|

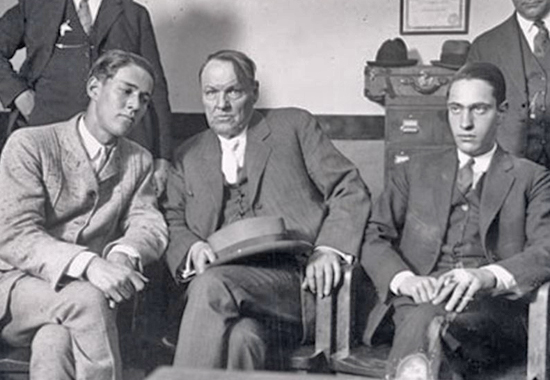

LEFT TO RIGHT: LOEB, DARROW, AND

LEOPOLD - CHICAGO 1924

The Book of Love

Go here for more about

Clarence Darrow.

Clarence Darrow.

Go here for more about

Clarence Darrow's closing argument.

Clarence Darrow's closing argument.

It follows the full text transcript of

Clarence Darrow's closing argument in the case

Illinois versus Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, delivered at

Chicago, Illinois - August 22, 1924.

This is page 1 of 2. Go here for

page 2 of this speech.

page 2 of this speech.

|

Your Honor, it has

been almost three months since the great

responsibility of this case was assumed by my

associates and myself. |

It has been three

months of great anxiety. A burden which I gladly

would have been spared excepting for my feelings

of affection toward some of the members of one

of these unfortunate families.

Our anxiety over this case has not been due to

the facts that are connected with this most

unfortunate affair, but to the almost unheard of

publicity it has received; to the fact that

newspapers all over this country have been

giving it space such as they have almost never

before given to any case. The fact that day

after day the people of Chicago have been

regaled with stories of all sorts about it,

until almost every person has formed an opinion.

And when the public is interested and demands a

punishment, no matter what the offense, great or

small, it thinks of only one punishment, and

that is death. It may not be a question that

involves the taking of human life; it may be a

question of pure prejudice alone; but when the

public speaks as one man, it thinks only of

killing.

It was announced that there were millions of

dollars to be spent on this case. Wild and

extravagant stories were freely published as

though they were facts. Here was to be an effort

to save the lives of two boys by the use of

money in fabulous amounts. We announced to the

public that no excessive use of money would be

made in this case, neither for lawyers nor for

psychiatrists, or in any other way. We have

faithfully kept that promise. The psychiatrists

are receiving a per diem, and only a per diem,

which is the same as is paid by the state. The

attorneys, at their own request, have agreed to

take such amount as the officers of the Chicago

Bar Association may think proper in this case.

If we fail in this defense it will not be for

lack of money. It will be on account of money.

Money has been the most serious handicap that we

have met. There are times when poverty is

fortunate.

I insist, Your Honor, that had this been the

case of two boys of these defendants' age,

unconnected with families of great wealth, there

is not a state's attorney in Illinois who could

not have consented at once to a plea of guilty

and a punishment in the penitentiary for life.

Not one. No lawyer could have justified any

other attitude. No prosecution could have

justified it.

We are here with the lives of two boys

imperiled, with the public aroused. For what?

Because, unfortunately, the parents have money.

Nothing else.

I have heard in the last six weeks nothing but

the cry for blood. I have heard from the office

of the state's attorney only ugly hate. I have

heard precedents quoted which would be a

disgrace to a savage race. I have seen a court

urged almost to the point of threats to hang two

boys, in the face of science, in the face of

philosophy, in the face of humanity, in the face

of experience, in the face of all the better and

more humane thought of the age.

Why, Mr. Savage [one of the prosecutors] says

age makes no difference, and that if this court

should do what every other court in Illinois has

done since its foundation, and refuse to

sentence these boys to death, none else would

ever be hanged in Illinois.

Well, I can imagine some results worse than

that. So long as this terrible tool is to be

used for a plaything, without thought or

consideration, we ought to get rid of it for the

protection of human life.

Now, Your Honor, Mr. Savage, in as cruel a

speech as he knew how to make, said to this

court that we pled guilty because we are afraid

to do anything else.

Your Honor, that is true.

It was not correct that we would have defended

these boys in this court; we believe we have

been fair to the public. Anyhow, we have tried,

and we have tried under terribly hard

conditions.

We have said to the public and to this court

that neither the parents, nor the friends, nor

the attorneys would want these boys released.

Unfortunate though it be, it is true, and those

the closest to them know perfectly well that

they should not be released, and that they

should be permanently isolated from society. We

are asking this court to save their lives, which

is the least and the most that a judge can do.

We did plead guilty before Your Honor because we

were afraid to submit our cause to a jury.

I can tell Your Honor why. I have found that

years and experience with life tempers one's

emotions and makes him more understanding of his

fellowman. When my friend Savage is my age, or

even yours, he will read his address to this

court with horror. I am aware that as one grows

older he is less critical. He is not so sure. He

is inclined to make some allowance for his

fellowman. I am aware that a court has more

experience, more judgment, and more kindliness

than a jury.

Your Honor, it may be hardly fair to the court,

I am aware that I have helped to place a serious

burden upon your shoulders. And at that, I have

always meant to be your friend, but this was not

an act of friendship. I know perfectly well that

where responsibility is divided by twelve, it is

easy to say: "Away with him."

But, Your Honor, if these boys hang, you must do

it. There can be no division of responsibility

here. You can never explain that the rest

overpowered you. It must be by your deliberate,

cool, premeditated act, without a chance to

shift responsibility. It was not a kindness to

you. We placed this responsibility on your

shoulders because we were mindful of the rights

of our clients, and we were mindful of the

unhappy families who have done no wrong.

