|

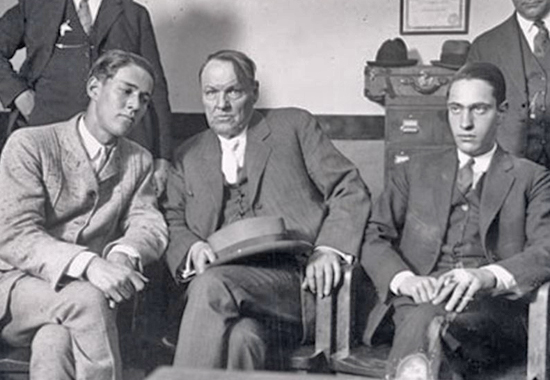

LEFT TO RIGHT: LOEB, DARROW, AND

LEOPOLD - CHICAGO 1924

The Book of Love

Go here for more about

Clarence Darrow.

Clarence Darrow.

Go here for more about

Clarence Darrow's closing argument.

Clarence Darrow's closing argument.

It follows the full text transcript of

Clarence Darrow's closing argument in the case

Illinois versus Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, delivered at

Chicago, Illinois - August 22, 1924.

This is page 2 of 2. Go here for

page 1 of this speech.

page 1 of this speech.

Now, these facts are beyond dispute. He early

developed the tendency to mix with crime, to be

a detective; as a little boy shadowing people on

the street; as a little child going out with his

fantasy of being the head of a band of criminals

and directing them on the street. How did this

grow and develop in him? Let us see. It seems to

me as natural as the day following the night.

Every detective story is a story of a sleuth

getting the best of it; trailing some

unfortunate individual through devious ways

until his victim is finally landed in jail or

stands on the gallows. They all show how smart

the detective is, and where the criminal himself

falls down.

This boy early in his life conceived the idea

that there could be a perfect crime, one that

nobody could ever detect; that there could be

one where the detective did not land his game; a

perfect crime. He had been interested in the

story of Charley Ross, who was kidnapped. He was

interested in these things all his life. He

believed in his childish way that a crime could

be so carefully planned that there would be no

detection, and his idea was to plan and

accomplish a perfect crime. It would involve

kidnapping, and involve murder.

They wanted to commit a perfect crime. There had

been growing in this brain, dwarfed and twisted,

not due to any wickedness of Dickie Loeb, for he

is a child. It grew as he grew; it grew from

those around him; it grew from the lack of the

proper training until it possessed him. He

believed he could beat the police. He believed

he could plan the perfect crime. He had thought

of it and talked of it for years. Had talked of

it as a child; had worked at it as child, and

this sorry act of his, utterly irrational and

motiveless, a plan to commit a perfect crime

which must contain kidnapping, and there must be

ransom, or else it could not perfect, and they

must get the money.

We might as well be honest with ourselves, Your

Honor. Before would tie a noose around the neck

of a boy I would try to call back my mind the

emotions of youth. I would try to remember what

world looked like to me when I was a child. I

would try to remember how strong were these

instinctive, persistent emotions that moved

life. I would try to remember how weak and

inefficient was youth in presence of the

surging, controlling feelings of the child.

But, Your Honor, that is not all there is to

boyhood. Nature is strong and she is pitiless.

She works in her own mysterious way, and we are

her victims. We have not much to do with it

ourselves. Nature takes this job in hand, and we

play our parts. In the words of old Omar

Khayyam, we are only

Impotent pieces in the game He plays

Upon this checkerboard if nights and days,

Hither and thither moves, and checks, and slays,

And one by one back in the closet lays.

What had this boy to do with it? He was not his

own father; he was not his own mother; he was

not his own grandparents. All of this was handed

to him. He did not surround himself with

governesses and wealth. He did not make himself

and yet he is to be compelled to pay.

For God's sake, are we crazy? In the face of

history, of every line of philosophy, against

the teaching of every religionist and seer and

prophet the world has ever given us, we are

still doing what our barbaric, ancestors did

when they came out of the caves and the woods.

Your Honor, I am almost ashamed to talk about

it. I can hardly imagine that we are in the

twentieth century. And yet there are men who

seriously say that for what Nature has done, for

what life has done, for what training has done,

you should hang these boys.

I say this again, without finding fault with his

parents, for whom I have the highest regard, and

.who doubtless did the best they could. They

might have done better if they had not had so

much money. I do not know. Great wealth often

curses all who touch it..

I catch myself many and many a time repeating

phrases of my childhood, and I have not quite

got into my second childhood yet. I have caught

myself doing this while I still could catch

myself. It means nothing. We may have all the

dreams and visions and build all the castles we

wish, but the castles of youth should be

discarded with youth, and when they linger to

the time when boys should think wiser things,

then it indicates a diseased mind. "When I was

young I thought as a child, I spoke as a child,

I understood as a child; but now I have put off

childish things," said the Psalmist twenty

centuries ago. It is when these dreams of

boyhood, these fantasies of youth still linger,

and the growing boy is still a child, a child in

emotion, a child in feeling, a child in

hallucinations that you can say that it is the

dreams and the hallucinations of childhood that

are responsible for his conduct. There is not an

act in all this horrible tragedy that was not

the act of a child, the act of a child wandering

around in the morning of life, moved by the new

feelings of a boy, moved by the uncontrolled

impulses which his teaching was not strong

enough to take care of, moved by the dreams and

the hallucinations which haunt the brain of a

child. I say, Your Honor, that it would be the

height of cruelty, of injustice, of wrong and

barbarism to visit the penalty upon this poor

boy.

This boy needed more of home, more love, more

directing. He needed to have his emotions

awakened. He needed guiding hands along the

serious road that youth must travel. Had these

been given him, he would not be here today. Now,

Your Honor, I want to speak of the other lad,

Babe.

