|

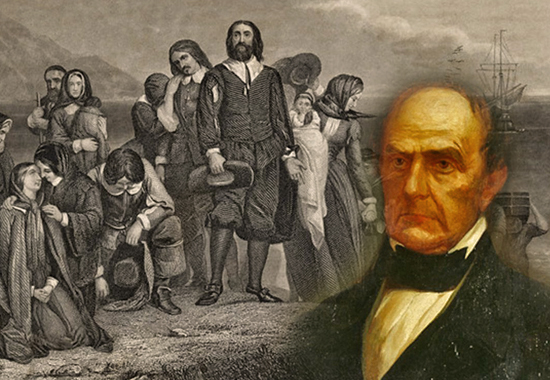

DANIEL WEBSTER COMMEMORATING THE

PILGRIM'S LANDING OF 1620

The Plymouth Oration

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster.

Daniel Webster.

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

It follows the full text transcript of

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration, delivered at

Plymouth, Massachusetts - December 22, 1820.

This is page 1 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 2. Go to

page 2. Go to

page 3.

page 3.

|

Let us rejoice

that we behold this day. |

Let us be thankful

that we have lived to see the bright and happy

breaking of the auspicious morn, which commences

the third century of the history of New England.

Auspicious, indeed,—bringing a happiness beyond

the common allotment of Providence to men,—full

of present joy, and gilding with bright beams

the prospect of futurity, is the dawn that

awakens us to the commemoration of the landing

of the Pilgrims.

Living at an epoch which naturally marks the

progress of the history of our native land, we

have come hither to celebrate the great event

with which that history commenced. For ever

honored be this, the place of our fathers'

refuge! For ever remembered the day which saw

them, weary and distressed, broken in every

thing but spirit, poor in all but faith and

courage, at last secure from the dangers of

wintry seas, and impressing this shore with the

first footsteps of civilized man!

It is a noble faculty of our nature which

enables us to connect our thoughts, our

sympathies, and our happiness with what is

distant in place or time; and, looking before

and after, to hold communion at once with our

ancestors and our posterity. Human and mortal

although we are, we are nevertheless not mere

insulated beings, without relation to the past

or the future. Neither the point of time, nor

the spot of earth, in which we physically live,

bounds our rational and intellectual enjoyments.

We live in the past by a knowledge of its

history; and in the future, by hope and

anticipation. By ascending to an association

with our ancestors; by contemplating their

example and studying their character; by

partaking their sentiments, and imbibing their

spirit; by accompanying them in their toils, by

sympathizing in their sufferings, and rejoicing

in their successes and their triumphs; we seem

to belong to their age, and to mingle our own

existence with theirs. We become their

contemporaries, live the lives which they lived,

endure what they endured, and partake in the

rewards which they enjoyed. And in like manner,

by running along the line of future time, by

contemplating the probable fortunes of those who

are coming after us, by attempting something

which may promote their happiness, and leave

some not dishonorable memorial of ourselves for

their regard, when we shall sleep with the

fathers, we protract our own earthly being, and

seem to crowd whatever is future, as well as all

that is past, into the narrow compass of our

earthly existence. As it is not a vain and

false, but an exalted and religious imagination,

which leads us to raise our thoughts from the

orb, which, amidst this universe of worlds, the

Creator has given us to inhabit, and to send

them with something of the feeling which nature

prompts, and teaches to be proper among children

of the same Eternal Parent, to the contemplation

of the myriads of fellow-beings with which his

goodness has peopled the infinite of space; so

neither is it false or vain to consider

ourselves as interested and connected with our

whole race, through all time; allied to our

ancestors; allied to our posterity; closely

compacted on all sides with others; ourselves

being but links in the great chain of being,

which begins with the origin of our race, runs

onward through its successive generations,

binding together the past, the present, and the

future, and terminating at last, with the

consummation of all things earthly, at the

throne of God.

There may be, and there often is, indeed, a

regard for ancestry, which nourishes only a weak

pride; as there is also a care for posterity,

which only disguises an habitual avarice, or

hides the workings of a low and groveling

vanity. But there is also a moral and

philosophical respect for our ancestors, which

elevates the character and improves the heart.