Your Honor will never thank me for unloading

this responsibility upon you, but you know that

I would have been untrue to my clients if had

not concluded to take this chance before court,

instead of submitting it to a poisoned jury in

the city of Chicago. I did it knowing that it

would be an unheard of thing for any court, no

matter who, to sentence these boys to death.

Your Honor, I must for a moment criticize the

arguments that have preceded me. I can sum up

the prosecutor's arguments in a minute: cruelly,

dastardly, premeditated, fiendish, abandoned,

and malignant heart.

Now, that is what I have listened to for three

days against two minors, two children, who have

no right to sign a note or take a deed.

Cowardly? Well, I don't know. Let me tell you

something that I think is cowardly, whether

their acts were or not. Here is Dickie Loeb, and

Nathan Leopold, and the state objects to anybody

calling one "Dickie" and the other "Babe"

although everybody does, but they think they can

hang them easier if their names are Richard and

Nathan, so, we will call them Richard and

Nathan. Eighteen and nineteen years old at the

time of the homicide. Here are three officers

watching them. They are led out and in [to] this

jail and across the bridge waiting to be hanged.

Not a chance to get away. Handcuffed when they

get out of this room. Not a chance. Penned like

rats in a trap; and for a lawyer with

physiological eloquence to wave his fist in

front of their faces and shout "Cowardly!" does

not appeal to me as a brave act.

Cold-blooded? Why? Because they planned, and

schemed. Yes. But here are the officers of

justice, so-called, with all the power of the

state, and he said they played for five cents a

point. Now, I trust Your Honor knows better than

I do how much of a game that would be. At poker

I might guess, but I know little about bridge.

But what else? He said that in a game one of

them lost $90 to the other one. They were

playing again each other, and one of them lost

$90? Ninety dollars! Their joint money was just

the same; and there is not another word of

evidence in this case to sustain the statement

of Mr. Crowe, who pleads to hang these boys.

Your Honor, is it not trifling?

It would be trifling, excepting, Your Honor,

that we are dealing in human life. And we are

dealing in more than that; we are dealing in the

future fate of two families. We are talking of

placing a blot upon two houses that do not

deserve it. And all that they can get out of

their imagination is that there was a game of

bridge and one lost $90 to the other, and

therefore they went out and committed murder.

Your Honor knows that it is utterly absurd. The

evidence was absolutely worthless. The statement

was made out of whole cloth, and Mr. Crowe felt

like that policeman who came in here and

perjured himself, as I will show you later on,

who said that when he was talking with Nathan

Leopold Jr., he told him the public was not

satisfied with the motive. I wonder if the

public is satisfied with the motive? If there is

any person in Chicago who; under the evidence in

this case would believe that this was the

motive, then he is stupid. That is all I have to

say for him, just plain stupid.

But let us go further than that. Who were these

two boys? And how did it happen?

On a certain day they killed poor little Robert

Franks. They were not to get $10,000; they were

to get $5,000 if it worked; that is, $5,000

each. Neither one could get more than five, and

either one was risking his; neck in the job. So

each one of my clients was risking his neck for

$5,000, if it had anything to do with it, which

it did not.

Did they need the money? Why at this very time,

and a few months before, Dickie Loeb had $3,000

[in his] checking account in the bank. Your

Honor, I would be ashamed to talk about this

except that in all apparent seriousness they are

asking to kill these two boys on the strength of

this flimsy foolishness. At that time, Richard

Loeb had a three-thousand-dollar checking

account in the bank. He had three Liberty Bonds,

one of which was past due, and the interest on

each of them had not been collected for three

years. And yet they would ask to hang him on the

theory that he committed this murder because he

needed money.

How about Leopold? Leopold was in regular

receipt of $125 a month; he had an automobile;

paid nothing for board and clothes, and

expenses; he got money whenever he wanted it,

and he had arranged to go to Europe and had

bought his ticket and was going to leave about

the time he was arrested in this case. He passed

his examination for the Harvard Law School, and

was going to take a short trip to Europe before

it was time for him to attend the fall term. His

ticket had been bought, and his father was to

give him $3,000 to make the trip. Your Honor,

jurors sometimes make mistakes, and courts do,

too. If on this evidence the court is to

construe a motive out of this case, then I

insist that a motive could be construed out of

any set of circumstances and facts that might be

imagined.

The boys had been reared in luxury, they had

never been denied anything; no want or desire

left unsatisfied; no debts; no need of money;

nothing. And yet they murdered a little boy,

against whom they had nothing in the world,

without malice, without reason, to get $5,000

each. All right. All right, Your Honor, if the

court believes it, if anyone believes it, I

can't help it. That is what this case rests on.

It could not stand up a minute without motive.

without it, it was the senseless act of immature

and diseased children, as it was; a senseless

act of children, wandering around in the dark

and moved by some motion, that we still perhaps

have not the knowledge or the insight into life

to thoroughly understand.

Now, let me go on with it. What else do they

claim?

It has been argued to this court that you can do

no such thing as to grant the almost divine

favor of saving the lives of two boys, that it

is against the law, that the penalty for murder

is death; and this court, who, in the fiction of

the lawyers and the judges, forgets that he is a

human being and becomes a court, pulseless,

emotionless, devoid of those common feelings

which alone make men; that this court as a human

machine must hang them because they killed.

