|

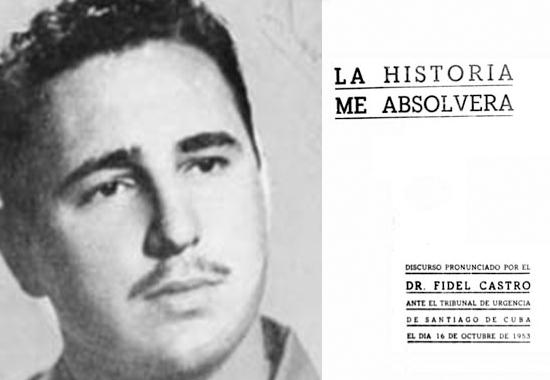

ARCHIVING MOMENTARY SET-BACKS FOR

FUTURE PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL - FIDEL

CASTRO 1953

History Will Absolve Me

Go here for more about

Fidel Castro.

Fidel Castro.

Go here for more about

Fidel Castro's History Will Absolve Me

speech.

Fidel Castro's History Will Absolve Me

speech.

Go here for the

Spanish version of this speech.

Spanish version of this speech.

It follows the English

translation of the full text transcript of Fidel Castro's

History Will Absolve Me speech, delivered at Santiago de

Cuba - October 16, 1953.

This is page 1 of

2. Go to

page 2 of this speech.

page 2 of this speech.

|

Honorable Judges, |

Never has a lawyer

had to practice his profession under such

difficult conditions; never has such a number of

overwhelming irregularities been committed

against an accused man. In this case, counsel

and defendant are one and the same. As attorney

he has not even been able to take a look at the

indictment. As accused, for the past seventy-six

days he has been locked away in solitary

confinement, held totally and absolutely

incommunicado, in violation of every human and

legal right.

He who speaks to you hates vanity with all his

being, nor are his temperament or frame of mind

inclined towards courtroom poses or

sensationalism of any kind. If I have had to

assume my own defense before this Court it is

for two reasons. First, because I have been

denied legal aid almost entirely. And second,

only one who has been so deeply wounded, who has

seen his country so forsaken and its justice

trampled so, can speak at a moment like this

with words that spring from the blood of his

heart and the truth of his very gut.

There was no lack of generous comrades who

wished to defend me, and the Havana Bar

Association appointed a courageous and competent

jurist, Dr. Jorge Pagliery, Dean of the Bar in

this city, to represent me in this case.

However, he was not permitted to carry out his

task. As often as he tried to see me, the prison

gates were closed before him. Only after a month

and a half, and through the intervention of the

Court, was he finally granted a ten minute

interview with me in the presence of a sergeant

from the Military Intelligence Agency (SIM). One

supposes that a lawyer has a right to speak with

his defendant in private, and this right is

respected throughout the world, except in the

case of a Cuban prisoner of war in the hands of

an implacable tyranny that abides by no code of

law, be it legal or humane. Neither Dr. Pagliery

nor I were willing to tolerate such dirty spying

upon our means of defense for the oral trial.

Did they want to know, perhaps, beforehand, the

methods we would use in order to reduce to dust

the incredible fabric of lies they had woven

around the Moncada Barracks events? How were we

going to expose the terrible truth they would go

to such great lengths to conceal? It was then

that we decided that, taking advantage of my

professional rights as a lawyer, I would assume

my own defense.

This decision, overheard by the sergeant and

reported by him to his superior, provoked a real

panic. It looked like some mocking little imp

was telling them that I was going to ruin all

their plans. You know very well, Honorable

Judges, how much pressure has been brought to

bear on me in order to strip me as well of this

right that is ratified by long Cuban tradition.

The Court could not give in to such machination

for that would have left the accused in a state

of total indefensiveness. The accused, who is

now exercising this right to plead his own case,

will under no circumstances refrain from saying

what he must say. I consider it essential that I

explain, at the onset, the reason for the

terrible isolation in which I have been kept;

what was the purpose of keeping me silent; what

was behind the plots to kill me, plots which the

Court is familiar with; what grave events are

being hidden from the people; and the truth

behind all the strange things which have taken

place during this trial. I propose to do all

this with utmost clarity.

You have publicly called this case the most

significant in the history of the Republic. If

you sincerely believed this, you should not have

allowed your authority to be stained and

degraded. The first court session was September

21st. Among one hundred machine guns and

bayonets, scandalously invading the hall of

justice, more than a hundred people were seated

in the prisoner's dock. The great majority had

nothing to do with what had happened. They had

been under preventive arrest for many days,

suffering all kinds of insults and abuses in the

chambers of the repressive units. But the rest

of the accused, the minority, were brave and

determined, ready to proudly confirm their part

in the battle for freedom, ready to offer an

example of unprecedented self-sacrifice and to

wrench from the jail's claws those who in

deliberate bad faith had been included in the

trial. Those who had met in combat confronted

one another again. Once again, with the cause of

justice on our side, we would wage the terrible

battle of truth against infamy! Surely the

regime was not prepared for the moral

catastrophe in store for it!

How to maintain all its false accusations? How

to keep secret what had really happened, when so

many young men were willing to risk everything -

prison, torture and death, if necessary - in

order that the truth be told before this Court?

I was called as a witness at that first session.

For two hours I was questioned by the Prosecutor

as well as by twenty defense attorneys. I was

able to prove with exact facts and figures the

sums of money that had been spent, the way this

money was collected and the arms we had been

able to round up. I had nothing to hide, for the

truth was: all this was accomplished through

sacrifices without precedent in the history of

our Republic. I spoke of the goals that inspired

us in our struggle and of the humane and

generous treatment that we had at all times

accorded our adversaries. If I accomplished my

purpose of demonstrating that those who were

falsely implicated in this trial were neither

directly nor indirectly involved, I owe it to

the complete support and backing of my heroic

comrades. For, as I said, the consequences they

might be forced to suffer at no time caused them

to repent of their condition as revolutionaries

and patriots, I was never once allowed to speak

with these comrades of mine during the time we

were in prison, and yet we planned to do exactly

the same. The fact is, when men carry the same

ideals in their hearts, nothing can isolate them

- neither prison walls nor the sod of

cemeteries. For a single memory, a single

spirit, a single idea, a single conscience, a

single dignity will sustain them all.

From that moment on, the structure of lies the

regime had erected about the events at Moncada

Barracks began to collapse like a house of

cards. As a result, the Prosecutor realized that

keeping all those persons named as instigators

in prison was completely absurd, and he

requested their provisional release.

At the close of my testimony in that first

session, I asked the Court to allow me to leave

the dock and sit among the counsel for the

defense. This permission was granted. At that

point what I consider my most important mission

in this trial began: to totally discredit the

cowardly, miserable and treacherous lies which

the regime had hurled against our fighters; to

reveal with irrefutable evidence the horrible,

repulsive crimes they had practiced on the

prisoners; and to show the nation and the world

the infinite misfortune of the Cuban people who

are suffering the cruelest, the most inhuman

oppression of their history.

