|

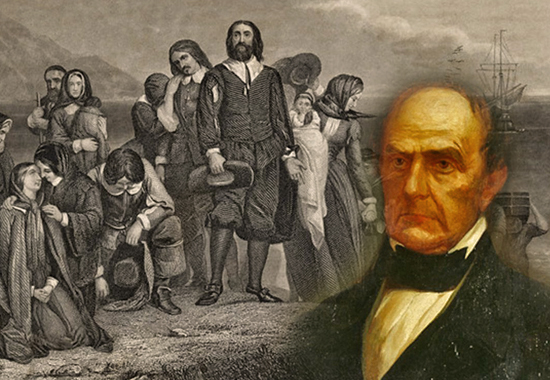

DANIEL WEBSTER COMMEMORATING THE

PILGRIM'S LANDING OF 1620

The Plymouth Oration - Page 2

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster.

Daniel Webster.

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

It follows the full text transcript of

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration, delivered at

Plymouth, Massachusetts - December 22, 1820.

This is page 2 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 1. Go to

page 1. Go to

page 3.

page 3.

Different, indeed,

most widely different, from all these instances

of emigration and plantation, were the

condition, the purposes, and the prospects of

our fathers, when they established their infant

colony upon this spot. They came hither to a

land from which they were never to return.

Hither they had brought, and here they were to

fix, their hopes, their attachments, and their

objects in life. Some natural tears they shed,

as they left the pleasant abodes of their

fathers, and some emotions they suppressed, when

the white cliffs of their native country, now

seen for the last time, grew dim to their sight.

They were acting, however, upon a resolution not

to be daunted. With whatever stifled regrets,

with whatever occasional hesitation, with

whatever appalling apprehensions, which might

sometimes arise with force to shake the firmest

purpose, they had yet committed themselves to

Heaven and the elements; and a thousand leagues

of water soon interposed to separate them for

ever from the region which gave them birth. A

new existence awaited them here; and when they

saw these shores, rough, cold, barbarous, and

barren, as then they were, they beheld their

country. That mixed and strong feeling, which we

call love of country, and which is, in general,

never extinguished in the heart of man, grasped

and embraced its proper object here. Whatever

constitutes country, except the earth and the

sun, all the moral causes of affection and

attachment which operate upon the heart, they

had brought with them to their new abode. Here

were now their families and friends, their

homes, and their property. Before they reached

the shore, they had established the elements of

a social system, and at a much earlier period

had settled their forms of religious worship. At

the moment of their landing, therefore, they

possessed institutions of government, and

institutions of religion: and friends and

families, and social and religious institutions,

framed by consent, founded on choice and

preference, how nearly do these fill up our

whole idea of country! The morning that beamed

on the first night of their repose saw the

Pilgrims already at home in their country. There

were political institutions, and civil liberty,

and religious worship. Poetry has fancied

nothing, in the wanderings of heroes, so

distinct and characteristic. Here was man,

indeed, unprotected, and unprovided for, on the

shore of a rude and fearful wilderness; but it

was politic, intelligent, and educated man.

Every thing was civilized but the physical

world. Institutions, containing in substance all

that ages had done for human government, were

organized in a forest. Cultivated mind was to

act on uncultivated nature; and, more than all,

a government and a country were to commence,

with the very first foundations laid under the

divine light of the Christian religion. Happy

auspices of a happy futurity! Who would wish

that his country's existence had otherwise

begun? Who would desire the power of going back

to the ages of fable? Who would wish for an

origin obscured in the darkness of antiquity?

Who would wish for other emblazoning of his

country's heraldry, or other ornaments of her

genealogy, than to be able to say, that her

first existence was with intelligence, her first

breath the inspiration of liberty, her first

principle the truth of divine religion?

Local attachments and sympathies would ere long

spring up in the breasts of our ancestors,

endearing to them the place of their refuge.

