|

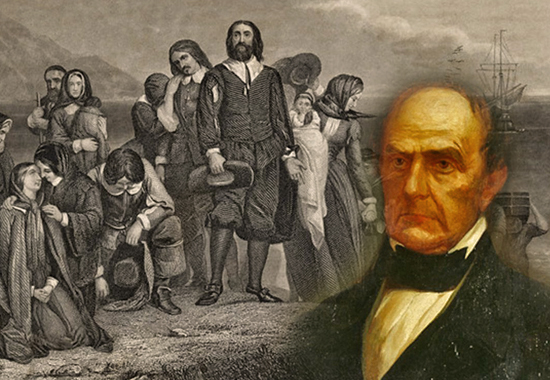

DANIEL WEBSTER COMMEMORATING THE

PILGRIM'S LANDING OF 1620

The Plymouth Oration - Page 3

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster.

Daniel Webster.

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration.

It follows the full text transcript of

Daniel Webster's Plymouth Oration, delivered at

Plymouth, Massachusetts - December 22, 1820.

This is page 3 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 1. Go to

page 1. Go to

page 2.

page 2.

A most interesting

experiment of the effect of a subdivision of

property on government is now making in France.

It is understood, that the law regulating the

transmission of property in that country, now

divides it, real and personal, among all the

children equally, both sons and daughters; and

that there is, also, a very great restraint on

the power of making dispositions of property by

will. It has been supposed, that the effects of

this might probably be, in time, to break up the

soil into such small subdivisions, that the

proprietors would be too poor to resist the

encroachments of executive power. I think far

otherwise. What is lost in individual wealth

will be more than gained in numbers, in

intelligence, and in a sympathy of sentiment.

If, indeed, only one or a few landholders were

to resist the crown, like the barons of England,

they must, of course, be great and powerful

landholders, with multitudes of retainers, to

promise success. But if the proprietors of a

given extent of territory are summoned to

resistance, there is no reason to believe that

such resistance would be less forcible, or less

successful, because the number of such

proprietors happened to be great. Each would

perceive his own importance, and his own

interest, and would feel that natural elevation

of character which the consciousness of property

inspires. A common sentiment would unite all,

and numbers would not only add strength, but

excite enthusiasm. It is true, that France

possesses a vast military force, under the

direction of an hereditary executive government;

and military power, it is possible, may

overthrow any government. It is in vain,

however, in this period of the world, to look

for security against military power to the arm

of the great landholders. That notion is derived

from a state of things long since past; a state

in which a feudal baron, with his retainers,

might stand against the sovereign and his

retainers, himself but the greatest baron. But

at present, what could the richest landholder

do, against one regiment of disciplined troops?

Other securities, therefore, against the

prevalence of military power must be provided.

Happily for us, we are not so situated as that

any purpose of national defense requires,

ordinarily and constantly, such a military force

as might seriously endanger our liberties.

In respect, however, to the recent law of

succession in France, to which I have alluded, I

would, presumptuously perhaps, hazard a

conjecture, that, if the government do not

change the law, the law in half a century will

change the government; and that this change will

be, not in favor of the power of the crown, as

some European writers have supposed, but against

it. Those writers only reason upon what they

think correct general principles, in relation to

this subject. They acknowledge a want of

experience. Here we have had that experience;

and we know that a multitude of small

proprietors, acting with intelligence, and that

enthusiasm which a common cause inspires,

constitute not only a formidable, but an

invincible power.

The true principle of a free and popular

government would seem to be, so to construct it

as to give to all, or at least to a very great

majority, an interest in its preservation; to

found it, as other things are founded, on men's

interest. The stability of government demands

that those who desire its continuance should be

more powerful than those who desire its

dissolution. This power, of course, is not

always to be measured by mere numbers.