Babe is somewhat older than Dick, and is a boy

of remarkable mind, away beyond his years. He is

a sort of freak in this direction, as in others;

a boy without emotions, a boy obsessed of

philosophy, a boy obsessed of learning, busy

every minute of his life.

He went through school quickly; he went to

college young; he could learn faster than almost

everybody else. His emotional life was lacking,

as every alienist and witness in this case

excepting Dr. Krohn has told you. He was just a

half boy, in intellect, an intellectual machine

going without balance and without a governor,

seeking to find out everything there was in life

intellectually; seeking to solve every

philosophy, but using his intellect only.

Of course his family did not understand him; few

men would. His mother died when he was young; he

had plenty of money, everything was given to him

that he wanted. Both these boys with unlimited

money; both these boys with automobiles; both of

these boys with every luxury around them and in

front of them. They grew up in this environment.

Babe took to philosophy. I call him Babe, not

because I want it to affect Your Honor, but

because everybody else does. He is the youngest

of the family and I suppose that is why he got

his nickname. We will call him a man. Mr. Crowe

thinks it is easier to hang a man than a boy,

and so I will call him a man if I can think of

it.

He grew up in this way. He became enamored of

the philosophy of Nietzsche. Your Honor, I have

read almost everything that Nietzsche ever

wrote. He was a man of a wonderful intellect;

the most original philosopher of the last

century. Nietzsche believed that some time the

superman would be born, that evolution was

working toward the superman. He wrote one book,

Beyond Good and Evil, which was a criticism of

all moral codes as the world understands them; a

treatise holding that the intelligent man is

beyond good and evil, that the laws for good and

the laws for evil do not apply to those who

approach the superman. He wrote on the will to

power. Nathan Leopold is not the only boy who

has read Nietzsche. He may be the only one who

was influenced in the way that he was

influenced.

At seventeen, at sixteen, at eighteen, while

healthy boys were playing baseball or working on

the farm, or doing odd jobs, Babe was reading

Nietzsche, a boy who never should have seen it,

at that early age.

Nietzsche held a contemptuous, scornful attitude

to all those things which the young are taught

as important in life; a fixing of new values

which are not the values by which any normal

child has ever yet been reared. Nietzsche's

attitude is but a philosophical dream,

containing more or less truth, that was not

meant by anyone to be applied to life.

Nietzsche says, "The morality of the master

class is irritating to the taste of the present

day because of its fundamental principle that a

man has obligation only to his equals; that he

may act to all of lower rank and to all that are

foreign, as he pleases."

In other words, man has no obligations; he may

do with all other men and all other boys, and

all society, as he pleases. The superman was a

creation of Nietzsche.

The supermanlike qualities lie not in their

genius, but in their freedom from scruple. They

rightly felt themselves to be above the law.

What they thought was right, not because

sanctioned by any law, beyond themselves, but

because they did it. So the superman will be a

law unto himself What he does will come from the

will and superabundant power within him.

Here is a boy at sixteen or seventeen becoming

obsessed with these doctrines. There isn't any

question about the facts. Their own witnesses

tell it and every one of our witnesses tell it.

It was not a casual bit of philosophy with him;

it was his life. He believed in a superman. He

and Dickie Loeb were the supermen. There might

have been others, but they were two, and two

chums. The ordinary commands of society were not

for him.

Many of us read this philosophy but know that it

has no actual application to life; but not he.

It became a part of his being. It was his

philosophy. He lived it and practiced it; he

thought it applied to him, and he could not have

believed it excepting that it either caused a

diseased mind or was the result of a diseased

mind.

Here is a boy who by day and by night, in season

and out, was talking of the superman, owing no

obligations to anyone; whatever gave him

pleasure he should do, believing it just as

another man might believe a religion or any

philosophical theory.

You remember that I asked Dr. Church about these

religious cases and he said, "Yes, many people

go to the insane asylum on account of them,"

that "they place a literal meaning on parables

and believe them thoroughly"? I asked Dr.

Church, whom again I say I believe to be an

honest man, and an intelligent man, I asked him

whether the same thing might be done or might

come from a philosophical belie£ and he said,

"If one believed it strongly enough."

And I asked him about Nietzsche. He said he knew

something of Nietzsche, something of his

responsibility for the war, for which he perhaps

was not responsible. He said he knew something

about his doctrines. I asked him what became of

him, and he said he was insane for fifteen years

just before the time of his death. His very

doctrine is a species of insanity.

Here is a man, a wise man, perhaps not wise, but

a brilliant, thoughtful man who has made his

impress upon the world. Every student of

philosophy knows him. His own doctrines made him

a maniac. And here is a young boy, in the

adolescent age, harassed by everything that

harasses children, who takes this philosophy and

believes it literally. It is a part of his life.

It is his life. Do you suppose this mad act

could have been done by him in any other way?

What could he have to win from this homicide?

A boy with a beautiful home, with automobiles, a

graduate of college, going to Europe, and then

to study law at Harvard; as brilliant in

intellect as any boy that you could find; a boy

with every prospect that life might hold out to

him; and yet he goes out and commits this weird,

strange, wild, mad act, that he may die on the

gallows or live in a prison cell until he dies

of old age or disease.

He did it, obsessed of an idea, perhaps to some

extent influenced by what has not been developed

publicly in this case-perversions this case were

present in the boy. Both signs of insanity,

both, together with this act, proving a diseased

mind..

Is there any question about what was responsible

for him?

