|

THE UNITED STATES SENATE 1850

The Constitution and the Union

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster Daniel Webster

Go here for more about

Daniel Webster's Constitution and

Union Speech Daniel Webster's Constitution and

Union Speech

|

|

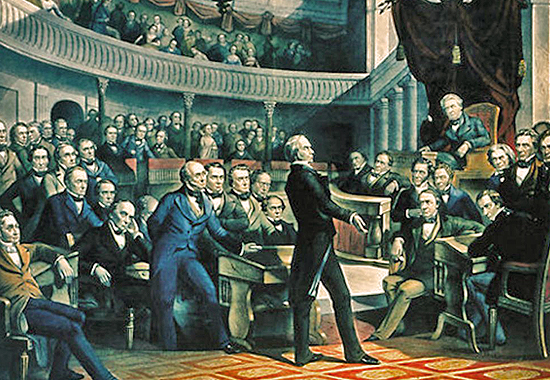

Image Above

"The United States Senate, A.D. 1850"

engraved by Robert Whitechurch after a painting by Peter Rothermel, 1855

In

this painting Webster sits on the left, holding his head

with one hand while listening to Henry Clay, who has the

floor.

|

It follows the full text transcript of

Daniel Webster's Constitution and Union speech, delivered at

Washington D.C. - March 7, 1850.

|

Mr. President, |

I wish to speak

to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a

Northern man, but as an American, and a member

of the Senate of the United States. It is

fortunate that there is a Senate of the United

States; a body not yet moved from its propriety,

not lost to a just sense of its own dignity and

its own high responsibilities, and a body to

which the country looks, with confidence, for

wise, moderate, patriotic, and healing counsels.

It is not to be denied that we live in the midst

of strong agitations, and are surrounded by very

considerable dangers to our institutions and

government. The imprisoned winds are let loose.

The East, the North, and the stormy South

combine to throw the whole sea into commotion,

to toss its billows to the skies, and disclose

its profoundest depths. I do not affect to

regard myself, Mr. President, as holding, or as

fit to hold, the helm in this combat with the

political elements; but I have a duty to

perform, and I mean to perform it with fidelity,

not without a sense of existing dangers, but not

without hope. I have a part to act, not for my

own security or safety, for I am looking out for

no fragment upon which to float away from the

wreck, if wreck there must be, but for the good

of the whole, and the preservation of all; and

there is that which will keep me to my duty

during this struggle, whether the sun and the

stars shall appear, or shall not appear, for

many days. I speak to-day for the preservation

of the Union. "Hear me for my cause." I speak

to-day, out of a solicitous and anxious heart,

for the restoration to the country of that quiet

and that harmony which make the blessings of

this Union so rich, and so dear to us all. These

are the topics that I propose to myself to

discuss; these are the motives, and the sole

motives, that influence me in the wish to

communicate my opinions to the Senate and the

country; and if I can do any thing, however

little, for the promotion of these ends, I shall

have accomplished all that I expect.

Mr. President, it may not be amiss to recur very

briefly to the events which, equally sudden and

extraordinary, have brought the country into its

present political condition. In May, 1846, the

United States declared war against Mexico. Our

armies, then on the frontiers, entered the

provinces of that republic, met and defeated all

her troops, penetrated her mountain passes, and

occupied her capital. The marine force of the

United States took possession of her forts and

her towns, on the Atlantic and on the Pacific.

In less than two years a treaty was negotiated,

by which Mexico ceded to the United States a

vast territory, extending seven or eight hundred

miles along the shores of the Pacific, and

reaching back over the mountains, and across the

desert, until it joins the frontier of the State

of Texas. It so happened, in the distracted and

feeble condition of the Mexican government,

that, before the declaration of war by the

United States against Mexico had become known in

California, the people of California, under the

lead of American officers, overthrew the

existing Mexican provincial government, and

raised an independent flag. When the news

arrived at San Francisco that war had been

declared by the United States against Mexico,

this independent flag was pulled down, and the

stars and stripes of this Union hoisted in its

stead. So, Sir, before the war was over, the

forces of the United States, military and naval,

had possession of San Francisco and Upper

California, and a great rush of emigrants from

various parts of the world took place into

California in 1846 and 1847. But now behold

another wonder.

In January of 1848, a party of Mormons made a

discovery of an extraordinarily rich mine of

gold, or rather of a great quantity of gold,

hardly proper to be called a mine, for it was

spread near the surface, on the lower part of

the south, or American, branch of the

Sacramento. They attempted to conceal their

discovery for some time; but soon another

discovery of gold, perhaps of greater

importance, was made, on another part of the

American branch of the Sacramento, and near

Sutter's Fort, as it is called. The fame of

these discoveries spread far and wide. They

inflamed more and more the spirit of emigration

towards California, which had already been

excited; and adventurers crowded into the

country by hundreds, and flocked towards the Bay

of San Francisco. This, as I have said, took

place in the winter and spring of 1848. The

digging commenced in the spring of that year,

and from that time to this the work of searching

for gold has been prosecuted with a success not

heretofore known in the history of this globe.

You recollect, Sir, how incredulous at first the

American public was at the accounts which

reached us of these discoveries but we all know,

now, that these accounts received, and continue

to receive, daily confirmation, and down to the

present moment I suppose the assurance is as

strong, after the experience of these several

months, of the existence of deposits of gold

apparently inexhaustible in the regions near San

Francisco, in California, as it was at any

period of the earlier dates of the accounts.

It so happened, Sir, that although, after the

return of peace, it became a very important

subject for legislative consideration and

legislative decision to provide a proper

territorial government for California, yet

differences of opinion between the two houses of

Congress prevented the establishment of any such

territorial government at the last session.

Under this state of things, the inhabitants of

California, already amounting to a considerable

number, thought it to be their duty, in the

summer of last year, to establish a local

government. Under the proclamation of General

Riley, the people chose delegates to a

convention, and that convention met at Monterey.

It formed a constitution for the State of

California, which, being referred to the people,

was adopted by them in their primary

assemblages. Desirous of immediate connection

with the United States, its Senators were

appointed and Representatives chosen, who have

come hither, bringing with them the authentic

constitution of the State of California; and

they now present themselves, asking, in behalf

of their constituents, that it may be admitted

into this Union as one of the United States.

This constitution, Sir, contains an express

prohibition of slavery, or involuntary

servitude, in the State of California. It is

said, and I suppose truly, that, of the members

who composed that convention, some sixteen were

natives of, and had been residents in, the

slave-holding States, about twenty-two were from

the non-slaveholding States, and the remaining

ten members were either native Californians or

old settlers in that country. This prohibition

of slavery, it is said, was inserted with entire

unanimity.