Whatever natural objects are associated with

interesting scenes and high efforts obtain a

hold on human feeling, and demand from the heart

a sort of recognition and regard. This Rock soon

became hallowed in the esteem of the Pilgrims,

and these hills grateful to their sight. Neither

they nor their children were again to till the

soil of England, nor again to traverse the seas

which surround her. But here was a new sea, now

open to their enterprise, and a new soil, which

had not failed to respond gratefully to their

laborious industry, and which was already

assuming a robe of verdure. Hardly had they

provided shelter for the living, ere they were

summoned to erect sepulchres for the dead. The

ground had become sacred, by enclosing the

remains of some of their companions and

connections. A parent, a child, a husband, or a

wife, had gone the way of all flesh, and mingled

with the dust of New England. We naturally look

with strong emotions to the spot, though it be a

wilderness, where the ashes of those we have

loved repose. Where the heart has laid down what

it loved most, there it is desirous of laying

itself down. No sculptured marble, no enduring

monument, no honorable inscription, no

ever-burning taper that would drive away the

darkness of the tomb, can soften our sense of

the reality of death, and hallow to our feelings

the ground which is to cover us, like the

consciousness that we shall sleep, dust to dust,

with the objects of our affections.

In a short time other causes sprung up to bind

the Pilgrims with new cords to their chosen

land. Children were born, and the hopes of

future generations arose, in the spot of their

new habitation. The second generation found this

the land of their nativity, and saw that they

were bound to its fortunes. They beheld their

fathers' graves around them, and while they read

the memorials of their toils and labors, they

rejoiced in the inheritance which they found

bequeathed to them.

Under the influence of these causes, it was to

be expected that an interest and a feeling

should arise here, entirely different from the

interest and feeling of mere Englishmen; and all

the subsequent history of the Colonies proves

this to have actually and gradually taken place.

With a general acknowledgment of the supremacy

of the British crown, there was, from the first,

a repugnance to an entire submission to the

control of British legislation. The Colonies

stood upon their charters, which, as they

contended, exempted them from the ordinary power

of the British Parliament, and authorized them

to conduct their own concerns by their own

counsels. They utterly resisted the notion that

they were to be ruled by the mere authority of

the government at home, and would not endure

even that their own charter governments should

be established on the other side of the

Atlantic. It was not a controlling or protecting

board in England, but a government of their own,

and existing immediately within their limits,

which could satisfy their wishes. It was easy to

foresee, what we know also to have happened,

that the first great cause of collision and

jealousy would be, under the notion of political

economy then and still prevalent in Europe, an

attempt on the part of the mother country to

monopolize the trade of the Colonies. Whoever

has looked deeply into the causes which produced

our Revolution has found, if I mistake not, the

original principle far back in this claim, on

the part of England, to monopolize our trade,

and a continued effort on the part of the

Colonies to resist or evade that monopoly; if,

indeed, it be not still more just and

philosophical to go farther back, and to

consider it decided, that an independent

government must arise here, the moment it was

ascertained that an English colony, such as

landed in this place, could sustain itself

against the dangers which surrounded it, and,

with other similar establishments, overspread

the land with an English population. Accidental

causes retarded at times, and at times

accelerated, the progress of the controversy.

The Colonies wanted strength, and time gave it

to them. They required measures of strong and

palpable injustice, on the part of the mother

country, to justify resistance; the early part

of the late king's reign furnished them. They

needed spirits of high order, of great daring,

of long foresight, and of commanding power, to

seize the favoring occasion to strike a blow,

which should sever, for all time, the tie of

colonial dependence; and these spirits were

found, in all the extent which that or any

crisis could demand, in Otis, Adams, Hancock,

and the other immediate authors of our

independence.

Still, it is true that, for a century, causes

had been in operation tending to prepare things

for this great result. In the year 1660 the

English Act of Navigation was passed; the first

and grand object of which seems to have been, to

secure to England the whole trade with her

plantations. It was provided by that act, that

none but English ships should transport American

produce over the ocean, and that the principal

articles of that produce should be allowed to be

sold only in the markets of the mother country.

Three years afterwards another law was passed,

which enacted, that such commodities as the

Colonies might wish to purchase should be bought

only in the markets of the mother country.