What else could be? A boy in his youth, with

every promise that the world could hold. out

before him, wealth and position and intellect,

yes, genius, scholarship, nothing that he could

not obtain, and he throws it away, and mounts

the gallows or goes into a cell for life. It is

too foolish to talk about. Can Your Honor

imagine a sane brain doing it? Can you imagine

it coming from anything but a diseased mind? Can

you imagine it is any part of normality? And

yet, Your Honor, you are asked to hang a boy of

his age, abnormal, obsessed of dreams and

visions, a philosophy that destroyed his life,

when there is no sort of question in the world

as to what caused his downfall.

I know, Your Honor, that every atom of life in

all this universe is bound up together. I know

that a pebble cannot be thrown into the ocean

without disturbing every drop of water in the

sea. I know that every life is inextricably

mixed and woven with every other life. I know

that every influence, conscious and unconscious,

acts and reacts on every living organism, and

that no one can fix the blame. I know that all

life is a series of infinite chances, which

sometimes result one way and sometimes another.

I have not the infinite wisdom that can fathom

it, neither has any other human brain. But I do

know that if back of it is a power that made it,

that power alone can tell, and if there is no

power then it is an infinite chance which man

cannot solve.

Why should this boy's life be bound up with

Frederick Nietzsche, who died thirty years ago,

insane, in Germany? I don't know. I only know it

is. I know that no man who ever wrote a line

that I read failed to influence me to some

extent. I know that every life I ever touched

influenced me, and I influenced it; and that it

is not given to me to unravel the infinite

causes and say, "This is I, and this is you." I

am responsible for so much; and you are

responsible for so much. I know that in the

infinite universe everything has its place and

that the smallest particle is a part of all.

Tell me that you can visit the wrath of fate and

chance and life and eternity upon a

nineteen-year-old boy! If you could, justice

would be a travesty and mercy a fraud.

There is something else in this case, Your

Honor, that is stronger still. There is a large

element of chance in life. I know I will die. I

don't know when; I don't know how; I don't know

where; and I don't want to know. I know it will

come. I know that it depends on infinite

chances. Did I make myself? And control my fate?

I cannot fix my death unless I commit suicide,

and I cannot do that because the will to live is

too strong; I know it depends on infinite

chances.

Take the rabbit running through the woods; a fox

meets him at a certain fence. If the rabbit had

not started when it did, it would not have met

the fox and would have lived longer. If the fox

had started later or earlier it would not have

met the rabbit and its fate would have been

different.

My death will depend upon chances. It may be by

the taking in of a germ; it may be a pistol; it

may be the decaying of my faculties, and all

that makes life; it may be a cancer; it may be

anyone of an indefinite number of things, and

where I am at a certain time, and whether I take

in that germ, and the condition of my system

when I breathe is an accident which is sealed up

in the book of fate and which no human being can

open.

These boys, neither one of them, could possibly

have committed this act excepting by coming

together. It was not the act for one; it was the

act of two. It was the act of their planning,

their conniving, their believing in each other;

their thinking themselves supermen. Without it

they could not have done it. It would not have

happened. Their parents happened to meet, these

boys happened to meet; some sort of chemical

alchemy operated so that they cared for each

other, and poor Bobby Franks's dead body was

found in the culvert as a result. Neither of

them could have done it alone.

I want to call your attention, Your Honor, to

the two letters in this case which settle this

matter to my mind conclusively; not only the

condition of these boys' minds, but the terrible

fate that overtook them.

Your Honor, I am sorry for poor Bobby Franks,

and I think anybody who knows me knows that I am

not saying it simply to talk. I am sorry for the

bereaved father and the bereaved mother, and I

would like to know what they would do with these

poor unfortunate lads who are here in this court

today. I know something of them, of their lives,

their charity, of their ideas, and nobody here

sympathizes with them

more than I.

On the twenty-first day of May, poor Bobby

Franks, stripped naked, was left in a culvert

down near the Indiana line. I know it came

through the mad act of mad boys. Mr. Savage told

us that Franks, if had lived, would have been a

great man and have accomplished much. I want to

leave this thought with Your Honor now. I do not

know what Bobby Franks would have been had he

grown to be a man. I do not know the laws that

control one's growth. Sometimes, Your Honor, a

boy of great promise is cut off in his early

youth. Sometimes he dies and is placed in a

culvert. Sometimes a boy of great promise stands

on a trap door and is hanged by the neck until

dead. Sometimes he dies of diphtheria. Death

somehow pays no attention to age, sex,

prospects, wealth or intellect.

And I want to say this, that the death of poor

little Bobby Franks should not be in vain. Would

it mean anything if on account of that death

these two boys were taken out and a rope tied

around their necks' and they died felons? Would

that show that Bobby Franks had a purpose in his

life and a purpose in his death? No, Your Honor,

the unfortunate and tragic death of this weak

young lad should mean something. I should mean

an appeal to the fathers and the mothers, an

appeal to the, teachers, to the religious

guides, to society at large. It should mean an

appeal to all of them to appraise children, to

understand the emotions that control them, to

understand the ideas that possess them, to teach

them to avoid the pitfalls of life.

I have discussed somewhat in detail these two

boys separately. The coming together was the

means of their undoing. Your Honor is familiar

with the facts in reference to their

association. They had a weird, almost impossible

relationship. Leopold, with his obsession of the

superman, had repeatedly said that Loeb was his

idea of the superman. He had the attitude toward

him that one has to his most devoted friend, or

that a man has to a lover. Without the

combination of these two nothing of this sort

probably could have happened. It is not

necessary for us, Your Honor, to rely upon words

to prove the condition of the boys' minds, and

to prove the effect of this strange and fatal

relationship between these two boys.