Now, let us see. I do not need to ask mercy from

this court for these clients, nor for anybody

else, nor for myself; though I have never yet

found a person who did not need it. But I do not

ask mercy for these boys. Your Honor may be as

strict in the enforcement of the law as you

please and you cannot hang these boys. You can

only hang them because back of the law and back

of justice and back of the common instincts of

man, and back of the human feeling for the

young, is the hoarse voice of the mob which

says, "Kill." I need ask nothing. What is the

law of Illinois? If one is found guilty of

murder in the first degree by a jury, or if he

pleads guilty before a court, the court or jury

may do one of three things: he may hang, he may

imprison for life, or he may imprison for a term

of not less than fourteen years. Now, why is

that the law? Does it follow from the statute

that a court is bound to ascertain the

impossible, and must necessarily measure the

degrees of guilt? Not at all. He may not be able

to do it. A court may act from any reason or ,

from no reason. A jury may fix anyone of these

penalties as they separate. Why was this law

passed? Undoubtedly in recognition of the

growing feeling in all the forward-thinking

people of the United States against capital

punishment. Undoubtedly, through the deep

reluctance of courts and juries to take human

life.

Without any reason whatever, without any facts

whatever, Your Honor must make the choice, and

you have the same right to make one choice as

another. It is Your Honor's province; you may do

it, and I need ask nothing in order to have you

do it. There is the statute. But there is more

than that in this case.

We have sought to tell this court why he should

not hang these boys. We have sought to tell this

court, and to make this court believe, that they

were diseased of mind, and that they were of

tender age. However, before I discuss that, I

ought to say another word in reference to the

question of motive in this case. If there was no

motive, except the senseless act of immature

boys, then of course there is taken from this

case all of the feeling of deep guilt upon the

part of these defendants.

There was neither cruelty to the deceased,

beyond taking his life, nor was there any depth

of guilt and depravity on the part of the

defendants, for it was a truly motiveless act,

without the slightest feeling of hatred or

revenge, done by a couple of children for no

sane reason.

But, Your Honor, we have gone further than that,

and we have sought to show you, as I think we

have, the condition of these boys' minds. Of

course it is not an easy task to find out the

condition of another person's mind. Now, I was

about to say that it needs no expert, it needs

nothing but a bare recitation of these facts,

and a fair consideration of them, to convince

any human being that this was the act of

diseased brains.

But let's get to something stronger than that.

Were these boys in their right minds? Here were

two boys with good intellect, one eighteen and

one nineteen. They had all the prospects that

life could hold out for any of the young; one a

graduate of Chicago and another of Ann Arbor;

one who had passed his examination for the

Harvard Law School and was about to take a trip

in Europe, another who had passed at Ann Arbor,

the youngest in his class, with $3,000 in the

bank. Boys who never knew what it was to want a

dollar; boys who could reach any position that

was given to boys of that kind to reach; boys of

distinguished and honorable families, families

of wealth and position, with all the world

before them. And they gave it all up for

nothing, for nothing! They took a little

companion of one of them, on a crowded street,

and killed him, for nothing, and sacrificed

everything that could be of value in human life

upon the crazy scheme of a couple of immature

lads.

Now, Your Honor, you have been a boy; I have

been a boy. And we have known other boys. The

best way to understand somebody else is to put

yourself in his place. Is it within the realm of

your imagination that a boy who was right, with

all the prospects of life before him, who could

choose what he wanted, without the slightest

reason in the world would lure a young companion

to his death, and take his place in the shadow

of the gallows?

How insane they are I care not, whether

medically or legally. They did not reason; they

could not reason; they committed the most

foolish, most unprovoked, most purposeless, most

causeless act that any two boys ever committed,

and they put themselves where the rope is

dangling above their heads.

There are not physicians enough in the world to

convince any thoughtful, fair-minded man that

these boys are right. Was their act one of

deliberation, of intellect, or were they driven

by some force such as Dr. White and Dr. Glueck

and Dr. Healy have told this court?

There are only two theories; one is that their

diseased brains drove them to it; the other is

the old theory of possession by devils, and my

friend Marshall could have read you books on

that, too, but it has been pretty well given up

in Illinois. That they were intelligent, sane,

sound, and reasoning is unthinkable. Let me call

Your Honor's attention to another thing.

Why did they kill little Bobby Franks? Not for

money, not for spite; not for hate. They killed

him as they might kill a spider or a fly, for

the experience. They killed him because they

were made that way. Because somewhere in the

infinite processes that go to the making up of

the boy or the man something slipped, and those

unfortunate lads sit here hated, despised,

outcasts, with the community shouting for their

blood. Mr. Savage, with the immaturity of youth

and inexperience, says that if we hang them

there will be no more killing. This world has

been one long slaughterhouse from the beginning

until today, and killing goes on and on and on,

and will forever. Why not read something, why

not study something, why not think instead of

blindly shouting for death?

Kill them. Will that prevent other senseless

boys or other vicious men or vicious women from

killing? No! It will simply call upon every

weak-minded person to do as they have done. I

know how easy it is to I talk about mothers when

you want to do something cruel. But I am

thinking of the others, too. I know that any

mother might be the mother of little Bobby

Franks, who left his home and went to his

school, and who never came back. I know that any

mother might be the mother of Richard Loeb and

Nathan Leopold, just the same. The trouble is

this, that if she is the mother of a Nathan

Leopold or of a Richard Loeb, she has to ask

herself the question: "How come my children came

to be what they are? From what ancestry did they

get this strain? How far removed was the poison

that destroyed their lives? Was I the bearer of

the seed that brings them to death?" Any mother

might be the mother of any of them. But these

two are the victims.