Next to the sense of religious duty and moral

feeling, I hardly know what should bear with

stronger obligation on a liberal and enlightened

mind, than a consciousness of alliance with

excellence which is departed; and a

consciousness, too, that in its acts and

conduct, and even in its sentiments and

thoughts, it may be actively operating on the

happiness of those who come after it. Poetry is

found to have few stronger conceptions, by which

it would affect or overwhelm the mind, than

those in which it presents the moving and

speaking image of the departed dead to the

senses of the living. This belongs to poetry,

only because it is congenial to our nature.

Poetry is, in this respect, but the handmaid of

true philosophy and morality; it deals with us

as human beings, naturally reverencing those

whose visible connection with this state of

existence is severed, and who may yet exercise

we know not what sympathy with ourselves; and

when it carries us forward, also, and shows us

the long continued result of all the good we do,

in the prosperity of those who follow us, till

it bears us from ourselves, and absorbs us in an

intense interest for what shall happen to the

generations after us, it speaks only in the

language of our nature, and affects us with

sentiments which belong to us as human beings.

Standing in this relation to our ancestors and

our posterity, we are assembled on this

memorable spot, to perform the duties which that

relation and the present occasion impose upon

us. We have come to this Rock, to record here

our homage for our Pilgrim Fathers; our sympathy

in their sufferings; our gratitude for their

labors; our admiration of their virtues; our

veneration for their piety; and our attachment

to those principles of civil and religious

liberty, which they encountered the dangers of

the ocean, the storms of heaven, the violence of

savages, disease, exile, and famine, to enjoy

and to establish. And we would leave here, also,

for the generations which are rising up rapidly

to fill our places, some proof that we have

endeavored to transmit the great inheritance

unimpaired; that in our estimate of public

principles and private virtue, in our veneration

of religion and piety, in our devotion to civil

and religious liberty, in our regard for

whatever advances human knowledge or improves

human happiness, we are not altogether unworthy

of our origin.

There is a local feeling connected with this

occasion, too strong to be resisted; a sort of

genius of the place, which inspires and awes us.

We feel that we are on the spot where the first

scene of our history was laid; where the hearths

and altars of New England were first placed;

where Christianity, and civilization, and

letters made their first lodgment, in a vast

extent of country, covered with a wilderness,

and peopled by roving barbarians. We are here,

at the season of the year at which the event

took place. The imagination irresistibly and

rapidly draws around us the principal features

and the leading characters in the original

scene. We cast our eyes abroad on the ocean, and

we see where the little bark, with the

interesting group upon its deck, made its slow

progress to the shore. We look around us, and

behold the hills and promontories where the

anxious eyes of our fathers first saw the places

of habitation and of rest. We feel the cold

which benumbed, and listen to the winds which

pierced them. Beneath us is the Rock, on which

New England received the feet of the Pilgrims.

We seem even to behold them, as they struggle

with the elements, and, with toilsome efforts,

gain the shore. We listen to the chiefs in

council; we see the unexampled exhibition of

female fortitude and resignation; we hear the

whisperings of youthful impatience, and we see,

what a painter of our own has also represented

by his pencil, chilled and shivering childhood,

houseless, but for a mother's arms, couchless,

but for a mother's breast, till our own blood

almost freezes. The mild dignity of Carver and

of Bradford; the decisive and soldier-like air

and manner of Standish; the devout Brewster; the

enterprising Allerton; the general firmness and

thoughtfulness of the whole band; their

conscious joy for dangers escaped; their deep

solicitude about dangers to come; their trust in

Heaven; their high religious faith, full of

confidence and anticipation; all of these seem

to belong to this place, and to be present upon

this occasion, to fill us with reverence and

admiration.