The second session convened on Tuesday,

September 22nd. By that time only ten witnesses

had testified, and they had already cleared up

the murders in the Manzanillo area, specifically

establishing and placing on record the direct

responsibility of the captain commanding that

post. There were three hundred more witnesses to

testify. What would happen if, with a staggering

mass of facts and evidence, I should proceed to

cross-examine the very Army men who were

directly responsible for those crimes? Could the

regime permit me to go ahead before the large

audience attending the trial? Before journalists

and jurists from all over the island? And before

the party leaders of the opposition, who they

had stupidly seated right in the prisoner's dock

where they could hear so well all that might be

brought out here? They would rather have blown

up the court house, with all its judges, than

allow that!

And so they devised a plan by which they could

eliminate me from the trial and they proceeded

to do just that, manu militari. On Friday night,

September 25th, on the eve of the third session

of the trial, two prison doctors visited me in

my cell. They were visibly embarrassed. 'We have

come to examine you,' they said. I asked them,

'Who is so worried about my health?' Actually,

from the moment I saw them I realized what they

had come for. They could not have treated me

with greater respect, and they explained their

predicament to me. That afternoon Colonel

Chaviano had appeared at the prison and told

them I 'was doing the Government terrible damage

with this trial.' He had told them they must

sign a certificate declaring that I was ill and

was, therefore, unable to appear in court. The

doctors told me that for their part they were

prepared to resign from their posts and risk

persecution. They put the matter in my hands,

for me to decide. I found it hard to ask those

men to unhesitatingly destroy themselves. But

neither could I, under any circumstances,

consent that those orders be carried out.

Leaving the matter to their own consciences, I

told them only: 'You must know your duty; I

certainly know mine.'

After leaving the cell they signed the

certificate. I know they did so believing in

good faith that this was the only way they could

save my life, which they considered to be in

grave danger. I was not obliged to keep our

conversation secret, for I am bound only by the

truth. Telling the truth in this instance may

jeopardize those good doctors in their material

interests, but I am removing all doubt about

their honor, which is worth much more. That same

night, I wrote the Court a letter denouncing the

plot; requesting that two Court physicians be

sent to certify my excellent state of health,

and to inform you that if to save my life I must

take part in such deception, I would a thousand

times prefer to lose it. To show my

determination to fight alone against this whole

degenerate frame-up, I added to my own words one

of the Master's lines: 'A just cause even from

the depths of a cave can do more than an army.'

As the Court knows, this was the letter Dr.

Melba Hernández submitted at the third session

of the trial on September 26th. I managed to get

it to her in spite of the heavy guard I was

under. That letter, of course, provoked

immediate reprisals. Dr. Hernández was subjected

to solitary confinement, and I - since I was

already incommunicado - was sent to the most

inaccessible reaches of the prison. From that

moment on, all the accused were thoroughly

searched from head to foot before they were

brought into the courtroom.

Two Court physicians certified on September 27th

that I was, in fact, in perfect health. Yet, in

spite of the repeated orders from the Court, I

was never again brought to the hearings. What's

more, anonymous persons daily circulated

hundreds of apocryphal pamphlets which announced

my rescue from jail. This stupid alibi was

invented so they could physically eliminate me

and pretend I had tried to escape. Since the

scheme failed as a result of timely exposure by

ever alert friends, and after the first

affidavit was shown to be false, the regime

could only keep me away from the trial by open

and shameless contempt of Court.

This was an incredible situation, Honorable

Judges: Here was a regime literally afraid to

bring an accused man to Court; a regime of blood

and terror that shrank in fear of the moral

conviction of a defenseless man - unarmed,

slandered and isolated. And so, after depriving

me of everything else, they finally deprived me

even of the trial in which I was the main

accused. Remember that this was during a period

in which individual rights were suspended and

the Public Order Act as well as censorship of

radio and press were in full force. What

unbelievable crimes this regime must have

committed to so fear the voice of one accused

man!

I must dwell upon the insolence and disrespect

which the Army leaders have at all times shown

towards you. As often as this Court has ordered

an end to the inhuman isolation in which I was

held; as often as it has ordered my most

elementary rights to be respected; as often as

it has demanded that I be brought before it,

this Court has never been obeyed! Worse yet: in

the very presence of the Court, during the first

and second hearings, a praetorian guard was

stationed beside me to totally prevent me from

speaking to anyone, even among the brief

recesses. In other words, not only in prison,

but also in the courtroom and in your presence,

they ignored your decrees. I had intended to

mention this matter in the following session, as

a question of elementary respect for the Court,

but - I was never brought back. And if, in

exchange for so much disrespect, they bring us

before you to be jailed in the name of a

legality which they and they alone have been

violating since March 10th, sad indeed is the

role they would force on you. The Latin maxim

Cedant arma togae has certainly not been

fulfilled on a single occasion during this

trial. I beg you to keep that circumstance well

in mind.

What is more, these devices were in any case

quite useless; my brave comrades, with

unprecedented patriotism, did their duty to the

utmost.

'Yes, we set out to fight for Cuba's freedom and

we are not ashamed of having done so,' they

declared, one by one, on the witness stand.

Then, addressing the Court with impressive

courage, they denounced the hideous crimes

committed upon the bodies of our brothers.

Although absent from Court, I was able, in my

prison cell, to follow the trial in all its

details. And I have the convicts at Boniato

Prison to thank for this. In spite of all

threats, these men found ingenious means of

getting newspaper clippings and all kinds of

information to me. In this way they avenged the

abuses and immoralities perpetrated against them

both by Taboada, the warden, and the supervisor,

Lieutenant Rozabal, who drove them from sun up

to sun down building private mansions and

starved them by embezzling the prison food

budget.

As the trial went on, the roles were reversed:

those who came to accuse found themselves

accused, and the accused became the accusers! It

was not the revolutionaries who were judged

there; judged once and forever was a man named

Batista - monstruum horrendum! - and it matters

little that these valiant and worthy young men

have been condemned, if tomorrow the people will

condemn the Dictator and his henchmen! Our men

were consigned to the Isle of Pines Prison, in

whose circular galleries Castells' ghost still

lingers and where the cries of countless victims

still echo; there our young men have been sent

to expiate their love of liberty, in bitter

confinement, banished from society, torn from

their homes and exiled from their country. Is it

not clear to you, as I have said before, that in

such circumstances it is difficult and

disagreeable for this lawyer to fulfill his

duty?

As a result of so many turbid and illegal

machinations, due to the will of those who

govern and the weakness of those who judge, I

find myself here in this little room at the

Civilian Hospital, where I have been brought to

be tried in secret, so that I may not be heard

and my voice may be stifled, and so that no one

may learn of the things I am going to say. Why,

then, do we need that imposing Palace of Justice

which the Honorable Judges would without doubt

find much more comfortable? I must warn you: it

is unwise to administer justice from a hospital

room, surrounded by sentinels with fixed

bayonets; the citizens might suppose that our

justice is sick - and that it is captive.

Let me remind you, your laws of procedure

provide that trials shall be 'public hearings;'

however, the people have been barred altogether

from this session of Court. The only civilians

admitted here have been two attorneys and six

reporters, in whose newspapers the censorship of

the press will prevent printing a word I say. I

see, as my sole audience in this chamber and in

the corridors, nearly a hundred soldiers and

officers. I am grateful for the polite and

serious attention they give me. I only wish I

could have the whole Army before me! I know, one

day, this Army will seethe with rage to wash

away the terrible, the shameful bloodstains

splattered across the military uniform by the

present ruthless clique in its lust for power.