It is mostly told in a letter which the state

itself introduced in case. Not the whole story,

but enough of it is shown, so that no

intelligent, thoughtful person could fail to

realize what was the relationship between them

and how they had played upon each other to

effect their downfall and their ruin. I want to

read this letter once more, a letter which was

introduced by the state, a letter dated October

9, a month and three days before their trip to

Ann Arbor, and I want the court to say in his

own mind whether this letter was anything but

the products of a diseased mind, and if it does

not show a relationship that was responsible for

this terrible homicide. This was written by

Leopold to Loeb. They lived close together, only

a few blocks from each other; saw each other

every day, but Leopold wrote him this letter:

October 9,1923.

Dear Dick:

In view of our former relations, I take it for

granted that its [sic] unnecessary to make any

excuse for writing you at this time, and still I

am going to state my reasons for so doing, as

this may turn out to be a long letter, and I

don't want to cause you the inconvenience of

reading it all to find out what it contains if

you are not interested in the subjects dealt

with.

First, I am enclosing the document which I

mentioned to you today, and which I will explain

later. Second, I am going to tell you of a new

fact which has come up since our discussion. And

third, I am going to put in writing what my

attitude toward our present relations, with a

view of avoiding future possible

misunderstandings, and in the hope (though I

think it rather vain) that possibly we may have

misunderstood each other, and can yet clear this

matter up.

Now, as to the first, I wanted you this

afternoon, and still want you, to feel that we

are on an equal footing legally, and therefore,

I purposely committed the same tort of which you

were guilty, the only difference being that in

your case the facts would be harder to prove

than in mine, should I deny them. The enclosed

document should secure you against changing my

mind in admitting the facts, if the matter

should come up, as it would prove to any court

that they were true.

As to the second. On your suggestion I

immediately phoned Dick Rubel, and speaking from

a paper prepared beforehand (to be sure of the

exact wording) said: "Dick, when we were

together yesterday, did I tell you that Dick

(Loeb) had told me the things which I then told

you, or that it was merely my opinion that I

believed them to be so?"

I asked this twice to be sure he understood, and

on the same answer both times (which I took down

as he spoke) felt that he did understand.

He replied: "No, you did not tell me that Dick

told you these things, but said that they were

in your opinion true."

He further denied telling you subsequently that

I had said that they were gleaned from

conversation with you, and I then told him that

he was quite right, that you never had told me.

I further told him that this was merely your

suggestion of how to settle a question of fact

that he was in no way implicated, and that

neither of us would be angry with him at his

reply. (I imply your assent to this.)

This of course proves that you were mistaken

this afternoon in the question of my having

actually and technically broken confidence, and

voids my apology, which I made contingent on

proof of this matter.

Now, as to the third, last, and most important

question. When you came to my home this

afternoon I expected either to break friendship

with you or attempt to kill you unless you told

me why you acted as you did yesterday.

You did, however, tell me, and hence the

question shifted to the fact that I would act as

before if you persisted in thinking me

treacherous, either in act (which you waived if

Dick's opinion went with mine) or in intention.

Now, I apprehend, though here I am not quite

sure, that you said that you did not think me

treacherous in intent, nor ever have, but that

you considered me in the wrong and expected such

statement from me. This statement I

unconditionally refused to make until such time

as I may become convinced of its truth.

However, the question of our relation I think

must be in your hands (unless the above

conceptions are mistaken), inasmuch as you have

satisfied first one and then the other

requirement, upon which I agreed to refrain from

attempting to kill you or refusing to continue

our friendship. Hence I have no reason not to

continue to be on friendly terms with you, and

would under ordinary conditions continue as

before.

The only question, then, is with you. You demand

me to perform an act, namely, state that I acted

wrongly. This I refuse. Now it is up to you to

inflict the penalty for this refusal at your

discretion, to break friendship, inflict

physical punishment, or anything else you like,

or on the other hand to continue as before.

The decision, therefore, must rest with you.

This is all of my opinion on the right and wrong

of the matter.

Now comes a practical question. I think that I

would ordinarily be expected to, and in fact do

expect to continue my attitude toward you, as

before, until I learn either by direct words or

by conduct on your part which way your decision

has been formed. This I shall do.

Now a word of advice. I do not wish to influence

your decision either way, but I do want to warn

you that in case you deem it advisable to

discontinue our friendship, that in both our

interests extreme care must be had. The motif of

"A falling out of-" would be sure to be popular,

which is patently undesirable and forms an

irksome but unavoidable bond between us.

Therefore, it is, in my humble opinion,

expedient, though our breech need be no less

real in fact, yet to observe the

conventionalities, such as salutation on the

street and a general appearance of at least not

unfriendly relations on all occasions when we

may be thrown together in public.

Now, Dick, I am going to make a request to which

I have perhaps no right, and yet which I dare to

make also for "Auld Lang Syne." Will you, if not

too inconvenient, let me know your answer

(before I leave tomorrow) on the last count?

This, to which I have no right, would greatly

help my peace of mind in the next few days when

it is most necessary to me. You can if you will

merely call up my home before 12 noon and leave

a message saying, "Dick says yes," if you wish

our relations to continue as before, and "Dick

says no," if not.

It is unnecessary to add that your decision will

of course have no effect on my keeping to myself

our confidences of the past, and that I regret

the whole affair more than I can say.

Hoping not to have caused you too much trouble

in reading this, I am (for the present), as ever

"BABE"

Now, I undertake to say that under any

interpretation of this taking into account all

the things Your Honor knows, that have not been

made public, or leaving them out, nobody can

interpret that letter excepting on the theory of

a diseased mind, and with it goes this strange

document which was referred to in the letter:

I, Nathan F. Leopold Jr. being under no duress

or compulsion, do hereby affirm and declare that

on this, the ninth day of October, 1923, I for

reasons of my own locked the door of the room in

which I was with one Richard A. Loeb, with the

intent of blocking his only feasible mode of

egress, and that I further indicated my

intention of applying physical force upon the

person of the said Richard A. Loeb if necessary

to carry out my design, to wit, to block his

only feasible mode of egress.