The settlement of New England by the colony

which landed here on the twenty-second of

December, sixteen hundred and twenty, although

not the first European establishment in what now

constitutes the United States, was yet so

peculiar in its causes and character, and has

been followed and must still be followed by such

consequences, as to give it a high claim to

lasting commemoration. On these causes and

consequences, more than on its immediately

attendant circumstances, its importance, as an

historical event, depends. Great actions and

striking occurrences, having excited a temporary

admiration, often pass away and are forgotten,

because they leave no lasting results, affecting

the prosperity and happiness of communities.

Such is frequently the fortune of the most

brilliant military achievements. Of the ten

thousand battles which have been fought, of all

the fields fertilized with carnage, of the

banners which have been bathed in blood, of the

warriors who have hoped that they had risen from

the field of conquest to a glory as bright and

as durable as the stars, how few that continue

long to interest mankind! The victory of

yesterday is reversed by the defeat of to-day;

the star of military glory, rising like a

meteor, like a meteor has fallen; disgrace and

disaster hang on the heels of conquest and

renown; victor and vanquished presently pass

away to oblivion, and the world goes on in its

course, with the loss only of so many lives and

so much treasure.

But if this be frequently, or generally, the

fortune of military achievements, it is not

always so. There are enterprises, military as

well as civil, which sometimes check the current

of events, give a new turn to human affairs, and

transmit their consequences through ages. We see

their importance in their results, and call them

great, because great things follow. There have

been battles which have fixed the fate of

nations. These come down to us in history with a

solid and permanent interest, not created by a

display of glittering armor, the rush of adverse

battalions, the sinking and rising of pennons,

the flight, the pursuit, and the victory; but by

their effect in advancing or retarding human

knowledge, in overthrowing or establishing

despotism, in extending or destroying human

happiness. When the traveler pauses on the plain

of Marathon, what are the emotions which most

strongly agitate his breast? What is that

glorious recollection, which thrills through his

frame, and suffuses his eyes? Not, I imagine,

that Grecian skill and Grecian valor were here

most signally displayed; but that Greece herself

was saved. It is because to this spot, and to

the event which has rendered it immortal, he

refers all the succeeding glories of the

republic. It is because, if that day had gone

otherwise, Greece had perished. It is because he

perceives that her philosophers and orators, her

poets and painters, her sculptors and

architects, her governments and free

institutions, point backward to Marathon, and

that their future existence seems to have been

suspended on the contingency, whether the

Persian or the Grecian banner should wave

victorious in the beams of that day's setting

sun. And, as his imagination kindles at the

retrospect, he is transported back to the

interesting moment; he counts the fearful odds

of the contending hosts; his interest for the

result overwhelms him; he trembles, as if it

were still uncertain, and seems to doubt whether

he may consider Socrates and Plato, Demosthenes,

Sophocles, and Phidias, as secure, yet, to

himself and to the world.

"If we conquer," said the Athenian commander on

the approach of that decisive day, "if we

conquer, we shall make Athens the greatest city

of Greece."[6] A prophecy how well fulfilled!

"If God prosper us," might have been the more

appropriate language of our fathers, when they

landed upon this Rock, "if God prosper us, we

shall here begin a work which shall last for

ages; we shall plant here a new society, in the

principles of the fullest liberty and the purest

religion; we shall subdue this wilderness which

is before us; we shall fill this region of the

great continent, which stretches almost from

pole to pole, with civilization and

Christianity; the temples of the true God shall

rise, where now ascends the smoke of idolatrous

sacrifice; fields and gardens, the flowers of

summer, and the waving and golden harvest of

autumn, shall spread over a thousand hills, and

stretch along a thousand valleys, never yet,

since the creation, reclaimed to the use of

civilized man. We shall whiten this coast with

the canvas of a prosperous commerce; we shall

stud the long and winding shore with a hundred

cities. That which we sow in weakness shall be

raised in strength. From our sincere, but

houseless worship, there shall spring splendid

temples to record God's goodness; from the

simplicity of our social union, there shall

arise wise and politic constitutions of

government, full of the liberty which we

ourselves bring and breathe; from our zeal for

learning, institutions shall spring which shall

scatter the light of knowledge throughout the

land, and, in time, paying back where they have

borrowed, shall contribute their part to the

great aggregate of human knowledge; and our

descendants, through all generations, shall look

back to this spot, and to this hour, with

unabated affection and regard."