It is this circumstance, Sir, the prohibition of

slavery, which has contributed to raise, I do

not say it has wholly raised, the dispute as to

the propriety of the admission of California

into the Union under this constitution. It is

not to be denied, Mr. President, nobody thinks

of denying, that, whatever reasons were assigned

at the commencement of the late war with Mexico,

it was prosecuted for the purpose of the

acquisition of territory, and under the alleged

argument that the cession of territory was the

only form in which proper compensation could be

obtained by the United States, from Mexico, for

the various claims and demands which the people

of this country had against that government. At

any rate, it will be found that President Polk's

message, at the commencement of the session of

December, 1847, avowed that the war was to be

prosecuted until some acquisition of territory

should be made. As the acquisition was to be

south of the line of the United States, in warm

climates and countries, it was naturally, I

suppose, expected by the South, that whatever

acquisitions were made in that region would be

added to the slave-holding portion of the United

States. Very little of accurate information was

possessed of the real physical character, either

of California or New Mexico, and events have not

turned out as was expected. Both California and

New Mexico are likely to come in as free States;

and therefore some degree of disappointment and

surprise has resulted. In other words, it is

obvious that the question which has so long

harassed the country, and at some times very

seriously alarmed the minds of wise and good

men, has come upon us for a fresh

discussion,—the question of slavery in these

United States.

Now, Sir, I propose, perhaps at the expense of

some detail and consequent detention of the

Senate, to review historically this question,

which, partly in consequence of its own

importance, and partly, perhaps mostly, in

consequence of the manner in which it has been

discussed in different portions of the country,

has been a source of so much alienation and

unkind feeling between them.

We all know, Sir, that slavery has existed in

the world from time immemorial. There was

slavery, in the earliest periods of history,

among the Oriental nations. There was slavery

among the Jews; the theocratic government of

that people issued no injunction against it.

There was slavery among the Greeks; and the

ingenious philosophy of the Greeks found, or

sought to find, a justification for it exactly

upon the grounds which have been assumed for

such a justification in this country; that is, a

natural and original difference among the races

of mankind, and the inferiority of the black or

colored race to the white. The Greeks justified

their system of slavery upon that idea,

precisely. They held the African and some of the

Asiatic tribes to be inferior to the white race;

but they did not show, I think, by any close

process of logic, that, if this were true, the

more intelligent and the stronger had therefore

a right to subjugate the weaker.

The more manly philosophy and jurisprudence of

the Romans placed the justification of slavery

on entirely different grounds. The Roman

jurists, from the first and down to the fall of

the empire, admitted that slavery was against

the natural law, by which, as they maintained,

all men, of whatsoever clime, color, or

capacity, were equal; but they justified

slavery, first, upon the ground and authority of

the law of nations, arguing, and arguing truly,

that at that day the conventional law of nations

admitted that captives in war, whose lives,

according to the notions of the times, were at

the absolute disposal of the captors, might, in

exchange for exemption from death, be made

slaves for life, and that such servitude might

descend to their posterity. The jurists of Rome

also maintained, that, by the civil law, there

might be servitude or slavery, personal and

hereditary; first, by the voluntary act of an

individual, who might sell himself into slavery;

secondly, by his being reduced into a state of

slavery by his creditors, in satisfaction of his

debts; and, thirdly, by being placed in a state

of servitude or slavery for crime. At the

introduction of Christianity, the Roman world

was full of slaves, and I suppose there is to be

found no injunction against that relation

between man and man in the teachings of the

Gospel of Jesus Christ or of any of his

Apostles. The object of the instruction imparted

to mankind by the Founder of Christianity was to

touch the heart, purify the soul, and improve

the lives of individual men. That object went

directly to the first fountain of all the

political and social relations of the human

race, as well as of all true religious feeling,

the individual heart and mind of man.

Now, Sir, upon the general nature and influence

of slavery there exists a wide difference of

opinion between the northern portion of this

country and the southern. It is said on the one

side, that, although not the subject of any

injunction or direct prohibition in the New

Testament, slavery is a wrong; that it is

founded merely in the right of the strongest;

and that it is an oppression, like unjust wars,

like all those conflicts by which a powerful

nation subjects a weaker to its will; and that,

in its nature, whatever may be said of it in the

modifications which have taken place, it is not

according to the meek spirit of the Gospel. It

is not "kindly affectioned"; it does not "seek

another's, and not its own"; it does not "let

the oppressed go free." These are sentiments

that are cherished, and of late with greatly

augmented force, among the people of the

Northern States. They have taken hold of the

religious sentiment of that part of the country,

as they have, more or less, taken hold of the

religious feelings of a considerable portion of

mankind. The South, upon the other side, having

been accustomed to this relation between the two

races all their lives, from their birth, having

been taught, in general, to treat the subjects

of this bondage with care and kindness, and I

believe, in general, feeling great kindness for

them, have not taken the view of the subject

which I have mentioned. There are thousands of

religious men, with consciences as tender as any

of their brethren at the North, who do not see

the unlawfulness of slavery; and there are more

thousands, perhaps, that, whatsoever they may

think of it in its origin, and as a matter

depending upon natural right, yet take things as

they are, and, finding slavery to be an

established relation of the society in which

they live, can see no way in which, let their

opinions on the abstract question be what they

may, it is in the power of the present

generation to relieve themselves from this

relation. And candor obliges me to say, that I

believe they are just as conscientious, many of

them, and the religious people, all of them, as

they are at the North who hold different

opinions.

The honorable Senator from South Carolina the

other day alluded to the separation of that

great religious community, the Methodist

Episcopal Church. That separation was brought

about by differences of opinion upon this

particular subject of slavery. I felt great

concern, as that dispute went on, about the

result. I was in hopes that the difference of

opinion might be adjusted, because I looked upon

that religious denomination as one of the great

props of religion and morals throughout the

whole country, from Maine to Georgia, and

westward to our utmost western boundary. The

result was against my wishes and against my

hopes. I have read all their proceedings and all

their arguments; but I have never yet been able

to come to the conclusion that there was any

real ground for that separation; in other words,

that any good could be produced by that

separation. I must say I think there was some

want of candor and charity. Sir, when a question

of this kind seizes on the religious sentiments

of mankind, and comes to be discussed in

religious assemblies of the clergy and laity,

there is always to be expected, or always to be

feared, a great degree of excitement. It is in

the nature of man, manifested by his whole

history, that religious disputes are apt to

become warm in proportion to the strength of the

convictions which men entertain of the magnitude

of the questions at issue. In all such disputes,

there will sometimes be found men with whom

every thing is absolute; absolutely wrong, or

absolutely right. They see the right clearly;

they think others ought so to see it, and they

are disposed to establish a broad line, of

distinction between what is right and what is

wrong. They are not seldom willing to establish

that line upon their own convictions of truth

and justice; and are ready to mark and guard it

by placing along it a series of dogmas, as lines

of boundary on the earth's surface are marked by

posts and stones. There are men who, with clear

perceptions, as they think, of their own duty,

do not see how too eager a pursuit of one duty

may involve them in the violation of others, or

how too warm an embracement of one truth may

lead to a disregard of other truths equally

important. As I heard it stated strongly, not

many days ago, these persons are disposed to

mount upon some particular duty, as upon a

war-horse, and to drive furiously on and upon

and over all other duties that may stand in the

way. There are men who, in reference to disputes

of that sort, are of opinion that human duties

may be ascertained with the exactness of

mathematics. They deal with morals as with

mathematics; and they think what is right may be

distinguished from what is wrong with the

precision of an algebraic equation. They have,

therefore, none too much charity towards others

who differ from them. They are apt, too, to

think that nothing is good but what is perfect,

and that there are no compromises or

modifications to be made in consideration of

difference of opinion or in deference to other

men's judgment. If their perspicacious vision

enables them to detect a spot on the face of the

sun, they think that a good reason why the sun

should be struck down from heaven. They prefer

the chance of running into utter darkness to

living in heavenly light, if that heavenly light

be not absolutely without any imperfection.