On that day, oh what a fall awaits those mounted

in arrogance on their noble steeds! - provided

that the people have not dismounted them long

before that!

Finally, I should like to add that no treatise

on penal law was allowed me in my cell. I have

at my disposal only this tiny code of law lent

to me by my learned counsel, Dr. Baudillo

Castellanos, the courageous defender of my

comrades. In the same way they prevented me from

receiving the books of Martí; it seems the

prison censorship considered them too

subversive. Or is it because I said Martí was

the inspirer of the 26th of July? Reference

books on any other subject were also denied me

during this trial. But it makes no difference! I

carry the teachings of the Master in my heart,

and in my mind the noble ideas of all men who

have defended people's freedom everywhere!

I am going to make only one request of this

court; I trust it will be granted as a

compensation for the many abuses and outrages

the accused has had to tolerate without

protection of the law. I ask that my right to

express myself be respected without restraint.

Otherwise, even the merest semblance of justice

cannot be maintained, and the final episode of

this trial would be, more than all the others,

one of ignominy and cowardice.

I must admit that I am somewhat disappointed. I

had expected that the Honorable Prosecutor would

come forward with a grave accusation. I thought

he would be ready to justify to the limit his

contention, and his reasons why I should be

condemned in the name of Law and Justice - what

law and what justice? - to 26 years in prison.

But no. He has limited himself to reading

Article 148 of the Social Defense Code. On the

basis of this, plus aggravating circumstances,

he requests that I be imprisoned for the lengthy

term of 26 years! Two minutes seems a very short

time in which to demand and justify that a man

be put behind bars for more than a quarter of a

century. Can it be that the Honorable Prosecutor

is, perhaps, annoyed with the Court? Because as

I see it, his laconic attitude in this case

clashes with the solemnity with which the

Honorable Judges declared, rather proudly, that

this was a trial of the greatest importance! I

have heard prosecutors speak ten times longer in

a simple narcotics case asking for a sentence of

just six months. The Honorable Prosecutor has

supplied not a word in support of his petition.

I am a just man. I realize that for a

prosecuting attorney under oath of loyalty to

the Constitution of the Republic, it is

difficult to come here in the name of an

unconstitutional, statutory, de facto

government, lacking any legal much less moral

basis, to ask that a young Cuban, a lawyer like

himself - perhaps as honorable as he, be sent to

jail for 26 years. But the Honorable Prosecutor

is a gifted man and I have seen much less

talented persons write lengthy diatribes in

defense of this regime. How then can I suppose

that he lacks reason with which to defend it, at

least for fifteen minutes, however contemptible

that might be to any decent person? It is clear

that there is a great conspiracy behind all

this.

Honorable Judges: Why such interest in silencing

me? Why is every type of argument foregone in

order to avoid presenting any target whatsoever

against which I might direct my own brief? Is it

that they lack any legal, moral or political

basis on which to put forth a serious

formulation of the question? Are they that

afraid of the truth? Do they hope that I, too,

will speak for only two minutes and that I will

not touch upon the points which have caused

certain people sleepless nights since July 26th?

Since the prosecutor's petition was restricted

to the mere reading of five lines of an article

of the Social Defense Code, might they suppose

that I too would limit myself to those same

lines and circle round them like some slave

turning a millstone? I shall by no means accept

such a gag, for in this trial there is much more

than the freedom of a single individual at

stake. Fundamental matters of principle are

being debated here, the right of men to be free

is on trial, the very foundations of our

existence as a civilized and democratic nation

are in the balance. When this trial is over, I

do not want to have to reproach myself for any

principle left undefended, for any truth left

unsaid, for any crime not denounced.

The Honorable Prosecutor's famous little article

hardly deserves a minute of my time. I shall

limit myself for the moment to a brief legal

skirmish against it, because I want to clear the

field for an assault against all the endless

lies and deceits, the hypocrisy, conventionalism

and moral cowardice that have set the stage for

the crude comedy which since the 10th of March -

and even before then - has been called Justice

in Cuba.

It is a fundamental principle of criminal law

that an imputed offense must correspond exactly

to the type of crime described by law. If no law

applies exactly to the point in question, then

there is no offense.

The article in question reads textually: 'A

penalty of imprisonment of from three to ten

years shall be imposed upon the perpetrator of

any act aimed at bringing about an armed

uprising against the Constitutional Powers of

the State. The penalty shall be imprisonment for

from five to twenty years, in the event that

insurrection actually be carried into effect.'

In what country is the Honorable Prosecutor

living? Who has told him that we have sought to

bring about an uprising against the

Constitutional Powers of the State? Two things

are self-evident. First of all, the dictatorship

that oppresses the nation is not a

constitutional power, but an unconstitutional

one: it was established against the

Constitution, over the head of the Constitution,

violating the legitimate Constitution of the

Republic. The legitimate Constitution is that

which emanates directly from a sovereign people.

I shall demonstrate this point fully later on,

notwithstanding all the subterfuges contrived by

cowards and traitors to justify the

unjustifiable. Secondly, the article refers to

Powers, in the plural, as in the case of a

republic governed by a Legislative Power, an

Executive Power, and a Judicial Power which

balance and counterbalance one another. We have

fomented a rebellion against one single power,

an illegal one, which has usurped and merged

into a single whole both the Legislative and

Executive Powers of the nation, and so has

destroyed the entire system that was

specifically safeguarded by the Code now under

our analysis. As to the independence of the

Judiciary after the 10th of March, I shall not

allude to that for I am in no mood for joking

... No matter how Article 148 may be stretched,

shrunk or amended, not a single comma applies to

the events of July 26th. Let us leave this

statute alone and await the opportunity to apply

it to those who really did foment an uprising

against the Constitutional Powers of the State.

Later I shall come back to the Code to refresh

the Honorable Prosecutor's memory about certain

circumstances he has unfortunately overlooked.

I warn you, I am just beginning! If there is in

your hearts a vestige of love for your country,

love for humanity, love for justice, listen

carefully. I know that I will be silenced for

many years; I know that the regime will try to

suppress the truth by all possible means; I know

that there will be a conspiracy to bury me in

oblivion. But my voice will not be stifled - it

will rise from my breast even when I feel most

alone, and my heart will give it all the fire

that callous cowards deny it.

From a shack in the mountains on Monday, July

27th, I listened to the dictator's voice on the

air while there were still 18 of our men in arms

against the government. Those who have never

experienced similar moments will never know that

kind of bitterness and indignation. While the

long-cherished hopes of freeing our people lay

in ruins about us we heard those crushed hopes

gloated over by a tyrant more vicious, more

arrogant than ever. The endless stream of lies

and slanders, poured forth in his crude, odious,

repulsive language, may only be compared to the

endless stream of clean young blood which had

flowed since the previous night - with his

knowledge, consent, complicity and approval -

being spilled by the most inhuman gang of

assassins it is possible to imagine. To have

believed him for a single moment would have

sufficed to fill a man of conscience with

remorse and shame for the rest of his life. At

that time I could not even hope to brand his

miserable forehead with the mark of truth which

condemns him for the rest of his days and for

all time to come. Already a circle of more than

a thousand men, armed with weapons more powerful

than ours and with peremptory orders to bring in

our bodies, was closing in around us. Now that

the truth is coming out, now that speaking

before you I am carrying out the mission I set

for myself, I may die peacefully and content. So

I shall not mince my words about those savage

murderers.