A brief remembrance of the causes which led to

the settlement of this place; some account of

the peculiarities and characteristic qualities

of that settlement, as distinguished from other

instances of colonization; a short notice of the

progress of New England in the great interests

of society, during the century which is now

elapsed; with a few observations on the

principles upon which society and government are

established in this country; comprise all that

can be attempted, and much more than can be

satisfactorily performed, on the present

occasion.

Of the motives which influenced the first

settlers to a voluntary exile, induced them to

relinquish their native country, and to seek an

asylum in this then unexplored wilderness, the

first and principal, no doubt, were connected

with religion. They sought to enjoy a higher

degree of religious freedom, and what they

esteemed a purer form of religious worship, than

was allowed to their choice, or presented to

their imitation, in the Old World. The love of

religious liberty is a stronger sentiment, when

fully excited, than an attachment to civil or

political freedom. That freedom which the

conscience demands, and which men feel bound by

their hope of salvation to contend for, can

hardly fail to be attained. Conscience, in the

cause of religion and the worship of the Deity,

prepares the mind to act and to suffer beyond

almost all other causes. It sometimes gives an

impulse so irresistible, that no fetters of

power or of opinion can withstand it. History

instructs us that this love of religious

liberty, a compound sentiment in the breast of

man, made up of the clearest sense of right and

the highest conviction of duty, is able to look

the sternest despotism in the face, and, with

means apparently most inadequate, to shake

principalities and powers. There is a boldness,

a spirit of daring, in religious reformers, not

to be measured by the general rules which

control men's purposes and actions. If the hand

of power be laid upon it, this only seems to

augment its force and its elasticity, and to

cause its action to be more formidable and

violent. Human invention has devised nothing,

human power has compassed nothing, that can

forcibly restrain it, when it breaks forth.

Nothing can stop it, but to give way to it;

nothing can check it, but indulgence. It loses

its power only when it has gained its object.

The principle of toleration, to which the world

has come so slowly, is at once the most just and

the most wise of all principles. Even when

religious feeling takes a character of

extravagance and enthusiasm, and seems to

threaten the order of society and shake the

columns of the social edifice, its principal

danger is in its restraint. If it be allowed

indulgence and expansion, like the elemental

fires, it only agitates, and perhaps purifies,

the atmosphere; while its efforts to throw off

restraint would burst the world asunder.

It is certain, that, although many of them were

republicans in principle, we have no evidence

that our New England ancestors would have

emigrated, as they did, from their own native

country, would have become wanderers in Europe,

and finally would have undertaken the

establishment of a colony here, merely from

their dislike of the political systems of

Europe. They fled not so much from the civil

government, as from the hierarchy, and the laws

which enforced conformity to the church

establishment. Mr. Robinson had left England as

early as 1608, on account of the persecutions

for non-conformity, and had retired to Holland.

He left England from no disappointed ambition in

affairs of state, from no regrets at the want of

preferment in the church, nor from any motive of

distinction or of gain. Uniformity in matters of

religion was pressed with such extreme rigor,

that a voluntary exile seemed the most eligible

mode of escaping from the penalties of

non-compliance. The accession of Elizabeth had,

it is true, quenched the fires of Smithfield,

and put an end to the easy acquisition of the

crown of martyrdom. Her long reign had

established the Reformation, but toleration was

a virtue beyond her conception, and beyond the

age. She left no example of it to her successor;

and he was not of a character which rendered a

sentiment either so wise or so liberal would

originate with him. At the present period it

seems incredible that the learned, accomplished,

unassuming, and inoffensive Robinson should

neither be tolerated in his peaceable mode of

worship in his own country, nor suffered quietly

to depart from it. Yet such was the fact. He

left his country by stealth, that he might

elsewhere enjoy those rights which ought to

belong to men in all countries. The departure of

the Pilgrims for Holland is deeply interesting,

from its circumstances, and also as it marks the

character of the times, independently of its

connection with names now incorporated with the

history of empire. The embarkation was intended

to be made in such a manner that it might escape

the notice of the officers of government. Great

pains had been taken to secure boats, which

should come undiscovered to the shore, and

receive the fugitives; and frequent

disappointments had been experienced in this

respect.