There is nothing in this case, whether heard

alone by the court or heard in public, that can

explain these documents, on the theory that the

defendants were normal human beings....

But I am going to add a little more in an effort

to explain my system of the Nietzschean

philosophy with regard to you. It may not have

occurred to you why a mere mistake in judgment

on your part should be treated as a crime when

on the part of another it should not be so

considered? Here are the reasons. In formulating

a superman he is, on account of certain superior

qualities inherent in him, exempted from the

ordinary laws which govern ordinary men. He is

not liable for anything he may do, whereas

others would be, except for the one crime that

it is possible for him to commit, to make a

mistake.

Now obviously any code which conferred upon an

individual or upon a group extraordinary

privileges without also putting on him

extraordinary responsibility, would be unfair

and bad. Therefore, the superman is held to have

committed a crime every time he errs in

judgment, a mistake excusable in others. But you

may say that you have previously made mistakes

which did not treat as crimes. This is true. To

cite an example, the other night you expressed

the opinion, and insisted, that Marcus Aurelius

Antonius was practically the founder of

Stoicism. In so doing you committed a crime. But

it was a slight crime, and I chose to forgive

it. I have, and had before that, forgiven the

crime which you committed in committing the

error in judgment which caused the whole train

of events. I did not and do not wish to charge

you with crime, but I feel justified in using

any of the consequences of your crime for which

you are held responsible, to my advantage. This

and only this I did, so you see how careful you

must be.

Is that the letter of a normal eighteen-year-old

boy, or is it the letter of a diseased brain? Is

that the letter of boys acting as boys should,

and thinking as boys should, or is it the letter

of one whose philosophy has taken possession of

him, who understands that what the world calls a

crime is something that the superman may do, who

believes that the only crime the superman can

commit is to make a mistake? He believed it. He

was immature. It possessed him. It was manifest

in the strange compact that the court already

knows about between these two boys, by which

each was to yield something and each was to give

something. Out of that compact and out of these

diseased minds grew this terrible crime.

I submit the facts do not rest on the evidence

of these boys alone. It is proven by the

writings; it is proven by every act. It is

proven by their companions, and there can be no

question about it.

We brought into this courtroom a number of their

boyfriends, whom they had known day by day, who

had associated with them in the club-house, were

their constant companions, and they tell the

same stories. They tell the story that neither

of these two boys was responsible for his

conduct.

Maremont, whom the state first called, one of

the oldest of the boys, said that Leopold had

never had any judgment of any sort. They talked

about the superman. Leopold argued his

philosophy. It was a religion with him. But as

to judgment of things in life he had none. He

was developed intellectually, wanting

emotionally, developed in those things which a

boy does not need and should not have at his

age, but absolutely void of the healthy

feelings, of the healthy instincts of practical

life that are necessary to the child.

We called not less than ten or twelve of their

companions and all of them testified the same:

Dickie Loeb was not allowed by his companions

the privileges of his class because of his

childishness and his lack of judgment.

As to the standing of these boys amongst their

fellows, that they were irresponsible, that they

had no judgment, that they were childish, that

their acts were strange, that their beliefs were

impossible for boys, is beyond question in this

case.

And what did they do on the other side?

It was given out that they had a vast army of

witnesses. They called. three. A professor who

talked with Leopold only upon his law studies,

and two others who admitted all that we said, on

cross-examination, and the rest were dismissed.

So it leaves all of this beyond dispute and

admitted in this case.

Now both sides have called alienists and I will

refer to that for a few, moments. I shall only

take a little time with the alienists.

The facts here are plain; when these boys had

made the confession on Sunday afternoon before

their counsel or their friends had any chance to

see them, Mr. Crowe sent out for four men. He

sent out for Dr. Patrick, who is an alienist;

Dr. Church, who is an alienist; Dr. Krohn, who

is a witness, a testifier; and Dr. Singer, who

is pretty good, I would not criticize him but

would not class him with Patrick and with

Church. I have said to Your Honor that in my

opinion he sent for the two ablest men in

Chicago as far as the public knows them, Dr.

Church and Dr. Patrick. You heard Dr. Church's

testimony. Dr. Church is an honest man though an

alienist. Under cross-examination he admitted

every position which I took. He admitted the

failure of emotional life in these boys; he

admitted its importance; he admitted the

importance of beliefs strongly held in human

conduct; he said himself that if he could get at

all the facts he would understand what was back

of this strange murder. Every single position

that we have claimed in this case Dr. Church

admitted.

Dr. Singer did the same. The only difference

between them was this it took but one question

to get Dr. Church to admit it, and it took ten

to a dozen to get Dr. Singer. He objected and

hedged and ran and quibbled. There could be no

mistake about it, and Your Honor heard it in

this courtroom. He sought every way he could to

avoid the truth, and when it came to the point

that he could not dodge any longer, he

admitted every proposition just exactly the same

as Dr. Church admitted them: the value of

emotional life; its effect on conduct; that it

was the ruling thing in conduct, as every person

knows who is familiar with psychology and who is

familiar with the human system.

Could there be any doubt, Your Honor, but what

both those witnesses, Church and Singer, or any

doubt but what Patrick would have testified for

us? Now what did they do in their examination?

What kind of a chance did these alienists have?

It is perfectly obvious that they had none.

