|

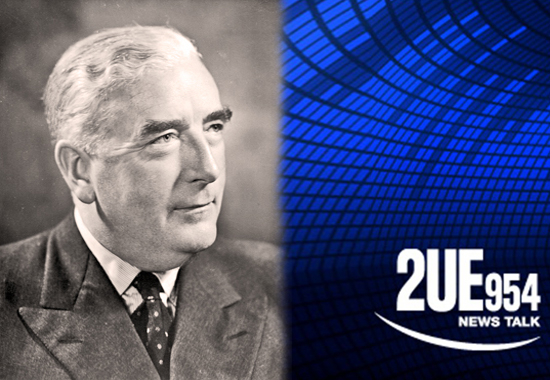

ROBERT MENZIES BROADCASTS ON STATION

2UE, SYDNEY - 1942

The Forgotten People

It follows the full text transcript of

Robert Menzies' The Forgotten People

speech, broadcast from Sydney, Australia — May 22, 1942.

|

Quite recently, |

a bishop wrote a

letter to a great daily newspaper. His theme was

the importance of doing justice to the workers.

His belief, apparently, was that the workers are

those who work with their hands. He sought to

divide the people of Australia into classes. He

was obviously suffering from what has for years

seemed to me to be our greatest political

disease - the disease of thinking that the

community is divided into the rich and

relatively idle, and the laborious poor, and

that every social and political controversy can

be resolved into the question: What side are you

on?

Now, the last thing that I want to do is to

commence or take part in a false war of this

kind. In a country like Australia the class war

must always be a false war. But if we are to

talk of classes, then the time has come to say

something of the forgotten class - the middle

class - those people who are constantly in

danger of being ground between the upper and the

nether millstones of the false class war; the

middle class who, properly regarded, represent

the backbone of this country.

We do not have classes here as in England, and

therefore the terms do not mean the same; so I

must define what I mean when I use the

expression "middle classí.

Let me first define it by exclusion. I exclude

at one end of the scale the rich and powerful:

those who control great funds and enterprises,

and are as a rule able to protect themselves -

though it must be said that in a political sense

they have as a rule shown neither comprehension

nor competence. But I exclude them because in

most material difficulties, the rich can look

after themselves.

I exclude at the other end of the scale the mass

of unskilled people, almost invariably

well-organized, and with their wages and

conditions protected by popular law. What I am

excluding them from is my definition of middle

class. We cannot exclude them from the problem

of social progress, for one of the prime objects

of modern social and political policy is to give

to them a proper measure of security, and

provide the conditions which will enable them to

acquire skill and knowledge and individuality.

These exclusions being made, I include the

intervening range - the kind of people I myself

represent in Parliament - salary earners,

shopkeepers, skilled artisans, professional men

and women, farmers, and so on. These are, in the

political and economic sense, the middle class.

They are for the most part unorganized and

unselfconscious. They are envied by those whose

social benefits are largely obtained by taxing

them. They are not rich enough to have

individual power. They are taken for granted by

each political party in turn. They are not

sufficiently lacking in individualism to be

organized for what in these days we call

"pressure politics". And yet, as I have said,

they are the backbone of the nation.

The communist has always hated what he calls the

"bourgeoisie", because he sees clearly that the

existence of one has kept British countries from

revolution, while the substantial absence of one

in feudal France at the end of the eighteenth

century and in Tsarist Russia at the end of the

last war made revolution easy and indeed

inevitable.

You may say to me, "Why bring this matter up at

this stage, when we are fighting a war in the

result of which we are all equally concerned?"

My answer is that I am bringing it up because

under the pressures of war we may, if we are not

careful - if we are not as thoughtful as the

times will permit us to be - inflict a fatal

injury upon our own backbone.

In point of political, industrial and social

theory and practice there are great delays in

time of war. But there are also great

accelerations. We must watch each, remembering

always that whether we know it or not, and

whether we like it or not, the foundations of

whatever new order is to come after the war are

inevitably being laid down now. We cannot go

wrong right up to the peace treaty and expect

suddenly thereafter to go right.

Now, what is the value of this middle class, so

defined and described? First, it has "a stake in

the country". It has responsibility for homes -

homes material, homes human, homes spiritual.

I do not believe that the real life of this

nation is to be found either in great luxury

hotels and the petty gossip of so-called

fashionable suburbs, or in the officialdom of

organized masses. It is to be found in the homes

of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and

who, whatever their individual religious

conviction or dogma, see in their children their

greatest contribution to the immortality of

their race. The home is the foundation of sanity

and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition

of continuity; its health determines the health

of society as a whole.

I have mentioned homes material, homes human,

and homes spiritual. Let me take them in their

order. What do I mean by "homes material"?

The material home represents the concrete

expression of the habits of frugality and saving

"for a home of our own". Your advanced socialist

may rage against private property even while he

acquires it; but one of the best instincts in us

is that which induces us to have one little

piece of earth with a house and a garden which

is ours: to which we can withdraw, in which we

can be among our friends, into which no stranger

may come against our will.