Education, wealth, talents, are all parts and

elements of the general aggregate of power; but

numbers, nevertheless, constitute ordinarily the

most important consideration, unless, indeed,

there be a military force in the hands of the

few, by which they can control the many. In this

country we have actually existing systems of

government, in the maintenance of which, it

should seem, a great majority, both in numbers

and in other means of power and influence, must

see their interest. But this state of things is

not brought about solely by written political

constitutions, or the mere manner of organizing

the government; but also by the laws which

regulate the descent and transmission of

property. The freest government, if it could

exist, would not be long acceptable, if the

tendency of the laws were to create a rapid

accumulation of property in few hands, and to

render the great mass of the population

dependent and penniless. In such a case, the

popular power would be likely to break in upon

the rights of property, or else the influence of

property to limit and control the exercise of

popular power. Universal suffrage, for example,

could not long exist in a community where there

was great inequality of property. The holders of

estates would be obliged, in such case, in some

way to restrain the right of suffrage, or else

such right of suffrage would, before long,

divide the property. In the nature of things,

those who have not property, and see their

neighbors possess much more than they think them

to need, cannot be favorable to laws made for

the protection of property. When this class

becomes numerous, it grows clamorous. It looks

on property as its prey and plunder, and is

naturally ready, at all times, for violence and

revolution.

It would seem, then, to be the part of political

wisdom to found government on property; and to

establish such distribution of property, by the

laws which regulate its transmission and

alienation, as to interest the great majority of

society in the support of the government. This

is, I imagine, the true theory and the actual

practice of our republican institutions. With

property divided as we have it, no other

government than that of a republic could be

maintained, even were we foolish enough to

desire it. There is reason, therefore, to expect

a long continuance of our system. Party and

passion, doubtless, may prevail at times, and

much temporary mischief be done. Even modes and

forms may be changed, and perhaps for the worse.

But a great revolution in regard to property

must take place, before our governments can be

moved from their republican basis, unless they

be violently struck off by military power. The

people possess the property, more emphatically

than it could ever be said of the people of any

other country, and they can have no interest to

overturn a government which protects that

property by equal laws.

Let it not be supposed, that this state of

things possesses too strong tendencies towards

the production of a dead and uninteresting level

in society. Such tendencies are sufficiently

counteracted by the infinite diversities in the

characters and fortunes of individuals. Talent,

activity, industry, and enterprise tend at all

times to produce inequality and distinction; and

there is room still for the accumulation of

wealth, with its great advantages, to all

reasonable and useful extent. It has been often

urged against the state of society in America,

that it furnishes no class of men of fortune and

leisure. This may be partly true, but it is not

entirely so, and the evil, if it be one, would

affect rather the progress of taste and

literature, than the general prosperity of the

people. But the promotion of taste and

literature cannot be primary objects of

political institutions; and if they could, it

might be doubted whether, in the long course of

things, as much is not gained by a wide

diffusion of general knowledge, as is lost by

diminishing the number of those who are enabled

by fortune and leisure to devote themselves

exclusively to scientific and literary pursuits.

However this may be, it is to be considered that

it is the spirit of our system to be equal and

general, and if there be particular

disadvantages incident to this, they are far

more than counterbalanced by the benefits which

weigh against them. The important concerns of

society are generally conducted, in all

countries, by the men of business and practical

ability; and even in matters of taste and

literature, the advantages of mere leisure are

liable to be overrated. If there exist adequate

means of education and a love of letters be

excited, that love will find its way to the

object of its desire, through the crowd and

pressure of the most busy society.

Connected with this division of property, and

the consequent participation of the great mass

of people in its possession and enjoyments, is

the system of representation, which is admirably

accommodated to our condition, better understood

among us, and more familiarly and extensively

practiced, in the higher and in the lower

departments of government, than it has been by

any other people. Great facility has been given

to this in New England by the early division of

the country into townships or small districts,

in which all concerns of local police are

regulated, and in which representatives to the

legislature are elected. Nothing can exceed the

utility of these little bodies. They are so many

councils or parliaments, in which common

interests are discussed, and useful knowledge

acquired and communicated.

The division of governments into departments,

and the division, again, of the legislative

department into two chambers, are essential

provisions in our system. This last, although

not new in itself, yet seems to be new in its

application to governments wholly popular. The

Grecian republics, it is plain, knew nothing of

it; and in Rome, the check and balance of

legislative power, such as it was, lay between

the people and the senate. Indeed, few things

are more difficult than to ascertain accurately

the true nature and construction of the Roman

commonwealth. The relative power of the senate

and the people, of the consuls and the tribunes,

appears not to have been at all times the same,

nor at any time accurately defined or strictly

observed. Cicero, indeed, describes to us an

admirable arrangement of political power, and a

balance of the constitution, in that beautiful

passage, in which he compares the democracies of

Greece with the Roman commonwealth.