Severe rules were prescribed to enforce the

provisions of these laws, and heavy penalties

imposed on all who should violate them. In the

subsequent years of the same reign, other

statutes were enacted to re-enforce these

statutes, and other rules prescribed to secure a

compliance with these rules. In this manner was

the trade to and from the Colonies restricted,

almost to the exclusive advantage of the parent

country. But laws, which rendered the interest

of a whole people subordinate to that of another

people, were not likely to execute themselves,

nor was it easy to find many on the spot, who

could be depended upon for carrying them into

execution. In fact, these laws were more or less

evaded or resisted, in all the Colonies. To

enforce them was the constant endeavor of the

government at home; to prevent or elude their

operation, the perpetual object here. "The laws

of navigation," says a living British writer,

"were nowhere so openly disobeyed and contemned

as in New England." "The people of Massachusetts

Bay," he adds, "were from the first disposed to

act as if independent of the mother country, and

having a governor and magistrates of their own

choice, it was difficult to enforce any

regulation which came from the English

Parliament, adverse to their interests." To

provide more effectually for the execution of

these laws, we know that courts of admiralty

were afterwards established by the crown, with

power to try revenue causes, as questions of

admiralty, upon the construction given by the

crown lawyers to an act of Parliament; a great

departure from the ordinary principles of

English jurisprudence, but which has been

maintained, nevertheless, by the force of habit

and precedent, and is adopted in our own

existing systems of government.

"There lie," says another English writer, whose

connection with the Board of Trade has enabled

him to ascertain many facts connected with

Colonial history, "There lie among the documents

in the board of trade and state-paper office,

the most satisfactory proofs, from the epoch of

the English Revolution in 1688, throughout every

reign, and during every administration, of the

settled purpose of the Colonies to acquire

direct independence and positive sovereignty."

Perhaps this may be stated somewhat too

strongly; but it cannot be denied, that, from

the very nature of the establishments here, and

from the general character of the measures

respecting their concerns early adopted and

steadily pursued by the English government, a

division of the empire was the natural and

necessary result to which every thing tended.

I have dwelt on this topic, because it seems to

me, that the peculiar original character of the

New England Colonies, and certain causes coeval

with their existence, have had a strong and

decided influence on all their subsequent

history, and especially on the great event of

the Revolution. Whoever would write our history,

and would understand and explain early

transactions, should comprehend the nature and

force of the feeling which I have endeavored to

describe. As a son, leaving the house of his

father for his own, finds, by the order of

nature, and the very law of his being, nearer

and dearer objects around which his affections

circle, while his attachment to the parental

roof becomes moderated, by degrees, to a

composed regard and an affectionate remembrance;

so our ancestors, leaving their native land, not

without some violence to the feelings of nature

and affection, yet, in time, found here a new

circle of engagements, interests, and

affections; a feeling, which more and more

encroached upon the old, till an undivided

sentiment, that this was their country, occupied

the heart; and patriotism, shutting out from its

embraces the parent realm, became local to

America.

Some retrospect of the century which has now

elapsed is among the duties of the occasion. It

must, however, necessarily be imperfect, to be

compressed within the limits of a single

discourse. I shall content myself, therefore,

with taking notice of a few of the leading and

most important occurrences which have

distinguished the period.

When the first century closed, the progress of

the country appeared to have been considerable;

notwithstanding that, in comparison with its

subsequent advancement, it now seems otherwise.

A broad and lasting foundation had been laid;

excellent institutions had been established;

many of the prejudices of former times had been

removed; a more liberal and catholic spirit on

subjects of religious concern had begun to

extend itself, and many things conspired to give

promise of increasing future prosperity. Great

men had arisen in public life, and the liberal

professions. The Mathers, father and son, were

then sinking low in the western horizon;

Leverett, the learned, the accomplished, the

excellent Leverett, was about to withdraw his

brilliant and useful light. In Pemberton great

hopes had been suddenly extinguished, but Prince

and Colman were in our sky; and along the east

had begun to flash the crepuscular light of a

great luminary which was about to appear, and

which was to stamp the age with his own name, as

the age of Franklin.

The bloody Indian wars, which harassed the

people for a part of the first century; the

restrictions on the trade of the Colonies, added

to the discouragements inherently belonging to

all forms of colonial government; the distance

from Europe, and the small hope of immediate

profit to adventurers, are among the causes

which had contributed to retard the progress of

population. Perhaps it may be added, also, that

during the period of the civil wars in England,

and the reign of Cromwell, many persons, whose

religious opinions and religious temper might,

under other circumstances, have induced them to

join the New England colonists, found reasons to

remain in England; either on account of active

occupation in the scenes which were passing, or

of an anticipation of the enjoyment, in their

own country, of a form of government, civil and

religious, accommodated to their views and

principles. The violent measures, too, pursued

against the Colonies in the reign of Charles the

Second, the mockery of a trial, and the

forfeiture of the charters, were serious evils.