I must pause to consider the facts for a moment.

The government itself said the attack showed

such precision and perfection that it must have

been planned by military strategists. Nothing

could have been farther from the truth! The plan

was drawn up by a group of young men, none of

whom had any military experience at all. I will

reveal their names, omitting two who are neither

dead nor in prison: Abel Santamaría, José Luis

Tasende, Renato Guitart Rosell, Pedro Miret,

Jesús Montané and myself. Half of them are dead,

and in tribute to their memory I can say that

although they were not military experts they had

enough patriotism to have given, had we not been

at such a great disadvantage, a good beating to

that entire lot of generals together, those

generals of the 10th of March who are neither

soldiers nor patriots. Much more difficult than

the planning of the attack was our organizing,

training, mobilizing and arming men under this

repressive regime with its millions of dollars

spent on espionage, bribery and information

services. Nevertheless, all this was carried out

by those men and many others like them with

incredible seriousness, discretion and

discipline. Still more praiseworthy is the fact

that they gave this task everything they had;

ultimately, their very lives.

The final mobilization of men who came to this

province from the most remote towns of the

entire island was accomplished with admirable

precision and in absolute secrecy. It is equally

true that the attack was carried out with

magnificent coordination. It began

simultaneously at 5:15 a.m. in both Bayamo and

Santiago de Cuba; and one by one, with an

exactitude of minutes and seconds prepared in

advance, the buildings surrounding the barracks

fell to our forces. Nevertheless, in the

interest of truth and even though it may detract

from our merit, I am also going to reveal for

the first time a fact that was fatal: due to a

most unfortunate error, half of our forces, and

the better armed half at that, went astray at

the entrance to the city and were not on hand to

help us at the decisive moment. Abel Santamaría,

with 21 men, had occupied the Civilian Hospital;

with him went a doctor and two of our women

comrades to attend to the wounded. Raúl Castro,

with ten men, occupied the Palace of Justice,

and it was my responsibility to attack the

barracks with the rest, 95 men. Preceded by an

advance group of eight who had forced Gate

Three, I arrived with the first group of 45 men.

It was precisely here that the battle began,

when my car ran into an outside patrol armed

with machine guns. The reserve group which had

almost all the heavy weapons (the light arms

were with the advance group), turned up the

wrong street and lost its way in an unfamiliar

city. I must clarify the fact that I do not for

a moment doubt the courage of those men; they

experienced great anguish and desperation when

they realized they were lost. Because of the

type of action it was and because the contending

forces were wearing identically colored

uniforms, it was not easy for these men to

re-establish contact with us. Many of them,

captured later on, met death with true heroism.

Everyone had instructions, first of all, to be

humane in the struggle. Never was a group of

armed men more generous to the adversary. From

the beginning we took numerous prisoners -

nearly twenty - and there was one moment when

three of our men - Ramiro Valdés, José Suárez

and Jesús Montané - managed to enter a barrack

and hold nearly fifty soldiers prisoners for a

short time. Those soldiers testified before the

Court, and without exception they all

acknowledged that we treated them with absolute

respect, that we didn't even subject them to one

scoffing remark. In line with this, I want to

give my heartfelt thanks to the Prosecutor for

one thing in the trial of my comrades: when he

made his report he was fair enough to

acknowledge as an incontestable fact that we

maintained a high spirit of chivalry throughout

the struggle.

Discipline among the soldiers was very poor.

They finally defeated us because of their

superior numbers - fifteen to one - and because

of the protection afforded them by the defenses

of the fortress. Our men were much better

marksmen, as our enemies themselves conceded.

There was a high degree of courage on both

sides.

In analyzing the reasons for our tactical

failure, apart from the regrettable error

already mentioned, I believe we made a mistake

by dividing the commando unit we had so

carefully trained. Of our best trained men and

boldest leaders, there were 27 in Bayamo, 21 at

the Civilian Hospital and 10 at the Palace of

Justice. If our forces had been distributed

differently the outcome of the battle might have

been different. The clash with the patrol

(purely accidental, since the unit might have

been at that point twenty seconds earlier or

twenty seconds later) alerted the camp, and gave

it time to mobilize. Otherwise it would have

fallen into our hands without a shot fired,

since we already controlled the guard post. On

the other hand, except for the .22 caliber

rifles, for which there were plenty of bullets,

our side was very short of ammunition. Had we

had hand grenades, the Army would not have been

able to resist us for fifteen minutes.

When I became convinced that all efforts to take

the barracks were now useless, I began to

withdraw our men in groups of eight and ten. Our

retreat was covered by six expert marksmen under

the command of Pedro Miret and Fidel Labrador;

heroically they held off the Army's advance. Our

losses in the battle had been insignificant; 95%

of our casualties came from the Army's

inhumanity after the struggle. The group at the

Civilian Hospital only had one casualty; the

rest of that group was trapped when the troops

blocked the only exit; but our youths did not

lay down their arms until their very last bullet

was gone. With them was Abel Santamaría, the

most generous, beloved and intrepid of our young

men, whose glorious resistance immortalizes him

in Cuban history. We shall see the fate they met

and how Batista sought to punish the heroism of

our youth.

We planned to continue the struggle in the

mountains in case the attack on the regiment

failed. In Siboney I was able to gather a third

of our forces; but many of these men were now

discouraged. About twenty of them decided to

surrender; later we shall see what became of

them. The rest, 18 men, with what arms and

ammunition were left, followed me into the

mountains. The terrain was completely unknown to

us. For a week we held the heights of the Gran

Piedra range and the Army occupied the

foothills. We could not come down; they didn't

risk coming up. It was not force of arms, but

hunger and thirst that ultimately overcame our

resistance. I had to divide the men into smaller

groups. Some of them managed to slip through the

Army lines; others were surrendered by Monsignor

Pérez Serantes. Finally only two comrades

remained with me - José Suárez and Oscar Alcalde.

While the three of us were totally exhausted, a

force led by Lieutenant Sarría surprised us in

our sleep at dawn. This was Saturday, August

1st. By that time the slaughter of prisoners had

ceased as a result of the people's protest. This

officer, a man of honor, saved us from being

murdered on the spot with our hands tied behind

us.

I need not deny here the stupid statements by

Ugalde Carrillo and company, who tried to stain

my name in an effort to mask their own

cowardice, incompetence, and criminality. The

facts are clear enough.

My purpose is not to bore the court with epic

narratives. All that I have said is essential

for a more precise understanding of what is yet

to come.