There are impatient men; too impatient always to

give heed to the admonition of St. Paul, that we

are not to "do evil that good may come"; too

impatient to wait for the slow progress of moral

causes in the improvement of mankind. They do

not remember that the doctrines and the miracles

of Jesus Christ have, in eighteen hundred years,

converted only a small portion of the human

race; and among the nations that are converted

to Christianity, they forget how many vices and

crimes, public and private, still prevail, and

that many of them, public crimes especially,

which are so clearly offences against the

Christian religion, pass without exciting

particular indignation. Thus wars are waged, and

unjust wars. I do not deny that there may be

just wars. There certainly are; but it was the

remark of an eminent person, not many years ago,

on the other side of the Atlantic, that it is

one of the greatest reproaches to human nature

that wars are sometimes just. The defence of

nations sometimes causes a just war against the

injustice of other nations. In this state of

sentiment upon the general nature of slavery

lies the cause of a great part of those unhappy

divisions, exasperations, and reproaches which

find vent and support in different parts of the

Union.

But we must view things as they are. Slavery

does exist in the United States. It did exist in

the States before the adoption of this

Constitution, and at that time. Let us,

therefore, consider for a moment what was the

state of sentiment, North and South, in regard

to slavery, at the time this Constitution was

adopted. A remarkable change has taken place

since; but what did the wise and great men of

all parts of the country think of slavery then?

In what estimation did they hold it at the time

when this Constitution was adopted? It will be

found, Sir, if we will carry ourselves by

historical research back to that day, and

ascertain men's opinions by authentic records

still existing among us, that there was then no

diversity of opinion between the North and the

South upon the subject of slavery. It will be

found that both parts of the country held it

equally an evil,—a moral and political evil. It

will not be found that, either at the North or

at the South, there was much, though there was

some, invective against slavery as inhuman and

cruel. The great ground of objection to it was

political; that it weakened the social fabric;

that, taking the place of free labor, society

became less strong and labor less productive;

and therefore we find from all the eminent men

of the time the clearest expression of their

opinion that slavery is an evil. They ascribed

its existence here, not without truth, and not

without some acerbity of temper and force of

language, to the injurious policy of the mother

country, who, to favor the navigator, had

entailed these evils upon the Colonies. I need

hardly refer, Sir, particularly to the

publications of the day. They are matters of

history on the record. The eminent men, the most

eminent men, and nearly all the conspicuous

politicians of the South, held the same

sentiments,—that slavery was an evil, a blight,

a scourge, and a curse. There are no terms of

reprobation of slavery so vehement in the North

at that day as in the South. The North was not

so much excited against it as the South; and the

reason is, I suppose, that there was much less

of it at the North, and the people did not see,

or think they saw, the evils so prominently as

they were seen, or thought to be seen, at the

South.

Then, Sir, when this Constitution was framed,

this was the light in which the Federal

Convention viewed it. That body reflected the

judgment and sentiments of the great men of the

South. A member of the other house, whom I have

not the honor to know, has, in a recent speech,

collected extracts from these public documents.

They prove the truth of what I am saying, and

the question then was, how to deal with it, and

how to deal with it as an evil. They came to

this general result. They thought that slavery

could not be continued in the country if the

importation of slaves were made to cease, and

therefore they provided that, after a certain

period, the importation might be prevented by

the act of the new government. The period of

twenty years was proposed by some gentleman from

the North, I think, and many members of the

Convention from the South opposed it as being

too long. Mr. Madison especially was somewhat

warm against it. He said it would bring too much

of this mischief into the country to allow the

importation of slaves for such a period. Because

we must take along with us, in the whole of this

discussion, when we are considering the

sentiments and opinions in which the

constitutional provision originated, that the

conviction of all men was, that, if the

importation of slaves ceased, the white race

would multiply faster than the black race, and

that slavery would therefore gradually wear out

and expire. It may not be improper here to

allude to that, I had almost said, celebrated

opinion of Mr. Madison. You observe, Sir, that

the term slave, or slavery, is not used in the

Constitution. The Constitution does not require

that "fugitive slaves" shall be delivered up. It

requires that persons held to service in one

State, and escaping into another, shall be

delivered up. Mr. Madison opposed the

introduction of the term slave, or slavery, into

the Constitution; for he said that he did not

wish to see it recognized by the Constitution of

the United States of America that there could be

property in men.

Now, Sir, all this took place in the Convention

in 1787; but connected with this, concurrent and

contemporaneous, is another important

transaction, not sufficiently attended to. The

Convention for framing this Constitution

assembled in Philadelphia in May, and sat until

September, 1787. During all that time the

Congress of the United States was in session at

New York. It was a matter of design, as we know,

that the Convention should not assemble in the

same city where Congress was holding its

sessions. Almost all the public men of the

country, therefore, of distinction and eminence,

were in one or the other of these two

assemblies; and I think it happened, in some

instances, that the same gentlemen were members

of both bodies. If I mistake not, such was the

case with Mr. Rufus King, then a member of

Congress from Massachusetts. Now, at the very

time when the Convention in Philadelphia was

framing this Constitution, the Congress in New

York was framing the Ordinance of 1787, for the

organization and government of the territory

northwest of the Ohio. They passed that

Ordinance on the 13th of July, 1787, at New

York, the very month, perhaps the very day, on

which these questions about the importation of

slaves and the character of slavery were debated

in the Convention at Philadelphia. So far as we

can now learn, there was a perfect concurrence

of opinion between these two bodies; and it

resulted in this Ordinance of 1787, excluding

slavery from all the territory over which the

Congress of the United States had jurisdiction,

and that was all the territory northwest of the

Ohio. Three years before, Virginia and other

States had made a cession of that great

territory to the United States; and a most

munificent act it was. I never reflect upon it

without a disposition to do honor and justice,

and justice would be the highest honor, to

Virginia, for the cession of her northwestern

territory. I will say, Sir, it is one of her

fairest claims to the respect and gratitude of

the country, and that, perhaps, it is only

second to that other claim which belongs to

her,—that from her counsels, and from the

intelligence and patriotism of her leading

statesmen, proceeded the first idea put into

practice of the formation of a general

constitution of the United States. The Ordinance

of 1787 applied to the whole territory over

which the Congress of the United States had

jurisdiction. It was adopted two years before

the Constitution of the United States went into

operation; because the Ordinance took effect

immediately on its passage, while the

Constitution of the United States, having been

framed, was to be sent to the States to be

adopted by their conventions; and then a

government was to be organized under it. This

Ordinance, then, was in operation and force when

the Constitution was adopted, and the government

put in motion, in April, 1789.

