|

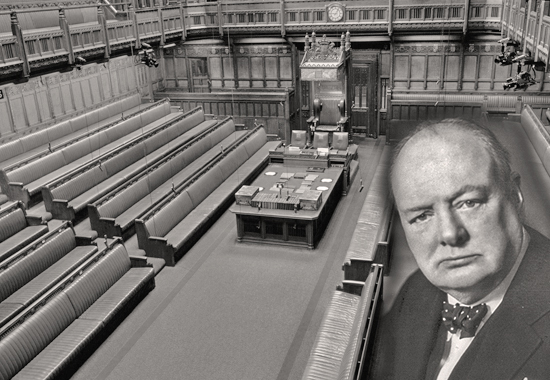

WINSTON CHURCHILL SPEAKS TO THE HOUSE OF

COMMONS, LONDON, UK

British History 1940

The Few

|

Almost a year has

passed since the war began, and it is natural |

for us, I think,

to pause on our journey at this milestone and

survey the dark, wide field. It is also useful

to compare the first year of this second war

against German aggression with its forerunner a

quarter of a century ago. Although this war is

in fact only a continuation of the last, very

great differences in its character are apparent.

In the last war millions of men fought by

hurling enormous masses of steel at one another.

"Men and shells" was the cry, and prodigious

slaughter was the consequence.

In this war nothing of this kind has yet

appeared. It is a conflict of strategy, of

organization, of technical apparatus, of

science, mechanics, and morale. The British

casualties in the first 12 months of the Great

War amounted to 365,000. In this war, I am

thankful to say, British killed, wounded,

prisoners, and missing, including civilians, do

not exceed 92,000, and of these a large

proportion are alive as prisoners of war.

Looking more widely around, one may say that

throughout all Europe for one man killed or

wounded in the first year perhaps five were

killed or wounded in 1914-15.

The slaughter is only a small fraction, but the

consequences to the belligerents have been even

more deadly. We have seen great countries with

powerful armies dashed out of coherent existence

in a few weeks. We have seen the French Republic

and the renowned French Army beaten into

complete and total submission with less than the

casualties which they suffered in any one of

half a dozen of the battles of 1914-18.

The entire body - it might almost seem at times

the soul - of France has succumbed to physical

effects incomparably less terrible than those

which were sustained with fortitude and

undaunted will power 25 years ago. Although up

to the present the loss of life has been

mercifully diminished, the decisions reached in

the course of the struggle are even more

profound upon the fate of nations than anything

that has ever happened since barbaric times.

Moves are made upon the scientific and strategic

boards, advantages are gained by mechanical

means, as a result of which scores of millions

of men become incapable of further resistance,

or judge themselves incapable of further

resistance, and a fearful game of chess proceeds

from check to mate by which the unhappy players

seem to be inexorably bound.

There is another more obvious difference from

1914. The whole of the warring nations are

engaged, not only soldiers, but the entire

population, men, women, and children. The fronts

are everywhere. The trenches are dug in the

towns and streets. Every village is fortified.

Every road is barred. The front line runs

through the factories. The workmen are soldiers

with different weapons but the same courage.

These are great and distinctive changes from

what many of us saw in the struggle of a quarter

of a century ago.

There seems to be every reason to believe that

this new kind of war is well suited to the

genius and the resources of the British nation

and the British Empire and that, once we get

properly equipped and properly started, a war of

this kind will be more favorable to us than the

somber mass slaughters of the Somme and

Passchendaele. If it is a case of the whole

nation fighting and suffering together, that

ought to suit us, because we are the most united

of all the nations, because we entered the war

upon the national will and with our eyes open,

and because we have been nurtured in freedom and

individual responsibility and are the products,

not of totalitarian uniformity but of tolerance

and variety.

If all these qualities are turned, as they are

being turned, to the arts of war, we may be able

to show the enemy quite a lot of things that

they have not thought of yet. Since the Germans

drove the Jews out and lowered their technical

standards, our science is definitely ahead of

theirs. Our geographical position, the command

of the sea, and the friendship of the United

States enable us to draw resources from the

whole world and to manufacture weapons of war of

every kind, but especially of the superfine

kinds, on a scale hitherto practiced only by

Nazi Germany.