No one knows what will be the fate of the child

he gets or the child she bears; the fate of the

child is the last thing they consider.

I am sorry for the fathers as well as the

mothers, for the fathers who give their strength

and their lives for educating and protecting and

creating a fortune for the boys that they love;

for the mothers who go down into the shadow of

death for their children, who nourish them and

care for them, and risk their lives, that they

may live, who watch them with tenderness and

fondness and longing, and who go down into

dishonor and disgrace for the children that they

love.

All of these are helpless. We are all helpless.

But when you are pitying the father and the

mother of poor Bobby Franks, what about the

fathers and mothers of these two unfortunate

boys, and what about the, unfortunate boys

themselves, and what about all the fathers and

all the mothers and all the boys and all the

girls who tread a dangerous maze in darkness

from birth to death?

Do you think you can cure the hatreds and the

maladjustments of the world by hanging them? You

simply show your ignorance and your hate when

you say it. You may here and there cure hatred

with love and understanding, but you can only

add fuel to the flames by cruelty and hate.

Your Honor, that no human being could have done

what these boys did, excepting through the

operation of a diseased brain. I do not propose

to go through each step of the terrible deed, it

would take too long. But I do want to call the

attention of this court to some of the other

acts of these two boys, in this distressing and

weird homicide; acts which show conclusively

that there could be no reason for their conduct.

I want to come down now to the actions on the

afternoon of the tragedy.

Without any excuse, without the slightest

motive, not moved by money, not moved by passion

or hatred, by nothing except the vague

wanderings of children, about four o'clock in

the afternoon they started out to find somebody

to kill. For nothing.

They went over to the Harvard School. Dick's

little brother was there, on the playground.

Dick went there himself in open daylight, known

by all of them; he had been a pupil there

himself, the school was near his home, and he

looked over the little boys. They first picked

out a little boy named Levinson, and Dick

trailed him around. Now, of course, that is a

hard story. It is a story that shocks one. A boy

bent on killing, not knowing where he would go

or who he would get, but seeking some victim.

Here is a little boy, but the circumstances are

not opportune, and so he fails to get him. Dick

abandons that lead; Dick and Nathan are in the

car, and they see Bobby Franks on the street,

and they call to him to get into the car. It is

about five o'clock in the afternoon, in the long

summer days, on a thickly settled street, built

up with homes, the houses of their friends and

their companions known to everybody, automobiles

appearing and disappearing, and they take him in

the car.

If there had been a question of revenge, yes; if

there had been a question of hate, where no one

cares for his own fate, intent only on

accomplishing his end, yes. But without any

motive or any reason they picked up this little

boy right in sight of their own homes, and

surrounded by their neighbors. They hit him over

the head with a chisel and killed him, and go on

about their business, driving this car within

half a block of Loeb's home, within the same

distance of the Franks's home, drive it past the

neighbors that they knew, in the open highway,

in broad daylight. And still men will say that

they have a bright intellect.

I say again, whatever madness and hate and

frenzy may do to the human mind, there is not a

single person who reasons who can believe that

one of these acts was the act of men, of brains

that were not diseased. There is no other

explanation for it. And had it not been for the

wealth and the weirdness and the notoriety, they

would have been sent to the psychopathic

hospital for examination, and been taken care

of, instead of the state demanding that this

court take the last pound of flesh and the last

drop of blood from two irresponsible lads.

They pull the dead boy into the backseat, and

wrap him in a blanket, and this funeral car

starts on its route. If ever any death car went

over the same route or the same kind of a route

driven by sane people, I have never heard of it,

and I fancy no one else has ever heard of it.

This car is driven for twenty miles. The

slightest accident, the slightest misfortune, a

bit of curiosity, an arrest for speeding,

anything would bring destruction. They go down

the Midway, through the park, meeting hundreds

of machines, in sight of thousands of eyes, with

this dead boy. They go down a thickly populated

street through South Chicago, and then for three

miles take the longest street to go through this

city; built solid with business, buildings,

filled with automobiles backed upon the street,

with streetcars on the track, with thousands of

peering eyes; one boy driving and the other on

the backseat, with the corpse of little Bobby

Franks, the blood streaming from him, wetting

everything in the car.

And yet they tell me that this is sanity; they

tell me that the brains of these boys are not

diseased. Their conduct shows exactly what it

was, and shows that this court has before him

two young men who should be examined in a

psychopathic hospital and treated kindly and

with care. They get through South Chicago, and

they take the regular automobile road down

toward Hammond. They stop at the forks of the

road, and leave little Bobby Franks, soaked with

blood, in the machine, and get their dinner, and

eat it without an emotion or a qualm.

I repeat, you may search the annals of crime,

and you can find no parallel. It is utterly at

variance with every motive, and every act and

every part of conduct that influences normal

people in the commission of crime. There is not

a sane thing in all of this from the beginning

to the end. There was not a normal act in any of

it, from its inception in a diseased brain,

until today, when they sit here awaiting their

doom.

But we are told that they planned. Well, what

does that mean? A maniac plans, an idiot plans,

an animal plans; any brain that functions may

plan. But their plans were the diseased plans of

the diseased mind. Is there any man with an air

of intellect and a decent regard for human life,

and the slightest bit of heart that does not

understand this situation? And still, Your

Honor, on account of its weirdness and its

strangeness, and its advertising, we are forced

to fight. For what? Forced to plead to this

court that two boys, one eighteen and the other

nineteen, may be permitted to live in silence

and solitude and disgrace and spend all their

days in the penitentiary. Asking this court and

the state's attorney to be merciful enough to

let these two boys be locked up in a prison

until they die.