Mr. President, three things are quite clear as

historical truths. One is, that there was an

expectation that, on the ceasing of the

importation of slaves from Africa, slavery would

begin to run out here. That was hoped and

expected. Another is, that, as far as there was

any power in Congress to prevent the spread of

slavery in the United States, that power was

executed in the most absolute manner, and to the

fullest extent. An honorable member, whose

health does not allow him to be here to-day—

A SENATOR. He is here.

I am very happy to hear that he is; may he long

be here, and in the enjoyment of health to serve

his country! The honorable member said, the

other day, that he considered this Ordinance as

the first in the series of measures calculated

to enfeeble the South, and deprive them of their

just participation in the benefits and

privileges of this government. He says, very

properly, that it was enacted under the old

Confederation, and before this Constitution went

into effect; but my present purpose is only to

say, Mr. President, that it was established with

the entire and unanimous concurrence of the

whole South. Why, there it stands! The vote of

every State in the Union was unanimous in favor

of the Ordinance, with the exception of a single

individual vote, and that individual vote was

given by a Northern man. This Ordinance

prohibiting slavery for ever northwest of the

Ohio has the hand and seal of every Southern

member in Congress. It was therefore no

aggression of the North on the South. The other

and third clear historical truth is, that the

Convention meant to leave slavery in the States

as they found it, entirely under the authority

and control of the States themselves.

This was the state of things, Sir, and this the

state of opinion, under which those very

important matters were arranged, and those three

important things done; that is, the

establishment of the Constitution of the United

States with a recognition of slavery as it

existed in the States; the establishment of the

ordinance for the government of the Northwestern

Territory, prohibiting, to the full extent of

all territory owned by the United States, the

introduction of slavery into that territory,

while leaving to the States all power over

slavery in their own limits; and creating a

power, in the new government, to put an end to

the importation of slaves, after a limited

period. There was entire coincidence and

concurrence of sentiment between the North and

the South, upon all these questions, at the

period of the adoption of the Constitution. But

opinions, Sir, have changed, greatly changed;

changed North and changed South. Slavery is not

regarded in the South now as it was then. I see

an honorable member of this body paying me the

honor of listening to my remarks; he brings to

my mind, Sir, freshly and vividly, what I have

learned of his great ancestor, so much

distinguished in his day and generation, so

worthy to be succeeded by so worthy a grandson,

and of the sentiments he expressed in the

Convention in Philadelphia.

Here we may pause. There was, if not an entire

unanimity, a general concurrence of sentiment

running through the whole community, and

especially entertained by the eminent men of all

parts of the country. But soon a change began,

at the North and the South, and a difference of

opinion showed itself; the North growing much

more warm and strong against slavery, and the

South growing much more warm and strong in its

support. Sir, there is no generation of mankind

whose opinions are not subject to be influenced

by what appear to them to be their present

emergent and exigent interests. I impute to the

South no particularly selfish view in the change

which has come over her. I impute to her

certainly no dishonest view. All that has

happened has been natural. It has followed those

causes which always influence the human mind and

operate upon it. What, then, have been the

causes which have created so new a feeling in

favor of slavery in the South, which have

changed the whole nomenclature of the South on

that subject, so that, from being thought and

described in the terms I have mentioned and will

not repeat, it has now become an institution, a

cherished institution, in that quarter; no evil,

no scourge, but a great religious, social, and

moral blessing, as I think I have heard it

latterly spoken of? I suppose this, Sir, is

owing to the rapid growth and sudden extension

of the COTTON plantations of the South. So far

as any motive consistent with honor, justice,

and general judgment could act, it was the

COTTON interest that gave a new desire to

promote slavery, to spread it, and to use its

labor. I again say that this change was produced

by causes which must always produce like

effects. The whole interest of the South became

connected, more or less, with the extension of

slavery. If we look back to the history of the

commerce of this country in the early years of

this government, what were our exports? Cotton

was hardly, or but to a very limited extent,

known. In 1791 the first parcel of cotton of the

growth of the United States was exported, and

amounted only to 19,200 pounds. It has gone on

increasing rapidly, until the whole crop may

now, perhaps, in a season of great product and

high prices, amount to a hundred millions of

dollars. In the years I have mentioned, there

was more of wax, more of indigo, more of rice,

more of almost every article of export from the

South, than of cotton. When Mr. Jay negotiated

the  treaty of 1794 with England, it is evident

from the twelfth article of the treaty, which

was suspended by the Senate, that he did not

know that cotton was exported at all from the

United States.

treaty of 1794 with England, it is evident

from the twelfth article of the treaty, which

was suspended by the Senate, that he did not

know that cotton was exported at all from the

United States.

Well, Sir, we know what followed. The age of

cotton became the golden age of our Southern

brethren. It gratified their desire for

improvement and accumulation, at the same time

that it excited it. The desire grew by what it

fed upon, and there soon came to be an eagerness

for other territory, a new area or new areas for

the cultivation of the cotton crop; and measures

leading to this result were brought about

rapidly, one after another, under the lead of

Southern men at the head of the government, they

having a majority in both branches of Congress

to accomplish their ends. The honorable member

from South Carolina observed that there has been

a majority all along in favor of the North. If

that be true, Sir, the North has acted either

very liberally and kindly, or very weakly; for

they never exercised that majority efficiently

five times in the history of the government,

when a division or trial of strength arose.

Never. Whether they were outgeneraled, or

whether it was owing to other causes, I shall

not stop to consider; but no man acquainted with

the history of the Union can deny that the

general lead in the politics of the country, for

three fourths of the period that has elapsed

since the adoption of the Constitution, has been

a Southern lead.

In 1802, in pursuit of the idea of opening a new

cotton region, the United States obtained a

cession from Georgia of the whole of her western

territory, now embracing the rich and growing

States of Alabama and Mississippi. In 1803

Louisiana was purchased from France, out of

which the States of Louisiana, Arkansas, and

Missouri have been framed, as slave-holding

States. In 1819 the cession of Florida was made,

bringing in another region adapted to

cultivation by slaves. Sir, the honorable member

from South Carolina thought he saw in certain

operations of the government, such as the manner

of collecting the revenue, and the tendency of

measures calculated to promote emigration into

the country, what accounts for the more rapid

growth of the North than the South. He ascribes

that more rapid growth, not to the operation of

time, but to the system of government and

administration established under this

Constitution. That is matter of opinion. To a

certain extent it may be true; but it does seem

to me that, if any operation of the government

can be shown in any degree to have promoted the

population, and growth, and wealth of the North,

it is much more sure that there are sundry

important and distinct operations of the

government, about which no man can doubt,

tending to promote, and which absolutely have

promoted, the increase of the slave interest and

the slave territory of the South. It was not

time that brought in Louisiana; it was the act

of men. It was not time that brought in Florida;

it was the act of men. And lastly, Sir, to

complete those acts of legislation which have

contributed so much to enlarge the area of the

institution of slavery, Texas, great and vast

and illimitable Texas, was added to the Union as

a slave State in 1845; and that, Sir, pretty

much closed the whole chapter, and settled the

whole account.