Let me mention two important facts that

facilitate an objective judgement of our

attitude. First: we could have taken over the

regiment simply by seizing all the high ranking

officers in their homes. This possibility was

rejected for the very humane reason that we

wished to avoid scenes of tragedy and struggle

in the presence of their families. Second: we

decided not to take any radio station over until

the Army camp was in our power. This attitude,

unusually magnanimous and considerate, spared

the citizens a great deal of bloodshed. With

only ten men I could have seized a radio station

and called the people to revolt. There is no

questioning the people's will to fight. I had a

recording of Eduardo Chibás' last message over

the CMQ radio network, and patriotic poems and

battle hymns capable of moving the least

sensitive, especially with the sounds of live

battle in their ears. But I did not want to use

them although our situation was desperate.

The regime has emphatically repeated that our

Movement did not have popular support. I have

never heard an assertion so naive, and at the

same time so full of bad faith. The regime seeks

to show submission and cowardice on the part of

the people. They all but claim that the people

support the dictatorship; they do not know how

offensive this is to the brave Orientales.

Santiago thought our attack was only a local

disturbance between two factions of soldiers;

not until many hours later did they realize what

had really happened. Who can doubt the valor,

civic pride and limitless courage of the rebel

and patriotic people of Santiago de Cuba? If

Moncada had fallen into our hands, even the

women of Santiago de Cuba would have risen in

arms. Many were the rifles loaded for our

fighters by the nurses at the Civilian Hospital.

They fought alongside us. That is something we

will never forget.

It was never our intention to engage the

soldiers of the regiment in combat. We wanted to

seize control of them and their weapons in a

surprise attack, arouse the people and call the

soldiers to abandon the odious flag of the

tyranny and to embrace the banner of freedom; to

defend the supreme interests of the nation and

not the petty interests of a small clique; to

turn their guns around and fire on the people's

enemies and not on the people, among whom are

their own sons and fathers; to unite with the

people as the brothers that they are instead of

opposing the people as the enemies the

government tries to make of them; to march

behind the only beautiful ideal worthy of

sacrificing one's life - the greatness and

happiness of one's country. To those who doubt

that many soldiers would have followed us, I

ask: What Cuban does not cherish glory? What

heart is not set aflame by the promise of

freedom?

The Navy did not fight against us, and it would

undoubtedly have come over to our side later on.

It is well known that that branch of the Armed

Forces is the least dominated by the

Dictatorship and that there is a very intense

civic conscience among its members. But, as to

the rest of the national armed forces, would

they have fought against a people in revolt? I

declare that they would not! A soldier is made

of flesh and blood; he thinks, observes, feels.

He is susceptible to the opinions, beliefs,

sympathies and antipathies of the people. If you

ask his opinion, he may tell you he cannot

express it; but that does not mean he has no

opinion. He is affected by exactly the same

problems that affect other citizens -

subsistence, rent, the education of his

children, their future, etc. Everything of this

kind is an inevitable point of contact between

him and the people and everything of this kind

relates him to the present and future situation

of the society in which he lives. It is foolish

to imagine that the salary a soldier receives

from the State - a modest enough salary at that

- should resolve the vital problems imposed on

him by his needs, duties and feelings as a

member of his community.

This brief explanation has been necessary

because it is basic to a consideration to which

few people, until now, have paid any attention -

soldiers have a deep respect for the feelings of

the majority of the people! During the Machado

regime, in the same proportion as popular

antipathy increased, the loyalty of the Army

visibly decreased. This was so true that a group

of women almost succeeded in subverting Camp

Columbia. But this is proven even more clearly

by a recent development. While Grau San Martín's

regime was able to preserve its maximum

popularity among the people, unscrupulous

ex-officers and power-hungry civilians attempted

innumerable conspiracies in the Army, although

none of them found a following in the rank and

file.

The March 10th coup took place at the moment

when the civil government's prestige had

dwindled to its lowest ebb, a circumstance of

which Batista and his clique took advantage. Why

did they not strike their blow after the first

of June? Simply because, had they waited for the

majority of the nation to express its will at

the polls, the troops would not have responded

to the conspiracy!

Consequently, a second assertion can be made:

the Army has never revolted against a regime

with a popular majority behind it. These are

historic truths, and if Batista insists on

remaining in power at all costs against the will

of the majority of Cubans, his end will be more

tragic than that of Gerardo Machado.

I have a right to express an opinion about the

Armed Forces because I defended them when

everyone else was silent. And I did this neither

as a conspirator, nor from any kind of personal

interest - for we then enjoyed full

constitutional prerogatives. I was prompted only

by humane instincts and civic duty. In those

days, the newspaper Alerta was one of the most

widely read because of its position on national

political matters. In its pages I campaigned

against the forced labor to which the soldiers

were subjected on the private estates of high

civil personages and military officers. On March

3rd, 1952 I supplied the Courts with data,

photographs, films and other proof denouncing

this state of affairs. I also pointed out in

those articles that it was elementary decency to

increase army salaries. I should like to know

who else raised his voice on that occasion to

protest against all this injustice done to the

soldiers. Certainly not Batista and company,

living well-protected on their luxurious

estates, surrounded by all kinds of security

measures, while I ran a thousand risks with

neither bodyguards nor arms.

Just as I defended the soldiers then, now - when

all others are once more silent - I tell them

that they allowed themselves to be miserably

deceived; and to the deception and shame of

March 10th they have added the disgrace, the

thousand times greater disgrace, of the fearful

and unjustifiable crimes of Santiago de Cuba.

From that time since, the uniform of the Army is

splattered with blood. And as last year I told

the people and cried out before the Courts that

soldiers were working as slaves on private

estates, today I make the bitter charge that

there are soldiers stained from head to toe with

the blood of the Cuban youths they have tortured

and slain. And I say as well that if the Army

serves the Republic, defends the nation,

respects the people and protects the citizenry

then it is only fair that the soldier should

earn at least a hundred pesos a month. But if

the soldiers slay and oppress the people, betray

the nation and defend only the interests of one

small group, then the Army deserves not a cent

of the Republic's money and Camp Columbia should

be converted into a school with ten thousand

orphans living there instead of soldiers.

I want to be just above all else, so I can't

blame all the soldiers for the shameful crimes

that stain a few evil and treacherous Army men.

But every honorable and upstanding soldier who

loves his career and his uniform is dutybound to

demand and to fight for the cleansing of this

guilt, to avenge this betrayal and to see the

guilty punished. Otherwise the soldier's uniform

will forever be a mark of infamy instead of a

source of pride.

Of course the March 10th regime had no choice

but to remove the soldiers from the private

estates. But it did so only to put them to work

as doormen, chauffeurs, servants and bodyguards

for the whole rabble of petty politicians who

make up the party of the Dictatorship. Every

fourth or fifth rank official considers himself

entitled to the services of a soldier to drive

his car and to watch over him as if he were

constantly afraid of receiving the kick in the

pants he so justly deserves.

If they had been at all interested in promoting

real reforms, why did the regime not confiscate

the estates and the millions of men like

Genovevo Pérez Dámera, who acquired their

fortunes by exploiting soldiers, driving them

like slaves and misappropriating the funds of

the Armed Forces? But no: Genovevo Pérez and

others like him no doubt still have soldiers

protecting them on their estates because the

March 10th generals, deep in their hearts,

aspire to the same future and can't allow that

kind of precedent to be set.