"O morem preclarum,

disciplinamque, quam a majoribus accepimus, si

quidem teneremus! sed nescio quo pacto jam de

manibus elabitur. Nullam enim illi nostri

sapientissimi et sanctissimi viri vim concionis

esse voluerunt, quae scisseret plebs, aut quae

populus juberet; summota concione, distributis

partibus, tributim et centuriatim descriptis

ordinibus, classibus, aetatibus, auditis

auctoribus, re multos dies promulgata et cognita,

juberi vetarique voluerunt. Graecorum autem

totae respublicae sedentis concionis temeritate

administrantur."

But at what time this wise system existed in

this perfection at Rome, no proofs remain to

show. Her constitution, originally framed for a

monarchy, never seemed to be adjusted in its

several parts after the expulsion of the kings.

Liberty there was, but it was a disputatious, an

uncertain, an ill-secured liberty. The patrician

and plebeian orders, instead of being matched

and joined, each in its just place and

proportion, to sustain the fabric of the state,

were rather like hostile powers, in perpetual

conflict. With us, an attempt has been made, and

so far not without success, to divide

representation into chambers, and, by difference

of age, character, qualification, or mode of

election, to establish salutary checks, in

governments altogether elective.

Having detained you so long with these

observations, I must yet advert to another most

interesting topic,—the Free Schools. In this

particular, New England may be allowed to claim,

I think, a merit of a peculiar character. She

early adopted, and has constantly maintained the

principle, that it is the undoubted right and

the bounden duty of government to provide for

the instruction of all youth. That which is

elsewhere left to chance or to charity, we

secure by law. For the purpose of public

instruction, we hold every man subject to

taxation in proportion to his property, and we

look not to the question, whether he himself

have, or have not, children to be benefited by

the education for which he pays. We regard it as

a wise and liberal system of police, by which

property, and life, and the peace of society are

secured. We seek to prevent in some measure the

extension of the penal code, by inspiring a

salutary and conservative principle of virtue

and of knowledge in an early age. We strive to

excite a feeling of respectability, and a sense

of character, by enlarging the capacity and

increasing the sphere of intellectual enjoyment.

By general instruction, we seek, as far as

possible, to purify the whole moral atmosphere;

to keep good sentiments uppermost, and to turn

the strong current of feeling and opinion, as

well as the censures of the law and the

denunciations of religion, against immorality

and crime. We hope for a security beyond the

law, and above the law, in the prevalence of an

enlightened and well-principled moral sentiment.

We hope to continue and prolong the time, when,

in the villages and farm-houses of New England,

there may be undisturbed sleep within unbarred

doors. And knowing that our government rests

directly on the public will, in order that we

may preserve it we endeavor to give a safe and

proper direction to that public will. We do not,

indeed, expect all men to be philosophers or

statesmen; but we confidently trust, and our

expectation of the duration of our system of

government rests on that trust, that, by the

diffusion of general knowledge and good and

virtuous sentiments, the political fabric may be

secure, as well against open violence and

overthrow, as against the slow, but sure,

undermining of licentiousness.

We know that, at the present time, an attempt is

making in the English Parliament to provide by

law for the education of the poor, and that a

gentleman of distinguished character (Mr.

Brougham) has taken the lead in presenting a

plan to government for carrying that purpose

into effect. And yet, although the

representatives of the three kingdoms listened

to him with astonishment as well as delight, we

hear no principles with which we ourselves have

not been familiar from youth; we see nothing in

the plan but an approach towards that system

which has been established in New England for

more than a century and a half. It is said that

in England not more than one child in fifteen

possesses the means of being taught to read and

write; in Wales, one in twenty; in France, until

lately, when some improvement was made, not more

than one in thirty-five. Now, it is hardly too

strong to say, that in New England every child

possesses such means. It would be difficult to

find an instance to the contrary, unless where

it should be owing to the negligence of the

parent; and, in truth, the means are actually

used and enjoyed by nearly every one. A youth of

fifteen, of either sex, who cannot both read and

write, is very seldom to be found. Who can make

this comparison, or contemplate this spectacle,

without delight and a feeling of just pride?

Does any history show property more beneficently

applied? Did any government ever subject the

property of those who have estates to a burden,

for a purpose more favorable to the poor, or

more useful to the whole community?

