one network president

who believes that the

other networks can't do better?

Gentlemen, your trust accounting with your

beneficiaries is overdue.

Never have so few owed so much to so many.

Why is so much of television so bad? I have

heard many answers:

demands of your advertisers; competition for

ever higher ratings; the need

always to attract a mass audience; the high cost

of television programs; the

insatiable appetite for programming

material—these are some of them.

Unquestionably these are tough problems not

susceptible to easy answers.

But I am not convinced that you have tried hard

enough to solve

them.

I do not accept the idea that the present

over-all programming is

aimed accurately at the public taste. The

ratings tell us only that some

people have their television sets turned on, and

of that number, so many are

tuned to one channel and so many to another.

They don't tell us what the

public might watch if they were offered half a

dozen additional choices. A

rating, at best, is an indication of how many

people saw what you gave

them. Unfortunately it does not reveal the depth

of the penetration, or the

intensity of reaction, and it never reveals what

the acceptance would have

been if what you gave them had been better—if

all the forces of art and

creativity and daring and imagination had been

unleashed. I believe in the

people's good sense and good taste, and I am not

convinced that the

people's taste is as low as some of you assume.

My concern with the rating services is not with

their accuracy.

Perhaps they are accurate. I really don't know.

What, then, is wrong with

the ratings? It's not been their accuracy—it's

been their use.

Certainly I hope you will agree that ratings

should have little

influence where children are concerned. The best

estimates indicate that

during the hours of 5 to 6 P.M., 60 per cent of

your audience is composed of

children under twelve. And most young children

today, believe it or not,

spend as much time watching television as they

do in the schoolroom. I

repeat—let that sink in—most young children

today spend as much time

watching television as they do in the

schoolroom. It used to be said that

there were three great influences on a child:

home, school and church.

Today there is a fourth great influence, and you

ladies and gentlemen

control it.

If parents, teachers and ministers conducted

their responsibilities by

following the ratings, children would have a

steady diet of ice cream,

school holidays and no Sunday School. What about

your responsibilities?

Is there no room on television to teach, to

inform, to uplift, to stretch, to

enlarge the capacities of our children? Is there

no room for programs

deepening their understanding of children in

other lands? Is there no room

for a children's news show explaining something

about the world to them

at their level of understanding? Is there no

room for reading the great

literature of the past, teaching them the great

traditions of freedom? There

are some fine children's shows, but they are

drowned out in the massive

doses of cartoons, violence and more violence.

Must these be your

trademarks? Search your consciences and see if

you cannot offer more to

your young beneficiaries, whose future you guide

so many hours each and

every day.

What about adult programming and ratings? You

know, newspaper

publishers take popularity ratings too. The

answers are pretty clear; it is

almost always the comics, followed by the

advice-to-the-lovelorn columns.

But, ladies and gentlemen, the news is still on

the front page of all

newspapers, the editorials are not replaced by

more comics, the newspapers

have not become one long collection of advice to

the lovelorn. Yet

newspapers do not need a license from the

government to be in business—

they do not use public property. But in

television—where your

responsibilities as public trustees are so

plain—the moment that the ratings

indicate that Westerns are popular, there are

new imitations of Westerns on

the air faster than the old coaxial cable could

take us from Hollywood to

New York. Broadcasting cannot continue to live

by the numbers. Ratings

ought to be the slave of the broadcaster, not

his master. And you and I both

know that the rating services themselves would

agree.

Let me make clear that what I am talking about

is balance. I believe

that the public interest is made up of many

interests. There are many people

in this great country, and you must serve all of

us. You will get no

argument from me if you say that, given a choice

between a Western and a

symphony, more people will watch the Western. I

like Westerns and

private eyes too—but a steady diet for the whole

country is obviously not

in the public interest. We all know that people

would more often prefer to

be entertained than stimulated or informed. But

your obligations are not

satisfied if you look only to popularity as a

test of what to broadcast. You

are not only in show business; you are free to

communicate ideas as well as

relaxation. You must provide a wider range of

choices, more diversity,

more alternatives. It is not enough to cater to

the nation's whims—you

must also serve the nation's needs.