I sometimes wonder if I am dreaming. If in the

first quarter of the twentieth century there has

come back into the hearts of men the hate and

feeling and the lust for blood which possesses

the primitive savage of barbarous lands. What do

they want? Tell me, is a lifetime for the young

boys spent behind prison bars, is that not

enough for this mad act? And is there any reason

why this great public should be regaled by a

hanging? I cannot understand it, Your Honor. It

would be past belief, excepting that to the four

corners of the earth the news of this weird act

has been carried and men have been stirred, and

the primitive has come back, and the intellect

has been stifled, and men have been controlled

by feelings and passions and hatred which should

have died centuries ago.

My friend Savage pictured to you the putting of

this dead boy in this culvert. Well, no one can

minutely describe any killing and not make it

shocking. It is shocking. It is shocking because

we love life and because we instinctively draw

back from death. It is shocking wherever it is

and however it is, and perhaps all death is

almost equally shocking.

But here is the picture of a dead boy, past

pain, when no harm can come to him, put in a

culvert, after taking off his clothes so that

the evidence would be destroyed; and that is

pictured to this court as a reason for hanging.

Well, Your Honor, that does not appeal to me as

strongly as the hitting over the head of little

Robert Franks with a chisel. The boy was dead.

I could say something about the death penalty

that, for some mysterious reason, the state

wants in this case. Why do they want it? To

vindicate the law? Oh, no. The law can be

vindicated without killing anyone else. It might

shock the fine sensibilities of the state's

counsel that this boy was put into a culvert and

left after he was dead, but, Your Honor, I can

think of a scene that makes this pale into

insignificance. I can think, and only think,

Your Honor, of taking two boys, one eighteen and

the other nineteen, irresponsible, weak,

diseased, penning them in a cell, checking off

the days and the hours and the minutes, until

they will be taken out and hanged. Wouldn't it

be a glorious day for Chicago?

Wouldn't it be a glorious triumph for the

state's attorney? Wouldn't it be a great triumph

for justice in this land? Wouldn't it be a

glorious illustration of Christianity and

kindness and charity? I can picture them,

wakened in the gray light of morning, furnished

[with a] suit of clothes' by the state, led to

the scaffold, their feet tied, black caps drawn

over their heads, stood on a trapdoor, the

hangman pressing a spring, so that it gives way

under them; can see them fall through space and

stopped by the rope around their necks.

I am always suspicious of righteous indignation.

Nothing is more cruel than righteous

indignation. To hear young men talk glibly of

justice.

Who knows what it is? Does Mr. Savage know? Does

Mr. Crowe know? Do I know? Does Your Honor know?

Is there any human machinery for finding it out?

Is there any man can weigh me and say what I

deserve?

Can Your Honor? Let us be honest. Can Your Honor

appraise yourself and say what you deserve? Can

Your Honor appraise these two young men and say

what they deserve? Justice must take account of

infinite circumstances which a human being

cannot understand.

These boys left this body down in the culvert

and they came back telephoned home that they

would be too late for supper. Here, surely, was

an act of consideration on the part of Leopold,

telephoning home that he would be late for

supper. Dr. Krohn says he must be able to think

and act because he could do this. But the boy

who through habit would telephone his home that

he would be late for supper had not a tremor or

a thought or a shudder at taking the life of

little Bobby Franks for nothing, and he has not

had one yet. He was in the habit of doing what

he did when he telephoned, that was all; but in

the presence of life and death, and a cruel

death, he had no tremor, and no thought.

They came back. They got their dinner. They

parked the bloody automobile in front of

Leopold's house. They cleaned it to some extent

that night and left it standing in the street in

front of their home. They took it into the

garage the next day and washed it, and the poor

little Dickie Loeb-I shouldn't call him Dickie,

and I shouldn't call him poor, because that

might be playing for sympathy, and you have no

right to ask for sympathy in this world: you

should ask for justice, whatever that may be;

and only the state's attorneys know.

And then in a day or so we find Dick Loeb with

his pockets stuffed with newspapers telling of

the Franks's tragedy. We find him consulting

with his friends in the club, with the newspaper

reporters; and my experience is that the last

person that a conscious criminal associates with

is a reporter. He even shuns them more than he

does a detective, because they are smarter and

less merciful. But he picks up a reporter, and

he tells him he has read a great many detective

stories, and he knows just how this would happen

and that the fellow who telephoned must have

been down on Sixty-third Street, and the way to

find him is to go down on Sixty-third Street and

visit the drugstores, and he would go with him.

And Dick Loeb pilots reporters around the

drugstores where the telephoning was done, and

he talks about it, and he takes the newspapers,

and takes them with him, and he is having a

glorious time. And yet he is "perfectly

oriented," in the language of Dr. Krohn.

"Perfectly oriented." Is there any question

about the condition of his mind? Why was he

doing it? He liked to hear about it. He had done

something that he could not boast of directly,

but he did want to hear other people talk about

it, and he looked around there, and helped them

find the place where the telephone message was

sent out.

Does not the man who knows what he is doing, who

for some reason has been overpowered and commits

what is called a crime, keep as far away from it

as he can? Does he go to the reporters and help

them hunt it out? There is not a single act in

this case that is not the act of a diseased

mind, not one.

Talk about scheming. Yes, it is the scheme of

disease; it is the scheme of infancy; it is the

scheme of fools; it is the scheme of

irresponsibility from the time it was conceived

until the last act in the tragedy.