A conviction of the importance of public

instruction was one of the earliest sentiments

of our ancestors. No lawgiver of ancient or

modern times has expressed more just opinions,

or adopted wiser measures, than the early

records of the Colony of Plymouth show to have

prevailed here. Assembled on this very spot, a

hundred and fifty-three years ago, the

legislature of this Colony declared, "Forasmuch

as the maintenance of good literature doth much

tend to the advancement of the weal and

flourishing state of societies and republics,

this Court doth therefore order, that in

whatever township in this government, consisting

of fifty families or upwards, any meet man shall

be obtained to teach a grammar school, such

township shall allow at least twelve pounds, to

be raised by rate on all the inhabitants."

Having provided that all youth should be

instructed in the elements of learning by the

institution of free schools, our ancestors had

yet another duty to perform. Men were to be

educated for the professions and the public. For

this purpose they founded the University, and

with incredible zeal and perseverance they

cherished and supported it, through all trials

and discouragements. On the subject of the

University, it is not possible for a son of New

England to think without pleasure, or to speak

without emotion. Nothing confers more honor on

the State where it is established, or more

utility on the country at large. A respectable

university is an establishment which must be the

work of time. If pecuniary means were not

wanting, no new institution could possess

character and respectability at once. We owe

deep obligation to our ancestors, who began,

almost on the moment of their arrival, the work

of building up this institution.

Although established in a different government,

the Colony of Plymouth manifested warm

friendship for Harvard College. At an early

period, its government took measures to promote

a general subscription throughout all the towns

in this Colony, in aid of its small funds. Other

colleges were subsequently founded and endowed,

in other places, as the ability of the people

allowed; and we may flatter ourselves, that the

means of education at present enjoyed in New

England are not only adequate to the diffusion

of the elements of knowledge among all classes,

but sufficient also for respectable attainments

in literature and the sciences.

Lastly, our ancestors established their system

of government on morality and religious

sentiment. Moral habits, they believed, cannot

safely be trusted on any other foundation than

religious principle, nor any government be

secure which is not supported by moral habits.

Living under the heavenly light of revelation,

they hoped to find all the social dispositions,

all the duties which men owe to each other and

to society, enforced and performed. Whatever

makes men good Christians, makes them good

citizens. Our fathers came here to enjoy their

religion free and unmolested; and, at the end of

two centuries, there is nothing upon which we

can pronounce more confidently, nothing of which

we can express a more deep and earnest

conviction, than of the inestimable importance

of that religion to man, both in regard to this

life and that which is to come.

If the blessings of our political and social

condition have not been too highly estimated, we

cannot well overrate the responsibility and duty

which they impose upon us. We hold these

institutions of government, religion, and

learning, to be transmitted, as well as enjoyed.

We are in the line of conveyance, through which

whatever has been obtained by the spirit and

efforts of our ancestors is to be communicated

to our children.

We are bound to maintain public liberty, and, by

the example of our own systems, to convince the

world that order and law, religion and morality,

the rights of conscience, the rights of persons,

and the rights of property, may all be preserved

and secured, in the most perfect manner, by a

government entirely and purely elective. If we

fail in this, our disaster will be signal, and

will furnish an argument, stronger than has yet

been found, in support of those opinions which

maintain that government can rest safely on

nothing but power and coercion. As far as

experience may show errors in our

establishments, we are bound to correct them;

and if any practices exist contrary to the

principles of justice and humanity within the

reach of our laws or our influence, we are

inexcusable if we do not exert ourselves to

restrain and abolish them.

I deem it my duty on this occasion to suggest,

that the land is not yet wholly free from the

contamination of a traffic, at which every

feeling of humanity must for ever revolt,—I mean

the African slave-trade. Neither public

sentiment, nor the law, has hitherto been able

entirely to put an end to this odious and

abominable trade. At the moment when God in his

mercy has blessed the Christian world with a

universal peace, there is reason to fear, that,

to the disgrace of the Christian name and

character, new efforts are making for the

extension of this trade by subjects and citizens

of Christian states, in whose hearts there dwell

no sentiments of humanity or of justice, and

over whom neither the fear of God nor the fear

of man exercises a control. In the sight of our

law, the African slave-trader is a pirate and a

felon; and in the sight of Heaven, an offender

far beyond the ordinary depth of human guilt.