At length the appointed time came, bringing with

it unusual severity of cold and rain. An

unfrequented and barren heath, on the shores of

Lincolnshire, was the selected spot, where the

feet of the Pilgrims were to tread, for the last

time, the land of their fathers. The vessel

which was to receive them did not come until the

next day, and in the mean time the little band

was collected, and men and women and children

and baggage were crowded together, in melancholy

and distressed confusion. The sea was rough, and

the women and children were already sick, from

their passage down the river to the place of

embarkation on the sea. At length the wished-for

boat silently and fearfully approaches the

shore, and men and women and children, shaking

with fear and with cold, as many as the small

vessel could bear, venture off on a dangerous

sea. Immediately the advance of horses is heard

from behind, armed men appear, and those not yet

embarked are seized and taken into custody. In

the hurry of the moment, the first parties had

been sent on board without any attempt to keep

members of the same family together, and on

account of the appearance of the horsemen, the

boat never returned for the residue. Those who

had got away, and those who had not, were in

equal distress. A storm, of great violence and

long duration, arose at sea, which not only

protracted the voyage, rendered distressing by

the want of all those accommodations which the

interruption of the embarkation had occasioned,

but also forced the vessel out of her course,

and menaced immediate shipwreck; while those on

shore, when they were dismissed from the custody

of the officers of justice, having no longer

homes or houses to retire to, and their friends

and protectors being already gone, became

objects of necessary charity, as well as of deep

commiseration.

As this scene passes before us, we can hardly

forbear asking whether this be a band of

malefactors and felons flying from justice. What

are their crimes, that they hide themselves in

darkness? To what punishment are they exposed,

that, to avoid it, men, and women, and children,

thus encounter the surf of the North Sea and the

terrors of a night storm? What induces this

armed pursuit, and this arrest of fugitives, of

all ages and both sexes? Truth does not allow us

to answer these inquiries in a manner that does

credit to the wisdom or the justice of the

times. This was not the flight of guilt, but of

virtue. It was an humble and peaceable religion,

flying from causeless oppression. It was

conscience, attempting to escape from the

arbitrary rule of the Stuarts. It was Robinson

and Brewster, leading off their little band from

their native soil, at first to find shelter on

the shore of the neighboring continent, but

ultimately to come hither; and having surmounted

all difficulties and braved a thousand dangers,

to find here a place of refuge and of rest.

Thanks be to God, that this spot was honored as

the asylum of religious liberty! May its

standard, reared here, remain for ever! May it

rise up as high as heaven, till its banner shall

fan the air of both continents, and wave as a

glorious ensign of peace and security to the

nations!

The peculiar character, condition, and

circumstances of the colonies which introduced

civilization and an English race into New

England, afford a most interesting and extensive

topic of discussion. On these, much of our

subsequent character and fortune has depended.

Their influence has essentially affected our

whole history, through the two centuries which

have elapsed; and as they have become intimately

connected with government, laws, and property,

as well as with our opinions on the subjects of

religion and civil liberty, that influence is

likely to continue to be felt through the

centuries which shall succeed. Emigration from

one region to another, and the emission of

colonies to people countries more or less

distant from the residence of the parent stock,

are common incidents in the history of mankind;

but it has not often, perhaps never, happened,

that the establishment of colonies should be

attempted under circumstances, however beset

with present difficulties and dangers, yet so

favorable to ultimate success, and so conducive

to magnificent results, as those which attended

the first settlements on this part of the

American continent. In other instances,

emigration has proceeded from a less exalted

purpose, in periods of less general

intelligence, or more without plan and by

accident; or under circumstances, physical and

moral, less favorable to the expectation of

laying a foundation for great public prosperity

and future empire.

