|

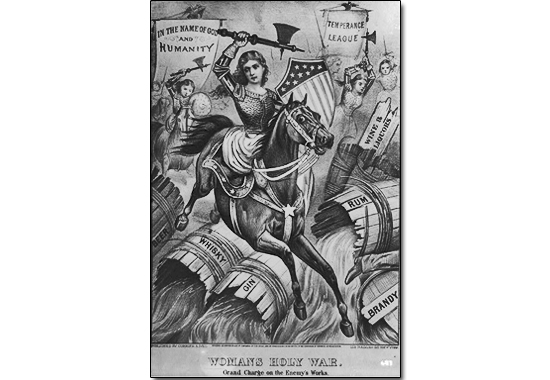

WOMAN'S HOLY WAR, GRAND CHARGE ON

THE ENEMY'S WORKS.

Temperance and Women's Rights

It follows the full text transcript of

Elizabeth Cady Stanton's Temperance and

Women's Rights

speech, delivered at Rochester, New York — June 1, 1853.

|

A little more than

one year ago, |

in this same hall,

we formed the first Woman's State Temperance

Society. We believed that the time had come for

woman to speak on this question, and to insist

on her right to be heard in the councils of

Church and State.

It was proposed at

that time that we, instead of forming a society,

should go en masse into the Men's State

Temperance Society. We were assured that in

becoming members by paying the sum of $1, we

should thereby secure the right to speak and

vote in their meetings.

We who had watched

the jealousy with which man had ever eyed the

slow aggressions of woman, warned you against

the insidious proposition made by agents from

that Society. We told you they would no doubt

gladly receive the dollar, but that you would

never be allowed to speak or vote in their

meetings.

Many of you

thought us suspicious and unjust toward the

temperance men of the Empire State. The fact

that Abby Kelly had been permitted to speak in

one of their public meetings was brought up as

an argument by some agent of that Society to

prove our fears unfounded. We suggested that she

spoke by favor and not right, and our right

there as equals to speak and vote, we well knew

would never be acknowledged. A long debate saved

you from that false step, and our predictions

have been fully realized in the treatment our

delegates received at the annual meeting held at

Syracuse last July, and at the recent Brick

Church meeting in New York.

In forming our Society, the mass of us being

radical and liberal, we left our platform free;

we are no respecters of persons, all are alike

welcome here without regard to sect, sex, color,

or caste. There have been, however, many

objections made to one feature in our

Constitution, and that is, that although we

admit men as members with equal right to speak

in our meetings, we claim the offices for women

alone. We felt, in starting, the necessity of

throwing all the responsibility on woman, which

we knew she never would take, if there were any

men at hand to think, act, and plan for her.

The result has

shown the wisdom of what seemed so objectionable

to many. It was, however, a temporary expedient,

and as that seeming violation of man's rights

prevents some true friends of the cause from

becoming members of our Society, and as the

officers are now well skilled in the practical

business of getting up meetings, raising funds,

etc., and have fairly learned bow to stand and

walk alone, it may perhaps be safe to raise man

to an entire equality with ourselves, hoping,

however, that he will modestly permit the women

to continue the work they have so successfully

begun. I would suggest, therefore, that after

the business of the past year be disposed of,

this objectionable feature of our Constitution

be brought under consideration.

Our experience thus far as a Society has been

most encouraging. We number over two thousand

members. We have four agents who have traveled

in various parts of the State, and I need not

say what is well known to all present, that

their labors thus far have given entire

satisfaction to the Society and the public. I

was surprised and rejoiced to find that women,

without the least preparation or experience, who

had never raised their voices in public one year

ago, should with so much self-reliance, dignity,

and force, enter at once such a field of labor,

and so ably perform the work.

