|

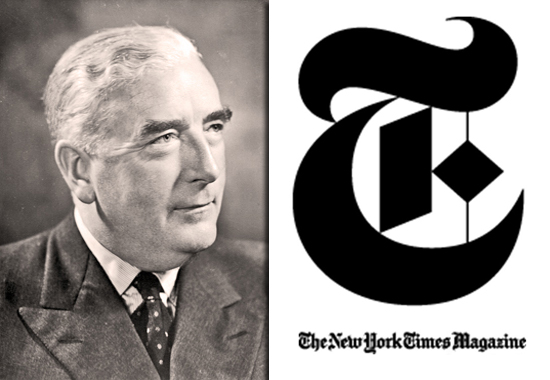

ROBERT MENZIES PUBLISHED BY NEW YORK

TIMES MAGAZINE

Politics as an Art

It follows the full text transcript of

Robert Menzies' article entitled Politics as

an art, as published by New York Times Magazine —

November 28, 1948.

|

Here is my thesis. |

The business of

politics is of supreme importance. Politics is

both a fine art and an inexact science. We have

concentrated upon its scientific aspects – the

measurement and estimation of economic trends,

the organization of finance, the devising of

plans for social security, the discovery of what

to do. We have neglected it as an art, the

delineating and practice of how and when to do

these things and above all, how to persuade a

self-governing people to accept and loyally

observe them. This neglect is of crucial

importance, for I am prepared to assert that it

is only if the art of politics succeeds that the

science of politics will be efficiently studied

and mastered.

In short, the art is no less important than the

science. In these days this sounds like a

paradox. But it should not surprise any student

of twentieth-century history, for history is a

tragic story of how science (which so easily

becomes an instrument of hatred and destruction)

has outrun the art of living, to the singular

discomfort and confusion and almost to the ruin

of mankind.

As one who has for twenty years been engaged in

political work in his own country, I have been

continually surprised and dejected at the

indifference to politics shown by so many

thousands of active, intelligent and

well-informed men and women. Their spoken

attitude is either one of contempt for

‘politicians’ and all their works, or one of

indifference. ‘I am much too busy to bother

about politics.’ Yet, not only all the major

economic conditions of their ordinary lives, but

also all the great factors which determine peace

or war, international co-operation or conflict,

are the creatures of politics and of political

action. To despise or ignore them is therefore a

sort of suicidal folly.

Such attitudes are the evidence, not of a

superior intelligence, but of a defective

sensibility and imagination. Tariffs, taxes,

plans of national development, the proportion

which exists or should exist between the

administrative and the productive groups, the

facilitation and control of transport, monetary

policies, services of health, the provision and

conditioning of social benefits and industrial

security, these and a hundred other great

elements are the product of the applied science

of politics.

In the daily life of the plain citizen there is

scarcely one hour or one activity which is

unaffected by what the politicians in Congress

or Parliament determine. Even those who seek to

diminish the activities of government and

believe that we are passing too readily from the

productive to the paternal and perhaps to the

authoritarian state cannot reduce the area of

political action except by the use of political

action.

That, briefly stated, is why I believe that

politics is the most important and responsible

civil activity to which a man may devote his

character, his talents, and his energy. We must,

in our own interests, elevate politics into

statesmanship and statecraft. We must aim at a

condition of affairs in which we shall no longer

reserve the dignified name of statesman for a

Churchill or a Roosevelt, but extend it to

lesser men who give honorable and patriotic

service in public affairs.

It is true that most men of ability prefer the

objective work of science, the law, literature,

scholarship, or the immediately stimulating and

profitable work of manufacturing, commerce, or

finance.

The result is that our legislative assemblies

are a fair popular cross-section, not a corps

d'elite. The first-class mind is comparatively

rare. We discourage young men of parts by

confronting them with poor material rewards,

precariousness of tenure, an open public

cynicism about their motives, and cheap sneers

about their real or supposed search for

publicity.

The reason for this wrong-headedness, so

damaging to ourselves, is that we have treated

democracy as an end and not as a means. It is

almost as if we had said, when legislatures

freely elected by the votes of all adult

citizens came into being, 'Well, thank heaven we

have achieved democracy. Let us now devote our

attention to something new.' Yet the true task

of the democrat only begins when he is put in

possession of the instruments by which the

popular will may be translated into

authoritative action. In brief, we cannot

sensibly devote only one per cent of our time to

something which affects ninety-nine per cent of

our living.