Church, Patrick, Krohn went into a room with

these two boys who had been in the possession of

the state's attorney's office for sixty hours;

they were surrounded by policemen, were

surrounded by guards and detectives and state's

attorneys; twelve or fifteen of them, and here

they told their story. Of course this audience

had a friendly attitude toward them. I know my

friend Judge Crowe had a friendly attitude

because I saw divers, various and sundry

pictures of Prosecutor Crowe taken with these

boys.

When I first saw them I believed it showed

friendship for the boys, but now I am inclined

to think that he had them taken just as a lawyer

who goes up in the country fishing has his

picture taken with his catch. The boys had been

led doubtless to believe that these people were

friends. They were taken there, in the presence

of all this crowd. What was done? The boys told

their story, and that was all. Of course, Krohn

remembered a lot that did not take place, and we

would expect that of him; and he forgot much

that did take place and we would expect that of

him, too. So far as the honest witnesses were

concerned, they said that not a word was spoken

excepting a little conversation upon birds and

the relation of the story that they had already

given to the state's attorney; and from that,

and nothing else, both Patrick and Church said

they showed no reaction as ordinary persons

should show it, and intimated clearly that the

commission of the crime itself would put them on

inquiry as to whether these boys were mentally

right; both admitted that the conditions

surrounding them made the right kind of

examination impossible; both admitted that they

needed a better chance to form a reliable

opinion.

The most they said was that at this time they

saw no evidence of Insanity.

Now, Your Honor, no experts, and no alienists

with any chance to examine, have testified that

these boys were normal.

Singer did a thing more marvelous still. He

never saw these boys until he came into this

court, excepting when they were brought down in

violation of their constitutional rights to the

office of judge Crowe, after they had been

turned over to the jailer, and there various

questions were asked them, and to all of these

the boys replied that they respectfully refused

to answer on advice of counsel. And yet that was

enough for Singer.

Your Honor, if these boys had gone to the office

of anyone of the eminent gentlemen, had been

taken by their parents or gone by themselves,

and the doctors had seriously tried to find out

whether there was anything wrong about their

minds, how would they have done it? They would

have taken them patiently and carefully. They

would have sough to get their confidence. They

would have listened to their story. The would

have listened to it in the attitude of a father

listening to his child. You know it. Every

doctor knows it. In no other way could they find

their mental condition. And the men who are

honest with this question

have admitted it.;

And yet Dr. Krohn will testify that they had the

best chance in the world, when his own

associates, sitting where they were, said they

did not.

Your Honor, nobody's life or liberty or property

should be taken from them upon an examination

like that. It was not an examination. It was

simply an effort to get witnesses, regardless of

facts, who might a some time come into court and

give their testimony, to take these boys' lives.

Now, I imagine that in closing this case judge

Crowe will say that our witnesses mainly came

from the East. That is true. And he is

responsible for it. I am not blaming him, but he

is responsible for it. There are other alienists

in Chicago, and the evidence shows that we had

the boys examined by numerous ones in Chicago.

We wanted to get the best. Did we get them?

Your Honor knows that the place where a man

lives does not affect his truthfulness or his

ability. We brought the man who stands probably

above all of them, and who certainly is far

superior to anybody called upon the other side.

First of all, we called Dr. William A. White.

And who is he? For many years he has been

superintendent of the Government Hospital for

the Insane in Washington; a man who has written

more books, delivered more lectures, and had

more honors, and knows this subject better than

all of their alienists put together; a man who

plainly came here not for money, and who

receives for his testimony the same per diem as

is paid by the other side; a man who knows his

subject, and whose ability and truthfulness must

have impressed this court. It will not do, Your

Honor, to say that because Dr. White is not a

resident of Chicago that he lies. No man stands

higher in the United States, no man is better

known than Dr, White, his learning and

intelligence was obvious from his evidence in

this case.

Who else did we get? Do I need to say anything

about Dr. Healy? Is there any question about his

integrity? A man who seldom goes into court

except upon the order of the court.

Your Honor was connected with the Municipal

Court. You know that Dr. Healy was the first man

who operated with the courts in the city of

Chicago to give aid to the unfortunate youths

whose minds were afflicted and who were the

victims of the law. His books are known wherever

men study boys. His reputation is known all over

the United States and in Europe. Compare him and

his reputation with Dr. Krohn. Compare it with

any other witness that the state called in this

case.

Dr. Glueck, who was for years the alienist at

Sing Sing, and connected with the penal

institutions in the state of New York; a man of

eminent attainments and ripe scholarship. No one

is his superior. And Dr. Hulbert, a young man

who spent nineteen days in the examination of

these boys, together with Dr. Bowen, an eminent

doctor in his line from Boston. These two

physicians spent all this time getting every

detail of these boys' lives, and structures;

each one of these alienists took all the time

they needed for a thorough examination, without

the presence of lawyers, detectives, and

policemen. Each one of these psychiatrists tells

this court the story, the sad, pitiful story, of

the unfortunate minds of these two young lads.

I submit, Your Honor, that there can be no

question about the relative value of these two

sets of alienists; there can be no question of

their means of understanding; there can be no

question but that "White, Glueck, Hulbert, and

Healy knew what they were talking about, for

they had every chance to find out. They are

either lying to this court, or their opinions

good.

On the other hand, not one single man called by

the state had any chance to know. He was called

in to see these boys, the same as the state

would call a hangman: "Here are the boys;

officer, do your duty." And that is all there

was of it.

Now, Your Honor, I shall pass that subject. I

think all of the facts of this extraordinary

case, all of the testimony of the alienists, all

that Your Honor has seen and heard, all their

friends and acquaintances who have come here to

enlighten this court, I think all of it shows

that this terrible act was the act of immature

and diseased brains, the act of children. Nobody

can explain it in any other way. No one can

imagine it in any other way. It is not possible

that it could have happened in any other way.