That closed the whole chapter and settled the

whole account, because the annexation of Texas,

upon the conditions and under the guaranties

upon which she was admitted, did not leave

within the control of this government an acre of

land, capable of being cultivated by slave

labor, between this Capitol and the Rio Grande

or the Nueces, or whatever is the proper

boundary of Texas; not an acre. From that

moment, the whole country, from this place to

the western boundary of Texas, was fixed,

pledged, fastened, decided, to be slave

territory for ever, by the solemn guaranties of

law. And I now say, Sir, as the proposition upon

which I stand this day, and upon the truth and

firmness of which I intend to act until it is

overthrown, that there is not at this moment

within the United States, or any territory of

the United States, a single foot of land, the

character of which, in regard to its being free

territory or slave territory, is not fixed by

some law, and some irrepealable law, beyond the

power of the action of the government. Is it not

so with respect to Texas? It is most manifestly

so. The honorable member from South Carolina, at

the time of the admission of Texas, held an

important post in the executive department of

the government; he was Secretary of State.

Another eminent person of great activity and

adroitness in affairs, I mean the late Secretary

of the Treasury, was a conspicuous member of

this body, and took the lead in the business of

annexation, in co-operation with the Secretary

of State; and I must say that they did their

business faithfully and thoroughly; there was no

botch left in it. They rounded it off, and made

as close joiner-work as ever was exhibited.

Resolutions of annexation were brought into

Congress, fitly joined together, compact,

efficient, conclusive upon the great object

which they had in view, and those resolutions

passed.

Allow me to read a part of these resolutions. It

is the third clause of the second section of the

resolution of the 1st of March, 1845, for the

admission of Texas, which applies to this part

of the case. That clause is as follows:—

"New States, of convenient size, not exceeding

four in number, in addition to said State of

Texas, and having sufficient population, may

hereafter, by the consent of said State, he

formed out of the territory thereof, which shall

be entitled to admission under the provisions of

the Federal Constitution. And such States as may

be formed out of that portion of said territory

lying south of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes

north latitude, commonly known as the

Missouri

Compromise line, shall be admitted into the

Union with or without slavery, as the people of

each State asking admission may desire; and in

such State or States as shall be formed out of

said territory north of said Missouri Compromise

line, slavery or involuntary servitude (except

for crime) shall be prohibited."

Missouri

Compromise line, shall be admitted into the

Union with or without slavery, as the people of

each State asking admission may desire; and in

such State or States as shall be formed out of

said territory north of said Missouri Compromise

line, slavery or involuntary servitude (except

for crime) shall be prohibited."

Now what is here stipulated, enacted, and

secured? It is, that all Texas south of 36° 30',

which is nearly the whole of it, shall be

admitted into the Union as a slave State. It was

a slave State, and therefore came in as a slave

State; and the guaranty is, that new States

shall be made out of it, to the number of four,

in addition to the State then in existence and

admitted at that time by these resolutions, and

that such States as are formed out of that

portion of Texas lying south of 36° 30' may come

in as slave States. I know no form of

legislation which can strengthen this. I know no

mode of recognition that can add a tittle of

weight to it. I listened respectfully to the

resolutions of my honorable friend from

Tennessee. He proposed to recognize that

stipulation with Texas. But any additional

recognition would weaken the force of it;

because it stands here on the ground of a

contract, a thing done for a consideration. It

is a law founded on a contract with Texas, and

designed to carry that contract into effect. A

recognition now, founded not on any

consideration, or any contract, would not be so

strong as it now stands on the face of the

resolution. I know no way, I candidly confess,

in which this government, acting in good faith,

as I trust it always will, can relieve itself

from that stipulation and pledge, by any honest

course of legislation whatever. And therefore I

say again, that, so far as Texas is concerned,

in the whole of that State south of 36° 30',

which, I suppose, embraces all the territory

capable of slave cultivation, there is no land,

not an acre, the character of which is not

established by law; a law which cannot be

repealed without the violation of a contract,

and plain disregard of the public faith.

I hope, Sir, it is now apparent that my

proposition, so far as it respects Texas, has

been maintained, and that the provision in this

article is clear and absolute; and it has been

well suggested by my friend from Rhode Island,

that that part of Texas which lies north of 36°

30' of north latitude, and which may be formed

into free States, is dependent, in like manner,

upon the consent of Texas, herself a slave

State.

Now, Sir, how came this? How came it to pass

that within these walls, where it is said by the

honorable member from South Carolina that the

free States have always had a majority, this

resolution of annexation, such as I have

described it, obtained a majority in both houses

of Congress? Sir, it obtained that majority by

the great number of Northern votes added to the

entire Southern vote, or at least nearly the

whole of the Southern vote. The aggregate was

made up of Northern and Southern votes. In the

House of Representatives there were about eighty

Southern votes and about fifty Northern votes

for the admission of Texas. In the Senate the

vote for the admission of Texas was

twenty-seven, and twenty-five against it; and of

those twenty-seven votes, constituting the

majority, no less than thirteen came from the

free States, and four of them were from New

England. The whole of these thirteen Senators,

constituting within a fraction, you see, one

half of all the votes in this body for the

admission of this immeasurable extent of slave

territory, were sent here by free States.

Sir, there is not so remarkable a chapter in our

history of political events, political parties,

and political men as is afforded by this

admission of a new slave-holding territory, so

vast that a bird cannot fly over it in a week.

New England, as I have said, with some of her

own votes, supported this measure. Three fourths

of the votes of liberty-loving Connecticut were

given for it in the other house, and one half

here. There was one vote for it from Maine, but,

I am happy to say, not the vote of the honorable

member who addressed the Senate the day before

yesterday, and who was then a Representative

from Maine in the House of Representatives; but

there was one vote from Maine, ay, and there was

one vote for it from Massachusetts, given by a

gentleman then representing, and now living in,

the district in which the prevalence of Free

Soil sentiment for a couple of years or so has

defeated the choice of any member to represent

it in Congress. Sir, that body of Northern and

Eastern men who gave those votes at that time

are now seen taking upon themselves, in the

nomenclature of politics, the appellation of the

Northern Democracy. They undertook to wield the

destinies of this empire, if I may give that

name to a republic, and their policy was, and

they persisted in it, to bring into this country

and under this government all the territory they

could. They did it, in the case of Texas, under

pledges, absolute pledges, to the slave

interest, and they afterwards lent their aid in

bringing in these new conquests, to take their

chance for slavery or freedom. My honorable

friend from Georgia, in March, 1847, moved the

Senate to declare that the war ought not to be

prosecuted for the conquest of Territory, or for

the dismemberment of Mexico. The whole of the

Northern Democracy voted against it. He did not

get a vote from them. It suited the patriotic

and elevated sentiments of the Northern

Democracy to bring in a world from among the

mountains and valleys of California and New

Mexico, or any other part of Mexico, and then

quarrel about it; to bring it in, and then

endeavor to put upon it the saving grace of the

Wilmot Proviso. There were two eminent and

highly respectable gentlemen from the North and

East, then leading gentlemen in the Senate, (I

refer, and I do so with entire respect, for I

entertain for both of those gentlemen, in

general, high regard, to Mr. Dix of New York and

Mr. Niles of Connecticut,) who both voted for

the admission of Texas. They would not have that

vote any other way than as it stood; and they

would have it as it did stand. I speak of the

vote upon the annexation of Texas. Those two

gentlemen would have the resolution of

annexation just as it is, without amendment; and

they voted for it just as it is, and their eyes

were all open to its true character. The

honorable member from South Carolina who

addressed us the other day was then Secretary of

State. His correspondence with Mr. Murphy, the

Chargé d'Affaires of the United States in Texas,

had been published. That correspondence was all

before those gentlemen, and the Secretary had

the boldness and candor to avow in that

correspondence, that the great object sought by

the annexation of Texas was to strengthen the

slave interest of the South. Why, Sir, he said

so in so many words—

MR. CALHOUN. Will the honorable Senator permit

me to interrupt him for a moment?