Hitler is now sprawled over Europe. Our

offensive springs are being slowly compressed,

and we must resolutely and methodically prepare

ourselves for the campaigns of 1941 and 1942.

Two or three years are not a long time, even in

our short, precarious lives. They are nothing in

the history of the nation, and when we are doing

the finest thing in the world, and have the

honor to be the sole champion of the liberties

of all Europe, we must not grudge these years of

weary as we toil and struggle through them. It

does not follow that our energies in future

years will be exclusively confined to defending

ourselves and our possessions. Many

opportunities may lie open to amphibious power,

and we must be ready to take advantage of them.

One of the ways to bring this war to a speedy

end is to convince the enemy, not by words, but

by deeds, that we have both the will and the

means, not only to go on indefinitely but to

strike heavy and unexpected blows. The road to

victory may not be so long as we expect. But we

have no right to count upon this. Be it long or

short, rough or smooth, we mean to reach our

journey's end.

It is our intention to maintain and enforce a

strict blockade not only of Germany but of

Italy, France, and all the other countries that

have fallen into the German power. I read in the

papers that Herr Hitler has also proclaimed a

strict blockade of the British Islands. No one

can complain of that. I remember the Kaiser

doing it in the last war. What indeed would be a

matter of general complaint would be if we were

to prolong the agony of all Europe by allowing

food to come in to nourish the Nazis and aid

their war effort, or to allow food to go in to

the subjugated peoples, which certainly would be

pillaged off them by their Nazi conquerors.

There have been many proposals, founded on the

highest motives, that food should be allowed to

pass the blockade for the relief of these

populations. I regret that we must refuse these

requests. The Nazis declare that they have

created a new unified economy in Europe. They

have repeatedly stated that they possess ample

reserves of food and that they can feed their

captive peoples.

In a German broadcast of 27th June it was said

that while Mr. Hoover's plan for relieving

France, Belgium, and Holland deserved

commendation, the German forces had already

taken the necessary steps. We know that in

Norway when the German troops went in, there

were food supplies to last for a year. We know

that Poland, though not a rich country, usually

produces sufficient food for her people.

Moreover, the other countries which Herr Hitler

has invaded all held considerable stocks when

the Germans entered and are themselves, in many

cases, very substantial food producers. If all

this food is not available now, it can only be

because it has been removed to feed the people

of Germany and to give them increased rations -

for a change - during the last few months.

At this season of the year and for some months

to come, there is the least chance of scarcity

as the harvest has just been gathered in. The

only agencies which can create famine in any

part of Europe now and during the coming winter,

will be German exactions or German failure to

distribute the supplies which they command.

There is another aspect. Many of the most

valuable foods are essential to the manufacture

of vital war material. Fats are used to make

explosives. Potatoes make the alcohol for motor

spirit. The plastic materials now so largely

used in the construction of aircraft are made of

milk. If the Germans use these commodities to

help them to bomb our women and children, rather

than to feed the populations who produce them,

we may be sure that imported foods would go the

same way, directly or indirectly, or be employed

to relieve the enemy of the responsibilities he

has so wantonly assumed.

Let Hitler bear his responsibilities to the full

and let the peoples of Europe who groan beneath

his yoke aid in every way the coming of the day

when that yoke will be broken. Meanwhile, we can

and we will arrange in advance for the speedy

entry of food into any part of the enslaved

area, when this part has been wholly cleared of

German forces, and has genuinely regained its

freedom. We shall do our best to encourage the

building up of reserves of food all over the

world, so that there will always be held up

before the eyes of the peoples of Europe,

including - I say deliberately - the German and

Austrian peoples, the certainty that the

shattering of the Nazi power will bring to them

all immediate food, freedom and peace.