And during the open violences of the short reign

of James the Second, and the tyranny of Andros,

as the venerable historian of Connecticut

observes, "All the motives to great actions, to

industry, economy, enterprise, wealth, and

population, were in a manner annihilated. A

general inactivity and languishment pervaded the

public body. Liberty, property, and every thing

which ought to be dear to men, every day grew

more and more insecure."

With the Revolution in England, a better

prospect had opened on this country, as well as

on that. The joy had been as great at that

event, and far more universal, in New than in

Old England. A new charter had been granted to

Massachusetts, which, although it did not

confirm to her inhabitants all their former

privileges, yet relieved them from great evils

and embarrassments, and promised future

security. More than all, perhaps, the Revolution

in England had done good to the general cause of

liberty and justice. A blow had been struck in

favor of the rights and liberties, not of

England alone, but of descendants and kinsmen of

England all over the world. Great political

truths had been established. The champions of

liberty had been successful in a fearful and

perilous conflict. Somers, and Cavendish, and

Jekyl, and Howard, had triumphed in one of the

most noble causes ever undertaken by men. A

revolution had been made upon principle. A

monarch had been dethroned for violating the

original compact between king and people. The

rights of the people to partake in the

government, and to limit the monarch by

fundamental rules of government, had been

maintained; and however unjust the government of

England might afterwards be towards other

governments or towards her colonies, she had

ceased to be governed herself by the arbitrary

maxims of the Stuarts.

New England had submitted to the violence of

James the Second not longer than Old England.

Not only was it reserved to Massachusetts, that

on her soil should be acted the first scene of

that great revolutionary drama, which was to

take place near a century afterwards, but the

English Revolution itself, as far as the

Colonies were concerned, commenced in Boston.

The seizure and imprisonment of Andros, in

April, 1689, were acts of direct and forcible

resistance to the authority of James the Second.

The pulse of liberty beat as high in the

extremities as at the heart. The vigorous

feeling of the Colony burst out before it was

known how the parent country would finally

conduct herself. The king's representative, Sir

Edmund Andros, was a prisoner in the castle at

Boston, before it was or could be known that the

king himself had ceased to exercise his full

dominion on the English throne.

Before it was known here whether the invasion of

the Prince of Orange would or could prove

successful, as soon as it was known that it had

been undertaken, the people of Massachusetts, at

the imminent hazard of their lives and fortunes,

had accomplished the Revolution as far as

respected themselves. It is probable that,

reasoning on general principles and the known

attachment of the English people to their

constitution and liberties, and their deep and

fixed dislike of the king's religion and

politics, the people of New England expected a

catastrophe fatal to the power of the reigning

prince. Yet it was neither certain enough, nor

near enough, to come to their aid against the

authority of the crown, in that crisis which had

arrived, and in which they trusted to put

themselves, relying on God and their own

courage. There were spirits in Massachusetts

congenial with the spirits of the distinguished

friends of the Revolution in England. There were

those who were fit to associate with the boldest

asserters of civil liberty; and Mather himself,

then in England, was not unworthy to be ranked

with those sons of the Church, whose firmness

and spirit in resisting kingly encroachments in

matters of religion, entitled them to the

gratitude of their own and succeeding ages.

The second century opened upon New England under

circumstances which evinced that much had

already been accomplished, and that still better

prospects and brighter hopes were before her.

She had laid, deep and strong, the foundations

of her society. Her religious principles were

firm, and her moral habits exemplary. Her public

schools had begun to diffuse widely the elements

of knowledge; and the College, under the

excellent and acceptable administration of

Leverett, had been raised to a high degree of

credit and usefulness.

The commercial character of the country,

notwithstanding all discouragements, had begun

to display itself, and five hundred vessels,

then belonging to Massachusetts, placed her, in

relation to commerce, thus early at the head of

the Colonies. An author who wrote very near the

close of the first century says:—"New England is

almost deserving that noble name, so mightily

hath it increased; and from a small settlement

at first, is now become a very populous and

flourishing government. The capital city,

Boston, is a place of great wealth and trade;

and by much the largest of any in the English

empire of America; and not exceeded but by few

cities, perhaps two or three, in all the

American world."