A great resemblance exists, obviously, between

all the English colonies established within the

present limits of the United States; but the

occasion attracts our attention more immediately

to those which took possession of New England,

and the peculiarities of these furnish a strong

contrast with most other instances of

colonization.

Among the ancient nations, the Greeks, no doubt,

sent forth from their territories the greatest

number of colonies. So numerous, indeed, were

they, and so great the extent of space over

which they were spread, that the parent country

fondly and naturally persuaded herself, that by

means of them she had laid a sure foundation for

the universal civilization of the world. These

establishments, from obvious causes, were most

numerous in places most contiguous; yet they

were found on the coasts of France, on the

shores of the Euxine Sea, in Africa, and even,

as is alleged, on the borders of India. These

emigrations appear to have been sometimes

voluntary and sometimes compulsory; arising from

the spontaneous enterprise of individuals, or

the order and regulation of government. It was a

common opinion with ancient writers, that they

were undertaken in religious obedience to the

commands of oracles, and it is probable that

impressions of this sort might have had more or

less influence; but it is probable, also, that

on these occasions the oracles did not speak a

language dissonant from the views and purposes

of the state.

Political science among the Greeks seems never

to have extended to the comprehension of a

system, which should be adequate to the

government of a great nation upon principles of

liberty. They were accustomed only to the

contemplation of small republics, and were led

to consider an augmented population as

incompatible with free institutions. The desire

of a remedy for this supposed evil, and the wish

to establish marts for trade, led the

governments often to undertake the establishment

of colonies as an affair of state expediency.

Colonization and commerce, indeed, would

naturally become objects of interest to an

ingenious and enterprising people, inhabiting a

territory closely circumscribed in its limits,

and in no small part mountainous and sterile;

while the islands of the adjacent seas, and the

promontories and coasts of the neighboring

continents, by their mere proximity, strongly

solicited the excited spirit of emigration. Such

was this proximity, in many instances, that the

new settlements appeared rather to be the mere

extension of population over contiguous

territory, than the establishment of distant

colonies. In proportion as they were near to the

parent state, they would be under its authority,

and partake of its fortunes. The colony at

Marseilles might perceive lightly, or not at

all, the sway of Phocis; while the islands in

the Aegean Sea could hardly attain to

independence of their Athenian origin. Many of

these establishments took place at an early age;

and if there were defects in the governments of

the parent states, the colonists did not possess

philosophy or experience sufficient to correct

such evils in their own institutions, even if

they had not been, by other causes, deprived of

the power. An immediate necessity, connected

with the support of life, was the main and

direct inducement to these undertakings, and

there could hardly exist more than the hope of a

successful imitation of institutions with which

they were already acquainted, and of holding an

equality with their neighbors in the course of

improvement. The laws and customs, both

political and municipal, as well as the

religious worship of the parent city, were

transferred to the colony; and the parent city

herself, with all such of her colonies as were

not too far remote for frequent intercourse and

common sentiments, would appear like a family of

cities, more or less dependent, and more or less

connected. We know how imperfect this system

was, as a system of general politics, and what

scope it gave to those mutual dissensions and

conflicts which proved so fatal to Greece.

But it is more pertinent to our present purpose

to observe, that nothing existed in the

character of Grecian emigrations, or in the

spirit and intelligence of the emigrants, likely

to give a new and important direction to human

affairs, or a new impulse to the human mind.

Their motives were not high enough, their views

were not sufficiently large and prospective.

They went not forth, like our ancestors, to

erect systems of more perfect civil liberty, or

to enjoy a higher degree of religious freedom.

Above all, there was nothing in the religion and

learning of the age, that could either inspire

high purposes, or give the ability to execute

them. Whatever restraints on civil liberty, or

whatever abuses in religious worship, existed at

the time of our fathers' emigration, yet even

then all was light in the moral and mental

world, in comparison with its condition in most

periods of the ancient states. The settlement of

a new continent, in an age of progressive

knowledge and improvement, could not but do more

than merely enlarge the natural boundaries of

the habitable world. It could not but do much

more even than extend commerce and increase

wealth among the human race. We see how this

event has acted, how it must have acted, and

wonder only why it did not act sooner, in the

production of moral effects, on the state of

human knowledge, the general tone of human

sentiments, and the prospects of human

happiness. It gave to civilized man not only a

new continent to be inhabited and cultivated,

and new seas to be explored; but it gave him

also a new range for his thoughts, new objects

for curiosity, and new excitements to knowledge

and improvement.