Rather more than a quarter of a year has passed

since the new Government came into power in this

country. What a cataract of disaster has poured

out upon us since then. The trustful Dutch

overwhelmed; their beloved and respected

Sovereign driven into exile; the peaceful city

of Rotterdam the scene of a massacre as hideous

and brutal as anything in the Thirty Years' War.

Belgium invaded and beaten down; our own fine

Expeditionary Force, which King Leopold called

to his rescue, cut off and almost captured,

escaping as it seemed only by a miracle and with

the loss of all its equipment; our Ally, France,

out; Italy in against us; all France in the

power of the enemy, all its arsenals and vast

masses of military material converted or

convertible to the enemy's use; a puppet

Government set up at Vichy which may at any

moment be forced to become our foe; the whole

Western seaboard of Europe from the North Cape

to the Spanish frontier in German hands; all the

ports, all the air-fields on this immense front,

employed against us as potential springboards of

invasion. Moreover, the German air power,

numerically so far outstripping ours, has been

brought so close to our Island that what we used

to dread greatly has come to pass and the

hostile bombers not only reach our shores in a

few minutes and from many directions, but can be

escorted by their fighting aircraft.

Why, Sir, if we had been confronted at the

beginning of May with such a prospect, it would

have seemed incredible that at the end of a

period of horror and disaster, or at this point

in a period of horror and disaster, we should

stand erect, sure of ourselves, masters of our

fate and with the conviction of final victory

burning unquenchable in our hearts. Few would

have believed we could survive; none would have

believed that we should to-day not only feel

stronger but should actually be stronger than we

have ever been before.

Let us see what has happened on the other side

of the scales. The British nation and the

British Empire finding themselves alone, stood

undismayed against disaster. No one flinched or

wavered; nay, some who formerly thought of

peace, now think only of war. Our people are

united and resolved, as they have never been

before. Death and ruin have become small things

compared with the shame of defeat or failure in

duty.

We cannot tell what lies ahead. It may be that

even greater ordeals lie before us. We shall

face whatever is coming to us. We are sure of

ourselves and of our cause and that is the

supreme fact which has emerged in these months

of trial.

Meanwhile, we have not only fortified our hearts

but our Island. We have rearmed and rebuilt our

armies in a degree which would have been deemed

impossible a few months ago. We have ferried

across the Atlantic, in the month of July,

thanks to our friends over there, an immense

mass of munitions of all kinds, cannon, rifles,

machine-guns, cartridges, and shell, all safely

landed without the loss of a gun or a round. The

output of our own factories, working as they

have never worked before, has poured forth to

the troops. The whole British Army is at home.

More than 2,000,000 determined men have rifles

and bayonets in their hands to-night and

three-quarters of them are in regular military

formations. We have never had armies like this

in our Island in time of war. The whole Island

bristles against invaders, from the sea or from

the air.

As I explained to the House in the middle of

June, the stronger our Army at home, the larger

must the invading expedition be, and the larger

the invading expedition, the less difficult will

be the task of the Navy in detecting its

assembly and in intercepting and destroying it

on passage; and the greater also would be the

difficulty of feeding and supplying the invaders

if ever they landed, in the teeth of continuous

naval and air attack on their communications.

All this is classical and venerable doctrine. As

in Nelson's day, the maxim holds, "Our first

line of defense is the enemy's ports." Now air

reconnaissance and photography have brought to

an old principle a new and potent aid.

Our Navy is far stronger than it was at the

beginning of the war. The great flow of new

construction set on foot at the outbreak is now

beginning to come in. We hope our friends across

the ocean will send us a timely reinforcement to

bridge the gap between the peace flotillas of

1939 and the war flotillas of 1941. There is no

difficulty in sending such aid. The seas and

oceans are open. The U-boats are contained. The

magnetic mine is, up to the present time,

effectively mastered. The merchant tonnage under

the British flag, after a year of unlimited

U-boat war, after eight months of intensive

mining attack, is larger than when we began. We

have, in addition, under our control at least

4,000,000 tons of shipping from the captive

countries which has taken refuge here or in the

harbors of the Empire. Our stocks of food of all

kinds are far more abundant than in the days of

peace and a large and growing program of food

production is on foot.