And I would add this—that if some of you persist

in a relentless

search for the highest rating and the lowest

common denominator, you may

very well lose your audience. Because, to

paraphrase a great American who

was recently my law partner, the people are

wise, wiser than some of the

broadcasters—and politicians—think.

As you may have gathered, I would like to see

television improved.

But how is this to be brought about? By

voluntary action by the

broadcasters themselves? By direct government

intervention? Or how?

Let me address myself now to my role, not as a

viewer, but as

Chairman of the FCC. I could not if I would

chart for you this afternoon in

detail all of the actions I contemplate.

Instead, I want to make clear some of

the fundamental principles which guide me.

1. The people own the air. They own it as

much in prime evening

time as they do at 6 o'clock Sunday morning. For

every hour that the

people give you, you owe them something. I

intend to see that your debt is

paid with service.

2. I think it would be foolish and wasteful

for us to continue

any worn-out wrangle over the problems of

payola, rigged quiz shows, and

other mistakes of the past. There are laws on

the books which we will

enforce. But there is no chip on my shoulder. We

live together in perilous,

uncertain times; we face together staggering

problems; and we must not

waste much time now by rehashing the clichés of

past controversy. To

quarrel over the past is to lose the future.

3. I believe in the free enterprise system.

I want to see

broadcasting improved and I want you to do the

job. I am proud to

champion your cause. It is not rare for American

businessmen to serve a

public trust. Yours is a special trust because

it is imposed by law.

4. I will do all I can to help educational

television. There are still

not enough educational stations, and major

centers of the country still lack

usable educational channels. If there were a

limited number of printing

presses in this country, you may be sure that a

fair proportion of them

would be put to educational use. Educational

television has an enormous

contribution to make to the future, and I intend

to give it a hand along the

way. If there is not a nationwide educational

television system in this

country, it will not be the fault of the FCC.

5. I am unalterably opposed to governmental

censorship. There

will be no suppression of programming which does

not meet with

bureaucratic tastes. Censorship strikes at the

tap root of our free society.

6. I did not come to Washington to idly

observe the squandering

of the public's airwaves. The squandering of our

airwaves is no less

important than the lavish waste of any precious

natural resource. I intend to

take the job of Chairman of the FCC very

seriously. I believe in the gravity

of my own particular sector of the New Frontier.

There will be times

perhaps when you will consider that I take

myself or my job too seriously.

Frankly, I don't care if you do. For I am

convinced that either one takes this

job seriously—or one can be seriously taken.

Now, how will these principles be applied?

Clearly, at the heart of the

FCC's authority lies its power to license, to

renew or fail to renew, or to

revoke a license. As you know, when your license

comes up for renewal,

your performance is compared with your promises.

I understand that many

people feel that in the past licenses were often

renewed pro forma. I say to

you now: renewal will not be pro forma in the

future. There is nothing

permanent or sacred about a broadcast license.

But simply matching promises and performance is

not enough. I

intend to do more. I intend to find out whether

the people care. I intend to

find out whether the community which each

broadcaster serves believes he

has been serving the public interest. When a

renewal is set down for

hearing, I intend—wherever possible—to hold a

well-advertised public

hearing, right in the community you have

promised to serve. I want the

people who own the air and the homes that

television enters to tell you and

the FCC what's been going on. I want the

people—if they are truly

interested in the service you give them—to make

notes, document cases,

tell us the facts. For those few of you who

really believe that the public

interest is merely what interests the public—I

hope that these hearings will

arouse no little interest.

The FCC has a fine reserve of monitors—almost

180 million

Americans gathered around 56 million sets. If

you want those monitors to

be your friends at court—it's up to you.