The 10th of March was a miserable deception, yes

... After Batista and his band of corrupt and

disreputable politicians had failed in their

electoral plan, they took advantage of the

Army's discontent and used it to climb to power

on the backs of the soldiers. And I know there

are many Army men who are disgusted because they

have been disappointed. At first their pay was

raised, but later, through deductions and

reductions of every kind, it was lowered again.

Many of the old elements, who had drifted away

from the Armed Forces, returned to the ranks and

blocked the way of young, capable and valuable

men who might otherwise have advanced. Good

soldiers have been neglected while the most

scandalous nepotism prevails. Many decent

military men are now asking themselves what need

that Armed Forces had to assume the tremendous

historical responsibility of destroying our

Constitution merely to put a group of immoral

men in power, men of bad reputation, corrupt,

politically degenerate beyond redemption, who

could never again have occupied a political post

had it not been at bayonet-point; and they

weren't even the ones with the bayonets in their

hands ...

On the other hand, the soldiers endure a worse

tyranny than the civilians. They are under

constant surveillance and not one of them enjoys

the slightest security in his job. Any

unjustified suspicion, any gossip, any intrigue,

or denunciation, is sufficient to bring

transfer, dishonorable discharge or

imprisonment. Did not Tabernilla, in a

memorandum, forbid them to talk with anyone

opposed to the government, that is to say, with

ninety-nine percent of the people? ... What a

lack of confidence! ... Not even the vestal

virgins of Rome had to abide by such a rule! As

for the much publicized little houses for

enlisted men, there aren't 300 on the whole

Island; yet with what has been spent on tanks,

guns and other weaponry every soldier might have

a place to live. Batista isn't concerned with

taking care of the Army, but that the Army take

care of him! He increases the Army's power of

oppression and killing but does not improve

living conditions for the soldiers. Triple guard

duty, constant confinement to barracks,

continuous anxiety, the enmity of the people,

uncertainty about the future - this is what has

been given to the soldier. In other words: 'Die

for the regime, soldier, give it your sweat and

blood. We shall dedicate a speech to you and

award you a posthumous promotion (when it no

longer matters) and afterwards ... we shall go

on living luxuriously, making ourselves rich.

Kill, abuse, oppress the people. When the people

get tired and all this comes to an end, you can

pay for our crimes while we go abroad and live

like kings. And if one day we return, don't you

or your children knock on the doors of our

mansions, for we shall be millionaires and

millionaires do not mingle with the poor. Kill,

soldier, oppress the people, die for the regime,

give your sweat and blood ...'

But if blind to this sad truth, a minority of

soldiers had decided to fight the people, the

people who were going to liberate them from

tyranny, victory still would have gone to the

people. The Honorable Prosecutor was very

interested in knowing our chances for success.

These chances were based on considerations of

technical, military and social order. They have

tried to establish the myth that modern arms

render the people helpless in overthrowing

tyrants. Military parades and the pompous

display of machines of war are used to

perpetuate this myth and to create a complex of

absolute impotence in the people. But no

weaponry, no violence can vanquish the people

once they are determined to win back their

rights. Both past and present are full of

examples. The most recent is the revolt in

Bolivia, where miners with dynamite sticks

smashed and defeated regular army regiments.

Fortunately, we Cubans need not look for

examples abroad. No example is as inspiring as

that of our own land. During the war of 1895

there were nearly half a million armed Spanish

soldiers in Cuba, many more than the Dictator

counts upon today to hold back a population five

times greater. The arms of the Spaniards were,

incomparably, both more up to date and more

powerful than those of our mambises. Often the

Spaniards were equipped with field artillery and

the infantry used breechloaders similar to those

still in use by the infantry of today. The

Cubans were usually armed with no more than

their machetes, for their cartridge belts were

almost always empty. There is an unforgettable

passage in the history of our War of

Independence, narrated by General Miró Argenter,

Chief of Antonio Maceo's General Staff. I

managed to bring it copied on this scrap of

paper so I wouldn't have to depend upon my

memory:

'Untrained men under the command of Pedro

Delgado, most of them equipped only with

machetes, were virtually annihilated as they

threw themselves on the solid rank of Spaniards.

It is not an exaggeration to assert that of

every fifty men, 25 were killed. Some even

attacked the Spaniards with their bare fists,

without machetes, without even knives. Searching

through the reeds by the Hondo River, we found

fifteen more dead from the Cuban party, and it

was not immediately clear what group they

belonged to, They did not appear to have

shouldered arms, their clothes were intact and

only tin drinking cups hung from their waists; a

few steps further on lay the dead horse, all its

equipment in order. We reconstructed the climax

of the tragedy. These men, following their

daring chief, Lieutenant Colonel Pedro Delgado,

had earned heroes' laurels: they had thrown

themselves against bayonets with bare hands, the

clash of metal which was heard around them was

the sound of their drinking cups banging against

the saddlehorn. Maceo was deeply moved. This man

so used to seeing death in all its forms

murmured this praise: "I had never seen anything

like this, untrained and unarmed men attacking

the Spaniards with only drinking cups for

weapons. And I called it impedimenta!"'

This is how peoples fight when they want to win

their freedom; they throw stones at airplanes

and overturn tanks!

As soon as Santiago de Cuba was in our hands we

would immediately have readied the people of

Oriente for war. Bayamo was attacked precisely

to locate our advance forces along the Cauto

River. Never forget that this province, which

has a million and a half inhabitants today, is

the most rebellious and patriotic in Cuba. It

was this province that sparked the fight for

independence for thirty years and paid the

highest price in blood, sacrifice and heroism.

In Oriente you can still breathe the air of that

glorious epic. At dawn, when the cocks crow as

if they were bugles calling soldiers to

reveille, and when the sun rises radiant over

the rugged mountains, it seems that once again

we will live the days of Yara or Baire!

I stated that the second consideration on which

we based our chances for success was one of

social order. Why were we sure of the people's

support? When we speak of the people we are not

talking about those who live in comfort, the

conservative elements of the nation, who welcome

any repressive regime, any dictatorship, any

despotism, prostrating themselves before the

masters of the moment until they grind their

foreheads into the ground. When we speak of

struggle and we mention the people we mean the

vast unredeemed masses, those to whom everyone

makes promises and who are deceived by all; we

mean the people who yearn for a better, more

dignified and more just nation; who are moved by

ancestral aspirations to justice, for they have

suffered injustice and mockery generation after

generation; those who long for great and wise

changes in all aspects of their life; people

who, to attain those changes, are ready to give

even the very last breath they have when they

believe in something or in someone, especially

when they believe in themselves. The first

condition of sincerity and good faith in any

endeavor is to do precisely what nobody else

ever does, that is, to speak with absolute

clarity, without fear. The demagogues and

professional politicians who manage to perform

the miracle of being right about everything and

of pleasing everyone are, necessarily, deceiving

everyone about everything. The revolutionaries

must proclaim their ideas courageously, define

their principles and express their intentions so

that no one is deceived, neither friend nor foe.