And I submit, Your Honor, that by every law of

humanity, by every law of justice, by every

feeling of righteousness, by every instinct of

pity, mercy, and charity, Your Honor should say

that because of the condition of these boys'

minds, it would be monstrous to visit upon them

the vengeance that is asked by the state.

I want to discuss now another thing which this

court must consider and which to my mind is

absolutely conclusive in this case. That is, the

age of these boys.

I shall discuss it more in detail than I have

discussed it before, and I submit, Your Honor,

that it is not possible for any court to hang

thesis two boys if he pays any attention

whatever to the modern attitude toward the

young, if he pays any attention whatever to the

precedents in this county, if he pays any

attention to the humane instincts which move

ordinary men.

I have a list of executions in Cook County

beginning in 1840, which I presume covers the

first one, because I asked to have it go to the

beginning. Ninety poor unfortunate men have

given up their lives to stop murder in Chicago.

Ninety men have been hanged by the neck until

dead, because of the ancient superstition that

in some way hanging one man keeps another from

committing a crime. The ancient superstition, I

say, because I defy the state to point to a

criminologist, a scientist, student, who has

ever said it. Still we go on, as if human

conduct was not influenced and controlled by

natural laws the same as all the rest of the

universe is the subject of law. We treat crime

as if it had no cause. We go on saying, "Hang

the unfortunates, and it will end." Was there

ever a murder without a cause? Was there ever a

crime without a cause? And yet all punishment

proceeds upon the theory that there is no cause;

and the only way to treat crime is to intimidate

every one into goodness and obedience to law. We

lawyers are a long way behind.

Crime has its cause. Perhaps all crimes do not

have the same cause. Perhaps all crimes do not

have the same cause but they all have some

cause. And people today are seeking to find out

the cause. We lawyers never try to find out.

Scientists are studying it; criminologists are

investigating it; but we lawyers go on and on

and on, punishing and hanging and thinking that

by general terror we can stamp out crime.

It never occurs to the lawyer that crime has a

cause as certainly as disease, and that the way

to rationally treat any abnormal condition is to

remove the cause. If a doctor were called on to

treat typhoid fever he would probably try to

find out what kind of milk or water the patient

drank, and perhaps clean out the well so that no

one else could get typhoid from the same source.

But if a lawyer was called on to treat a typhoid

patient, he would give him thirty days in jail,

and then he would think that nobody else would

ever dare to take it. If the patient got well in

fifteen days, he would be kept until his time

was up; if the disease was worse at the end of

thirty days, the patient would be released

because his time was out.

As a rule, lawyers are not scientists. They have

learned the doctrine of hate and fear, and they

think that there is only one way to make men

good, and that is to put them in such terror

that they do not dare to be bad. They act

unmindful of history, and science, and all the

experience of the past.

Still, we are making some progress. Courts give

attention to some things that they did not give

attention to before.

Once in England they hanged children seven years

of age; not necessarily hanged them, because

hanging was never meant for punishment; it was

meant for an exhibition. If somebody committed a

crime, he would be hanged by the head or the

heels, it didn't matter much which, at the four

crossroads, so that everybody could look at him

until his bones were bare, and so that people

would be good because they had seen the gruesome

result of crime and hate.

Hanging was not necessarily meant for

punishment. The culprit might be killed in any

other way, and then hanged. Hanging was an

exhibition. They were hanged on the highest

hill, and hanged at the crossways, and hanged in

public places, so that all men could see. If

there is any virtue in hanging, that was the

logical way, because you cannot awe men into

goodness unless they know about the hanging. We

have not grown better than the ancients. We have

grown more squeamish; we do not like to look at

it, that is all. They hanged them at seven

years; they hanged them again at eleven and

fourteen.

We have raised the age of hanging. We have

raised it by the humanity of courts, by the

understanding of courts, by the progress in

science which at last is reaching the law; and

in ninety men hanged in Illinois from its

beginning, not one single person under

twenty-three was ever hanged upon a plea of

guilty, not one. If Your Honor should do this,

you would violate every precedent that had been

set in Illinois for almost a century. There can

be no excuse for it, and no justification for

it, because this is the policy of the law which

is rooted in the feelings of humanity, which are

deep in every human being that thinks and feels.

There have been two or three cases where juries

have convicted boys younger than this, and where

courts on convictions have refused to set aside

the sentence because a jury had found it.

Your Honor, what excuse could you possibly have

for putting these boys to death? You would have

to turn your back on every precedent of the

past. You would have to turn your back on the

progress of the world. You would have to ignore

all human sentiment and feeling, of which I know

the court has his full share. You would have to

do all this if you would hang boys of eighteen

and nineteen years of age who have come into

this court and thrown themselves upon your

mercy.

Your Honor, I must hasten along, for I will

close tonight. I know I should have closed

before. Still there seems so much that I would

like to say. I do not know whether Your Honor,

humane and considerate as I believe you to be,

would have disturbed a jury's verdict in his

case, but I know that no judge in Cook County

ever himself upon a plea of guilty passed

judgment of death in a case below the age of

twenty-three, and only one at the age of

twenty-three was ever hanged on a plea of

guilty.