Certainly.

MR. CALHOUN. I am very reluctant to interrupt

the honorable gentleman; but, upon a point of so

much importance, I deem it right to put myself

rectus in curia. I did not put it upon the

ground assumed by the Senator. I put it upon

this ground: that Great Britain had announced to

this country, in so many words, that her object

was to abolish slavery in Texas, and, through

Texas, to accomplish the abolition of slavery in

the United States and the world. The ground I

put it on was, that it would make an exposed

frontier, and, if Great Britain succeeded in her

object, it would be impossible that that

frontier could be secured against the

aggressions of the Abolitionists; and that this

government was bound, under the guaranties of

the Constitution, to protect us against such a

state of things.

That comes, I suppose, Sir, to exactly the same

thing. It was, that

Texas must be obtained for the security of the

slave interest of the

South.

MR. CALHOUN. Another view is very distinctly

given.

That was the object set forth in the

correspondence of a worthy gentleman not now

living, who preceded the honorable member from

South Carolina in the Department of State. There

repose on the files of the Department, as I have

occasion to know, strong letters from Mr. Upshur

to the United States Minister in England, and I

believe there are some to the same Minister from

the honorable Senator himself, asserting to this

effect the sentiments of this government;

namely, that Great Britain was expected not to

interfere to take Texas out of the hands of its

then existing government and make it a free

country. But my argument, my suggestion, is

this: that those gentlemen who composed the

Northern Democracy when Texas was brought into

the Union saw clearly that it was brought in as

a slave country, and brought in for the purpose

of being maintained as slave territory, to the

Greek Kalends. I rather think the honorable

gentleman who was then Secretary of State might,

in some of his correspondence with Mr. Murphy,

have suggested that it was not expedient to say

too much about this object, lest it should

create some alarm. At any rate, Mr. Murphy wrote

to him that England was anxious to get rid of

the constitution of Texas, because it was a

constitution establishing slavery; and that what

the United States had to do was to aid the

people of Texas in upholding their constitution;

but that nothing should be said which should

offend the fanatical men of the North. But, Sir,

the honorable member did avow this object

himself, openly, boldly, and manfully; he did

not disguise his conduct or his motives.

MR. CALHOUN. Never, never.

What he means he is very apt to say.

MR. CALHOUN. Always, always.

And I honor him for it.

This admission of Texas was in 1845. Then in

1847, flagrante bello between the United States

and Mexico, the proposition I have mentioned was

brought forward by my friend from Georgia, and

the Northern Democracy voted steadily against

it. Their remedy was to apply to the

acquisitions, after they should come in, the

Wilmot Proviso. What follows? These two

gentlemen, worthy and honorable and influential

men, (and if they had not been they could not

have carried the measure,) these two gentlemen,

members of this body, brought in Texas, and by

their votes they also prevented the passage of

the resolution of the honorable member from

Georgia, and then they went home and took the

lead in the Free Soil party. And there they

stand, Sir! They leave us here, bound in honor

and conscience by the resolutions of annexation;

they leave us here, to take the odium of

fulfilling the obligations in favor of slavery

which they voted us into, or else the greater

odium of violating those obligations, while they

are at home making capital and rousing speeches

for free soil and no slavery. And therefore I

say, Sir, that there is not a chapter in our

history, respecting public measures and public

men, more full of what would create surprise,

more full of what does create in my mind,

extreme mortification, than that of the conduct

of the Northern Democracy on this subject.

Mr. President, sometimes, when a man is found in

a new relation to things around him and to other

men, he says the world has changed, and that he

has not changed. I believe, Sir, that our

self-respect leads us often to make this

declaration in regard to ourselves when it is

not exactly true. An individual is more apt to

change, perhaps, than all the world around him.

But under the present circumstances, and under

the responsibility which I know I incur by what

I am now stating here, I feel at liberty to

recur to the various expressions and statements,

made at various times, of my own opinions and

resolutions respecting the admission of Texas,

and all that has followed. Sir, as early as

1836, or in the early part of 1837, there was

conversation and correspondence between myself

and some private friends on this project of

annexing Texas to the United States; and an

honorable gentleman with whom I have had a long

acquaintance, a friend of mine, now perhaps in

this chamber, I mean General Hamilton, of South

Carolina, was privy to that correspondence. I

had voted for the recognition of Texan

independence, because I believed it to be an

existing fact, surprising and astonishing as it

was, and I wished well to the new republic; but

I manifested from the first utter opposition to

bringing her, with her slave territory, into the

Union. I happened, in 1837, to make a public

address to political friends in New York, and I

then stated my sentiments upon the subject. It

was the first time that I had occasion to advert

to it; and I will ask a friend near me to have

the kindness to read an extract from the speech

made by me on that occasion. It was delivered in

Niblo's Saloon, in 1837.

Mr. Greene then read the following extract from

the speech of Mr.

Webster to which he referred:—

"Gentlemen, we all see that, by whomsoever

possessed, Texas is likely to be a slave-holding

country; and I frankly avow my entire

unwillingness to do any thing that shall extend

the slavery of the African race on this

continent, or add other slave-holding States to

the Union. When I say that I regard slavery in

itself as a great moral, social, and political

evil, I only use language which has been adopted

by distinguished men, themselves citizens of

slave-holding States. I shall do nothing,

therefore, to favor or encourage its further

extension. We have slavery already amongst us.

The Constitution found it in the Union; it

recognized it, and gave it solemn guaranties. To

the full extent of these guaranties we are all

bound, in honor, in justice, and by the

Constitution. All the stipulations contained in

the Constitution in favor of the slave-holding

States which are already in the Union ought to

be fulfilled, and, so far as depends on me,

shall be fulfilled, in the fullness of their

spirit, and to the exactness of their letter.

Slavery, as it exists in the States, is beyond

the reach of Congress. It is a concern of the

States themselves; they have never submitted it

to Congress, and Congress has no rightful power

over it. I shall concur, therefore, in no act,

no measure, no menace, no indication of purpose,

which shall interfere or threaten to interfere

with the exclusive authority of the several

States over the subject of slavery as it exists

within their respective limits. All this appears

to me to be matter of plain and imperative duty.