Roman colonization resembled, far less than that

of the Greeks, the original settlements of this

country. Power and dominion were the objects of

Rome, even in her colonial establishments. Her

whole exterior aspect was for centuries hostile

and terrific. She grasped at dominion, from

India to Britain, and her measures of

colonization partook of the character of her

general system. Her policy was military, because

her objects were power, ascendency, and

subjugation. Detachments of emigrants from Rome

incorporated themselves with, and governed, the

original inhabitants of conquered countries. She

sent citizens where she had first sent soldiers;

her law followed her sword. Her colonies were a

sort of military establishment; so many advanced

posts in the career of her dominion. A governor

from Rome ruled the new colony with absolute

sway, and often with unbounded rapacity. In

Sicily, in Gaul, in Spain, and in Asia, the

power of Rome prevailed, not nominally only, but

really and effectually. Those who immediately

exercised it were Roman; the tone and tendency

of its administration, Roman. Rome herself

continued to be the heart and centre of the

great system which she had established.

Extortion and rapacity, finding a wide and often

rich field of action in the provinces, looked

nevertheless to the banks of the Tiber, as the

scene in which their ill-gotten treasures should

be displayed; or, if a spirit of more honest

acquisition prevailed, the object, nevertheless,

was ultimate enjoyment in Rome itself. If our

own history and our own times did not

sufficiently expose the inherent and incurable

evils of provincial government, we might see

them portrayed, to our amazement, in the

desolated and ruined provinces of the Roman

empire. We might hear them, in a voice that

terrifies us, in those strains of complaint and

accusation, which the advocates of the provinces

poured forth in the Roman Forum:

"Quas res luxuries

in flagitiis, crudelitas in suppliciis, avaritia

in rapinis, superbia in contumeliis, efficere

potuisset, eas omnes sese pertulisse."

As was to be expected, the Roman Provinces

partook of the fortunes, as well as of the

sentiments and general character, of the seat of

empire. They lived together with her, they

flourished with her, and fell with her. The

branches were lopped away even before the vast

and venerable trunk itself fell prostrate to the

earth. Nothing had proceeded from her which

could support itself, and bear up the name of

its origin, when her own sustaining arm should

be enfeebled or withdrawn. It was not given to

Rome to see, either at her zenith or in her

decline, a child of her own, distant, indeed,

and independent of her control, yet speaking her

language and inheriting her blood, springing

forward to a competition with her own power, and

a comparison with her own great renown. She saw

not a vast region of the earth peopled from her

stock, full of states and political communities,

improving upon the models of her institutions,

and breathing in fuller measure the spirit which

she had breathed in the best periods of her

existence; enjoying and extending her arts and

her literature; rising rapidly from political

childhood to manly strength and independence;

her offspring, yet now her equal; unconnected

with the causes which might affect the duration

of her own power and greatness; of common

origin, but not linked to a common fate; giving

ample pledge, that her name should not be

forgotten, that her language should not cease to

be used among men; that whatsoever she had done

for human knowledge and human happiness should

be treasured up and preserved; that the record

of her existence and her achievements should not

be obscured, although, in the inscrutable

purposes of Providence, it might be her destiny

to fall from opulence and splendor; although the

time might come, when darkness should settle on

all her hills; when foreign or domestic violence

should overturn her altars and her temples; when

ignorance and despotism should fill the places

where Laws, and Arts, and Liberty had

flourished; when the feet of barbarism should

trample on the tombs of her consuls, and the

walls of her senate-house and forum echo only to

the voice of savage triumph. She saw not this

glorious vision, to inspire and fortify her

against the possible decay or downfall of her

power. Happy are they who in our day may behold

it, if they shall contemplate it with the

sentiments which it ought to inspire!