Your Honor, if in this court a boy of eighteen

and a boy of nineteen should be hanged on a plea

of guilty, in violation of every precedent of

the past, in violation of the policy of the law

to take care of the young, in violation of all

the progress that has been made and of the

humanity that has been shown in the care of the

young; in violation of the law that places boys

in reformatories instead of prisons, if Your

Honor in violation of all that and in the face

of all the past should stand here in Chicago

alone to hang a boy on a plea of guilty, then we

are turning our' faces backward, toward the

barbarism which once possessed the world. If

Your Honor can hang a boy at eighteen, some

other judge can hang him at seventeen, or

sixteen, or fourteen. Someday, if there is any

such thing as progress in the world, if there is

any spirit of humanity that is working in the

hearts of men, someday men would look back upon

this as a barbarous age which deliberately set

itself in the way of progress, humanity, and

sympathy, and committed an unforgivable act.

I do not know how much salvage there is in these

two boys, hate to say it in their presence, but

what is there to look forward to? I do not know

but what Your Honor would be merciful if you

tied a rope around their necks and let them die;

merciful to them, but not merciful to

civilization, and not merciful to those who

would be left behind. To spend the balance of

their days in prison is mighty little to look

forward to, if anything. Is it anything? They

may have the hope that as the years roll around

they might be released. I do not know. I will be

honest with this court as I have tried to be

from the beginning. I know that these boys are

not fit to be at large. I believe they will not

be until they pass through the next stage of

life, at forty-five or fifty. Whether they will

be then, I cannot tell. I am sure of this; that

I will not be here to help them. So far as I am

concerned, it is over.

I would not tell this court that I do not hope

that some time, when life and age has changed

their bodies, as it does, and has changed their

emotions, as it does, that they may once more

return to life. I would be the last person on

earth to close the door of hope to any human

being that lives, and least of all to my

clients. But what have they to look forward to?

Nothing. And I think here of the stanzas of

Housman:

Now hollow fires burn out to black,

And lights are fluttering low:

Square your shoulders, lift your pack

And leave your friends and go.

O never fear, lads, naught's to dread,

Look not left nor right:

In all the endless road you tread

There's nothing but the night.

I care not, Your Honor, whether the march begins

at the gallows or when the gates of Joliet close

upon them, there is nothing but the night, and

that is little for any human being to expect.

But there are others to be considered. Here are

these two families, who have led honest lives,

who will bear the name that they bear, and

future generations must carry it on. Here is

Leopold's father, and this boy was the pride of

his life. He watched him, he cared for him, he

worked for him; the boy was brilliant and

accomplished, he educated him, and he thought

that fame and position awaited him, as it should

have awaited. It is a hard thing for a father to

see his life's hopes crumble into dust.

Should he be considered? Should his brothers be

considered? Will it do society any good or make

your life safer, or any human being's life

safer, if it should be handed down from

generation to generation, that this boy, their

kin, died upon the scaffold?

And Loeb's, the same. Here is the faithful uncle

and brother, who have watched here day by day,

while Dickie's father and his mother are too ill

to stand this terrific strain, and shall be

waiting for a message which means more to them

than it can mean to you or me. Shall these be

taken into account in this general bereavement?

Now, I must say a word more and then I will

leave this with you where I should have left it

long ago. None of us are unmindful of the

public; courts are not, and juries are not. We

placed our fate in the hands of a trained court,

thinking that he would be more mindful and

considerate than a jury. I cannot say how people

feel. I have stood here for three months as one

might stand at the ocean trying to sweep back

the tide. I hope the seas are subsiding and the

wind is falling, and I believe they are, but I

wish to make no false pretense to this court.

The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to

hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do

not think will applaud. The cruel and the

thoughtless will approve. It will be easy today;

but in Chicago, and reaching out over the length

and breadth of the land, more and more fathers

and mothers, the humane, the kind, and the

hopeful, who are gaining an understanding and

asking questions not only about these poor boys

but about their own, these will join in no

acclaim at the death of my clients. But, Your

Honor, what they shall ask may not count. I know

the easy way. I know Your Honor stands between

the future and the past. I know the future is

with me, and what I stand for here; not merely

for the lives of these two unfortunate lads, but

for all boys and all girls; for all of the

young, and as far as possible, for all of the

old. I am pleading for life, understanding,

charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that

considers all. I am pleading that we overcome

cruelty with kindness and hatred with love. I

know the future is on my side. Your Honor stands

between the past and the future. You may hang

these boys; you may hang them, by the neck until

they are dead. But in doing it you will turn

your face toward the past. In doing it you are

making it harder for every other boy who in

ignorance and darkness must grope his way

through the mazes which only childhood knows. In

doing it you will make it harder for unborn

children. You may save them and make it easier

for every child that some time may stand where

these boys stand. You will make it easier for

every human being with an aspiration and a

vision and a hope and a fate. I am pleading for

the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred

and cruelty will not control the hearts of men.

When we can learn by, reason and judgment and

understanding and faith that all life is worth

saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute

of man.

I feel that I should apologize for the length of

time I have taken. This case may not be as

important as I think it is, and I am sure I do

not need to tell this court, or to tell my

friends, that I would fight just as hard for the

poor as for the rich. If I should succeed in

saving these boys' lives and do nothing for the

progress of the law, I should feel sad, indeed.

If I can succeed, my greatest reward and my

greatest hope will be that I have done something

for the tens of thousands of other boys, or the

countless unfortunates who must tread the same

road in blind childhood that these poor boys

have trod, that I have done something to help

human understanding, to temper justice with

mercy, to overcome hate with love.

I was reading last night of the aspiration of

the old Persian poet, Omar Khayyam. It appealed

to me as the highest that can vision. I wish it

was in my heart, and I wish it was in the hearts

of all:

So I be written in the Book of Love,

Do not care about that Book above.

Erase my name or write it as you will,

So I be written in the Book of Love.

This is page 2 of

2. Go here for

page 1 of this speech.

page 1 of this speech.

More History

|

|