There is no brighter page of our history, than

that which records the measures which have been

adopted by the government at an early day, and

at different times since, for the suppression of

this traffic; and I would call on all the true

sons of New England to co-operate with the laws

of man, and the justice of Heaven. If there be,

within the extent of our knowledge or influence,

any participation in this traffic, let us pledge

ourselves here, upon the rock of Plymouth, to

extirpate and destroy it. It is not fit that the

land of the Pilgrims should bear the shame

longer. I hear the sound of the hammer, I see

the smoke of the furnaces where manacles and

fetters are still forged for human limbs. I see

the visages of those who by stealth and at

midnight labor in this work of hell, foul and

dark, as may become the artificers of such

instruments of misery and torture. Let that spot

be purified, or let it cease to be of New

England. Let it be purified, or let it be set

aside from the Christian world; let it be put

out of the circle of human sympathies and human

regards, and let civilized man henceforth have

no communion with it.

I would invoke those who fill the seats of

justice, and all who minister at her altar, that

they execute the wholesome and necessary

severity of the law. I invoke the ministers of

our religion, that they proclaim its

denunciation of these crimes, and add its solemn

sanctions to the authority of human laws. If the

pulpit be silent whenever or wherever there may

be a sinner bloody with this guilt within the

hearing of its voice, the pulpit is false to its

trust. I call on the fair merchant, who has

reaped his harvest upon the seas, that he assist

in scourging from those seas the worst pirates

that ever infested them. That ocean, which seems

to wave with a gentle magnificence to waft the

burden of an honest commerce, and to roll along

its treasures with a conscious pride,—that

ocean, which hardy industry regards, even when

the winds have ruffled its surface, as a field

of grateful toil,—what is it to the victim of

this oppression, when he is brought to its

shores, and looks forth upon it, for the first

time, loaded with chains, and bleeding with

stripes? What is it to him but a wide-spread

prospect of suffering, anguish, and death? Nor

do the skies smile longer, nor is the air longer

fragrant to him. The sun is cast down from

heaven. An inhuman and accursed traffic has cut

him off in his manhood, or in his youth, from

every enjoyment belonging to his being, and

every blessing which his Creator intended for

him.

The Christian communities send forth their

emissaries of religion and letters, who stop,

here and there, along the coast of the vast

continent of Africa, and with painful and

tedious efforts make some almost imperceptible

progress in the communication of knowledge, and

in the general improvement of the natives who

are immediately about them. Not thus slow and

imperceptible is the transmission of the vices

and bad passions which the subjects of Christian

states carry to the land. The slave-trade having

touched the coast, its influence and its evils

spread, like a pestilence, over the whole

continent, making savage wars more savage and

more frequent, and adding new and fierce

passions to the contests of barbarians.

I pursue this topic no further, except again to

say, that all Christendom, being now blessed

with peace, is bound by every thing which

belongs to its character, and to the character

of the present age, to put a stop to this

inhuman and disgraceful traffic.

We are bound, not only to maintain the general

principles of public liberty, but to support

also those existing forms of government which

have so well secured its enjoyment, and so

highly promoted the public prosperity. It is now

more than thirty years that these States have

been united under the Federal Constitution, and

whatever fortune may await them hereafter, it is

impossible that this period of their history

should not be regarded as distinguished by

signal prosperity and success. They must be

sanguine indeed, who can hope for benefit from

change. Whatever division of the public judgment

may have existed in relation to particular

measures of the government, all must agree, one

should think, in the opinion, that in its

general course it has been eminently productive

of public happiness. Its most ardent friends

could not well have hoped from it more than it

has accomplished; and those who disbelieved or

doubted ought to feel less concern about

predictions which the event has not verified,

than pleasure in the good which has been

obtained. Whoever shall hereafter write this

part of our history, although he may see

occasional errors or defects, will be able to

record no great failure in the ends and objects

of government. Still less will he be able to

record any series of lawless and despotic acts,

or any successful usurpation. His page will

contain no exhibition of provinces depopulated,

of civil authority habitually trampled down by

military power, or of a community crushed by the

burden of taxation. He will speak, rather, of

public liberty protected, and public happiness

advanced; of increased revenue, and population

augmented beyond all example; of the growth of

commerce, manufactures, and the arts; and of

that happy condition, in which the restraint and

coercion of government are almost invisible and

imperceptible, and its influence felt only in

the benefits which it confers. We can entertain

no better wish for our country, than that this

government may be preserved; nor have a clearer

duty than to maintain and support it in the full

exercise of all its just constitutional powers.