How, then, are we to attract into the political

service of the nation more and more people of

unusual gifts? Not merely by the attraction of

the scientific aspect of politics, for science

must be in its nature objective. It concerns

itself with the absolute truth, not with the

best realizable compromise. The pure political

scientist would die of frustration after a year

or two spent in public affairs. The real

attraction must be that of the art of politics,

through which alone the political scientist will

get his chance, and by which alone the results

of his labors will, in greater or lesser degree,

be put into operation.

What is the art of politics? As one of its most

indifferent practitioners, I hesitate to answer

that question. In any event no answer can be

exhaustive. I shall therefore put my answer in

several ways.

First, briefly, the art of politics is, in

relation to public affairs, to provide

exposition, persuasion, and inspiration. As the

answer has a sort of echo in it of the more

tedious forms of after-dinner oratory I make my

second.

It is that the art of politics embraces all the

following elements:

By speech or writing or both to convey political

ideas to others. (You might, in fact, say ‘to

others and to yourself’, for many a speaker or

writer has for the first time clarified his own

mind in the course of endeavoring to convey his

ideas to others. This is a phenomenon well known

to many advocates and even to some judges!)

To secure the acceptance of those ideas by a

majority.

To create a firm and understanding public

opinion which will see that they are translated

into action.

To accustom people to thinking, not only of the

immediate present or of the next election, but

of the future of a long-range and comprehensive

way.

To temper the frequently absurd asperities of

political conflict by seeking to stir up only

noble and humane emotions, since ignoble

passions, so easily aroused, can in the nature

of things produce only ignoble policies and

unfair administration.

Above all – for it is the only element which can

make the magnificent conception of democracy

result in the birth of true and brotherly human

freedom – to encourage a wide realization that

every right connotes a duty; that my rights are

conditioned upon some other fellow’s performance

of his duty to me, and that his rights will

disappear unless I do my duty by him.

By way of third answer, let me now make a few

practical working comments upon some of these

elements.

We are no doubt fine fellows, but on the whole

we are neglecting the art of speech. There are

plenty of speakers and much willingness. But on

public occasions, great or small, there is a

growing disposition to read an essay and to read

it in a singularly dull way, with head bowed

over the typescript, without pause or emphasis,

or point or climax. If we are satisfied that our

speeches are going to be eagerly read by

posterity, this may be a good idea. But for most

of us the essence of a speech is that it should

reach the hearts and minds of our immediate

audience. It must therefore be made to them and

not merely in their presence.

The frequent and indiscriminating praise of that

rather misunderstood thing called ‘oratory’ has,

I sometimes think, tended adversely to affect

the quality of public speech. After all, the

essence of a good speech is that the speaker

should have something to say which he is

resolved to convey to his listeners in the

simplest, most intelligible, and most persuasive

language. He must command his own words and not

become their incoherent victim. The search for

elaboration rather than simplicity is a mark of

the second-rate. Lucidity has always seemed to

me to be one of the cardinal virtues. The

occasional passages of noble and moving English

which have flowered in the speeches of a Pitt, a

Lincoln, a Churchill, were the inevitable

produce of sincerity, originality of mind, and

deep emotion. They cannot be forced without

being destroyed. They certainly cannot be

consciously imitated.

Two modern devices are, in my opinion, acting

adversely to good public speech. One is

amplification by the microphone. Sometimes it is

necessary. But we are getting into the habit of

using it, even for indoor meetings of a few

hundred people. In the result, it is impairing

our faculties of speech by making the proper

pitching and modulation of our voices

irrelevant. It eliminates the curiously moving

quality of the human voice, directly heard. It

is destroying the faculty of listening because

people who are accustomed to the deafening blare

of an amplifier find the unassisted voice thin

and (so they think) inaudible. This destruction

of the old intimate contact between speaker and

audience is a dangerous enemy to that simple,

direct communication which is of the essence of

true, unexaggerated public advocacy.