Why do I say all this? Not assuredly to boast;

not assuredly to give the slightest countenance

to complacency. The dangers we face are still

enormous, but so are our advantages and

resources.

I recount them because the people have a right

to know that there are solid grounds for the

confidence which we feel, and that we have good

reason to believe ourselves capable, as I said

in a very dark hour two months ago, of

continuing the war "if necessary alone, if

necessary for years." I say it also because the

fact that the British Empire stands invincible,

and that Nazidom is still being resisted, will

kindle again the spark of hope in the breasts of

hundreds of millions of downtrodden or

despairing men and women throughout Europe, and

far beyond its bounds, and that from these

sparks there will presently come cleansing and

devouring flame.

The great air battle which has been in progress

over this Island for the last few weeks has

recently attained a high intensity. It is too

soon to attempt to assign limits either to its

scale or to its duration. We must certainly

expect that greater efforts will be made by the

enemy than any he has so far put forth. Hostile

air fields are still being developed in France

and the Low Countries, and the movement of

squadrons and material for attacking us is still

proceeding.

It is quite plain that Herr Hitler could not

admit defeat in his air attack on Great Britain

without sustaining most serious injury. If,

after all his boastings and blood-curdling

threats and lurid accounts trumpeted round the

world of the damage he has inflicted, of the

vast numbers of our Air Force he has shot down,

so he says, with so little loss to himself; if

after tales of the panic-stricken British

crushed in their holes cursing the plutocratic

Parliament which has led them to such a plight;

if after all this his whole air onslaught were

forced after a while tamely to peter out, the

Fuehrer's reputation for veracity of statement

might be seriously impugned. We may be sure,

therefore, that he will continue as long as he

has the strength to do so, and as long as any

preoccupations he may have in respect of the

Russian Air Force allow him to do so.

On the other hand, the conditions and course of

the fighting have so far been favorable to us. I

told the House two months ago that whereas in

France our fighter aircraft were wont to inflict

a loss of two or three to one upon the Germans,

and in the fighting at Dunkirk, which was a kind

of no-man's-land, a loss of about three or four

to one, we expected that in an attack on this

Island we should achieve a larger ratio. This

has certainly come true. It must also be

remembered that all the enemy machines and

pilots which are shot down over our Island, or

over the seas which surround it, are either

destroyed or captured; whereas a considerable

proportion of our machines, and also of our

pilots, are saved, and soon again in many cases

come into action.

A vast and admirable system of salvage, directed

by the Ministry of Aircraft Production, ensures

the speediest return to the fighting line of

damaged machines, and the most provident and

speedy use of all the spare parts and material.

At the same time the splendid, nay, astounding

increase in the output and repair of British

aircraft and engines which Lord Beaverbrook has

achieved by a genius of organization and drive,

which looks like magic, has given us overflowing

reserves of every type of aircraft, and an

ever-mounting stream of production both in

quantity and quality.

The enemy is, of course, far more numerous than

we are. But our new production already, as I am

advised, largely exceeds his, and the American

production is only just beginning to flow in. It

is a fact, as I see from my daily returns, that

our bomber and fighter strength now, after all

this fighting, are larger than they have ever

been. We believe that we shall be able to

continue the air struggle indefinitely and as

long as the enemy pleases, and the longer it

continues the more rapid will be our approach,

first towards that parity, and then into that

superiority in the air, upon which in a large

measure the decision of the war depends.

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in

our Empire, and indeed throughout the world,

except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to

the British airmen who, undaunted by odds,

unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal

danger, are turning the tide of the world war by

their prowess and by their devotion. Never in

the field of human conflict was so much owed by

so many to so few.