"But when we come to speak of admitting new

States, the subject assumes an entirely

different aspect. Our rights and our duties are

then both different….

"I see, therefore, no political necessity for

the annexation of Texas to the Union; no

advantages to be derived from it; and objections

to it of a strong, and, in my judgment, decisive

character."

I have nothing, Sir, to add to, or to take from,

those sentiments. That speech, the Senate will

perceive, was made in 1837. The purpose of

immediately annexing Texas at that time was

abandoned or postponed; and it was not revived

with any vigor for some years. In the mean time

it happened that I had become a member of the

executive administration, and was for a short

period in the Department of State. The

annexation of Texas was a subject of

conversation, not confidential, with the

President and heads of departments, as well as

with other public men. No serious attempt was

then made, however, to bring it about. I left

the Department of State in May, 1843, and

shortly after I learned, though by means which

were no way connected with official information,

that a design had been taken up of bringing

Texas, with her slave territory and population,

into this Union. I was in Washington at the

time, and persons are now here who will remember

that we had an arranged meeting for conversation

upon it. I went home to Massachusetts and

proclaimed the existence of that purpose, but I

could get no audience and but little attention.

Some did not believe it, and some were too much

engaged in their own pursuits to give it any

heed. They had gone to their farms or to their

merchandise, and it was impossible to arouse any

feeling in New England, or in Massachusetts,

that should combine the two great political

parties against this annexation; and, indeed,

there was no hope of bringing the Northern

Democracy into that view, for their leaning was

all the other way. But, Sir, even with Whigs,

and leading Whigs, I am ashamed to say, there

was a great indifference towards the admission

of Texas, with slave territory, into this Union.

The project went on. I was then out of Congress.

The annexation resolutions passed on the 1st of

March, 1845; the legislature of Texas complied

with the conditions and accepted the guaranties;

for the language of the resolution is, that

Texas is to come in "upon the conditions and

under the guaranties herein prescribed." I was

returned to the Senate in March, 1845, and was

here in December following, when the acceptance

by Texas of the conditions proposed by Congress

was communicated to us by the President, and an

act for the consummation of the union was laid

before the two houses. The connection was then

not completed. A final law, doing the deed of

annexation ultimately, had not been passed; and

when it was put upon its final passage here, I

expressed my opposition to it, and recorded my

vote in the negative; and there that vote

stands, with the observations that I made upon

that occasion. Nor is this the only occasion on

which I have expressed myself to the same

effect. It has happened that, between 1837 and

this time, on various occasions, I have

expressed my entire opposition to the admission

of slave States, or the acquisition of new slave

territories, to be added to the United States. I

know, Sir, no change in my own sentiments, or my

own purposes, in that respect. I will now ask my

friend from Rhode Island to read another extract

from a speech of mine made at a Whig Convention

in Springfield, Massachusetts, in the month of

September, 1847.

Mr. Greene here read the following extract:—

"We hear much just now of a panacea for the

dangers and evils of slavery and slave

annexation, which they call the 'Wilmot

Proviso.' That certainly is a just sentiment,

but it is not a sentiment to found any new party

upon. It is not a sentiment on which

Massachusetts Whigs differ. There is not a man

in this hall who holds to it more firmly than I

do, nor one who adheres to it more than another.

"I feel some little interest in this matter,

Sir. Did not I commit myself in 1837 to the

whole doctrine, fully, entirely? And I must be

permitted to say that I cannot quite consent

that more recent discoverers should claim the

merit and take out a patent.

"I deny the priority of their invention. Allow

me to say, Sir, it

is not their thunder….

"We are to use the first and the last and every

occasion which

offers to oppose the extension of slave power.

"But I speak of it here, as in Congress, as a

political question, a question for statesmen to

act upon. We must so regard it. I certainly do

not mean to say that it is less important in a

moral point of view, that it is not more

important in many other points of view; but as a

legislator, or in any official capacity, I must

look at it, consider it, and decide it as a

matter of political action."

On other occasions, in debates here, I have

expressed my determination to vote for no

acquisition, cession, or annexation, north or

south, east or west. My opinion has been, that

we have territory enough, and that we should

follow the Spartan maxim, "Improve, adorn what

you have," seek no further. I think that it was

in some observations that I made on the

three-million loan bill that I avowed this

sentiment. In short, Sir, it has been avowed

quite as often, in as many places, and before as

many assemblies, as any humble opinions of mine

ought to be avowed.

But now that, under certain conditions, Texas is

in the Union, with all her territory, as a slave

State, with a solemn pledge, also, that, if she

shall be divided into many States, those States

may come in as slave States south of 36° 30',

how are we to deal with this subject? I know no

way of honest legislation, when the proper time

comes for the enactment, but to carry into

effect all that we have stipulated to do. I do

not entirely agree with my honorable friend from

Tennessee, that, as soon as the time comes when

she is entitled to another representative, we

should create a new State. On former occasions,

in creating new States out of territories, we

have generally gone upon the idea that, when the

population of the territory amounts to about

sixty thousand, we would consent to its

admission as a State. But it is quite a

different thing when a State is divided, and two

or more States made out of it. It does not

follow in such a case that the same rule of

apportionment should be applied. That, however,

is a matter for the consideration of Congress,

when the proper time arrives. I may not then be

here; I may have no vote to give on the

occasion; but I wish it to be distinctly

understood, that, according to my view of the

matter, this government is solemnly pledged, by

law and contract, to create new States out of

Texas, with her consent, when her population

shall justify and call for such a proceeding,

and, so far as such States are formed out of

Texan territory lying south of 36° 30', to let

them come in as slave States. That is the

meaning of the contract which our friends, the

Northern Democracy, have left us to fulfill; and

I, for one, mean to fulfill it, because I will

not violate the faith of the government. What I

mean to say is, that the time for the admission

of new States formed out of Texas, the number of

such States, their boundaries, the requisite

amount of population, and all other things

connected with the admission, are in the free

discretion of Congress, except this; to wit,

that, when new States formed out of Texas are to

be admitted, they have a right, by legal

stipulation and contract, to come in as slave

States.

Now, as to California and New Mexico, I hold

slavery to be excluded from those territories by

a law even superior to that which admits and

sanctions it in Texas. I mean the law of nature,

of physical geography, the law of the formation

of the earth. That law settles for ever, with a

strength beyond all terms of human enactment,

that slavery cannot exist in California or New

Mexico. Understand me, Sir; I mean slavery as we

regard it; the slavery of the colored race as it

exists in the Southern States. I shall not

discuss the point, but leave it to the learned

gentlemen who have undertaken to discuss it; but

I suppose there is no slavery of that

description in California now. I understand that

peonism, a sort of penal servitude, exists

there, or rather a sort of voluntary sale of a

man and his offspring for debt; an arrangement

of a peculiar nature known to the law of Mexico.