Some of you may say,

"Yes, but I still do not

know where the line is

between a grant of a renewal and the hearing you

just spoke of." My

answer is: why should you want to know how close

you can come to the

edge of the cliff? What the Commission asks of

you is to make a

conscientious good-faith effort to serve the

public interest. Everyone of you

serves a community in which the people would

benefit by educational,

religious, instructive or other public service

programming. Every one of

you serves an area which has local needs—as to

local elections,

controversial issues, local news, local talent.

Make a serious, genuine effort

to put on that programming. When you do, you

will not be playing

brinkmanship with the public interest.

What I've been saying applies to broadcast

stations. Now a station

break for the networks:

You know your importance in this great industry.

Today, more than

one-half of all hours of television station

programming comes from the

networks; in prime time, this rises to more than

three-fourths of the

available hours.

You know that the FCC has been studying network

operations for

some time. I intend to press this to a speedy

conclusion with useful results.

I can tell you right now, however, that I am

deeply concerned with

concentration of power in the hands of the

networks. As a result, too many

local stations have foregone any efforts at

local programming, with little

use of live talent and local service. Too many

local stations operate with

one hand on the network switch and the other on

a projector loaded with

old movies. We want the individual stations to

be free to meet their legal

responsibilities to serve their communities.

I join Governor Collins in his views so well

expressed to the

advertisers who use the public air. I urge the

networks to join him and

undertake a very special mission on behalf of

this industry: you can tell

your advertisers, "This is the high quality we

are going to serve—take it or

other people will. If you think you can find a

better place to move

automobiles, cigarettes and soap—go ahead and

try."

Tell your sponsors to be less concerned with

costs per thousand and

more concerned with understanding per millions.

And remind your

stockholders that an investment in broadcasting

is buying a share in public

responsibility.

The networks can start this industry on the road

to freedom from the

dictatorship of numbers.

But there is more to the problem than network

influences on stations

or advertiser influences on networks. I know the

problems networks face in

trying to clear some of their best programs—the

informational programs

that exemplify public service. They are your

finest hours, whether

sustaining or commercial, whether regularly

scheduled or special; these are

the signs that broadcasting knows the way to

leadership. They make the

public's trust in you a wise choice.

They should be seen. As you know, we are

readying for use new

forms by which broadcast stations will report

their programming to the

Commission. You probably also know that special

attention will be paid in

these reports to public service programming. I

believe that stations taking

network service should also be required to

report the extent of the local

clearance of network public service programming,

and when they fail to

clear them, they should explain why. If it is to

put on some outstanding

local program, this is one reason. But, if it is

simply to carry some old

movie that is an entirely different matter. The

Commission should consider

such clearance reports carefully when making up

its mind about the

licensee's over-all programming.

We intend to move—and as you know, indeed the

FCC was rapidly

moving in other new areas before the new

Administration arrived in

Washington. And I want to pay my public respects

to my very able

predecessor, Fred Ford, and my colleagues on the

Commission who have

welcomed me to the FCC with warmth and

cooperation.

We have approved an experiment with pay TV, and

in New York we

are testing the potential of UHF broadcasting.

Either or both of these may

revolutionize television. Only a foolish prophet

would venture to guess the

direction they will take, and their effect. But

we intend that they shall be

explored fully—for they are part of

broadcasting's new frontier.

The questions surrounding pay TV are largely

economic. The

questions surrounding UHF are largely

technological. We are going to give

the infant pay TV a chance to prove whether it

can offer a useful service;

we are going to protect it from those who would

strangle it in its crib.

As for UHF, I'm sure you know about our test in

the canyons of New

York City. We will take every possible positive

step to break through the

allocations barrier into UHF. We will put this

sleeping giant to use, and in

the years ahead we may have twice as many

channels operating in cities

where now there are only two or three. We may

have a half-dozen

networks instead of three.

I have told you that I believe in the free

enterprise system. I believe

that most of television's problems stem from

lack of competition. This is

the importance of UHF to me: with more channels

on the air, we will be

able to provide every community with enough

stations to offer service to

all parts of the public. Programs with a

mass-market appeal required by

mass-product advertisers certainly will still be

available. But other stations

will recognize the need to appeal to more

limited markets and to special

tastes. In this way we can all have a much wider

range of programs.