Now, Your Honor, let me go a little further with

this. I have gone over some of the high spots in

this tragedy. This tragedy has not claimed all

the attention it has had on account of its

atrocity. There are two reasons, and only two

that I can see. First is the reputed extreme

wealth of these families; not only the Loeb and

Leopold families, but the Franks family, and of

course it is unusual. And next is the fact

[that] it is weird and uncanny and motiveless.

That is what attracted the attention of the

world. Many may say now that they want to hang

these boys. But I know that giving the people

blood is something like giving them their

dinner: when they get it they go to sleep. They

may for the time being have an emotion, but they

will bitterly regret it. And I undertake to say

that if these two boys are sentenced to death,

and are hanged on that day, there will be a pall

settle over the people of this land that will be

dark and deep, and at least cover every humane

and intelligent person with its gloom. I wonder

if it will do good. I marveled when I heard Mr.

Savage talk. Mr. Savage tells this court that if

these boys are hanged, there will be no more

murder. Mr. Savage is an optimist. He says that

if the defendants are hanged there will be no

more boys like these. I could give him a sketch

of punishment, punishment beginning with the

brute which killed something because something

hurt it; the punishment the savage; if a person

is injured in the tribe, they must injure

somebody in the other tribe; it makes no

difference who it is, but somebody. If one is

killed his friends or family must kill in

return.

You can trace it all down through the history of

man. You can trace the burnings, the boilings,

the drawings and quarterings, the hangings of

people in England at the crossroads, carving

them up and hanging them, as examples for all to

see.

We can come down to the last century when nearly

two hundred crimes were punishable by death, and

by death in every form; not only hanging that

was too humane, but burning, boiling, cutting

into pieces, torturing in all conceivable forms.

I know that every step in the progress of

humanity has been met and opposed by

prosecutors, and many times by courts. I know

that when poaching and petty larceny was

punishable by death in England, juries refused

to convict. They were too humane to obey the

law; and judges refused to sentence. I know that

when the delusion of witchcraft was spreading

over Europe, claiming its victims by the

millions, many a judge so shaped his cases that

no crime of witchcraft could be punished in his

court. I know that these trials were stopped in

America because juries would no longer convict.

Gradually the laws have been changed and

modified, and men look back with horror at the

hangings and the killings of the past. What did

they find in England? That as they got rid of

these barbarous statutes, crimes decreased

instead of increased; as the criminal law was

modified and humanized, there was less crime

instead of more. I will undertake to say, Your

Honor, that you can scarcely find a single book

written by a student, and I will include all the

works on criminology of the past, that has not

made the statement over and over again that as

the penal code was made less terrible, crimes

grew less frequent.

If these two boys die on the scaffold, which I

can never bring myself to imagine, If they do

die on the scaffold, the details of this will be

spread over the world. Every newspaper in the

United States will carry a full account. Every

newspaper of Chicago will be filled with the

gruesome details. It will enter every home and

every family. Will it make men better or make

men worse? I would like to put that to the

intelligence of man, at least such intelligence

as they have. I would like to appeal to the

feelings of human beings so far as they have fee

lings-- would it make the human heart softer or

would it make hearts harder?

What influence would it have upon the millions

of men who will read it? What influence would it

have upon the millions of women who will read

it, more sensitive, more impressionable, more

imaginative than men? Would it help them if Your

Honor should do what the state begs you to do?

What influence would it have upon the infinite

number of children who will devour its details

as Dickie Loeb has enjoyed reading detective

stories? Would it make them better or would it

make them worse? The question needs no answer.

You can answer it from the human heart. What

influence, let me ask you, will it have for the

unborn babes still sleeping in their mother's

womb? Do I need to argue to Your Honor that

cruelty only breeds cruelty? That hatred only

causes hatred; that if there is any way to

soften this human heart which is hard enough at

its best, if there is any way to kill evil and

hatred and all that goes with it, it is not

through evil and hatred and cruelty; it is

through charity, and love, and understanding.

I am not pleading so much for these boys as I am

for the infinite number of others to follow,

those who perhaps cannot be as well defended as

these have been, those who may go down in the

storm, and the tempest, without aid. It is of

them I am thinking, and for them I am begging of

this court not to turn backward toward the

barbarous and cruel past.

Now, Your Honor, who are these two boys?

Leopold, with a wonderfully brilliant mind;

Loeb, with an unusual intelligence; both from

their very youth, crowded like hothouse plants,

to learn more and more and more. Dr. Krohn says

that they are intelligent. But it takes

something besides brains to make a human being

who can adjust himself to life.

In fact, as Dr. Church and as Dr. Singer

regretfully admitted, brains are not the chief

essential in human conduct. There is no question

about it. The emotions are the urge that make us

live; the urge that makes us work or play, or

move along the pathways of life. They are the

instinctive things. In fact, intellect is a late

development of life. Long before it was evolved,

the emotional life kept the organism in

existence until death. Whatever our action is,

it comes from the emotions, and nobody is

balanced without them.

The intellect does not count so much. The state

put on three alienists and Dr. Krohn. Two of

them, Dr. Patrick and Dr. Church, are

undoubtedly able men. One of them, Dr. Church,

is a man whom I have known for thirty years, and

for whom I have the highest regard.

On Sunday, June 1, before any of the friends of

these boys or their counsel could see them,

while they were in the care of the state's

attorney's office, they brought them in to be

examined by these alienists. I am not going to

discuss that in detail as I may later on. Dr.

Patrick Sail the only thing unnatural he noted

about it was that they had no emotional

reactions. Dr. Church said the same. These are

their alienists, not ours. These boys could tell

this gruesome story without a change of

countenance, without the slightest feelings.