But if our ancestors at the close of the first

century could look back with joy and even

admiration, at the progress of the country, what

emotions must we not feel, when, from the point

on which we stand, we also look back and run

along the events of the century which has now

closed! The country which then, as we have seen,

was thought deserving of a "noble name,"—which

then had "mightily increased," and become "very

populous,"—what was it, in comparison with what

our eyes behold it? At that period, a very great

proportion of its inhabitants lived in the

eastern section of Massachusetts proper, and in

Plymouth Colony. In Connecticut, there were

towns along the coast, some of them respectable,

but in the interior all was a wilderness beyond

Hartford. On Connecticut River, settlements had

proceeded as far up as Deerfield, and Fort

Dummer had been built near where is now the

south line of New Hampshire. In New Hampshire no

settlement was then begun thirty miles from the

mouth of Piscataqua River, and in what is now

Maine the inhabitants were confined to the

coast. The aggregate of the whole population of

New England did not exceed one hundred and sixty

thousand. Its present amount (1820) is probably

one million seven hundred thousand. Instead of

being confined to its former limits, her

population has rolled backward, and filled up

the spaces included within her actual local

boundaries. Not this only, but it has overflowed

those boundaries, and the waves of emigration

have pressed farther and farther toward the

West. The Alleghany has not checked it; the

banks of the Ohio have been covered with it. New

England farms, houses, villages, and churches

spread over and adorn the immense extent from

the Ohio to Lake Erie, and stretch along from

the Alleghany onwards, beyond the Miamis, and

toward the Falls of St. Anthony. Two thousand

miles westward from the rock where their fathers

landed, may now be found the sons of the

Pilgrims, cultivating smiling fields, rearing

towns and villages, and cherishing, we trust,

the patrimonial blessings of wise institutions,

of liberty, and religion. The world has seen

nothing like this. Regions large enough to be

empires, and which, half a century ago, were

known only as remote and unexplored

wildernesses, are now teeming with population,

and prosperous in all the great concerns of

life; in good governments, the means of

subsistence, and social happiness. It may be

safely asserted, that there are now more than a

million of people, descendants of New England

ancestry, living, free and happy, in regions

which scarce sixty years ago were tracts of

unpenetrated forest. Nor do rivers, or

mountains, or seas resist the progress of

industry and enterprise. Erelong, the sons of

the Pilgrims will be on the shores of the

Pacific. The imagination hardly keeps pace with

the progress of population, improvement, and

civilization.

It is now five-and-forty years since the growth

and rising glory of America were portrayed in

the English Parliament, with inimitable beauty,

by the most consummate orator of modern times.

Going back somewhat more than half a century,

and describing our progress as foreseen from

that point by his amiable friend Lord Bathurst,

then living, he spoke of the wonderful progress

which America had made during the period of a

single human life. There is no American heart, I

imagine, that does not glow, both with

conscious, patriotic pride, and admiration for

one of the happiest efforts of eloquence, so

often as the vision of "that little speck,

scarce visible in the mass of national interest,

a small seminal principle, rather than a formed

body," and the progress of its astonishing

development and growth, are recalled to the

recollection. But a stronger feeling might be

produced, if we were able to take up this

prophetic description where he left it, and,

placing ourselves at the point of time in which

he was speaking, to set forth with equal

felicity the subsequent progress of the country.