Television should thrive on this competition—and

the country should

benefit from alternative sources of service to

the public. And, Governor

Collins, I hope the NAB will benefit from many

new members.

Another, and perhaps the most important,

frontier: television will

rapidly join the parade into space.

International television will be with us

soon. No one knows how long it will be until a

broadcast from a studio in

New York will be viewed in India as well as in

Indiana, will be seen in the

Congo as it is seen in Chicago. But as surely as

we are meeting here today,

that day will come—and once again our world will

shrink.

What will the people of other countries think of

us when they see our

Western bad-men and good men punching each other

in the jaw in between

the shooting? What will the Latin American or

African child learn of

America from our great communications industry?

We cannot permit

television in its present form to be our voice

overseas.

There is your challenge to leadership. You must

reexamine some

fundamentals of your industry. You must open

your minds and open your

hearts to the limitless horizons of tomorrow.

I can suggest some words that should serve to

guide you:

Television and all who participate in it are

jointly accountable

to the American public for respect for the

special needs of

children, for community responsibility, for the

advancement of

education and culture, for the acceptability of

the program

materials chosen, for decency and decorum in

production, and

for propriety in advertising. This

responsibility cannot be

discharged by any given group of programs, but

can be

discharged only through the highest standards of

respect for the

American home, applied to every moment of every

program

presented by television.

Program materials should enlarge the horizons of

the viewer,

provide him with wholesome entertainment, afford

helpful

stimulation, and remind him of the

responsibilities which the

citizen has toward his society.

These words are not mine. They are yours. They

are taken literally

from your own Television Code. They reflect the

leadership and aspirations

of your own great industry. I urge you to

respect them as I do. And I urge

you to respect the intelligent and farsighted

leadership of Governor LeRoy

Collins and to make this meeting a creative act.

I urge you at this meeting

and, after you leave, back home, at your

stations and your networks, to

strive ceaselessly to improve your product and

to better serve your viewers,

the American people.

I hope that we at the FCC will not allow

ourselves to become so

bogged down in the mountain of papers, hearings,

memoranda, orders and

the daily routine that we close our eyes to the

wider view of the public

interest. And I hope that you broadcasters will

not permit yourselves to

become so absorbed in the chase for ratings,

sales and profits that you lose

this wider view. Now more than ever before in

broadcasting's history the

times demand the best of all of us.

We need imagination in programming, not

sterility; creativity, not

imitation; experimentation, not conformity;

excellence, not mediocrity.

Television is filled with creative, imaginative

people. You must strive to set

them free.

Television in its young life has had many hours

of greatness—its "Victory at Sea," its Army-McCarthy hearings,

its "Peter Pan," its "Kraft

Theater," its "See It Now," its "Project 20,"

the World Series, its political

conventions and campaigns, the Great Debates—and

it has had its endless

hours of mediocrity and its moments of public

disgrace. There are

estimates that today the average viewer spends

about 200 minutes daily

with television, while the average reader spends

thirty-eight minutes with

magazines and forty minutes with newspapers.

Television has grown faster

than a teenager, and now it is time to grow up.

What you gentlemen broadcast through the

people's air affects the

people's taste, their knowledge, their opinions,

their understanding of

themselves and of their world. And their future.

The power of instantaneous sight and sound is

without precedent in

mankind's history. This is an awesome power. It

has limitless capabilities

for good—and for evil. And it carries with it

awesome responsibilities—

responsibilities which you and I cannot escape.

In his stirring Inaugural Address, our President

said, "And so, my

fellow Americans: ask not what your country can

do for you—ask what

you can do for your country."

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Ask not what broadcasting can do for you—ask

what you can do for

broadcasting.

I urge you to put the people's airwaves to the

service of the people

and the cause of freedom. You must help prepare

a generation for great

decisions. You must help a great nation fulfill

its future.

Do this, and I pledge you our help.

More History

|