The other dangerous modern device is one for

which the press must accept a share of

responsibility. So great is the natural anxiety

of newspapers to be ‘first with the latest’ that

important speeches are nowadays ‘reported’

before they are delivered. That is to say they

are prepared and distributed before they are

spoken.

This has made fashionable and perhaps inevitable

the reading of speeches. It is, to me, a

deplorable thing. The speech ceases to be the

obvious expression of the speaker’s personality

and ideas, since anybody may have written it.

The speaker himself misses the stimulus which

comes from addressing a living meeting, the

impact upon his own mind which a good audience

can procure. His speech loses flexibility. It

all too frequently ceases to persuade because

persuasion depends upon the creation in the mind

of the listener of a feeling that the speaker is

addressing him, man to man, and is dealing with

the point that is troubling his mind.

To many people the art of politics is the art of

propaganda. This is, in a sense, true. But

again, we must be careful and intelligent if we

are not to injure democracy. Extravagance of

propaganda defeats itself in the long run, for,

while it deludes some, it nauseates others. In

my experience personal attacks usually injure

the attacker. Yet the practice flourishes. I

think we discourage many people from entering

public life by our absurd habit, not peculiar to

any one country, of seeking emphasis by violence

and exaggeration rather than by the making of

the fair concession which renders the subsequent

criticism so much more effective. Plain people

are more likely to believe that your political

opponent is a decent fellow, like themselves,

but wrong on some great issue, than that he is a

consummate rogue whose public errors are

doubtless the product of a corrupt and murky

private life.

But perhaps the worst attack upon the true art

of politics is made by those who cater for those

who want their politics served up to them in the

form of personal gossip, of chance remarks in

corridors, of hints and speculations and rumors.

The greater the target, the more it attracts the

arrows of the mean and the malicious. The more

prevalent this debased view of the art of

politics, the fewer people of character and

sensibility shall we attract into its service.

Again, the business of political warfare is not

to destroy your opponent, but to defeat him. It

is one of the glories of our system that it

provides not only for government but for

opposition. As one who has been a Prime Minister

and a Leader of the Opposition, I can say quite

confidently that just as there can be no good or

stable government without a sound majority, so

there will be a dictatorial government unless

there is the constant criticism of an

intelligent, active, and critical opposition.

Finally, if the democratic politician is really

to understand the importance of his art and

practice it, he must be a leader. It is still as

true as it was when Edmund Burke said it, that a

Member of Parliament is not a delegate but a

representative, bound to bring not merely his

vote but his judgment to the service of his

people. Just as a democracy cannot be preserved

in war without a great and prevailing physical

courage, so it cannot be wisely governed and

preserved in peace without moral courage.

All of us who are in politics are disposed to be

nervous about current opinion in the electorate.

This nervousness is, so to speak, our

occupational disease. We therefore need to

remind ourselves frequently that we who are in

Congress or Parliament are expected to know more

about political issues than private citizens. We

have great opportunities of study, more

authoritative sources of information, a better

chance of hearing and considering both sides. We

owe our constituents guidance. We are not bound

to spend our days, like the gentleman in the old

bromide, ‘sitting on a fence with both ears to

the ground’.

I will say nothing about Philip Drunk or Philip

Sober, for such references are always

misinterpreted. But I will say that the art of

politics is not that of devising ways and means

of securing the overthrow of informed judgment

by hasty and misinformed opinion, of considered

policy by sudden mass emotion. The regiments of

politics cannot, with safety to the state, be

led from behind.

Many of us, with sincere respect for the

carefulness and accuracy of such poll takers as

Dr Gallup, are anxious about the effect which

this new technique will have upon the practice

of politics. If it serves to tell the politician

of widely entertained errors which he must

attack, well and good. But if it merely tells

him to beware, because opinion is against him,

many good ideas will, I fear, be abandoned and

Gilbert’s Duke of Plaza Toro may yet be a

President or Prime Minister.

This little essay, may I say before I close, is

not (though it may seem so) a guide lecture for

beginners by One who Knows. Its arguments are,

on the contrary, derived from a political

experience in which I have been guilty of

practically every indicated error, every fault.

But one may have a passion for art without being

a great artist.

More History

|

|