There were no emotional reactions to it. What

was the reason? I do not know. How can I tell

why? I know what causes the emotional life. I

know it comes from the nerves, the muscles, the

endocrine glands, the vegetative system. I know

it is the most important part of life. I know it

is practically left out of some. I know that

without it men cannot live. I know that without

it they cannot act with the rest. I know they

cannot feel what you feel and what I feel; that

they cannot feel the moral shocks which come to

men who are educated and who have not been

deprived of an emotional system or emotional

feelings. I know it, and every person who has

honestly studied this subject knows it as well.

Is Dickey Loeb to blame because out of the

infinite forces that conspired to form him, the

infinite forces that were at work producing him

ages before he was born, that because out of

these infinite combinations he was born without

it? If he is, then there should be a new

definition for justice. Is he to blame for what

he did not have and never had? Is he to blame

that his machine is imperfect? Who is to blame?

I do not know. I have never in my life been

interested so much in fixing blame as I have in

relieving people from blame. I am not wise

enough to fix it. I know that somewhere in the

past that entered into him something missed. It

may be defective nerves. It may be a defective

heart or liver. It may be defective endocrine

glands. I know it is something. I know that

nothing happens in this world without a cause.

There are at least two theories of man's

responsibility. There may be more. There is the

old theory that if a man does something it is

because he willfully, purposely, maliciously,

and with a malignant heart sees fit to do it.

And that goes back to the possession of man by

devils. The old indictments used to read that a

man being possessed of a devil did so and so.

But why was he possessed with the devil? Did he

invite him in? Could he help it? Very few

half-civilized people believe that doctrine

anymore. Science has been at work, humanity has

been at work, scholarship has been at work, and

intelligent people now know that every human

being is the product of the endless heredity

back of him and the infinite environment around

him. He is made as he is and he is the sport of

all that goes before him and is applied to him,

and under the same stress and storm, you would

act one way and I act another, and poor Dickey

Loeb another.

Dr. Church said so and Dr. Singer said so, and

it is the truth. Take a normal boy, Your Honor.

Do you suppose he could have taken a boy into an

automobile without any reason and hit him over

the head and killed him? I might just as well

ask you whether you thought the sun could shine

at midnight in this latitude. It is not a part

of normality. Something was wrong. I am asking

Your Honor not to visit the grave and dire and

terrible misfortunes of Dickey Loeb and Nathan

Leopold upon these two boys. I do not know where

to place it. I know it is somewhere in the

infinite economy of nature, and if I were wise

enough I could find it. I know it is there, and

to say that because they are as they are you

should hang them, is brutality and cruelty, and

savors of the fang and claw.

Now, Your Honor is familiar with Chicago the

same as I am, and I am willing to admit right

here and now that the two ablest alienists in

Chicago are Dr. Church and Dr. Patrick. There

may be abler ones, but we lawyers do not know

them.

And I will go further: if my friend Crowe had

not got to them first, I would have tried to get

them. There is no question about it at all. And

I say that, Your Honor, without casting the

slightest reflection on either of them, for I

really have a high regard for them, and aside

from that a deep friendship for Dr. Church. And

I have considerable regard for Dr. Singer.

We could not get them, and Mr. Crowe was very

wise, and he deserves a great deal of credit for

the industry, the research, and the thoroughness

that he and his staff have used in detecting

this terrible crime. He worked with intelligence

and rapidity. If here and there he trampled on

the edges of the Constitution I am not going to

talk about it here. If he did it, he is not the

first one in that office and probably will not

be the last who will do it, so let that go. A

great many people in this world believe the end

justifies the means. I don't know but that I do

myself And that is the reason I never want to

take the side of the prosecution, because I

might harm an individual. I am sure the state

will live anyhow.

On that Sunday afternoon before we had a chance,

he got in two alienists, Church and Patrick, and

also called Dr. Krohn, and they around hearing

these boys tell their stories, and that is all.

Your Honor they were not holding an examination.

They were holding an inquest and nothing else.

It has not the slightest reference to, or

earmarks of an examination for sanity. It was

just an inquest; a little premature, but still

an inquest.

What is the truth about it? What did Patrick

say? He said that it was not a good opportunity

for examination. What did Church say? I read

from his own book what was necessary for an

examination, and he said that it was not a good

opportunity for an examination. What did Krohn

say? "It was a fine opportunity for an

examination," the best he had ever heard of, or

that ever anybody had, because their souls were

stripped naked. Krohn is not an alienist. He is

an orator. He said, because their souls were

naked to them. Well, if Krohn's was naked, there

would not be much to show. But Patrick and

Church said that the conditions were unfavorable

for an examination, that they never would choose

it, that their opportunities were poor. And yet

Krohn states the contrary. Krohn, who by his own

admissions, for sixteen years has not been a

physician, but has used a license for the sake

of haunting these courts, civil and criminal,

and going up and down the land peddling perjury.

He has told Your Honor what he has done, and

there is scarcely a child on the street who does

not know it, there is not a judge in the court

who does not know it; there is not a lawyer at

the bar who does not know it; there is not a

physician in Chicago who does not know it; and I

am willing to stake the lives of these two boys

on the court knowing it, and I will throw my own

in for good measure. What else did he say, in

which the state's alienists dispute him?