In the metropolis

of our country, in the capital of our State,

before our Legislature, and in the country

schoolhouse, they have been alike earnest and

faithful to the truth. In behalf of our Society,

I thank you for your unwearied labors during the

past year. In the name of humanity, I bid you go

on and devote yourselves humbly to the cause you

have espoused. The noble of your sex everywhere

rejoice in your success, and feel in themselves

a new impulse to struggle upward and onward; and

the deep, though silent gratitude that ascends

to Heaven from the wretched outcast, the wives,

the mothers, and the daughters of brutal

drunkards, is well known to all who have

listened to their tales of woo, their bitter

experience, the dark, sad passages of their

tragic lives.

I hope this, our first year, is prophetic of a

happy future of strong united, and energetic

action among the women of our State. If we are

sincere and earnest in our love of this cause,

in our devotion to truth, in our desire for the

happiness of the race, we shall ever lose sight

of self; each soul will, in a measure, forget

its own individual interests in proclaiming

great principles of justice and right. It is

only a true, a deep, and abiding love of truth,

that can swallow up all petty jealousies,

envies, discords, and dissensions, and make us

truly magnanimous and self-sacrificing. We have

every reason to think, from reports we hear on

all sides, that our Society has given this cause

a new impulse. And if the condition of our

treasury is a test, we have abundant reason to

believe that in the hearts of the people we are

approved, and that by their purses we shall be

sustained.

It has been objected to our Society that we do

not confine ourselves to the subject of

temperance, but talk too much about woman's

rights, divorce, and the Church. It could be

easily shown how the consideration of this great

question carries us legitimately into the

discussion of these various subjects. One class

of minds would deal with effects alone. Another

would inquire into causes. The work of the

former is easily perceived and quickly done;

that of the latter requires deep thought, great

patience, much time, and a wise self-denial.

Our physicians of

the present day are a good type of the mass of

our reformers. They take out cancers, cut off

tonsils, drive the poison which nature has

wisely thrown to the surface, back again, quiet

unsteady nerves with valerian, and by means of

ether infuse an artificial courage Into a

patient that he may bravely endure some painful

operation. It requires but little thought to

feel that the wise physician who shall trace out

the true causes of suffering; who shall teach us

the great, immutable laws of life and health;

who shall show us how and where in our every-day

life, we are violating these laws, and the true

point to begin the reform, is doing a much

higher, broader, and deeper work than he who

shall bend all his energies to the temporary

relief of suffering.

Those temperance

men or women whose whole work consists in

denouncing rum-sellers, appealing to

legislatures, eulogizing Neal Dow, and shouting

Maine Law, are superficial reformers, mere

surface-workers. True, this outside work is

well, and must be done; let those who see no

other do this, but let them lay no hindrances in

the way of that class of mind, who, seeing in

our present false social relations the causes of

the moral deformities of the race, would fain

declare the immutable laws that govern mind as

well as matter, and point out the true causes of

the evils we see about us, whether lurking under

the shadow of the altar, the sacredness of the

marriage institution, or the assumed superiority

of man.

We have been obliged to preach woman's rights,

because many, instead of listening to what we

had to say on temperance, have questioned the

right of a woman to speak on any subject. In

courts of justice and legislative assemblies, if

the right of the speaker to be there is

questioned, all business waits until that point

is settled. Now, it is not settled in the mass

of minds that woman has any rights on this

footstool, and much less a right to stand on an

even pedestal with man, look him in the face as

an equal, and rebuke the sins of her day and

generation. Let it be clearly understood, then,

that we are a woman's rights Society; that we

believe it is woman's duty to speak whenever she

feels the impression to do so; that it is her

right to be present in all the councils of

Church and State. The fact that our agents are

women, settles the question of our character on

this point.

Again, in discussing the question of temperance,

all lecturers, from the beginning, have made

mention of the drunkards' wives and children, of

widows' groans and orphans' tears; shall these

classes of sufferers be introduced but as themes

for rhetorical flourish, as pathetic touches of

the speaker's eloquence; shall we passively shed

tears over their condition, or by giving them

their rights, bravely open to them the doors of

escape from a wretched and degraded life? Is it

not legitimate in this to discuss the social

degradation, the legal disabilities of the

drunkard's wife?