The New England Colonies differ quite as widely

from the Asiatic establishments of the modern

European nations, as from the models of the

ancient states. The sole object of those

establishments was originally trade; although we

have seen, in one of them, the anomaly of a mere

trading company attaining a political character,

disbursing revenues, and maintaining armies and

fortresses, until it has extended its control

over seventy millions of people. Differing from

these, and still more from the New England and

North American Colonies, are the European

settlements in the West India Islands. It is not

strange, that, when men's minds were turned to

the settlement of America, different objects

should be proposed by those who emigrated to the

different regions of so vast a country. Climate,

soil, and condition were not all equally

favorable to all pursuits. In the West Indies,

the purpose of those who went thither was to

engage in that species of agriculture, suited to

the soil and climate, which seems to bear more

resemblance to commerce than to the hard and

plain tillage of New England. The great staples

of these countries, being partly an agricultural

and partly a manufactured product, and not being

of the necessaries of life, become the object of

calculation, with respect to a profitable

investment of capital, like any other enterprise

of trade or manufacture. The more especially,

as, requiring, by necessity or habit, slave

labor for their production, the capital

necessary to carry on the work of this

production is very considerable. The West Indies

are resorted to, therefore, rather for the

investment of capital than for the purpose of

sustaining life by personal labor. Such as

possess a considerable amount of capital, or

such as choose to adventure in commercial

speculations without capital, can alone be

fitted to be emigrants to the islands. The

agriculture of these regions, as before

observed, is a sort of commerce; and it is a

species of employment in which labor seems to

form an inconsiderable ingredient in the

productive causes, since the portion of white

labor is exceedingly small, and slave labor is

rather more like profit on stock or capital than

labor properly so called. The individual who

undertakes an establishment of this kind takes

into the account the cost of the necessary

number of slaves, in the same manner as he

calculates the cost of the land. The

uncertainty, too, of this species of employment,

affords another ground of resemblance to

commerce. Although gainful on the whole, and in

a series of years, it is often very disastrous

for a single year, and, as the capital is not

readily invested in other pursuits, bad crops or

bad markets not only affect the profits, but the

capital itself. Hence the sudden depressions

which take place in the value of such estates.

But the great and leading observation, relative

to these establishments, remains to be made. It

is, that the owners of the soil and of the

capital seldom consider themselves at home in

the colony. A very great portion of the soil

itself is usually owned in the mother country; a

still greater is mortgaged for capital obtained

there; and, in general, those who are to derive

an interest from the products look to the parent

country as the place for enjoyment of their

wealth. The population is therefore constantly

fluctuating. Nobody comes but to return. A

constant succession of owners, agents, and

factors takes place. Whatsoever the soil, forced

by the unmitigated toil of slavery, can yield,

is sent home to defray rents, and interest, and

agencies, or to give the means of living in a

better society. In such a state, it is evident

that no spirit of permanent improvement is

likely to spring up. Profits will not be

invested with a distant view of benefiting

posterity. Roads and canals will hardly be

built; schools will not be founded; colleges

will not be endowed. There will be few fixtures

in society; no principles of utility or of

elegance, planted now, with the hope of being

developed and expanded hereafter. Profit,

immediate profit, must be the principal active

spring in the social system. There may be many

particular exceptions to these general remarks,

but the outline of the whole is such as is here

drawn.

Another most important consequence of such a

state of things is, that no idea of independence

of the parent country is likely to arise;

unless, indeed, it should spring up in a form

that would threaten universal desolation. The

inhabitants have no strong attachment to the

place which they inhabit. The hope of a great

portion of them is to leave it; and their great

desire, to leave it soon. However useful they

may be to the parent state, how much soever they

may add to the conveniences and luxuries of

life, these colonies are not favored spots for

the expansion of the human mind, for the

progress of permanent improvement, or for sowing

the seeds of future independent empire.

This is page 1 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 2. Go to

page 2. Go to

page 3.

page 3.

More History

|

|