The cause of science and literature also imposes

upon us an important and delicate trust. The

wealth and population of the country are now so

far advanced, as to authorize the expectation of

a correct literature and a well formed taste, as

well as respectable progress in the abstruse

sciences. The country has risen from a state of

colonial subjection; it has established an

independent government, and is now in the

undisturbed enjoyment of peace and political

security. The elements of knowledge are

universally diffused, and the reading portion of

the community is large. Let us hope that the

present may be an auspicious era of literature.

If, almost on the day of their landing, our

ancestors founded schools and endowed colleges,

what obligations do not rest upon us, living

under circumstances so much more favorable both

for providing and for using the means of

education? Literature becomes free institutions.

It is the graceful ornament of civil liberty,

and a happy restraint on the asperities which

political controversies sometimes occasion. Just

taste is not only an embellishment of society,

but it rises almost to the rank of the virtues,

and diffuses positive good throughout the whole

extent of its influence. There is a connection

between right feeling and right principles, and

truth in taste is allied with truth in morality.

With nothing in our past history to discourage

us, and with something in our present condition

and prospects to animate us, let us hope, that,

as it is our fortune to live in an age when we

may behold a wonderful advancement of the

country in all its other great interests, we may

see also equal progress and success attend the

cause of letters.

Finally, let us not forget the religious

character of our origin. Our fathers were

brought hither by their high veneration for the

Christian religion. They journeyed by its light,

and labored in its hope. They sought to

incorporate its principles with the elements of

their society, and to diffuse its influence

through all their institutions, civil,

political, or literary. Let us cherish these

sentiments, and extend this influence still more

widely; in the full conviction, that that is the

happiest society which partakes in the highest

degree of the mild and peaceful spirit of

Christianity.

The hours of this day are rapidly flying, and

this occasion will soon be passed. Neither we

nor our children can expect to behold its

return. They are in the distant regions of

futurity, they exist only in the all-creating

power of God, who shall stand here a hundred

years hence, to trace, through us, their descent

from the Pilgrims, and to survey, as we have now

surveyed, the progress of their country, during

the lapse of a century. We would anticipate

their concurrence with us in our sentiments of

deep regard for our common ancestors. We would

anticipate and partake the pleasure with which

they will then recount the steps of New

England's advancement. On the morning of that

day, although it will not disturb us in our

repose, the voice of acclamation and gratitude,

commencing on the Rock of Plymouth, shall be

transmitted through millions of the sons of the

Pilgrims, till it lose itself in the murmurs of

the Pacific seas.

We would leave for the consideration of those

who shall then occupy our places, some proof

that we hold the blessings transmitted from our

fathers in just estimation; some proof of our

attachment to the cause of good government, and

of civil and religious liberty; some proof of a

sincere and ardent desire to promote every thing

which may enlarge the understandings and improve

the hearts of men. And when, from the long

distance of a hundred years, they shall look

back upon us, they shall know, at least, that we

possessed affections, which, running backward

and warming with gratitude for what our

ancestors have done for our happiness, run

forward also to our posterity, and meet them

with cordial salutation, ere yet they have

arrived on the shore of being.

Advance, then, ye future generations! We would

hail you, as you rise in your long succession,

to fill the places which we now fill, and to

taste the blessings of existence where we are

passing, and soon shall have passed, our own

human duration. We bid you welcome to this

pleasant land of the fathers. We bid you welcome

to the healthful skies and the verdant fields of

New England. We greet your accession to the

great inheritance which we have enjoyed.

We welcome you to

the blessings of good government and religious

liberty. We welcome you to the treasures of

science and the delights of learning. We welcome

you to the transcendent sweets of domestic life,

to the happiness of kindred, and parents, and

children. We welcome you to the immeasurable

blessings of rational existence, the immortal

hope of Christianity, and the light of

everlasting truth!

This is page 3 of 3 of Webster's

Plymouth Oration.

Go to

page 1. Go to

page 1. Go to

page 2.

page 2.

More History

|

|