All hearts go out to the fighter pilots, whose

brilliant actions we see with our own eyes day

after day; but we must never forget that all the

time, night after night, month after month, our

bomber squadrons travel far into Germany, find

their targets in the darkness by the highest

navigational skill, aim their attacks, often

under the heaviest fire, often with serious

loss, with deliberate careful discrimination,

and inflict shattering blows upon the whole of

the technical and war-making structure of the

Nazi power. On no part of the Royal Air Force

does the weight of the war fall more heavily

than on the daylight bombers who will play an

invaluable part in the case of invasion and

whose unflinching zeal it has been necessary in

the meanwhile on numerous occasions to restrain.

We are able to verify the results of bombing

military targets in Germany, not only by reports

which reach us through many sources, but also,

of course, by photography. I have no hesitation

in saying that this process of bombing the

military industries and communications of

Germany and the air bases and storage depots

from which we are attacked, which process will

continue upon an ever-increasing scale until the

end of the war, and may in another year attain

dimensions hitherto undreamed of, affords one at

least of the most certain, if not the shortest

of all the roads to victory. Even if the Nazi

legions stood triumphant on the Black Sea, or

indeed upon the Caspian, even if Hitler was at

the gates of India, it would profit him nothing

if at the same time the entire economic and

scientific apparatus of German war power lay

shattered and pulverized at home.

The fact that the invasion of this Island upon a

large scale has become a far more difficult

operation with every week that has passed since

we saved our Army at Dunkirk, and our very great

preponderance of sea-power enable us to turn our

eyes and to turn our strength increasingly

towards the Mediterranean and against that other

enemy who, without the slightest provocation,

coldly and deliberately, for greed and gain,

stabbed France in the back in the moment of her

agony, and is now marching against us in Africa.

The defection of France has, of course, been

deeply damaging to our position in what is

called, somewhat oddly, the Middle East. In the

defense of Somaliland, for instance, we had

counted upon strong French forces attacking the

Italians from Jibuti. We had counted also upon

the use of the French naval and air bases in the

Mediterranean, and particularly upon the North

African shore. We had counted upon the French

Fleet. Even though metropolitan France was

temporarily overrun, there was no reason why the

French Navy, substantial parts of the French

Army, the French Air Force and the French Empire

overseas should not have continued the struggle

at our side.

Shielded by overwhelming sea-power, possessed of

invaluable strategic bases and of ample funds,

France might have remained one of the great

combatants in the struggle. By so doing, France

would have preserved the continuity of her life,

and the French Empire might have advanced with

the British Empire to the rescue of the

independence and integrity of the French

Motherland.

In our own case, if we had been put in the

terrible position of France, a contingency now

happily impossible, although, of course, it

would have been the duty of all war leaders to

fight on here to the end, it would also have

been their duty, as I indicated in my speech of

4th June, to provide as far as possible for the

Naval security of Canada and our Dominions and

to make sure they had the means to carry the

struggle from beyond the oceans. Most of the

other countries that have been overrun by

Germany for the time being have preserved

valiantly and faithfully. The Czechs, the Poles,

the Norwegians, the Dutch, the Belgians are

still in the field, sword in hand, recognized by

Great Britain and the United States as the sole

representative authorities and lawful

Governments of their respective States.

That France alone should lie prostrate at this

moment, is the crime, not of a great and noble

nation, but of what are called "the men of

Vichy." We have profound sympathy with the

French people. Our old comradeship with France

is not dead. In General de Gaulle and his

gallant band, that comradeship takes an

effective form. These free Frenchmen have been

condemned to death by Vichy, but the day will

come, as surely as the sun will rise to-morrow,

when their names will be held in honor, and

their names will be graven in stone in the

streets and villages of a France restored in a

liberated Europe to its full freedom and its

ancient fame.

But this conviction which I feel of the future

cannot affect the immediate problems which

confront us in the Mediterranean and in Africa.