If, in showing her

wrongs, we prove the right of all womankind to

the elective franchise, to a fair representation

in the government, to the right in criminal

cases to be tried by peers of her own choosing,

shall it be said that we transcend the bounds of

our subject? If in pointing out her social

degradation, we show you how tile present laws

outrage the sacredness of the marriage

institution; if in proving to you that justice

and mercy demand a legal separation from

drunkards, we grasp the higher idea that a unity

of soul alone constitutes and sanctifies true

marriage, and that any law or public sentiment

that forces two immortal, high-born souls to

live together as husband and wife, unless held

there by love, is false to God and humanity; who

shall say that tile discussion of this question

does not lead us legitimately into the

consideration of tile important subject of

divorce?

But why attack the Church ? We do not attack the

Church. We defend ourselves merely against its

attacks. It is true that tile Church and

reformers have always been in an antagonistic

position from the time of Luther down to our own

day, and will continue to be until the

devotional and practical types of Christianity

shall be united in one liarinonious whole.

To those who see

the philosophy of this position, there seems to

be no cause for fearful forebodings or helpless

regret. By the light of reason and truth, in

good time, all these seeming differences will

pass away. I have no special fault to find with

that part of humanity that gathers into our

churches; to me, human nature seems to manifest

itself in very much the same way in the Church

and out of it. Go through any community you

please-into the nursery, kitchen, the parlor,

the places of merchandise, the market-place, and

exchange, and who can tell the church member

from the outsider? I see no reason why we should

expect more of them than other men.

Why, say you, they

lay claim to greater holiness, to more rigid

creeds, to a belief in a sterner God, to a

closer observance of forms? The Bible with them

is the rule of life, the foundation of faith,

and why should we not look to them for patterns

of purity, goodness, and truth above all other

men?

I deny the

assumption.

Reformers from all

sides claim for themselves a higher position

than the Church. Our God is a god of justice,

mercy, and truth. Their God sanctions violence,

oppression, and wine-bibbing, and winks at gross

moral delinquencies.

Our Bible commands

us to love our enemies; to resist not evil; to

break every yoke and let the oppressed go free,

and makes a noble life of more importance than a

stern faith. Their Bible permits war, slavery,

capital punishment, and makes salvation depend

on faith and ordinances.

In their creed it

is a sin to dance, to pick up sticks on the

Sabbath day, to go to the theater, or large

parties during Lent, to read a notice of any

reform meeting from the altar, or permit a woman

to speak in the church. In our creed it is a sin

to hold a slave; to hang a man on the gallows;

to make war on defenseless nations, or to sell

rum to a weak brother, and rob the widow and the

orphan of a protector and a home.

Thus may we write

out some of our differences, but from the

similarity in the conduct of the human family,

it is fair to infer that our differences are

more intellectual than spiritual, and the great

truths we hear so clearly uttered on all sides,

have been incorporated as vital principles into

the inner life of but few indeed.

We must not expect the Church to leap en

masse to a higher position. She sends forth

her missionaries of truth one by one. All of our

reformers have, in a measure, been developed in

the Church, and all our reforms have started

there. The advocates and opposers of the reforms

of our day, have grown up side by side,

partaking of the same ordinances and officiating

at the same altars; but one, by applying more

fully his Christian principles to life, and

pursuing an admitted truth to its legitimate

results, has unwittingly found himself in

antagonism with his brother.

Belief is not voluntary, and change is the

natural result of growth and development. We

would fain have all church members sons and

daughters of temperance. But if the Church, in

her wisdom, has made her platform so broad that

wine-bibbers and rum-sellers may repose in ease

thereon, we who are always preaching liberality

ought to be the last to complain.

More History

|

|