There is yet among the living a most

distinguished and venerable name, a descendant

of the Pilgrims; one who has been attended

through life by a great and fortunate genius; a

man illustrious by his own great merits, and

favored of Heaven in the long continuation of

his years. The time when the English orator was

thus speaking of America preceded but by a few

days the actual opening of the revolutionary

drama at Lexington. He to whom I have alluded,

then at the age of forty, was among the most

zealous and able defenders of the violated

rights of his country. He seemed already to have

filled a full measure of public service, and

attained an honorable fame. The moment was full

of difficulty and danger, and big with events of

immeasurable importance. The country was on the

very brink of a civil war, of which no man could

foretell the duration or the result. Something

more than a courageous hope, or characteristic

ardor, would have been necessary to impress the

glorious prospect on his belief, if, at that

moment, before the sound of the first shock of

actual war had reached his ears, some attendant

spirit had opened to him the vision of the

future;—if it had said to him, "The blow is

struck, and America is severed from England for

ever!"—if it had informed him, that he himself,

during the next annual revolution of the sun,

should put his own hand to the great instrument

of independence, and write his name where all

nations should behold it and all time should not

efface it; that erelong he himself should

maintain the interests and represent the

sovereignty of his newborn country in the

proudest courts of Europe; that he should one

day exercise her supreme magistracy; that he

should yet live to behold ten millions of

fellow-citizens paying him the homage of their

deepest gratitude and kindest affections; that

he should see distinguished talent and high

public trust resting where his name rested; that

he should even see with his own unclouded eyes

the close of the second century of New England,

who had begun life almost with its commencement,

and lived through nearly half the whole history

of his country; and that on the morning of this

auspicious day he should be found in the

political councils of his native State,

revising, by the light of experience, that

system of government which forty years before he

had assisted to frame and establish; and, great

and happy as he should then behold his country,

there should be nothing in prospect to cloud the

scene, nothing to check the ardor of that

confident and patriotic hope which should glow

in his bosom to the end of his long protracted

and happy life.

It would far exceed the limits of this discourse

even to mention the principal events in the

civil and political history of New England

during the century; the more so, as for the last

half of the period that history has, most

happily, been closely interwoven with the

general history of the United States. New

England bore an honorable part in the wars which

took place between England and France. The

capture of Louisburg gave her a character for

military achievement; and in the war which

terminated with the peace of 1763, her exertions

on the frontiers wore of most essential service,

as well to the mother country as to all the

Colonies.

In New England the war of the Revolution

commenced. I address those who remember the

memorable 19th of April, 1775; who shortly after

saw the burning spires of Charlestown; who

beheld the deeds of Prescott, and heard the

voice of Putnam amidst the storm of war, and saw

the generous Warren fall, the first

distinguished victim in the cause of liberty. It

would be superfluous to say, that no portion of

the country did more than the States of New

England to bring the Revolutionary struggle to a

successful issue. It is scarcely less to her

credit, that she saw early the necessity of a

closer union of the States, and gave an

efficient and indispensable aid to the

establishment and organization of the Federal

government.

Perhaps we might safely say, that a new spirit

and a new excitement began to exist here about

the middle of the last century. To whatever

causes it may be imputed, there seems then to

have commenced a more rapid improvement. The

Colonies had attracted more of the attention of

the mother country, and some renown in arms had

been acquired. Lord Chatham was the first

English minister who attached high importance to

these possessions of the crown, and who foresaw

any thing of their future growth and extension.

His opinion was, that the great rival of England

was chiefly to be feared as a maritime and

commercial power, and to drive her out of North

America and deprive her of her West Indian

possessions was a leading object in his policy.

He dwelt often on the fisheries, as nurseries

for British seamen, and the colonial trade, as

furnishing them employment. The war, conducted

by him with so much vigor, terminated in a

peace, by which Canada was ceded to England. The

effect of this was immediately visible in the

New England Colonies; for, the fear of Indian

hostilities on the frontiers being now happily

removed, settlements went on with an activity

before that time altogether unprecedented, and

public affairs wore a new and encouraging

aspect. Shortly after this fortunate termination

of the French war, the interesting topics

connected with the taxation of America by the

British Parliament began to be discussed, and

the attention and all the faculties of the

people drawn towards them. There is perhaps no

portion of our history more full of interest

than the period from 1760 to the actual

commencement of the war. The progress of opinion

in this period, though less known, is not less

important than the progress of arms afterwards.

Nothing deserves more consideration than those

events and discussions which affected the public

sentiment and settled the Revolution in men's

minds, before hostilities openly broke out.

Internal improvement followed the establishment

and prosperous commencement of the present

government. More has been done for roads,

canals, and other public works, within the last

thirty years, than in all our former history. In

the first of these particulars, few countries

excel the New England States. The astonishing

increase of their navigation and trade is known

to every one, and now belongs to the history of

our national wealth.