In terms of struggle, when we talk about people

we're talking about the six hundred thousand

Cubans without work, who want to earn their

daily bread honestly without having to emigrate

from their homeland in search of a livelihood;

the five hundred thousand farm laborers who live

in miserable shacks, who work four months of the

year and starve the rest, sharing their misery

with their children, who don't have an inch of

land to till and whose existence would move any

heart not made of stone; the four hundred

thousand industrial workers and laborers whose

retirement funds have been embezzled, whose

benefits are being taken away, whose homes are

wretched quarters, whose salaries pass from the

hands of the boss to those of the moneylender,

whose future is a pay reduction and dismissal,

whose life is endless work and whose only rest

is the tomb; the one hundred thousand small

farmers who live and die working land that is

not theirs, looking at it with the sadness of

Moses gazing at the promised land, to die

without ever owning it, who like feudal serfs

have to pay for the use of their parcel of land

by giving up a portion of its produce, who

cannot love it, improve it, beautify it nor

plant a cedar or an orange tree on it because

they never know when a sheriff will come with

the rural guard to evict them from it; the

thirty thousand teachers and professors who are

so devoted, dedicated and so necessary to the

better destiny of future generations and who are

so badly treated and paid; the twenty thousand

small business men weighed down by debts, ruined

by the crisis and harangued by a plague of

grafting and venal officials; the ten thousand

young professional people: doctors, engineers,

lawyers, veterinarians, school teachers,

dentists, pharmacists, newspapermen, painters,

sculptors, etc., who finish school with their

degrees anxious to work and full of hope, only

to find themselves at a dead end, all doors

closed to them, and where no ears hear their

clamor or supplication. These are the people,

the ones who know misfortune and, therefore, are

capable of fighting with limitless courage! To

these people whose desperate roads through life

have been paved with the bricks of betrayal and

false promises, we were not going to say: 'We

will give you ...' but rather: 'Here it is, now

fight for it with everything you have, so that

liberty and happiness may be yours!'

The five revolutionary laws that would have been

proclaimed immediately after the capture of the

Moncada Barracks and would have been broadcast

to the nation by radio must be included in the

indictment. It is possible that Colonel Chaviano

may deliberately have destroyed these documents,

but even if he has I remember them.

The first revolutionary law would have returned

power to the people and proclaimed the 1940

Constitution the Supreme Law of the State until

such time as the people should decide to modify

or change it. And in order to effect its

implementation and punish those who violated it

- there being no electoral organization to carry

this out - the revolutionary movement, as the

circumstantial incarnation of this sovereignty,

the only source of legitimate power, would have

assumed all the faculties inherent therein,

except that of modifying the Constitution

itself: in other words, it would have assumed

the legislative, executive and judicial powers.

This attitude could not be clearer nor more free

of vacillation and sterile charlatanry. A

government acclaimed by the mass of rebel people

would be vested with every power, everything

necessary in order to proceed with the effective

implementation of popular will and real justice.

From that moment, the Judicial Power - which

since March 10th had placed itself against and

outside the Constitution - would cease to exist

and we would proceed to its immediate and total

reform before it would once again assume the

power granted it by the Supreme Law of the

Republic. Without these previous measures, a

return to legality by putting its custody back

into the hands that have crippled the system so

dishonorably would constitute a fraud, a deceit,

one more betrayal.

The second revolutionary law would give non-mortgageable

and non-transferable ownership of the land to

all tenant and subtenant farmers, lessees, share

croppers and squatters who hold parcels of five

caballerías of land or less, and the State would

indemnify the former owners on the basis of the

rental which they would have received for these

parcels over a period of ten years.

The third revolutionary law would have granted

workers and employees the right to share 30% of

the profits of all the large industrial,

mercantile and mining enterprises, including the

sugar mills. The strictly agricultural

enterprises would be exempt in consideration of

other agrarian laws which would be put into

effect.

The fourth revolutionary law would have granted

all sugar planters the right to share 55% of

sugar production and a minimum quota of forty

thousand arrobas for all small tenant farmers

who have been established for three years or

more.

The fifth revolutionary law would have ordered

the confiscation of all holdings and ill-gotten

gains of those who had committed frauds during

previous regimes, as well as the holdings and

ill-gotten gains of all their legates and heirs.

To implement this, special courts with full

powers would gain access to all records of all

corporations registered or operating in this

country, in order to investigate concealed funds

of illegal origin, and to request that foreign

governments extradite persons and attach

holdings rightfully belonging to the Cuban

people. Half of the property recovered would be

used to subsidize retirement funds for workers

and the other half would be used for hospitals,

asylums and charitable organizations.

Furthermore, it was declared that the Cuban

policy in the Americas would be one of close

solidarity with the democratic peoples of this

continent, and that all those politically

persecuted by bloody tyrannies oppressing our

sister nations would find generous asylum,

brotherhood and bread in the land of Martí; not

the persecution, hunger and treason they find

today. Cuba should be the bulwark of liberty and

not a shameful link in the chain of despotism.

These laws would have been proclaimed

immediately. As soon as the upheaval ended and

prior to a detailed and far reaching study, they

would have been followed by another series of

laws and fundamental measures, such as the

Agrarian Reform, the Integral Educational

Reform, nationalization of the electric power

trust and the telephone trust, refund to the

people of the illegal and repressive rates these

companies have charged, and payment to the

treasury of all taxes brazenly evaded in the

past.

All these laws and others would be based on the

exact compliance of two essential articles of

our Constitution: one of them orders the

outlawing of large estates, indicating the

maximum area of land any one person or entity

may own for each type of agricultural

enterprise, by adopting measures which would

tend to revert the land to the Cubans. The other

categorically orders the State to use all means

at its disposal to provide employment to all

those who lack it and to ensure a decent

livelihood to each manual or intellectual

laborer. None of these laws can be called

unconstitutional. The first popularly elected

government would have to respect them, not only

because of moral obligations to the nation, but

because when people achieve something they have

yearned for throughout generations, no force in

the world is capable of taking it away again.

The problem of the land, the problem of

industrialization, the problem of housing, the

problem of unemployment, the problem of

education and the problem of the people's

health: these are the six problems we would take

immediate steps to solve, along with restoration

of civil liberties and political democracy.

This exposition may seem cold and theoretical if

one does not know the shocking and tragic

conditions of the country with regard to these

six problems, along with the most humiliating

political oppression.

Eighty-five per cent of the small farmers in

Cuba pay rent and live under constant threat of

being evicted from the land they till. More than

half of our most productive land is in the hands

of foreigners. In Oriente, the largest province,

the lands of the United Fruit Company and the

West Indian Company link the northern and

southern coasts. There are two hundred thousand

peasant families who do not have a single acre

of land to till to provide food for their

starving children. On the other hand, nearly

three hundred thousand caballerías of cultivable

land owned by powerful interests remain

uncultivated. If Cuba is above all an

agricultural State, if its population is largely

rural, if the city depends on these rural areas,

if the people from our countryside won our war

of independence, if our nation's greatness and

prosperity depend on a healthy and vigorous

rural population that loves the land and knows

how to work it, if this population depends on a

State that protects and guides it, then how can

the present state of affairs be allowed to

continue?