Both of them say that these boys showed no

adequate emotion. Krohn said they did. One boy

fainted. They had been in the hands of the

state's attorney for sixty hours. They had been

in the hands of policemen, lawyers, detectives,

stenographers, inquisitors, and newspapermen for

sixty hours, and one of them fainted. Well, the

only person who is entirely without emotions is

a dead man. You cannot live without breathing

and some emotional responses. Krohn says, "Why,

Loeb had emotion. He was polite; begged our

pardon; got up from his chair"; even Dr. Krohn

knows better than that. I fancy If Your Honor

goes into an elevator where there is a lady he

takes off his hat. Is that out of emotion for

the lady or is it habit? You say, "Please," and

"thank you," because of habit. Emotions haven't

the slightest thing to do with it. Mr. Leopold

has good manners. Mr. Loeb has good manners.

They have been taught them. They have lived

them. That does not mean that they are

emotional. It means training. That is all it

means. And Dr. Krohn knew it.

Krohn told the story of this interview and he

told almost twice as much as the other two men

who sat there and heard it. And how he told it,

how he told it! When he testified my mind

carried me back to the time when I was a kid,

which was some years ago, and we used to eat

watermelons. I have seen little boys take a rind

of watermelon and cover their whole faces with

water, eat it, devour it, and have the time of

their lives, up to their ears in watermelon. And

when I heard Dr. Krohn testify in this case, to

take the blood of these two boys, I could see

his mouth water with the joy it gave him, and he

showed all the delight and pleasure of myself

and my young companions when we ate watermelon.

I can imagine a psychiatrist, a real one who

knows the mechanism of man, who knows life and

its machinery, who knows the misfortunes of

youth, who knows the stress and the strain of

adolescence which comes to every boy and

overpowers so many, who knows the weird

fantastic world that hedges around the life of a

child; I can imagine a psychiatrist who might

honestly think that under the crude definitions

of the law the defendants were sane and knew the

difference between right and wrong.

Without any consideration of the lives and the

trainings of these boys, without any evidence

from experts, I have tried to make a plain

statement of the facts of this case, and I

believe, as I have said repeatedly, that no one

can honestly study the facts and conclude that

anything but diseased minds was responsible for

this terrible act. Let us see how far we can

account for it, Your Honor.

The mind, of course, is an illusive thing.

Whether it exists or not no one can tell. It

cannot be found as you find the brain. Its

relation to the brain and the nervous system is

uncertain. It simply means the activity of the

body, which is coordinated with the brain. But

when we do find from human conduct that we

believe there is a diseased mind, we naturally

speculate on how it came about. And we wish to

find always, if possible, the reason why it is

so. We may find it, we may not find it; because

the unknown is infinitely wider and larger than

the known, both as to the human mind and as to

almost everything else in the universe.

I have tried to study the lives of these two

most unfortunate boys. Three months ago, if

their friends and the friends of the family had

been asked to pick out the most promising lads

of their acquaintance, they probably would have

picked these two boys. With every opportunity,

with plenty of wealth, they would have said that

those two would succeed. In a day, by an act of

madness, all this is destroyed, until

best they can hope for now is a life of silence

and pain, continuing to end of their years.

How did it happen?

Let us take Dickie Loeb first.

I do not claim to know how it happened; I have

sought to find out; I know that something, or

some combination of things, is responsible for

his mad act. I know that there are no accidents

in nature. I know that effect follows cause. I

know that if I were wise enough, and knew enough

about this case, I could lay my finger on the

cause. I will do the best I can, but it is

largely speculation. The child, of course, is

born without knowledge. Impressions are made

upon its mind as it goes along. Dickie Loeb was

a child of wealth and opportunity. Over and over

in this court Your Honor has been asked, and

other courts have been asked, to consider boys

who have no chance; they have been asked to

consider the poor, whose home had: been the

street, with no education and no opportunity in

life, and they have done it, and done it

rightfully.

But Your Honor, it is just as often a great

misfortune to be the child of the rich as it is

to be the child of the poor. Wealth has its

misfortunes. Too much, too great opportunity and

advantage given to a child has its misfortunes.

Can I find what was wrong? I think I can. Here

was a boy at a tender age, placed in the hands

of a governess, intellectual, vigorous, devoted,

with a strong ambition for the welfare of this

boy. He was, pushed in his studies, as plants

are forced in hothouses. He had no pleasures,

such as a boy should have, except as they were

gained by lying and cheating. Now, I am not

criticizing the nurse. I suggest that some day

Your Honor look at her picture. It explains her

fully. Forceful, brooking no Interference, she

loved the boy, and her ambition was that he

should reach the highest perfection. No time to

pause, no time to stop from one book to another,

no time to have those pleasures which a boy

ought to have to create a normal life. And what

happened?

Your Honor, what would happen? Nothing strange

or unusual. This nurse was with him all the

time, except when he stole out at night, from

two to fourteen years of age, and it is

instructive to read her letter to show her

attitude. It speaks volumes; tells exactly the

relation between these two people. He, scheming

and planning as healthy boys would do, to get

out from under her restraint. She, putting

before him the best books, which children

generally do not want; and he, when she was not

looking, reading detective stories, which he

devoured, story after story, in his young life.

Of all of this there can be no question. What is

the result? Every story he read was a story of

crime. We have a statute in this state, passed

only last year, if I recall it, which forbids

minors reading stories of crime. Why? There is

only one reason. Because the legislature in its

wisdom felt that it would produce criminal

tendencies in the boys who read them. The

legislature of this state has given its opinion,

and forbidden boys to read these books. He read

them day after day. He never stopped. While he

was passing through college at Ann Arbor he was

still reading them. When he was a senior he read

them, and almost nothing else.

This is page 1 of

2. Go here for

page 2 of this speech.

page 2 of this speech.

More History

|

|