We may flatter ourselves, too, that literature

and taste have not been stationary, and that

some advancement has been made in the elegant,

as well as in the useful arts.

The nature and constitution of society and

government in this country are interesting

topics, to which I would devote what remains of

the time allowed to this occasion. Of our system

of government the first thing to be said is,

that it is really and practically a free system.

It originates entirely with the people, and

rests on no other foundation than their assent.

To judge of its actual operation, it is not

enough to look merely at the form of its

construction. The practical character of

government depends often on a variety of

considerations, besides the abstract frame of

its constitutional organization. Among these are

the condition and tenure of property; the laws

regulating its alienation and descent; the

presence or absence of a military power; an

armed or unarmed yeomanry; the spirit of the

age, and the degree of general intelligence. In

these respects it cannot be denied that the

circumstances of this country are most favorable

to the hope of maintaining the government of a

great nation on principles entirely popular. In

the absence of military power, the nature of

government must essentially depend on the manner

in which property is holden and distributed.

There is a natural influence belonging to

property, whether it exists in many hands or

few; and it is on the rights of property that

both despotism and unrestrained popular violence

ordinarily commence their attacks. Our ancestors

began their system of government here under a

condition of comparative equality in regard to

wealth, and their early laws were of a nature to

favor and continue this equality.

A republican form of government rests not more

on political constitutions, than on those laws

which regulate the descent and transmission of

property. Governments like ours could not have

been maintained, where property was holden

according to the principles of the feudal

system; nor, on the other hand, could the feudal

constitution possibly exist with us. Our New

England ancestors brought hither no great

capitals from Europe; and if they had, there was

nothing productive in which they could have been

invested. They left behind them the whole feudal

policy of the other continent. They broke away

at once from the system of military service

established in the Dark Ages, and which

continues, down even to the present time, more

or less to affect the condition of property all

over Europe. They came to a new country. There

were, as yet, no lands yielding rent, and no

tenants rendering service. The whole soil was

unreclaimed from barbarism. They were

themselves, either from their original

condition, or from the necessity of their common

interest, nearly on a general level in respect

to property. Their situation demanded a

parceling out and division of the lands, and it

may be fairly said, that this necessary act

fixed the future frame and form of their

government. The character of their political

institutions was determined by the fundamental

laws respecting property. The laws rendered

estates divisible among sons and daughters. The

right of primogeniture, at first limited and

curtailed, was afterwards abolished. The

property was all freehold. The entailment of

estates, long trusts, and the other processes

for fettering and tying up inheritances, were

not applicable to the condition of society, and

seldom made use of. On the contrary, alienation

of the land was every way facilitated, even to

the subjecting of it to every species of debt.

The establishment of public registries, and the

simplicity of our forms of conveyance, have

greatly facilitated the change of real estate

from one proprietor to another. The consequence

of all these causes has been a great subdivision

of the soil, and a great equality of condition;

the true basis, most certainly, of a popular

government. "If the people," says Harrington,

"hold three parts in four of the territory, it

is plain there can neither be any single person

nor nobility able to dispute the government with

them; in this case, therefore, except force be

interposed, they govern themselves."

The history of other nations may teach us how

favorable to public liberty are the division of

the soil into small freeholds, and a system of

laws, of which the tendency is, without violence

or injustice, to produce and to preserve a

degree of equality of property. It has been

estimated, if I mistake not, that about the time

of Henry the Seventh four fifths of the land in

England was holden by the great barons and

ecclesiastics. The effects of a growing commerce

soon afterwards began to break in on this state

of things, and before the Revolution, in 1688, a

vast change had been wrought. It may be thought

probable, that, for the last half-century, the

process of subdivision in England has been

retarded, if not reversed; that the great weight

of taxation has compelled many of the lesser

freeholders to dispose of their estates, and to

seek employment in the army and navy, in the

professions of civil life, in commerce, or in

the colonies. The effect of this on the British

constitution cannot but be most unfavorable. A

few large estates grow larger; but the number of

those who have no estates also increases; and

there may be danger, lest the inequality of

property become so great, that those who possess

it may be dispossessed by force; in other words,

that the government may be overturned.

This is page 2 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 1. Go to

page 1. Go to

page 3.

page 3.

More History

|

|