Except for a few food, lumber and textile

industries, Cuba continues to be primarily a

producer of raw materials. We export sugar to

import candy, we export hides to import shoes,

we export iron to import plows ... Everyone

agrees with the urgent need to industrialize the

nation, that we need steel industries, paper and

chemical industries, that we must improve our

cattle and grain production, the technology and

processing in our food industry in order to

defend ourselves against the ruinous competition

from Europe in cheese products, condensed milk,

liquors and edible oils, and the United States

in canned goods; that we need cargo ships; that

tourism should be an enormous source of revenue.

But the capitalists insist that the workers

remain under the yoke. The State sits back with

its arms crossed and industrialization can wait

forever.

Just as serious or even worse is the housing

problem. There are two hundred thousand huts and

hovels in Cuba; four hundred thousand families

in the countryside and in the cities live

cramped in huts and tenements without even the

minimum sanitary requirements; two million two

hundred thousand of our urban population pay

rents which absorb between one fifth and one

third of their incomes; and two million eight

hundred thousand of our rural and suburban

population lack electricity. We have the same

situation here: if the State proposes the

lowering of rents, landlords threaten to freeze

all construction; if the State does not

interfere, construction goes on so long as

landlords get high rents; otherwise they would

not lay a single brick even though the rest of

the population had to live totally exposed to

the elements. The utilities monopoly is no

better; they extend lines as far as it is

profitable and beyond that point they don't care

if people have to live in darkness for the rest

of their lives. The State sits back with its

arms crossed and the people have neither homes

nor electricity.

Our educational system is perfectly compatible

with everything I've just mentioned. Where the

peasant doesn't own the land, what need is there

for agricultural schools? Where there is no

industry, what need is there for technical or

vocational schools? Everything follows the same

absurd logic; if we don't have one thing we

can't have the other. In any small European

country there are more than 200 technological

and vocational schools; in Cuba only six such

schools exist, and their graduates have no jobs

for their skills. The little rural schoolhouses

are attended by a mere half of the school age

children - barefooted, half-naked and

undernourished - and frequently the teacher must

buy necessary school materials from his own

salary. Is this the way to make a nation great?

Only death can liberate one from so much misery.

In this respect, however, the State is most

helpful - in providing early death for the

people. Ninety per cent of the children in the

countryside are consumed by parasites which

filter through their bare feet from the ground

they walk on. Society is moved to compassion

when it hears of the kidnapping or murder of one

child, but it is indifferent to the mass murder

of so many thousands of children who die every

year from lack of facilities, agonizing with

pain. Their innocent eyes, death already shining

in them, seem to look into some vague infinity

as if entreating forgiveness for human

selfishness, as if asking God to stay His wrath.

And when the head of a family works only four

months a year, with what can he purchase

clothing and medicine for his children? They

will grow up with rickets, with not a single

good tooth in their mouths by the time they

reach thirty; they will have heard ten million

speeches and will finally die of misery and

deception. Public hospitals, which are always

full, accept only patients recommended by some

powerful politician who, in return, demands the

votes of the unfortunate one and his family so

that Cuba may continue forever in the same or

worse condition.

With this background, is it not understandable

that from May to December over a million persons

are jobless and that Cuba, with a population of

five and a half million, has a greater number of

unemployed than France or Italy with a

population of forty million each?

When you try a defendant for robbery, Honorable

Judges, do you ask him how long he has been

unemployed? Do you ask him how many children he

has, which days of the week he ate and which he

didn't, do you investigate his social context at

all? You just send him to jail without further

thought. But those who burn warehouses and

stores to collect insurance do not go to jail,

even though a few human beings may have gone up

in flames. The insured have money to hire

lawyers and bribe judges. You imprison the poor

wretch who steals because he is hungry; but none

of the hundreds who steal millions from the

Government has ever spent a night in jail. You

dine with them at the end of the year in some

elegant club and they enjoy your respect. In

Cuba, when a government official becomes a

millionaire overnight and enters the fraternity

of the rich, he could very well be greeted with

the words of that opulent character out of

Balzac - Taillefer - who in his toast to the

young heir to an enormous fortune, said:

'Gentlemen, let us drink to the power of gold!

Mr. Valentine, a millionaire six times over, has

just ascended the throne. He is king, can do

everything, is above everyone, as all the rich

are. Henceforth, equality before the law,

established by the Constitution, will be a myth

for him; for he will not be subject to laws: the

laws will be subject to him. There are no courts

nor are there sentences for millionaires.'

The nation's future, the solutions to its

problems, cannot continue to depend on the

selfish interests of a dozen big businessmen nor

on the cold calculations of profits that ten or

twelve magnates draw up in their air-conditioned

offices. The country cannot continue begging on

its knees for miracles from a few golden calves,

like the Biblical one destroyed by the prophet's

fury. Golden calves cannot perform miracles of

any kind. The problems of the Republic can be

solved only if we dedicate ourselves to fight

for it with the same energy, honesty and

patriotism our liberators had when they founded

it. Statesmen like Carlos Saladrigas, whose

statesmanship consists of preserving the statu

quo and mouthing phrases like 'absolute freedom

of enterprise,' 'guarantees to investment

capital' and 'law of supply and demand,' will

not solve these problems. Those ministers can

chat away in a Fifth Avenue mansion until not

even the dust of the bones of those whose

problems require immediate solution remains. In

this present-day world, social problems are not

solved by spontaneous generation.

A revolutionary government backed by the people

and with the respect of the nation, after

cleansing the different institutions of all

venal and corrupt officials, would proceed

immediately to the country's industrialization,

mobilizing all inactive capital, currently

estimated at about 1.5 billion pesos, through

the National Bank and the Agricultural and

Industrial Development Bank, and submitting this

mammoth task to experts and men of absolute

competence totally removed from all political

machines for study, direction, planning and

realization.

After settling the one hundred thousand small

farmers as owners on the land which they

previously rented, a revolutionary government

would immediately proceed to settle the land

problem. First, as set forth in the

Constitution, it would establish the maximum

amount of land to be held by each type of

agricultural enterprise and would acquire the

excess acreage by expropriation, recovery of

swampland, planting of large nurseries, and

reserving of zones for reforestation. Secondly,

it would distribute the remaining land among

peasant families with priority given to the

larger ones, and would promote agricultural

cooperatives for communal use of expensive

equipment, freezing plants and unified

professional technical management of farming and

cattle raising. Finally, it would provide

resources, equipment, protection and useful

guidance to the peasants.

A revolutionary government would solve the

housing problem by cutting all rents in half, by

providing tax exemptions on homes inhabited by

the owners; by tripling taxes on rented homes;

by tearing down hovels and replacing them with

modern apartment buildings; and by financing

housing all over the island on a scale

heretofore unheard of, with the criterion that,

just as each rural family should possess its own

tract of land, each city family should own its

own house or apartment. There is plenty of

building material and more than enough manpower

to make a decent home for every Cuban. But if we

continue to wait for the golden calf, a thousand

years will have gone by and the problem will

remain the same. On the other hand, today

possibilities of taking electricity to the most

isolated areas on the island are greater than

ever. The use of nuclear energy in this field is

now a reality and will greatly reduce the cost

of producing electricity.

With these three projects and reforms, the

problem of unemployment would automatically

disappear and the task of improving public

health and fighting against disease would become

much less difficult.

This is page 1 of

2. Go to

page 2 of this speech.

page 2 of this speech.

More History

|

|