If you consider it, you will see that if, as in

the old saying, "the Englishmanís home is his

castle", it is this very fact that leads on to

the conclusion that he who seeks to violate that

law by violating the soil of England must be

repelled and defeated.

National patriotism, in other words, inevitably

springs from the instinct to defend and preserve

our own homes.

Then we have homes human. A great house, full of

loneliness, is not a home. "Stone walls do not a

prison make", not do they make a house. They may

equally make a stable or a piggery. Brick walls,

dormer windows and central heating need not make

more than a hotel. My home is where my wife and

children are. The instinct to be with them is

the great instinct of civilized man; the

instinct to give them a chance in life - to make

them not leaners but lifters - is a noble

instinct.

If Scotland has made a great contribution to the

theory and practice of education, it is because

of the tradition of Scottish homes. The Scottish

ploughman, walking behind his team, cons ways

and means of making his son a farmer, and so he

sends him to the village school. The Scottish

farmer ponders upon the future of his son, and

sees it most assured not by the inheritance of

money but by the acquisition of that knowledge

which will give him power; and so the sons of

many Scottish farmers find their way to

Edinburgh and a university degree.

The great question is, "How can I qualify my son

to help society?" Not, as we have so frequently

thought, "How can I qualify society to help my

son?" If human homes are to fulfill their

destiny, then we must have frugality and saving

for education and progress.

And finally, we have homes spiritual. This is a

notion which finds its simplest and most moving

expression in "The Cotterís Saturday Night" of

Burns. Human nature is at its greatest when it

combines dependence upon God with independence

of man.

We offer no affront - on the contrary we have

nothing but the warmest human compassion -

towards those whom fate has compelled to live

upon the bounty of the State, when we say that

the greatest element in a strong people is a

fierce independence of spirit. This is the only

real freedom, and it has as its corollary a

brave acceptance of unclouded individual

responsibility. The moment a man seeks moral and

intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd,

he ceases to be a human being and becomes a

cipher. The home spiritual so understood is not

produced by lassitude or by dependence; it is

produced by self-sacrifice, by frugality and

saving.

In a war, as indeed at most times, we become the

ready victims of phrases. We speak glibly of may

things without pausing to consider what they

signify. We speak of "financial power",

forgetting that the financial power of 1942 is

based upon the savings of generations which have

preceded it. We speak of "morale" as if it were

a quality induced from without - created by

others for our benefit - when in truth there can

be no national morale which is not based upon

the individual courage of men and women. We

speak of "man power" as if it were a mere matter

of arithmetic: as if it were made up of a

multiplication of men and muscles without

spirit.

Second, the middle class, more than any other,

provides the intelligent ambition which is the

motive power of human progress. The idea

entertained by many people that, in a

well-constituted world, we shall all live on the

State in the quintessence of madness, for what

is the State but us ? We collectively must

provide what we individually receive.

The great vice of democracy - a vice which is

exacting a bitter retribution from it at this

moment - is that for a generation we have been

busy getting ourselves on to the list of

beneficiaries and removing ourselves from the

list of contributors, as if somewhere there was

somebody elseís wealth and somebody elseís

effort on which we could thrive.

To discourage ambition, to envy success, to hate

achieved superiority, to distrust independent

thought, to sneer at and impute false motives to

public service - these are the maladies of

modern democracy, and of Australian democracy in

particular. Yet ambition, effort, thinking, and

readiness to serve are not only the design and

objectives of self-government but are the

essential conditions of its success. If this is

not so, then we had better put back the clock,

and search for a benevolent autocracy once more.

Where do we find these great elements most

commonly? Among the defensive and comfortable

rich, among the unthinking and unskilled mass,

or among what I have called the "middle class"?

Third, the middle class provides more than

perhaps any other the intellectual life which

marks us off from the beast: the life which

finds room for literature, for the arts, for

science, for medicine and the law.

Consider the case of literature and art. Could

these survive as a department of State? Are we

to publish our poets according to their

political color? Is the State to decree

surrealism because surrealism gets a heavy vote

in a key electorate? The truth is that no great

book was ever written and no great picture ever

painted by the clock or according to civil

service rules. These things are done by man, not

men. You cannot regiment them. They require

opportunity, and sometimes leisure. The artist,

if he is to live, must have a buyer; the writer

an audience. He finds them among frugal people

to whom the margin above bare living means a

chance to reach out a little towards that heaven

which is just beyond our grasp. It has always

seemed to me, for example, that an artist is

better helped by the man who sacrifices

something to buy a picture he loves than by a

rich patron who follows the fashion.

Fourth, this middle class maintains and fills

the higher schools and universities, and so

feeds the lamp of learning.

What are schools for? To train people for

examinations, to enable people to comply with

the law, or to produce developed men and women?