But what I mean to say is, that it is as

impossible that African slavery, as we see it

among us, should find its way, or be introduced,

into California and New Mexico, as any other

natural impossibility. California and New Mexico

are Asiatic in their formation and scenery. They

are composed of vast ridges of mountains, of

great height, with broken ridges and deep

valleys. The sides of these mountains are

entirely barren; their tops capped by perennial

snow. There may be in California, now made free

by its constitution, and no doubt there are,

some tracts of valuable land. But it is not so

in New Mexico. Pray, what is the evidence which

every gentleman must have obtained on this

subject, from information sought by himself or

communicated by others? I have inquired and read

all I could find, in order to acquire

information on this important subject. What is

there in New Mexico that could, by any

possibility, induce anybody to go there with

slaves? There are some narrow strips of tillable

land on the borders of the rivers; but the

rivers themselves dry up before midsummer is

gone. All that the people can do in that region

is to raise some little articles, some little

wheat for their tortillas, and that by

irrigation. And who expects to see a hundred

black men cultivating tobacco, corn, cotton,

rice, or any thing else, on lands in New Mexico,

made fertile only by irrigation?

I look upon it, therefore, as a fixed fact, to

use the current expression of the day, that both

California and New Mexico are destined to be

free, so far as they are settled at all, which I

believe, in regard to New Mexico, will be but

partially for a great length of time; free by

the arrangement of things ordained by the Power

above us. I have therefore to say, in this

respect also, that this country is fixed for

freedom, to as many persons as shall ever live

in it, by a less repealable law than that which

attaches to the right of holding slaves in

Texas; and I will say further, that, if a

resolution or a bill were now before us, to

provide a territorial government for New Mexico,

I would not vote to put any prohibition into it

whatever. Such a prohibition would be idle, as

it respects any effect it would have upon the

territory; and I would not take pains uselessly

to reaffirm an ordinance of nature, nor to

re-enact the will of God. I would put in no

Wilmot Proviso for the mere purpose of a taunt

or a reproach. I would put into it no evidence

of the votes of superior power, exercised for no

purpose but to wound the pride, whether a just

and a rational pride, or an irrational pride, of

the citizens of the Southern States. I have no

such object, no such purpose. They would think

it a taunt, an indignity; they would think it to

be an act taking away from them what they regard

as a proper equality of privilege. Whether they

expect to realize any benefit from it or not,

they would think it at least a plain theoretic

wrong; that something more or less derogatory to

their character and their rights had taken

place. I propose to inflict no such wound upon

anybody, unless something essentially important

to the country, and efficient to the

preservation of liberty and freedom, is to be

effected. I repeat, therefore, Sir, and, as I do

not propose to address the Senate often on this

subject, I repeat it because I wish it to be

distinctly understood, that, for the reasons

stated, if a proposition were now here to

establish a government for New Mexico, and it

was moved to insert a provision for a

prohibition of slavery, I would not vote for it.

Sir, if we were now making a government for New

Mexico, and anybody should propose a Wilmot

Proviso, I should treat it exactly as Mr. Polk

treated that provision for excluding slavery

from Oregon. Mr. Polk was known to be in opinion

decidedly averse to the Wilmot Proviso; but he

felt the necessity of establishing a government

for the Territory of Oregon. The proviso was in

the bill, but he knew it would be entirely

nugatory; and, since it must be entirely

nugatory, since it took away no right, no

describable, no tangible, no appreciable right

of the South, he said he would sign the bill for

the sake of enacting a law to form a government

in that Territory, and let that entirely

useless, and, in that connection, entirely

senseless, proviso remain. Sir, we hear

occasionally of the annexation of Canada; and if

there be any man, any of the Northern Democracy,

or any one of the Free Soil party, who supposes

it necessary to insert a Wilmot Proviso in a

territorial government for New Mexico, that man

would of course be of opinion that it is

necessary to protect the everlasting snows of

Canada from the foot of slavery by the same

overspreading wing of an act of Congress. Sir,

wherever there is a substantive good to be done,

wherever there is a foot of land to be prevented

from becoming slave territory, I am ready to

assert the principle of the exclusion of

slavery. I am pledged to it from the year 1837;

I have been pledged to it again and again; and I

will perform those pledges; but I will not do a

thing unnecessarily that wounds the feelings of

others, or that does discredit to my own

understanding.

Now, Mr. President, I have established, so far

as I proposed to do so, the proposition with

which I set out, and upon which I intend to

stand or fall; and that is, that the whole

territory within the former United States, or in

the newly acquired Mexican provinces, has a

fixed and settled character, now fixed and

settled by law which cannot be repealed,—in the

case of Texas without a violation of public

faith, and by no human power in regard to

California or New Mexico; that, therefore, under

one or other of these laws, every foot of land

in the States or in the Territories has already

received a fixed and decided character.

Mr. President, in the excited times in which we

live, there is found to exist a state of

crimination and recrimination between the North

and South. There are lists of grievances

produced by each, and those grievances, real or

supposed, alienate the minds of one portion of

the country from the other, exasperate the

feelings, and subdue the sense of fraternal

affection, patriotic love, and mutual regard. I

shall bestow a little attention, Sir, upon these

various grievances existing on the one side and

on the other. I begin with complaints of the

South. I will not answer, further than I have,

the general statements of the honorable Senator

from South Carolina, that the North has

prospered at the expense of the South in

consequence of the manner of administering this

government, in the collecting of its revenues,

and so forth. These are disputed topics, and I

have no inclination to enter into them. But I

will allude to other complaints of the South,

and especially to one which has in my opinion

just foundation; and that is, that there has

been found at the North, among individuals and

among legislators, a disinclination to perform

fully their constitutional duties in regard to

the return of persons bound to service who have

escaped into the free States. In that respect,

the South, in my judgment, is right, and the

North is wrong. Every member of every Northern

legislature is bound by oath, like every other

officer in the country, to support the

Constitution of the United States; and the

article of the Constitution which says to these

States that they shall deliver up fugitives from

service is as binding in honor and conscience as

any other article. No man fulfils his duty in

any legislature who sets himself to find

excuses, evasions, escapes from this

constitutional obligation. I have always thought

that the Constitution addressed itself to the

legislatures of the States or to the States

themselves. It says that those persons escaping

to other States "shall be delivered up," and I

confess I have always been of the opinion that

it was an injunction upon the States themselves.

When it is said that a person escaping into

another State, and coming therefore within the

jurisdiction of that State, shall be delivered

up, it seems to me the import of the clause is,

that the State itself, in obedience to the

Constitution, shall cause him to be delivered

up. That is my judgment. I have always

entertained that opinion, and I entertain it

now. But when the subject, some years ago, was

before the Supreme Court of the United States,

the majority of the judges held that the power

to cause fugitives from service to be delivered

up was a power to be exercised under the

authority of this government. I do not know, on

the whole, that it may not have been a fortunate

decision. My habit is to respect the result of

judicial deliberations and the solemnity of

judicial decisions. As it now stands, the

business of seeing that these fugitives are

delivered up resides in the power of Congress

and the national judicature, and my friend at

the head of the Judiciary Committee has a bill

on the subject now before the Senate, which,

with some amendments to it, I propose to