It had been decided some time before the

beginning of the war not to defend the

Protectorate of Somaliland. That policy was

changed when the French gave in, and when our

small forces there, a few battalions, a few

guns, were attacked by all the Italian troops,

nearly two divisions, which had formerly faced

the French at Jibuti, it was right to withdraw

our detachments, virtually intact, for action

elsewhere. Far larger operations no doubt impend

in the Middle East theatre, and I shall

certainly not attempt to discuss or prophesy

about their probable course. We have large

armies and many means of reinforcing them. We

have the complete sea command of the Eastern

Mediterranean. We intend to do our best to give

a good account of ourselves, and to discharge

faithfully and resolutely all our obligations

and duties in that quarter of the world. More

than that I do not think the House would wish me

to say at the present time.

A good many people have written to me to ask me

to make on this occasion a fuller statement of

our war aims, and of the kind of peace we wish

to make after the war, than is contained in the

very considerable declaration which was made

early in the Autumn. Since then we have made

common cause with Norway, Holland, and Belgium.

We have recognized the Czech Government of Dr.

Benes, and we have told General de Gaulle that

our success will carry with it the restoration

of France.

I do not think it would be wise at this moment,

while the battle rages and the war is still

perhaps only in its earlier stage, to embark

upon elaborate speculations about the future

shape which should be given to Europe or the new

securities which must be arranged to spare

mankind the miseries of a third World War. The

ground is not new, it has been frequently

traversed and explored, and many ideas are held

about it in common by all good men, and all free

men. But before we can undertake the task of

rebuilding we have not only to be convinced

ourselves, but we have to convince all other

countries that the Nazi tyranny is going to be

finally broken.

The right to guide the course of world history

is the noblest prize of victory. We are still

toiling up the hill; we have not yet reached the

crest-line of it; we cannot survey the landscape

or even imagine what its condition will be when

that longed-for morning comes. The task which

lies before us immediately is at once more

practical, more simple and more stern. I hope -

indeed I pray - that we shall not be found

unworthy of our victory if after toil and

tribulation it is granted to us. For the rest,

we have to gain the victory. That is our task.

There is, however, one direction in which we can

see a little more clearly ahead. We have to

think not only for ourselves but for the lasting

security of the cause and principles for which

we are fighting and of the long future of the

British Commonwealth of Nations.

Some months ago we came to the conclusion that

the interests of the United States and of the

British Empire both required that the United

States should have facilities for the naval and

air defense of the Western hemisphere against

the attack of a Nazi power which might have

acquired temporary but lengthy control of a

large part of Western Europe and its formidable

resources.

We had therefore decided spontaneously, and

without being asked or offered any inducement,

to inform the Government of the United States

that we would be glad to place such defense

facilities at their disposal by leasing suitable

sites in our Transatlantic possessions for their

greater security against the unmeasured dangers

of the future.

The principle of association of interests for

common purposes between Great Britain and the

United States had developed even before the war.

Various agreements had been reached about

certain small islands in the Pacific Ocean which

had become important as air fuelling points. In

all this line of thought we found ourselves in

very close harmony with the Government of

Canada.

Presently we learned that anxiety was also felt

in the United States about the air and naval

defense of their Atlantic seaboard, and

President Roosevelt has recently made it clear

that he would like to discuss with us, and with

the Dominion of Canada and with Newfoundland,

the development of American naval and air

facilities in Newfoundland and in the West

Indies. There is, of course, no question of any

transference of sovereignty - that has never

been suggested - or of any action being taken,

without the consent or against the wishes of the

various Colonies concerned, but for our part,

His Majesty's Government are entirely willing to

accord defense facilities to the United States

on a 99 years' leasehold basis, and we feel sure

that our interests no less than theirs, and the

interests of the Colonies themselves and of

Canada and Newfoundland will be served thereby.

These are important steps. Undoubtedly this

process means that these two great organizations

of the English-speaking democracies, the British

Empire and the United States, will have to be

somewhat mixed up together in some of their

affairs for mutual and general advantage.

For my own part, looking out upon the future, I

do not view the process with any misgivings. I

could not stop it if I wished; no one can stop

it. Like the Mississippi, it just keeps rolling

along. Let it roll. Let it roll on full flood,

inexorable, irresistible, benignant, to broader

lands and better days.

More History

|

|