Are the universities mere technical schools, or

have they as one of their functions the

preservation of pure learning, bringing in its

train not merely riches for the imagination but

a comparative sense for the mind, and leading to

what we need so badly - the recognition of

values which are other than pecuniary?

One of the great blots on our modern living is

the cult of false values, a repeated application

of the test of money, notoriety, applause. A

world in which a comedian or a beautiful

half-wit on the screen can be paid fabulous

sums, whilst scientific researchers and

discoverers can suffer neglect and starvation,

is a world which needs to have its sense of

values violently set right.

Now, have we realized and recognized these

things, or is most of our policy designed to

discourage or penalize thrift, to encourage

dependence on the State, to bring about a dull

equality on the fantastic idea that all men are

equal in mind and needs and deserts: to level

down by taking the mountains our of the

landscape, to weigh men according to their

political organizations and power - as votes and

not as human beings? These are formidable

questions, and we cannot escape from answering

them if there is really to be a new order for

the world.

I have been actively engaged in politics for

fourteen years in the State of Victoria and in

the Commonwealth of Australia. In that period I

cannot readily recall many occasions upon which

any policy was pursued which was designed to

help the thrifty, to encourage independence, to

recognize the divine and valuable variations of

menís minds. On the contrary, there have been

many instances in which the votes of the

thriftless have been used to defeat the thrifty.

On occasions of emergency, as in the depression

and during the war, we have hastened to make it

clear that the provision made by man for his own

retirement and old age is not half as sacrosanct

as the provision the State would have made for

him had he never saved at all.

We have talked of income from savings as if it

possessed a somewhat discreditable character. We

have taxed it more and more heavily. We have

spoken slightingly of the earning of interest at

the very moment when we have advocated new

pensions and social schemes. I have myself heard

a minister of power and influence declare that

no deprivation is suffered by a man if he still

has the means to fill his stomach, clothe his

body and keep a roof over his head. And yet the

truth is, as I have endeavored to show, that

frugal people who strive for and obtain the

margin above these materially necessary things

are the whole foundation of a really active and

developing national life.

The case for the middle class is the case for a

dynamic democracy as against a stagnant one.

Stagnant waters are level, and in them the scum

rises. Active waters are never level; they toss

and tumble and have crests and troughs; but the

scientists tell us that they purify themselves

in a few hundred yards.

That we are all, as human souls, of like value

cannot be denied. That each of us should have

his chance is and must be the great objective of

political and social policy. But to say that the

industrious and intelligent son of

self-sacrificing and saving and forward-looking

parents has the same social deserts and even

material needs as the dull offspring of stupid

and improvident parents is absurd.

If the motto is to be, "Eat, drink and be merry,

for tomorrow you will die, and if it chances you

donít die, the State will look after you; but if

you donít eat, drink and be merry, and save, we

shall take your savings from you", then the

whole business of life will become

foundationless.

Are you looking forward to a breed of men after

the war who will have become boneless wonders?

Leaners grow flabby; lifters grow muscles. Men

without ambition readily become slaves. Indeed,

there is much more slavery in Australia than

most people imagine. How many hundreds of

thousands of us are slaves to greed, to fear, to

newspapers, to public opinion - represented by

the accumulated views of our neighbors! Landless

men smell the vapors of the street corner.

Landed men smell the brown earth, and plant

their feet upon it and know that it is good.

To all of this many of my friends will retort,

"Ah, thatís all very well, but when this war is

over the levelers will have won the day." My

answer is that, on the contrary, men will come

out of this war as gloriously unequal in many

things as when they entered it. Much wealth will

have been destroyed; inherited riches will be

suspect; a fellowship of suffering, if we really

experience it, will have opened many hearts and

perhaps closed many mouths. Many great edifices

will have fallen, and we shall be able to study

foundations as never before, because the war

will have exposed them.

But I do not believe that we shall come out into

the over-lordship of an all-powerful State on

whose benevolence we shall live, spineless and

effortless - a State which will dole out bread

and ideas with neatly regulated accuracy; where

we shall all have our dividend without

subscribing our capital; where the Government,

that almost deity, will nurse us and rear us and

maintain us and pension us and bury us; where we

shall all be civil servants, and all presumably,

since we are equal, heads of departments.

If the new world is to be a world of men, we

must be not pallid and bloodless ghosts, but a

community of people whose motto shall be, "To

strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield".

Individual enterprise must drive us forward.

That does not mean that we are to return to the

old and selfish notions of laissez-faire. The

functions of the State will be much more than

merely keeping the ring within which the

competitors will fight. Our social and

industrial obligations will be increased. There

will be more law, not less; more control, not

less.

But what really happens to us will depend on how

many people we have who are of the great and

sober and dynamic middle-class - the strivers,

the planners, the ambitious ones. We shall

destroy them at our peril.

More History

|

|